I’ve written a couple of posts about ways in which Peter Jackson stumbles in his treatment of Tolkien. Basically, these criticisms come down to volume; Jackson tends to want to turn it all the way up all the time. Tokien’s a pretty slow-going — or, if you’d prefer, boring — writer in a lot of ways, and the slowness and the boringness is central not just to the form and experience of the novels, but to their themes. Tokien is someone who, like the Ents, wants to sit back in some wooded glade and tell you the names of everything. He likes being slow, he likes being boring — which is to say, there’s a lot of room in his adventure novels for the appreciation of the joys of having nothing in particular happen. The way his narrative continually stalls out is central to the novels’ rejection of violence — a rejection which is ambivalent, but in many ways determinative. Jackson can understand and rejoice in Tolkien’s battle scenes (as Tolkien does himself) but not in Tolkien’s various numerous nothing scenes. The films, therefore, are garish and loud and busy all through, embracing Tokien’s flash and fire and drama, but not his long, slow, Treebeard-like pauses.

There are a couple of instances, though, where I think Jackson’s version is better than Tokien’s. One of the most noticeable of these is in the character of Boromir.

In the Fellowship of the Ring (which I’ve just about finished reading to my son), Boromir — like most characters in the novel, with the exception of Frodo and perhaps Sam and Bilbo — is not given a whole lot in the way of subtle characterization. We learn that he is very strong and proud, and also that he’s strong and not especially trusting, nor, perhaps, trustworthy. He helps the company by plowing through snow with his body when they’re trapped on the mountain. He disagrees with Gandalf and Aragorn about the path the company should take. He boasts about Minas Tirith and the strength of men. And that’s kind of it. He doesn’t become friends with any of the company. For that matter, he doesn’t become friends with the reader. He’s a mighty, proud man, off there being mighty and proud, and then he tries to take the ring from Frodo like a dickhead, and then he dies mightily and proudly in battle. And overall it’s just hard to care that much.

The film, though, is quite different. In part, this is Sean Bean’s doing; he’s an incredibly charismatic actor, and he gives Boromir a jaunty, frat-boy, devil-may-care charm for which the book offers no textual warrant at all. But the writers, who commit many an atrocity to Tokien’s text, here also surpass him. There’s a wonderful scene where Boromir is teaching Merry and Pippin and (I think) Sam to swordfight in which they all end up together laughing and rolling on the ground. And there’s also a scene after they’ve left Moria, where the Hobbits are grieving for Gandalf’s death, where Boromir begs Aragon to give them a minute to recover themselves. In the books, his questioning of the leadership is almost always based on ignorance, or stubbornness; here, instead, it’s based on sympathy and care for his companions.

