When Noah suggested that I write something new for HU, I immediately thought of One Piece.(Official page from Viz here.) It is a monster of popular culture; the highest selling manga ever in Japan and one of the best selling worldwide. It competes handily for mainstream Japanese comics awards. Anything with this sort of momentum should be engaged seriously, if not taken seriously. At twelve years of operation, it’s now an institution of modern day manga.

On top of its universal presence, I have real affection for One Piece. After watching the glorious auto-destruction of the Shonen genre in Gurren Lagann (an adoring commentary on shonen that I highly recommend), I thought that I was done with watching a team of young misfits gain exponential power. But Oda’s work has brought me back again and again. Full disclosure: I’m not up to date on its decade-plus run so this will be written with only partial familiarity with the work.

The storyline of One Piece, while clever, is not exactly innovative. Monkey D. Luffy is a precocious young boy who lives in a planet that is covered in oceans and ruled by a corrupt world government who enforces its will through an omnipresent navy. The navy is opposed by both good and bad pirates, the much revered heroes and villains of the world. The greatest pirate of all time, Gol D. Roger, left his legendary treasure, the One Piece, at some mysterious location before he was executed by the world government. Now every pirate crew is looking to find it. Luffy’s adventures start when he eats the mysterious Devil Fruit, which gives him the ability to manipulate his body as though he were rubber. He sets off in search of the One Piece and acquires a crew along the way.

Much of the series does little to depart from Shonen tropes. Luffy’s crew (the “Straw Hat Pirates”, named for Luffy’s treasured headgear) are a bunch of ambitious teenagers who all aim to be the very best in what they do. Much of the series follows a predictable formula: the Straw Hats come into a situation en media res, the unjust bad guys seriously underestimate them, and they ultimately prevail through sheer strength of will. He and his crew constantly amaze everyone that they come into contact with. Although they encounter some setbacks at times, there’s never anything that feels like a truly insurmountable problem. It even has a shapeshifting reindeer named Tony Tony Chopper who looks like he was created by a focus group who were asked to free associate on kawaii.

Tony Tony Chopper in all his marketable glory.

