Michael DeForge wants you to know that comics aren’t just for kids anymore.

The cover of DeForge’s Incinerator is a bland desecration of comics past. Snoopy’s instantly recognizable backside suffers a decontextualizing detournment, transformed into a torso for the wrong bald-headed kid walking through a typically scrungy alt comics landscape, his tail a bulbous, inexpressive phallus between legs lifted with jaunty incongruity above the junk and debris. Bleak plant-like and rock-like globs ooze at stochastic intervals, the stripped-down iconic style suggesting the world of Peanuts determinedly uglified by underground grunge.

The adultification, not to say adulteration, of Peanuts is a familiar alt-comics trope. Chris Ware and Dan Clowes tend to try to capture Schulz’s rhythms and then layer on sex, drugs, scat, and other supposed markers of maturity. DeForge, refreshingly, goes for a more blatant approach.

The sad, anatomically challenged amalgamation is set upon by a gang of college students; weaponized maturity mugs the beloved icon of childhood,leaving it groaning in a ditch. The torso has to be taken to a vet while the rest of the sorry creature goes to a hospital. Separated, the beagle body dies, leaving only that bald-headed kid, suffused with pathos.

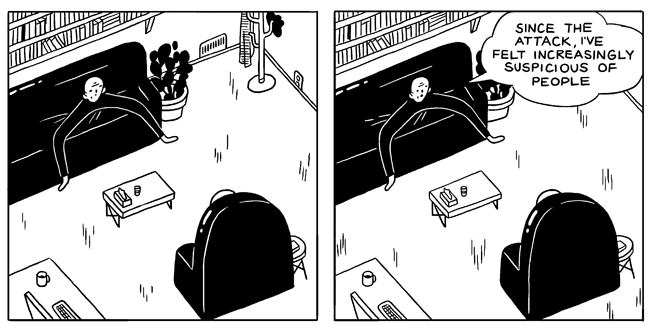

Rather than the Schulz’s grass-level camera, we’re here treated to a crazy look down; a god’s eye view if god were stuck up there with the knick-knacks on the teetering top of a bookshelf. Or, perhaps, we’re looking down at the comics page itself; the sophisticated adults with the book of childhood spread out before us, distant and oddly angled, too small to fall into. We stroke our chin with the analyst in the chair, seeing the mundane neuroses in the formerly fanciful images.

The de-beagled hero goes through his alt comics paces, attending group therapy, reveling in nostalgia for the comic icons of his childhood,

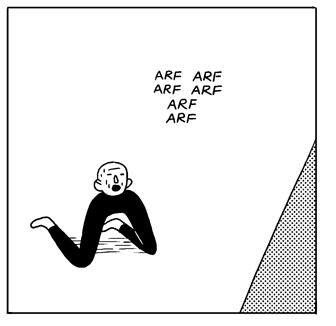

participating in a tender romance. On the final page, the beagle torso, like all those childhood pamphlets, is chucked in an incinerator. The image before it burns is of the girlfriend in dominatrix garb whipping the naked protagonist as he barks. The innocent goofiness of childhood is chucked for sexual perversion. Get rid of that doofy tale and you can see the penis which was hidden there all along.

It’s certainly possible to see this as an absurdist Fort Thunder satire of the alt-comics and underground obsession with Peanuts, with being grown up, and with the conflation of the two — artsy hipster tripped out weirdos mocking the differently literal immature maturities of Chris Ware and R. Crumb. But it’s also possible to see Incinerator as a kind of avuncular celebration of those immature maturities; a humorous, self-aware, nostalgia for other folks’ nostalgia, and for the role it’s played in the development of comics past.