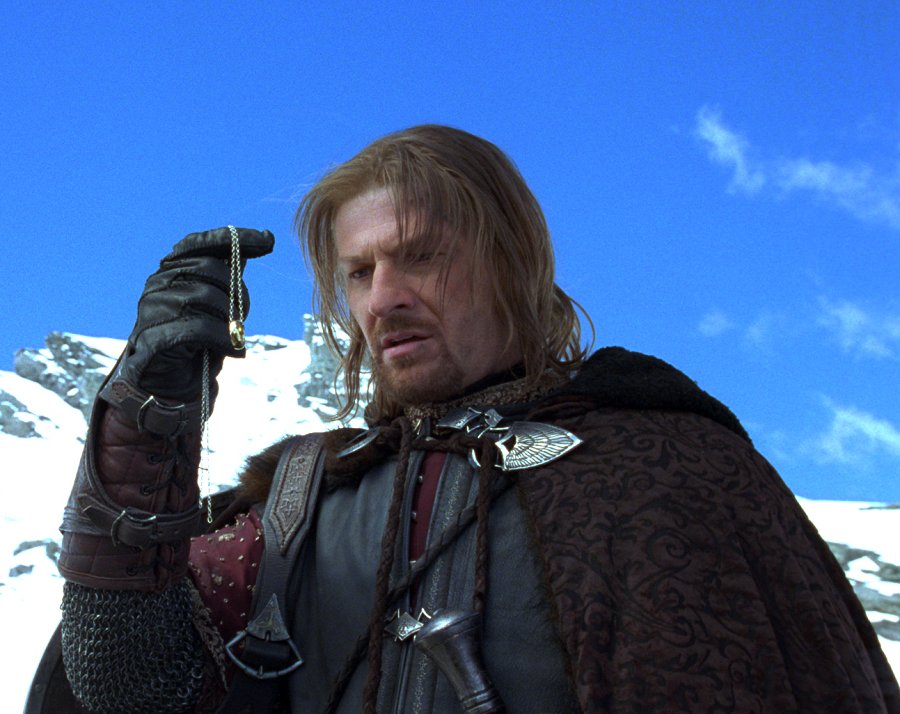

There are other little moments too. The writers split up Boromir’s speech at the end of the book; part of it, where he speaks of the ring as a little thing, and wonders why it holds such power over them, is delivered on the journey. The ring has come loose, and Boromir picks it up by its chain and gazes at it and addresses it, before handing it back to Frodo, cheerfully declaring “I care not!” as he ruffles Frodo’s hair. That “I care not,” in Tolkien (uttered when Frodo won’t show him the ring) comes across as sinister; a man trying to deceive. Sean Bean’s reading, though, sounds more like a man trying to deceive himself without even knowing he’s trying to deceive himself.

The earlier moment with the ring also makes it more responsible for Boromir’s corruption; it’s almost like it’s gunning for him. And the scene where he tries to take it from Frodo…again, in the book, Boromir was never all that pleasant to begin with, so it’s just an intensification of his unpleasantness. In the film, though, Bean manages to show Boromir’s corruption as the flip side of his virtues; his boisterous courage turned into aggression; his mercurial good cheer turned into petulance. It’s a virtuoso performance of a good man doing wrong.

The script also adds a level to Boromir’s character that is almost completely absent in the book; his relationship with Aragorn. In the book, the two men are mostly in sync; Boromir wants to go to Minas Tirith to aid the city, and Aragorn (as the returned king) plans to join him (though after Gandalf falls he worries he should go with Frodo instead). In the film, though (thanks no doubt to Peter Jackson’s need for more and more drama) Aragorn is deeply mistrustful of men (including himself), and wants nothing to do with the kingship. Boromir is at first resentful of Aragorn’s position (which will displace his father’s line of stewards), and angry at Aragon’s mistrust. But as he grows to know Aragorn, he changes — and as Aragorn grows to know Boromir, he changes too, drawing faith in men and rekindling his love of Minas Tirith from Boromir’s faith and love. At Boromir’s death, Aragorn vows, for the first time, to defend Minas Tirith — and Boromir, for the first time, pledges his loyalty. “I will not let our city fail,” Aragorn says, and Boromir repeats it with a kind of desperate satisfaction. “Our city…our city!” His final words — “I would have followed you, my brother; my captain; my king” — are, then, in many ways, the conclusion of a love story — a bittersweet consummation, with Boromir finally embracing the future he will never see. The scene always makes me cry…as opposed to his final words in the novel the Two Towers (“Farewell, Aragorn! Go to Minas Tirith and save my people! I have failed.”) which pretty much just makes me shrug.

It’s interesting, perhaps, that not only is the Boromir arc one of the few things that I think Jackson unequivocally did better than Tolkien, but it’s also one of the best things in the films, period. Jackson’s twitchiness and Hollywood instincts — his need to give Boromir something to do, his need to make a star appealing — get filtered through Sean Bean’s considerable skills and end up turning a dour nonentity into a nuanced character. If for Tolkien and more complicatedly for Jackson, Boromir’s strength turns to weakness, it’s nice to see Jackson, in this instance, turn his weaknesses to strengths.

Boromir’s death in the movie always makes me cry.

I’ve always thought the ring was after him, particularly. Not just because he was a man, but because he’d been so close to the power of the ring/Sauron for so long.

The other thing that the movie gets right, I think, is showing how Boromir and his people have been fighting Sauron, alone, for ages. Aragorn’s been hangin’ with the elves and doing his own thing, but Boromir’s been stuck in a city on the edge–keeping that power away from overrunning everyone. When he says, ‘You don’t just walk into Mordor,’ he’s right. Boromir and his people have been keeping the shire safe from even having to think about this stuff–but it’s come at a heavy cost, and they’re exhausted. I think Bean does a great job showing both the strength and the flickers of weakness. The strength, I think, wouldn’t mean as much without those flickers–even wonderfully strong loyal Boromir was tempted, so anyone of us could be tempted/corrupted. That’s why Frodo’s special.

Yeah…I think Bean is good at showing not only that Boromir is strong, but that he’s a good person in a lot of ways. The book definitely shows his physical strength and bravery, but doesn’t really make much effort to make him sympathetic in any other way….