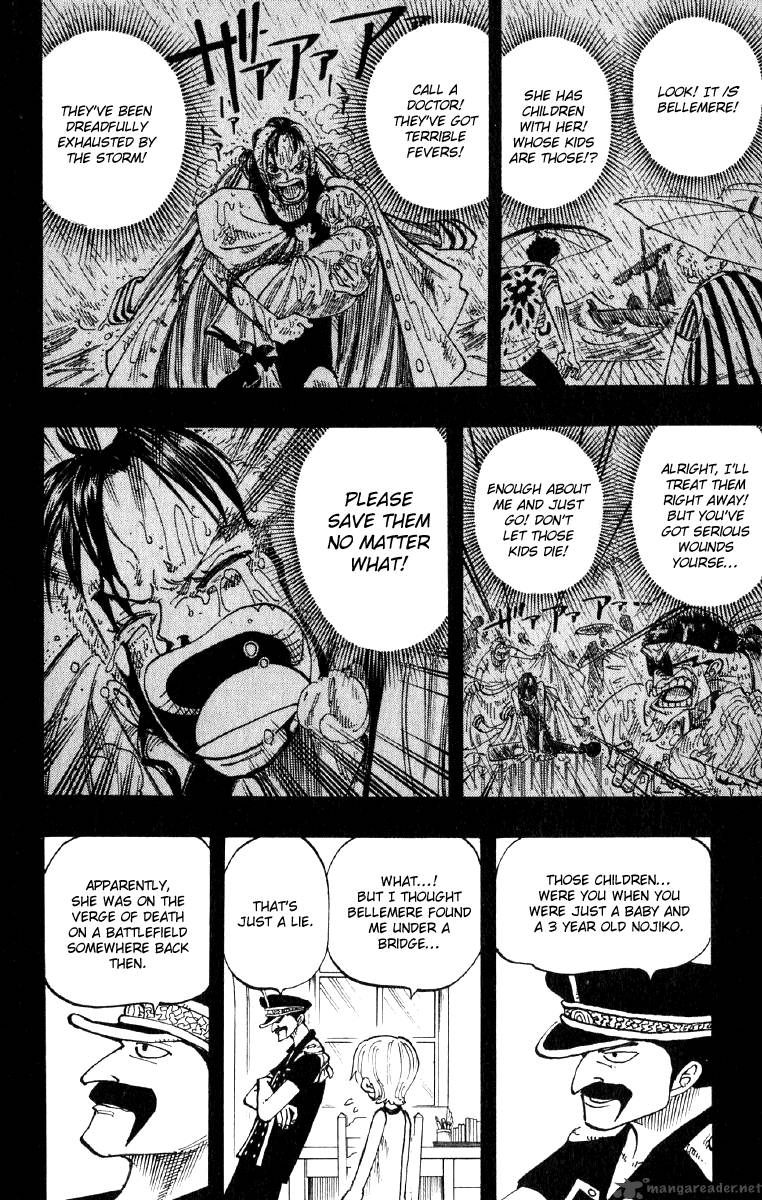

Since this is Hooded Utilitarian, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that Nami, the primary representative of womankind in a work that is avowedly written for young boys, is criminally underwritten. Oda handles gender issues with the familiar fumbling of a teenage boy. There are charming touches, like when Nami “outmans” the power fantasy character Zoro by drinking him under the table. But, tellingly, that moment is undermined when Zoro reveals that he was faking because a true swordsman would never get so drunk that they couldn’t be on guard. In my experience with the series, the most problematic narrative moment is during Nami’s origin arc, which starts with her attempting to assert her independence by stealing money from the rest of the crew and then returning to her home island to deal with her checkered past. Predictably, the rest of the (all male) Straw Hat pirates pursue her. Then we’re treated to a very interesting story about female independence with Belle-Mère, the adoptive mother of both Nami and her sister. Belle-Mère is a former marine who finds the girls on the battlefield and raises them alone with little to no mention of men. Though her narrative is plagued with the same pre-teen ogling that is present on nearly every page of One Piece, it is an interesting departure from the norm.