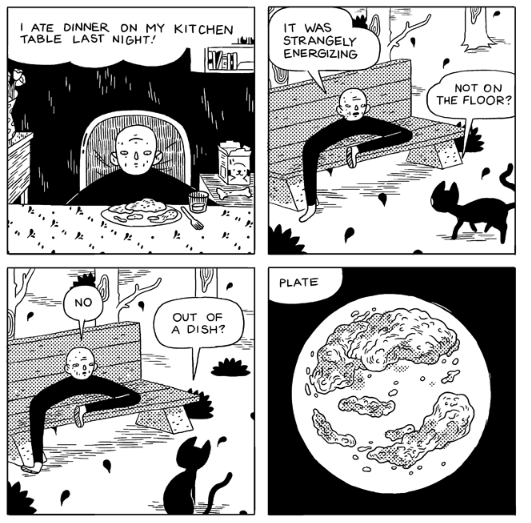

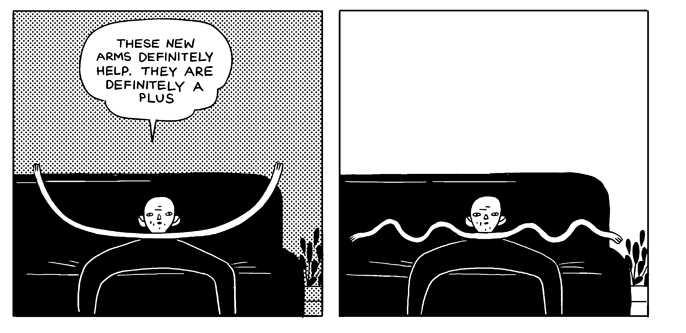

Growing up, trying new things, is energizing. The Rorschach-blot-feces lunch forms an interesting pattern, it’s very repulsiveness an ironic attraction. Adulthood is still what’s on offer, but an adulthood less bleakly blank than Ware’s or Clowe’s, in no small part because it sees Ware and Clowes as comfortingly familiar predecessors. Thus, adulthood here means building on Schulz’s absurdity (and Clowes’ and Ware’s) rather than on his (or their) existential despair. It means using Peanuts, and Peanuts’ successors, as visual tropes rather than as a blueprint. Adulthood becomes an at least intermittently pleasing agglomeration; lack of integration, the loss of the coherent circumscribed world of childhood, becomes its own pleasure. The lost thing provokes not just nostalgia, but joy at the missing piece. If Lacan’s child looks in the mirror and feels celebratory at the illusory image of an integrated self, DeForge’s adult looks at the comic and feels celebratory at the illusory image of a haphazard collage cyborg, the aging self as bits and pieces of one’s own past.

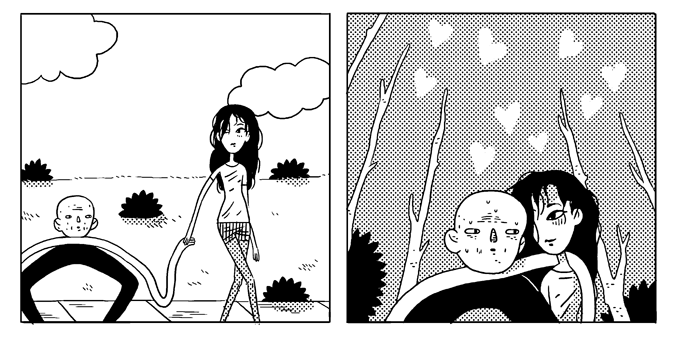

Part of that delightful adult collage, it seems, is the image of a woman. One of the female college students in the crowd at the beginning of the story later becomes our protagonist’s rom/com, Jeff Brown sweetie, and finally his dominating mistress.

That flaccid arm across her shoulder contrasts with the cruel, stark phallic trees framing the hearts which seem less like a vibrant expression of love than like de rigeur filligree tacked up to the moire background. This is not a story, but the garbled image of a story; not love but the parodic potency of recognizing parodic lack of potency. The girlfriend, as marauder or sweetie or dominatrix, never speaks. Unlike Schulz’s Lucy, or Sally, or Marcy, or Peppermint Patty, she has no tale of her own. The protagonist’s self is the past, but the woman’s self is simply image, signalling various comfortably denuded narratives of coherence: teen rebellion, love, sex. The silent, faceless Snoopy is discarded, the silent, many-faced female is picked up with new arms. The one coherent attribute of adulthood is a recognition of absurdity. All the rest, no matter how soaked in sentiment — be it comics, woman, torso, or heart — is just a part of the caducous bricolage.

A wonderful piece of criticism, Noah. Recently, you have really highlighted how few and fetid the tropes of adulthood are in many alt comics. I thought for while about contributing to HU’s potential DeForge round table, but the more I looked his pages, the less I could see. By the end, it seems that the effect of these comics came from taking a childlike image — a rubber-hose cartoon, say — and adding 10-20 blemishes or small drops of perspiration and ooze. These are the signifiers of a limply nightmarish realism: happiness is a warm puppy; maturity is moisture.

“These are the signifiers of a limply nightmarish realism: happiness is a warm puppy; maturity is moisture.”

Ouch.

I’m…not completely negative? The piece is somewhat ambivalent, I think. I do prefer the absurdity as adulthood to boredom as adulthood, which is what alt comics goes for. And I like some of the art; Snoopy as torso is pretty funny and weird, and the view-from-above panel is nicely vertiginous and bizarre. I feel like he could do something I was into, though ultimately this isn’t it.