Mostly I haven’t felt I had any business commenting on your Lord of the Rings posts, because I never liked Tolkien’s novels (in fact, they once led me to openly reject any book in which a map was required for comprehension–somehow as a twelve-year-old, I determined that a map was the ultimate red flag). Peter Jackson, whatever evil he may have done to the source material, stunned me by making something I genuinely enjoyed out of them (and I’ve even lifted my boycott on maps). But today, at least, I can pipe up and say, “I agree!” I actually think this more nuanced characterization of Boromir makes Faramir work better as well, but that might just be the book-hater talking.

I’ve been reading the books aloud to my son, which is…maybe not ideal in every way? The long lists of place names and such, which I’d just skip over if I was reading them to myself, end up being completely ridiculous when read aloud. I think my son finds them kind of funny, at least….

I really disliked the revamp of Faramir. In the book he’s buddies with Gandalf and knows about the ring and knows he can’t take it. Which I like as a characterization in itself…but also it makes sense of why his dad doesn’t like him. In the film, it’s just random…and the will he/won’t he take the ring seems rushed and unmotivated too…

The other thing I think the film does better than the book is the Eowyn arc, which I think is really beautifully done. (It’s true that I’ve kind of got a crush on Miranda Otto…but I’m pretty sure the crush is because I love her performance so much, rather than the other way around.)

Admittedly, I haven’t read the books since I was young, and my perspective might be quite different as an adult. But I remember thinking at the time that Faramir was too noble to be interesting, whereas I found him very interesting in the film. But even the films I haven’t watched in several years now, so I can’t honestly make a strong argument as to why. If I find a few hours to rewatch the last couple of films, perhaps I’ll come back and defend my opinion with more verve.

really very nice piece, Noah.

Yeah, I left the films thinking “poor Boromir, he kind of gets shafted by fate”, and his death is poignantly played. Which I didn’t feel after the books, where he is indeed a blank. Credit where it’s due — Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens co-wrote the screenplay, so we can’t put it down to Jackson and Bean alone.

Part of the reason for giving Boromir a richer and more sympathetic characterisation is the films’ tendency to play up the quasi-Shakespearean stuff — in this instance, the tragic hero undone by himself. There’s some stuff in the second one that reminded me of Shakespeare in a way that I can’t quite put my finger on, and probably couldn’t textually justify by reference to any of the plays…there’s a scene where Theoden is looking over a bunch of graves and waxing elegaic? And his stirring speeches before battle are obviously very Henry V.

I think the point about drama is definitely right, even if it’s hard to tell if it’s Shakespeare specifically…they’re just always looking to make it more theatrical, which in this case works very well, though sometimes not as much.

And right you are about Walsh and Boyens; they definitely deserve credit.

Beautifully written; perceptive and nicely nuanced, Noah. Bits such as “Sean Bean’s reading, though, sounds more like a man trying to deceive himself without even knowing he’s trying to deceive himself” are outstandingly on-target.

I find Jackson’s pumping-up of the drama and conflict in LOTR enjoyable and thoroughly defensible. Would audiences have sat through three 3-hour movies if the tone was “being slow…being boring…of the joys of having nothing in particular happen”?

But more subtle, rich emotional complexity, such as your superb exploration of the nuances added to Boromir, are indeed worth saluting.

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

The other thing I think the film does better than the book is the Eowyn arc, which I think is really beautifully done. (It’s true that I’ve kind of got a crush on Miranda Otto…but I’m pretty sure the crush is because I love her performance so much, rather than the other way around.)

———————–

Yes, it’s a wonderful performance; the fear showing in her eyes through that helmet, the valor she still summons to slay the Fell Beast and its rider. And when her dying father recognizes his daughter as the one who saved him from being ignobly devoured, and lovingly addresses her…I’m crying right now thinking about it! (And yes, the death of Boromir wrought tears too.)

Kudos also to the cinematic creative team for their strengthening of female characters such as Liv Tyler’s Arwen. In the film, she thrillingly casts this spell: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VlEhEw52kBg . In the book, “the water, enchanted by Elrond and Gandalf, formed a great wave and swept the Nine away, killing their horses…” ( http://lotr.wikia.com/wiki/Nazg%C3%BBl )

————————-

Melinda Beasi says:

…Tolkien’s novels…once led me to openly reject any book in which a map was required for comprehension–somehow as a twelve-year-old, I determined that a map was the ultimate red flag…

—————————

Yeah, those maps (all-too-frequent in Tolkien’s far lesser imitators) are a warning-signal. But, whether they’re maps to some tiresomely derivative fantasy world, or the locations of the murder suspects in Lord Plushmore’s mansion, I always just ignore them…