The story of Belle-Mère

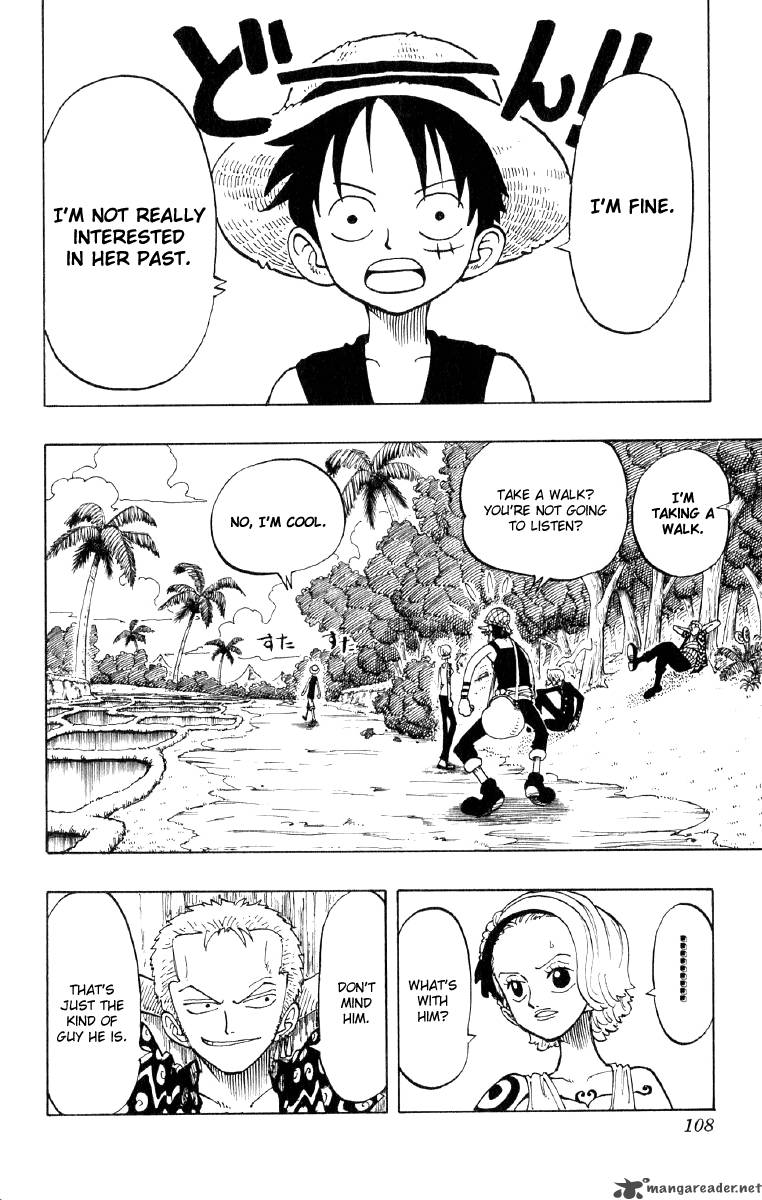

This interesting attempt at a feminist backstory is undermined in the main narrative when Nami is entirely overwhelmed by her predicament with the fishman pirate lord Arlong. The key point in the story arc culminates with her collapsing like the little girl that Oda clearly thinks that she is. In that truly depressing scene, she is forced to ask the ever-capable Luffy for help. Predictably, Nami’s otherwise interminable problems with Arlong are quickly resolved when her male crewmates beat the living shit out of him and his crew. Where (relatively) deep female character fails, brute unthinking strength (and “friendship”) will always win.

Nami gives up and lets the men do the work.

I couldn’t resist including this page. It says so much.

This problematic view of female incompetence defines the dynamic of the Straw Hats throughout their adventures. When shit hits the fan, Nami is often consigned to a sideline role with the comically impotent (and troublingly Semitic?) Usopp. This reaches its nadir during the climax of the Alabasta arc where the two characters have an uncomfortably frank “conversation” about their roles within the group.

While there might be some sort of feminist case here, I’m not about to make it.

By the time the super-powerful Nico Robin appears on the stage as a strong female character, the role of the women in the series is already tragically well established.

The work’s problems are only exaggerated by its adaptation for television. The anime version of many Shonen franchises are made worse for the transition, and One Piece is no exception. While the bright colors bring Oda’s already eye-popping world to life in some interesting ways, the bulk of the series is glacially paced and full of unimaginative filler that dilutes the bouncy, free-roaming nature of the original work. As anyone familiar with the adaptations of Dragonball Z and Naruto knows, watching a Shonen series is usually an excruciating experience.

Ethically and politically, One Piece is often an indulgently illiberal work. The Straw Hat Pirates epitomize honor, loyalty, determination, strength, and self-sacrifice. As mentioned above, the world government is something straight out of a libertarian nightmare. At one point, Luffy and his friends encounter a series of super-powerful pirates that have aligned themselves with the government. In exchange for being able to pillage with impunity, these “Seven Warlords of the Sea” agree to do the bidding of their naval establishment masters. Again, problems are ultimately solved through brute force; though there are moments of emotional conflict, they often have to sit on the bench while the “real” battles are fought by Luffy and his bros. The focus of the interminable Alabasta arc is on how idealists need the arms of strong and violent men in order to make their passion for peace into a reality.