If anybody out there wanted to do a positive DeForge write up, though, I’d love to print that.

“It’s certainly possible to see this as an absurdist Fort Thunder satire of the alt-comics and underground obsession with Peanuts, with being grown up”

The Snoopy incineration does seem a bit like a dig at the lit comics crowd and he could be making fun of their tropes – everything from Chester Brown (and his whores) to Dan Clowes’ Wilson (and his faeces). But there’s no doubt that DeForge is fond of absurdist/bizarre narratives which makes the comic more ambiguous than your standard Johnny Ryan takedown of Crumb.

More good writing, Noah.

“Get rid of that doofy tale and you can see the penis which was hidden there all along.”

I think that this is an interesting moment in your piece and a real insight into your critical approach. Where you see this as a Freudian story, is there any reason for us not to see it as parodic of the idea of adulthood as an absurd necessity? I think that if there’s a interesting critical bite to Incinerator, based on what’s on hand here, it’s that it is critical of the exact sort of self-mutilation and socialization that is “shedding our childhood” for more mature attachments. Why not go with Deleuze and Guattari rather than Lacan and say that Deforge’s comic is about how “maturity” is more about normalizing yourself in order to become acceptable and productive (as a worker, as a parent) than it is about any sort of necessary process?

In fact, the third to last panel where the “protagonist” is barking like a dog as part of his fetish suggests that far from moving past his non-sexual childhood attachments, he’s simply been forced to cathect them differently. He’s forced to move his desires into the strained realm of heterosexual oedipalization after his interaction with the college kids. Seen in this light, Incinerator is about how despite the best efforts of socialization, we never totally transform our childhood attachments and they never fit nicely into mommy-daddy-me. We just add layers to our perversions under pressure of socialization. As you say, the hearts are pinned to the background of the normal romantic scene as a forced trope, not an expression of desire. The protagonist talks to his father but those scenes are contrasted with the scenes where his desire forces its way to the surface. He tries to love his loss and get arms to be like everyone else, but in the bedroom he can’t help but give in to his desire in the only way that is allowed (sexual, hetero) after his socialization.

This makes Deforge’s work a more incisive criticism of Clowes and Ware. They’re trying desperately to distance themselves from their own desire while Deforge laughs from the sideline.

How does that strike you?

I do sort of acknowledge that possibility in the piece, I think? (Suat quotes one line where I’m doing that.)

I think for me the problem is that you’ve still go the problem with black comedy/absurdity, where the comedian/absurdist is the ultimate adult/knower. That is, DeForge is making fun of Ware, etc. and their pretensions of adulthood, but his own pretension ends up being that the satirist/absurdist is the *real* adult. That’s kind of my point in talking about the way he treats the girlfriend; for all the protestations of being cooler, more mature, more knowing, you’re still at a place where the supposed childhood thing is actually able to imagine women as people, and the supposedly more sophisticated thing isn’t.

Does that make sense? I don’t think your reading is wrong; it’s just not where I end up in thinking about the comic.

I don’t know, maybe you considered it negative, but you made some points in this piece that made me like DeForge’s work even more—-and I already liked it.

I honestly think that I can accommodate that within my reading. If anything, the “more sophisticated” interaction with women that you point to further unveils the pressures of the sort of normalizing neurosis that I want to talk about. It pushes Deforge’s protagonist to see women as socially reproductive pairings; if anything, it’s another criticism of the sort of “adulthood” that Deforge is deriding. It’s clear from your piece that you don’t think that Deforge is straightforwardly accepting this sort of relationship as organic.

James, like I said, I’m ambivalent. I’m certainly happy to have it make you like him more!

Owen, I think that’s fair. There’s no effort to see women as anything but memes, though, is kind of the thing. He’s mocking the way women are figured in this kind of adulthood, but since women are so important as a marker of adulthood, it seems like that bleeds over fairly readily into mocking women, or the attachment to women, period.

I think it is a satire of alt comics default narratives of adulthood to some degree. But it’s a satire in which the point is still that the reader/creator is more knowing, and a world in which women are still essentially viewed not as people in themselves but as markers of adulthood.

I’ve talked about this before in other contexts, but…I’m not generally convinced that treating women as misogynist memes avoids misogyny as long as misogynist memes are all you see and the story remains about male psychodrama.

I do like your reading though. I think DeForge is definitely working with the idea of adulthood as normalization/loss as well as achievement. Doesn’t that fit in with the usual alt comics nostalgia though, esp. if childhood is figured as Peanuts? That is, Ware is all about adulthood as cruel conformity too. There’s a love/hate tension there, which DeForge both mocks and I think reproduces.