The Frenchman Albert Uderzo attained international fame as the cartoonist half of the team that produced one of the most successful comics characters of all time: Asterix the Gaul. Prior to drawing Asterix, however, Uderzo had spent some 15 years drawing other characters — most of whom are presented in this montage:

Wait a minute… up there in the right-hand corner…that blue-clad superhero looks suspiciously like an American character, Captain Marvel Jr., as published by Fawcett Comics in the U.S.A.

What gives?

It seems that in 1950, the Belgian comics weekly Bravo (fl.1936 — 1950) licensed Captain Marvel Jr. and decided to create its own stories:

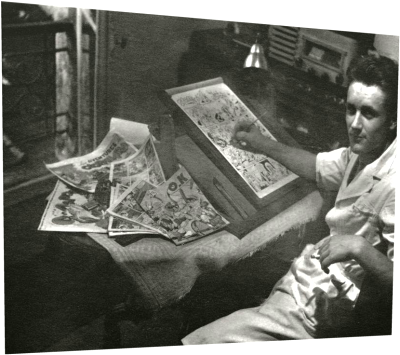

The serial ran for sixteen issues and was seen no more. Here’s some of Uderzo’s original art:

Young Albert Uderzo

Bravo was also responsible for another odd artistic pairing.

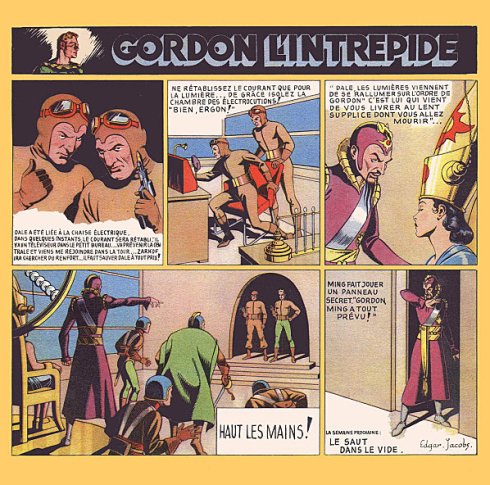

In 1942, Bravo was serialising the famed comic strip creation of Alex Raymond (1909–1956), Flash Gordon. Belgium was then under Nazi Germany’s occupation; so when Germany declared war on the United States in 1941, the supply of strips from the U.S.A. dried up completely. This was awkward, as Bravo was right in the middle of a storyline. So Bravo commissioned another artist to finish the story, and five final episodes were written and drawn — after which, the occupiers banned all American comics outright. A sample of this ersatz Flash:

Nazis and Fascists had an ambiguous relationship to American pop culture. On the one hand, they officially loathed it for its cosmopolitanism, its supposed degeneracy.

Typical is this German poster attacking degenerate (‘entartete) music, i.e. jazz; note the Star of David on the stereotyped Negro’s lapel:

And yet…the German army, the Wehrmacht, had its own official touring jazz bands! American pop culture continued to be prized, and the authorities had to make uneasy compromises.

For instance, Mussolini’s Fascist government once banned the Popeye comic strip. but the popular uproar of protestation was so intense that soon the adventures of “Braccio di Ferro” returned to Italian newspapers.

And Hitler’s favorite movie, reportedly, was Disney’s Snow White, of which he owned a personal print. Indeed, the popularity of Mickey Mouse and company was so great in Germany that Nazi propaganda circulated the notion that Walt Disney wasn’t American, but Spanish!

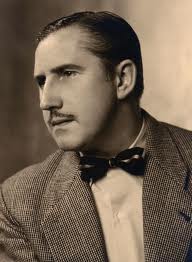

To return to that faux Flash Gordon: the author? Edgar P. Jacobs (1904–1987).

Edgar P. Jacobs

Jacobs was the creator of another tremendously successful and influential comic, after the war: Blake and Mortimer.

The blanket Nazi ban on American strips turned out to be a boon for Jacobs, as he was asked to replace Flash Gordon with an original science-fiction strip; the result was the highly imaginative Le Rayon U, a major step in his development as a cartoonist.

from ‘Le Rayon U’

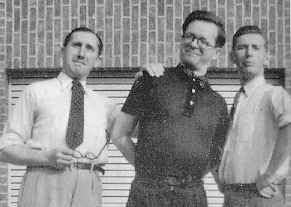

Jacobs was also key in “re-looking” Tintin, the famed creation of George‘Hergé’ Remi (1907–1983) — and the war was largely responsible for that, as well.

One effect on comics of the war was an acute paper shortage. Herge’s publisher, Casterman, informed him that it could no longer print his usual 100-plus page albums; henceforth they were to be limited to 62 story pages; to compensate, they would switch from black-and-white to color. This set a standard format for French and Belgian comics albums that endures until today.

Jacobs standardised the pastel color schemes typical of Tintin and other “clear line” comics; he also extensively redrew the older albums for the new format. His influence on the look of Tintin is second only to Hergé’s.

Edgar P. Jacobs, Jacques van Melkebeke, and Hergé in 1944. Van Melkebeke was Herge’s editor during the Occupation, and served time for collaboration.

I hope to post on occasion other oddities of artist/subject matchups… and would be grateful for any suggestions!

This is an enjoyable and informative article, Alex. It’s encouraging to see even the small advances (like color comics in Belgium and France) that can come from tragic events. But Hitler’s favorite film being Snow White is so perfect it’s funny.

Yes it is, isn’t it, John? A celebration of German volk lore.

Incidentally to this…my niece Elizabeth watched a DVD of “Snow White” when she was 4 years old, and in the sequence where Snow flees the Hunter through a malevolent forest she was badly frightened.

To comfort her, I said:”Don’t worry, all of this is happening far away in Germany”.

Her response:

“Then why aren’t they speaking German?”

Kids are always smarter than we think, and very much alive to grown-up bullshit.

*****

One interesting little fact I should have included in the article:

In francophone Belgian comics, ‘Flash Gordon’ was translated as ‘Gordon l’Intrepide’.

But in French comics, Flash was known as ‘Guy L’Eclair’. And separate translations were made for each.

Oscar Wilde famously quipped that Britain and America were two nations separated by a common language; well, the same may be said of France and Wallonia (francophone Belgium).They really are different countries.

Francophone Belgians, by the way, are as annoyed by foreigners taking them for French as anglophone Canadians are by them assuming them to be American.

It’s one thing Agatha Christie got right about her Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot!

Awesome article and some great comics pages; that “Le Rayon U” looks like it belongs in an old “Heavy Metal” issue!

Yes, very good article indeed!

Thank you!

There are a mistake : Hergé isn’t dead in 1883 but in 1983…

And the standard format for french and belgian comics is not 62 pages but 46 or 48 pages — the 48CC as french comics editor and author J.-C. Menu calls it.

(And, French, I ignored Uderzo has drawn a superhero comic… Thanks !).

ps : After war, Van Melkebeke worked unofficially — as scenarist — on someone Tintin comics ; and, maybe, on one or two Blake and Mortimer.

Whoops! Noah, can you correct that Hergé date? Thanks, mFausse.

You’re right about the length now, but those first comics were at 62 pages.

Pingback: Cantinho da BD #21 - Não Percas