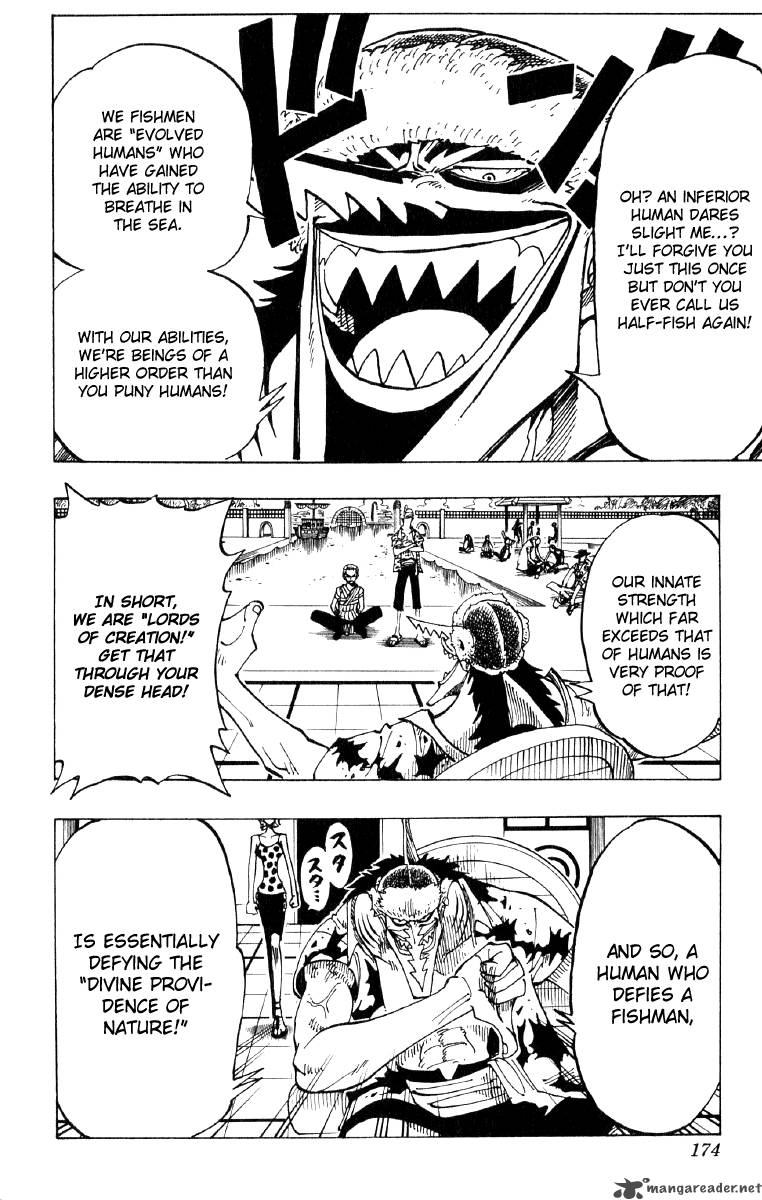

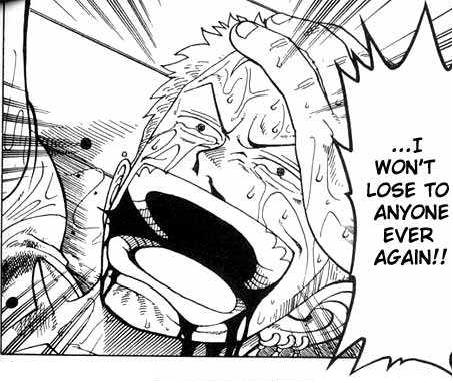

There are exceptions. The Arlong Park arc gingerly deals with issues of inequality. Arlong himself is a fishman who thinks that his species is genetically superior to the human race. He rationalizes his domination of the humans that live on the island alongside him with tones appropriated from both Thrasymachus and Darwin:

Arlong doesn’t really understand Nietzsche

Though it’s clear what sort of world-view Arlong stands in for here, it’s not clear what his defeat at the hands of Luffy signifies. Luffy beats Arlong at the end of a battle of attrition; he doesn’t find the key to his victory in Arlong’s arrogance or anything else other than his own infinite determination. In this context, it seems like the point is a bizarrely Hobbesian one. Be careful about asserting your superiority to the people you see as beneath you. After all, there could always be someone that’s stronger.

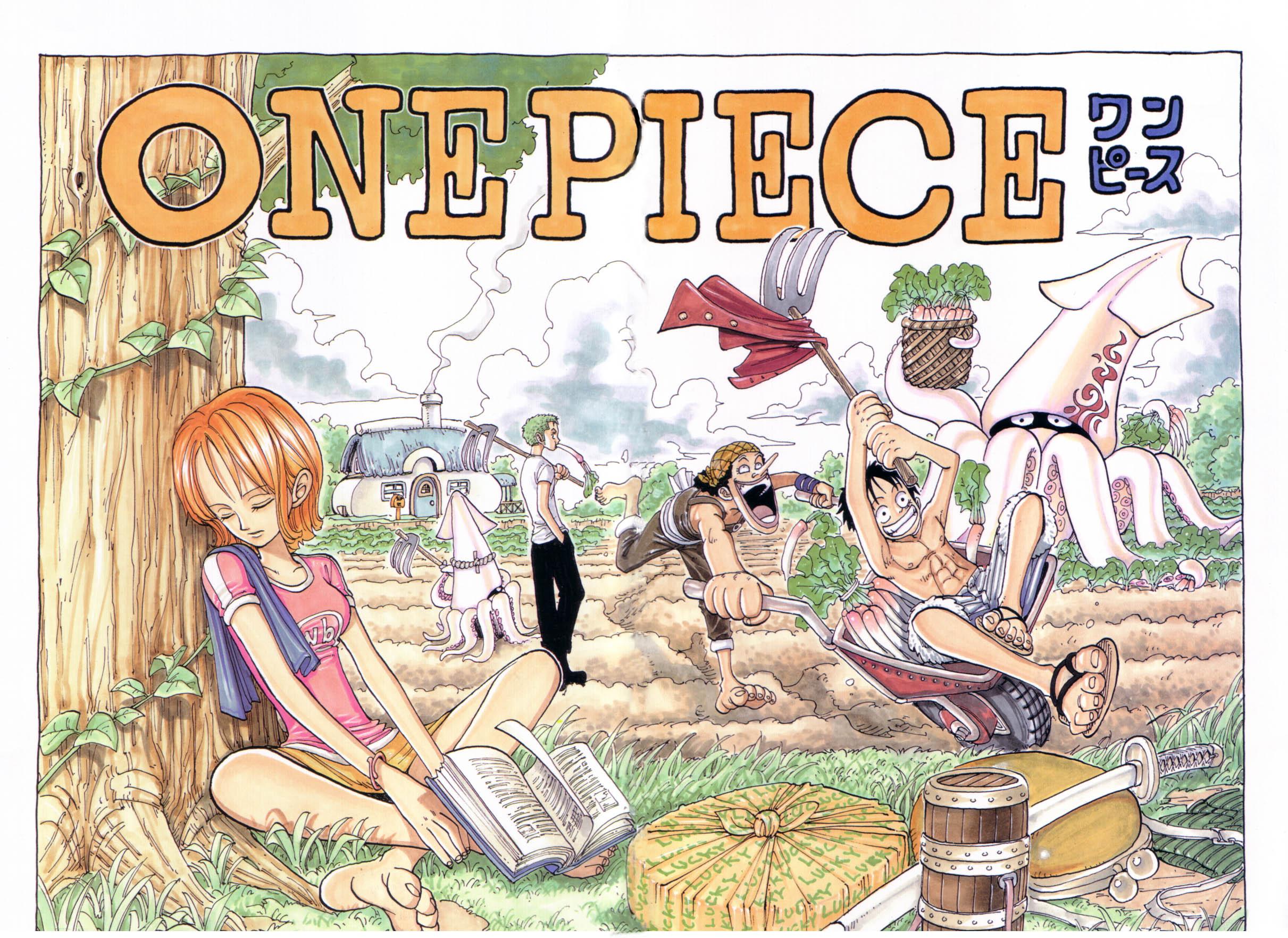

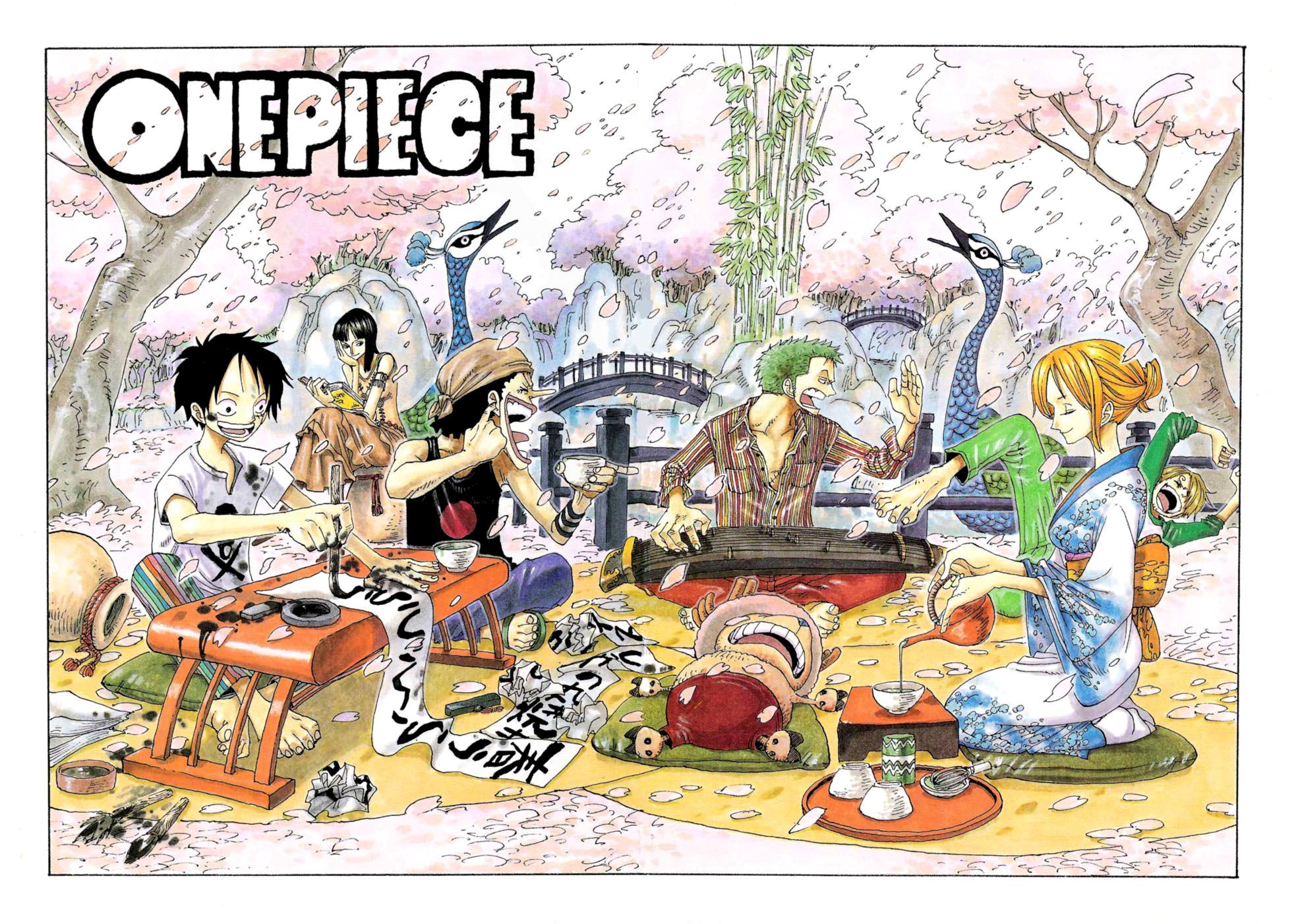

For all of its obnoxious flaws and derivative character, I still love One Piece. This is due in no small part to my affinity for Oda’s aesthetic sensibility. Oda reportedly works every day of the week and sleeps an apocryphal four hours a night. The work’s dialogue is utilitarian at best and inane at worst, but visually Oda and his team have refined a certain Shonen Jump style dating back to early Dragonball. One Piece competes with Naruto for the attention of today’s manga-consuming youth, but a quick look at a page from both series will reveal why Oda’s book is the better one. Naruto is a boring continuation of the most mundane visual elements of the genre as its been for the last 40 years. One Piece has characters that look as though they stumbled in from wonderland. Oda’s characters bloat and burst at the seams. They pose and explode with childlike joy. In contrast to the null-environments of the Toriyama legacy, Oda lovingly constructs environments thick with unnecessary detail. It only takes a look at one of the lush vignette cover pages to see how adroitly he and his reportedly small team of assistants overflow the page. As a result, the travels of the Straw Hat Crew feel like real adventures. It never seems like Luffy and his friends are going to the same place twice.

The crew resting up.

I also find the emotional tone of the series nostalgically charming. I am embarrassed to admit the number of times that I’ve bought into its sentimental juvenalia and found myself tearing up. I like to think that’s because for all of its over-the-top histrionics, One Piece still treats its protagonists like old friends. The characters all manage a dimension of gripping personality (at times) and stick together through thick and thin. In a pop comics environment where cynical egotism is often mistaken for realism, One Piece is often a breath of fresh air.

These are all surface expressions of the underlying problem of One Piece. Like its protagonist, the world of One Piece is rubber. It flexes to allow plots to develop, but quickly bounces back into shape. There are very few deaths; even the worst villains are often simply removed from play for awhile. The deaths that do happen are used to develop the emotional plot. The characters of One Piece are sentimental and charming, but few things really touch them. Almost every experience they have bounces off their well designed surfaces. Their adventures, at best, are surreal daydreams on the beach.

I once told my friend (and fellow HU contributor) Jacob that you need to put some time into One Piece to see if you can love the characters. If their playful and affectionate depiction charms you, you may really like the series. However, even if your sensibilities are a little too refined for One Piece‘s adolescent exuberance, I’d encourage you to page through the work online simply to see Oda’s indomitably energetic visual imagination in full bloom.

_____________

Owen writes regularly at his blog The Inebriated Spook.

A really good read, Owen. I think the problems you’ve identified with One Piece’s narrative are problems that extend to the entire genre of Shonen Manga, but also recognized that One Piece engages them more deceptively by /suggesting/ it’s characters can escape their own narrative conventions before trapping them back in it. You also brought up an interesting point about Oida, and the myth of superhuman labor that surrounds him. Why is the image of the mangaka and their eternal labor such a popular one? I’d love to read more about that question.

Thanks a lot Patrick! I heard the Oda-myth from Jacob when he started reading the series. I thought it matched the sort of wide-eyed, caffeinated spirit of the work.

I would speculate that the answer to your question has something to do with the assertion that the Japanese “as a culture” have a brutal work ethic. I don’t know how much that applies anymore (if it ever did), but it definitely lends itself to mythologizing.

About the mangaka labor, Oda himself said the he draws pretty much anything that’s alive:

“D: Oda-sensei, you have assistants like other artists, right? Other manga you can recognize when stuff is obviously done by assistants, but when you look at One Piece from the first volume, it doesn’t seem that way! Do you draw everything that appears in the art? P.N. Girl Who Reread it from Volume 1

O: Absolutely not, I couldn’t draw every single thing. My staff draws the backgrounds for me. When I show them my setting art, they deconstruct it and ensure that everything gets displayed perfectly. My staff is incredibly talented. Perhaps the difference you’re seeing is that I draw 100% of anything “living or moving”, including mob scenes, animals, smoke, clouds, seas, etc. When you leave the movement up to someone else, it can’t help but cause abnormalities in your art. It becomes awkward. This is all just my particular obsession within my work, however.”

http://onepiece.wikia.com/wiki/SBS_Volume_52

i think this just reinforces the myth about hardworking mangaka if you consider this type of work ethic in a weekly serialization.

I’ve been obsessed with One Piece for the last several months, during which I read the entire series to date, and I agree with your criticisms for the most part. I’ll have to think some more about the treatment of female characters, and what the triumph of what you characterize as “brute, unthinking strength” means. I will note that if you read more of the series, you’ll see Oda continue to develop his semi-libertarian views, as well as the issues of inequality. I found this moment from volume 65 especially interesting. And yes, the emotional tone is amazingly well done. I’m not ashamed at all to admit that certain stories have brought tears to my eyes (especially the climax of the Water 7/Enies Lobby storyline), and I’m more invested in these characters at this point than I’ve probably ever been in what happens to the spandex-clad heroes of American comics. It’s definitely a shonen series with all the quirks that that entails, but I think it’s more emotionally effective, deeper, more exciting, funnier, and just plain better overall than just about any superhero comic out there.

I don’t understand why you like this.

You praise it, but go on to explain that it’s shallow and the only good thing about it is the art. The only other thing you offer to support the idea that it’s redeemable is that it makes you think of your childhood.

Matthew, I’d say that my embarrassment with being emotionally involved with the series has to do with how the emotional gestures that it makes are very coarse. There is very little that’s nuanced or original about the emotional texture of One Piece.

Johnny, I like to see pop well executed. One Piece is charming as far as it goes, but it ain’t Tolstoy, and I don’t expect it to be. Just because something is shallow doesn’t mean that what it does have to say can’t be well expressed.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | IDW’s CEO talks digital strategy, book market | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment