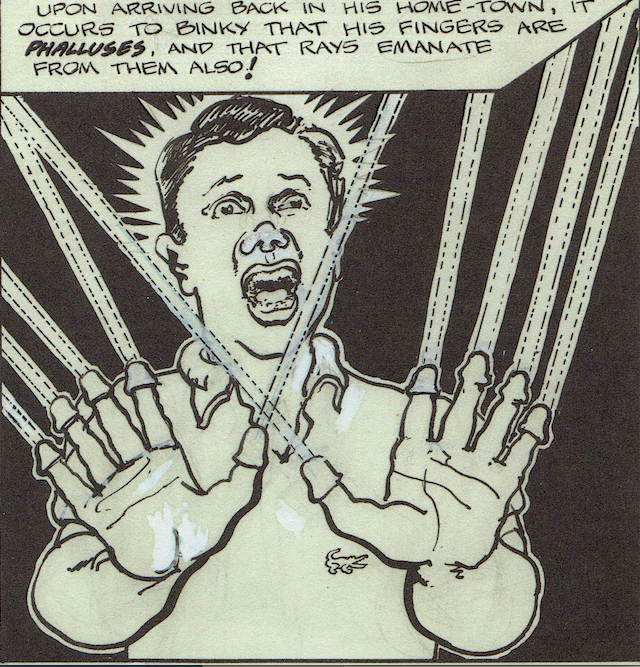

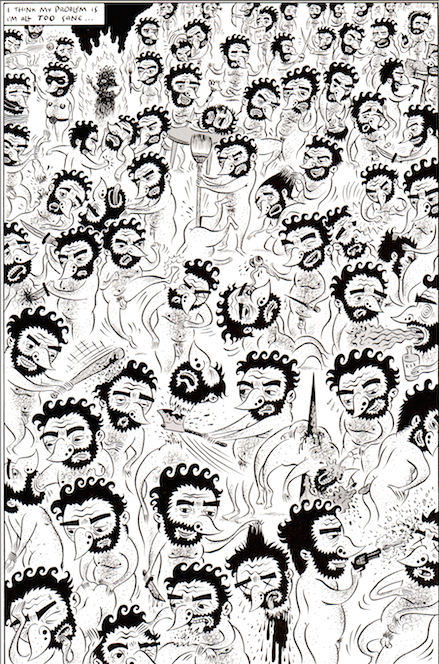

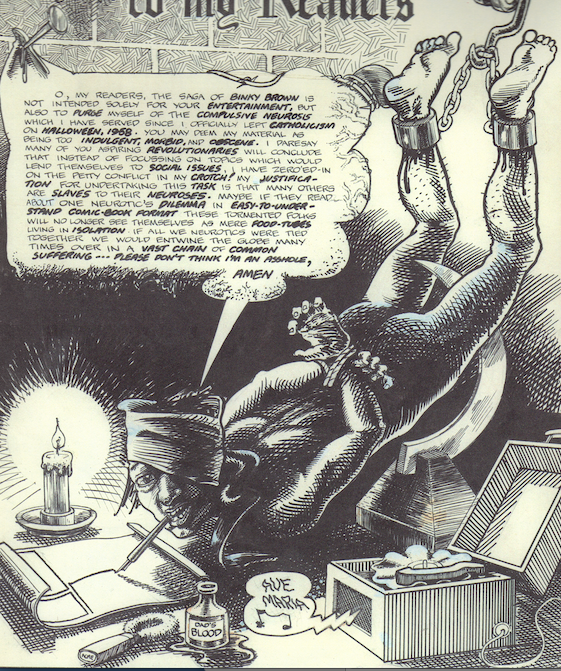

In 1972, the genre of autobiographical comics was born unto us by a mysterious penis with magical powers. Technically, of course, there was a man attached to the penis, though mostly he was just in its thrall. The legacy of that immaculate conception lives on today in the long line of tortured male cartoonists who express intense dissatisfaction with their lives and art via detailed accounts of everything they have ever done or imagined doing with their genitals.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that. As with any subgenre, some works of dick-centric autobio are good, some are bad, and some are in between. Justin Green is not just first, but also probably the finest, of its lauded practitioners, including Robert Crumb, Ivan Brunetti, Joe Matt, and Chester Brown (to name just a few). Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary is not exactly a meditation on Green’s struggles with obsessive-compulsive disorder, but is a visceral account of what it’s like to live with that condition—and the way in which Green rendered his interiority still strikes me as singular in what has since become a very crowded category.

In Binky Brown we see two interwoven themes that appear with great frequency in autobio: sexual obsession and the torturous act of cartooning.

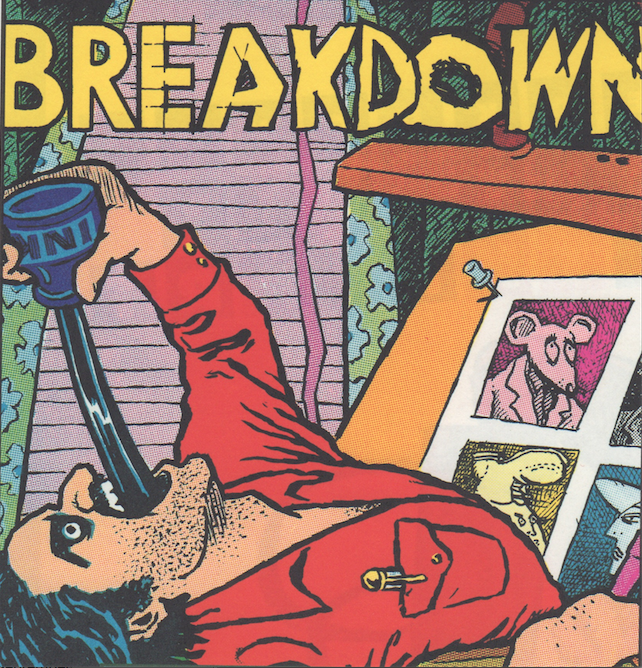

Cartooning is hard, god knows, especially when you’d rather be doing PEEN STUFF. The tough compromise that some men have made is to simply draw their dicks constantly, very often sacrificing any semblance of story or self-respect in the name of their art, such as it is.

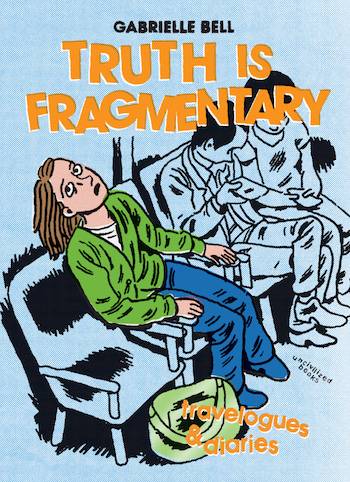

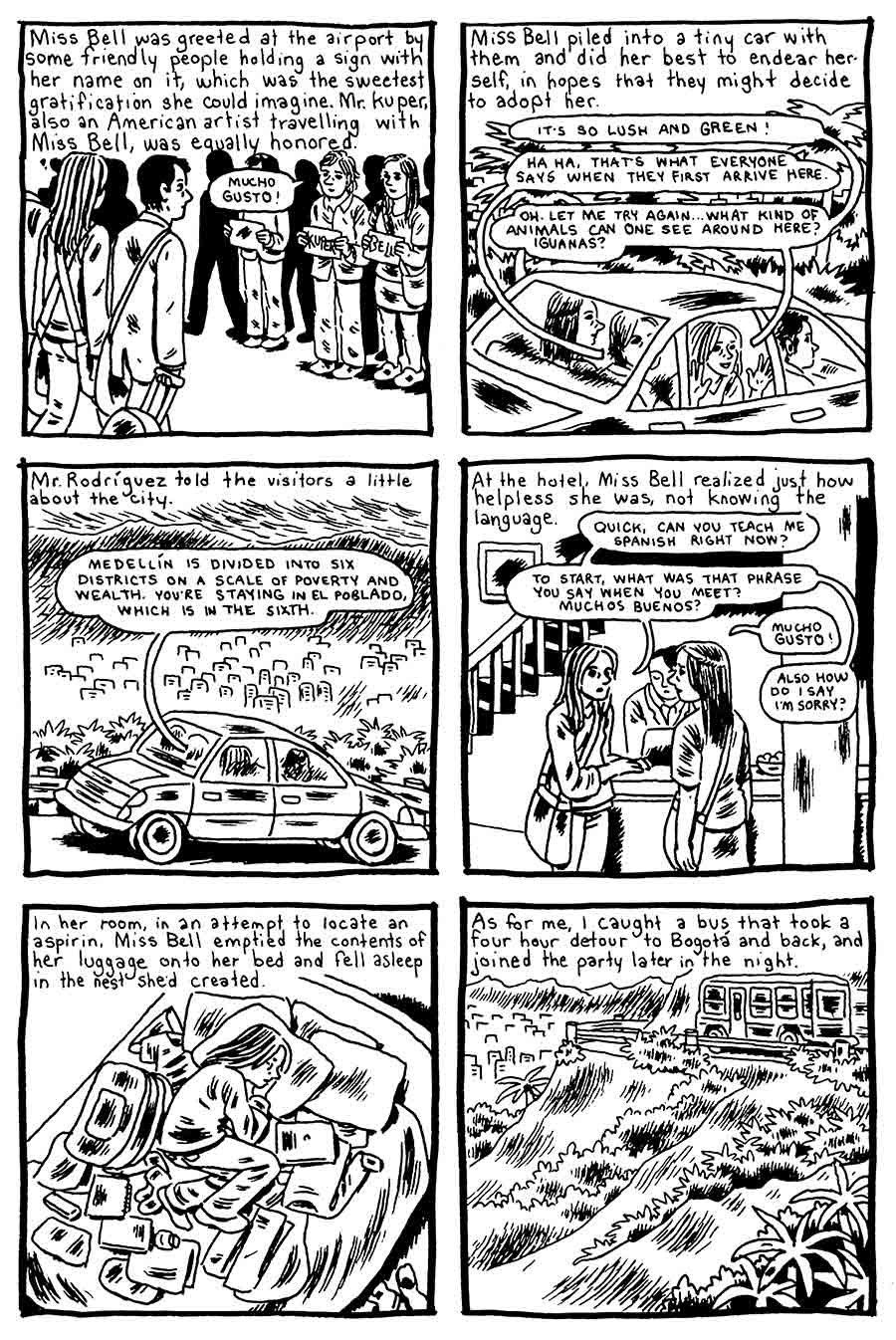

Recently, I was reminded of the inalienable right of tortured male cartoonists to create work — entire catalogs of work — about their dicks when I read this “positive” review of The Truth Is Fragmentary at The Comics Journal, where reviewer John Seven explores Gabrielle Bell’s conflicted relationship with making art. Within it is a note of condescension that is perhaps most palpable as the review begins.

Poor Gabrielle Bell. You’d think a cartoonist’s life would be perfect for her loner tendencies, but she’s constantly having to deal with being flown to comics events around the world and facing expectations to interact with the community that comes with cartooning. She doesn’t always do so well.

Which sure, Bell writes a lot about loneliness and social awkwardness, but the subtext here is that she whines about it. There is an implicit question — Why on earth would she complain about her “perfect” cartoonist’s life? — followed by an implicit answer. The poor gal simply can’t handle the basic functions of her job.

Antisocial behavior is, of course, celebrated in men’s autobio, which rarely traffics in stories about friendship (as Bell’s often do) or even feature any round character that is not the protagonist — or, more specifically, the protagonist’s penis, which is all at once the hero, the villain, and the love interest of his story. Anyway, it’s not until much later in the review that Seven (who seems to hold Bell’s work in high regard) begins to ask much more explicit questions about his subject.

Why does [Bell] challenge herself to these diaries when she also often mentions how dissatisfied she is by the prospect of doing them? What is she trying to attain by sharing these works that could easily function as private, daily exercises in cartooning of no interest to anyone else but the cartoonist?

Why, indeed, is Bell a cartoonist at all? Can you imagine a reviewer asking this existential question of one of the tortured men of autobio?

Mr. Spiegelman, gee, you don’t look so hot. Are you sure about this comics thing? Maybe you should take a break. Adjust your meds. Lie down or something.

Heyyyyyy Ivan. You okay, buddy? Couldn’t help but notice that you constantly draw yourself committing suicide. Have you ever considered keeping those thoughts to yourself?

Justin Green. Dude. I know your penis is about to invent a whole new art form, but are you sure it’s worth THIS?!

These questions seem preposterous because when men share their inner worlds, whether they’re glorified bathroom wall graffiti or something more sophisticated, we automatically see those thoughts and feelings as worthy of being shared. No justification is required. And if those men have to endure some sort of trial or struggle to get that art out into the world, all the better. The comics world loves nothing more than some good old-fashioned MANGST.

Of course, Seven writing about Bell is just one example of how comics culture questions the very existence of a women’s autobio. Lest you think this phenomenon is limited to male critics — or to critiques of Bell — I’m very sorry to report a conversation I once had with a well respected lady cartoonist who spoke to me at length about her distaste for women’s autobio, which she considers frivolous. She singled out, among others, Vanessa Davis, whose charming work she referred to as “teenage twaddle” that “should have not been printed.”

I can’t tell you how irritated I am that they use perfectly good paper and product and marketing and everything else,” she said. “They put money into such egocentric crap.

Women in autobio can’t win, really. If they portray themselves as happy, their stories are too light to be taken seriously. If they explore any sort of negative emotion, they’re perceived as complaining. And women who mix the two approaches run the risk of being deemed uneven, as in this review of Hyperbole and a Half, where Stacie Williams criticizes Allie Brosh for drawing “relatively frivolous narratives” about “unremarkable activity” alongside her devastating accounts of clinical depression.

The inherent worth of women’s autobio is hardly a given. Its authenticity is constantly called into question — and all too often, the work is found to come up short. Meanwhile, many people labor under the delusion that female cartoonists are accorded the same critical treatment as their male counterparts. I’m reminded of those men on the street who are always telling me to smile. Why are Gabrielle Bell’s comics so glum? And what am I so worked up about, anyway? Let’s raise a glass to the latest perk in Bell’s perfect life as a cartoonist: John Seven gave her a good review. :)

“Can you imagine a reviewer asking this existential question of one of the tortured men of autobio?”

I can picture Noah asking himself some questions along the same lines when encountering the 9/11 work of Art Spiegelman. As in, why didn’t he keep that shit to himself.

I don’t know. I like Bell’s comics but there sure is a lot of “twaddle” and “egocentric crap” (emphasis on the latter) in comics autobiography in general. And way too much praise ladled on the genre. I’m willing to give the Vanessa Davis book another try but it sure seemed like another comic in a long tradition of autobiographical rubbish. Certainly all those male cartoonists writing about their masturbatory habits in the late 80s and early 90s should have been excoriated much more thoroughly (instead of praised for their courage or whatever). Didn’t Chester Brown just write about his penis again recently? (yawn?)

I think it’s probably good to note that the most highly praised autobiographical comics in recent years have been by women – Alison Bechdel, Marjane Satrapi, and Ulli Lust. The men are well out of the game and good riddance to them considering the staggering lack of introspection in their comics.

Johnny Ryan sneered at male autobio work pretty entertainingly. (

I do agree with Suat’s comment that for the last couple of years, the most highly lauded (and publicized) autobiographical works have been by women. Alison Bechdel and Roz Chast recently won big awards, (this defense of the ‘literary’ quality of their work on Salon is a great read. Especially in light of last year’s ‘death to the literariness’ moment.)

Meanwhile, male cartoonists seem to be making a jump from memoir (often feminized,) to fiction, perhaps hoping to create the Great American Graphic Novel. Look at Ware, Thompson… even Crumb’s tackling of the Bible.

I loved and laughed aloud at this piece, and while I’m not sure Seven’s review supports the extent of your argument, it rings true to me and my experience in comics. It especially resonates with my feelings about comics fandoms, and the construction of male geniuses.

I felt like Seven seemed a bit unsure how to approach Bell’s work? Part of what I really like about her is she doesn’t exactly do autobio. She’s always tipping over into outright fiction in autobio form; you really can’t always tell for sure what’s true and what isn’t. Seven acknowledges that, but then he also seems to be engaging with her work as if she’s confessing truths about herself.

Oh yeah, I would never argue that women get no respect for autobio. Alison Bechdel just won a genius grant! And Bell, my central example here, is herself well respected. I just think that the worth and authenticity of women’s stories is interrogated in a different way than their male counterparts–particularly when the subject is unhappiness (or lack thereof). That it is interrogated even within the context of a positive review is especially notable.

Kailyn, I saw (and loved) that Chee piece. I thought it was so fascinating, not in the argument he makes for comics being legit, but in that he’s still fighting that battle as a judge on these panels! Wut. Nuts. Anyway, I’m glad this piece made you laugh.

I wonder if it’s worth noting that the praise we’re talking about for women’s autobio (esp. for Bechdel and Satrapi) seems to be most loud from comics’ crossover audience. I saw a lot more coverage for Paying for It at comics outlets than Are You My Mother?, seems like.

Suat, men are far from out of the game. John Porcellino’s new one comes out tomorrow, and no doubt we’ll be inundated with discussion and reviews–including mine, when I get around to finishing it.

Noah’s Johnny Ryan comic seems to undermine slightly the notion that male autobiographical comics are immune to attack, particularly for being self-absorbed, egotistical, whining — even as they, admittedly, are celebrated for being edgy and unflinching. Indeed, it has always been so (bearing in mind the relative smallness of comics criticism).

Maus’s earliest critics (see, e.g., Pekar) attacked Spiegelman’s tendency make himself the victim, the center of the atrocity, the “real” survivor — or at best, a parallel survivor of the survivor. Brunetti was raked over the coals by TCJ’s Kenneth Smith for what Smith deemed Ivan’s valueless world of the self, parading a psychology that vacillated between whining moralism and emotional revulsion. Brown’s recent work was certainly dragged across the coals here at HU (and elsewhere) for variations of same, as have the autobiographical aspects of Chris Ware’s work. (See also Noah’s indictment of David Heatley’s “My Sexual History” — the primary target of Ryan’s page).

Didn’t see your last comment, Kim, before hitting publish. Also, I seemed to have had “coals” cliches on the mind above.

That Kenneth Smith piece was in the same issue as a massive celebratory interview, though, if I recall correctly. It sparked a lot of pushback too (even though gary introduced it as a way to give him some cover.)

Well, most every TCJ interview is celebratory; that’s what they do. So, yeah. My point was not to say that it’s all a wash, with equal numbers of naysayers. But there have been plenty of folks in visible spaces who have taken male auto-bio cartoonists to task for their psychological, moral, and emotional — as well as artistic — shortcomings. The same kinds of language, in its way, that is sometimes (but still, rarely) tossed at women auto-bio cartoonists.

(And I think you might be underestimating the effect of bookending an interview with, say, a few thousand words that call the interviewee a modern moral worm.)

Well, the main effect was to have people call for Smith’s head, I think.

Not that it wasn’t a meaningful thing for tcj to do. I just don’t know that it really changed my sense of what the consensus is, is all.

Yes, instead of “effect,” I should have said “import.”

Hmm, okay. I wasn’t trying to say that men in autobio are NEVER criticized or that women’s autobio is routinely trashed. Let me try again. There is a long tradition of men in autobio who have been celebrated for being unfiltered, for their willingness to let it all hang out, for committing their every passing thought to the page. Dick-centric autobio is the height of that impulse, I guess…and it’s totally ridiculous, but also totally canon. Serious comics. Tracing this impulse back to Green, it’s built into the very DNA of autobio. (please pardon this awful pun.) I think it’s generally understood that the angst of those men was essential to their art. Is it not fair to say that this tradition is lauded? That’s my impression, anyway.

Women’s autobio is celebrated for sure–esp. recently, and esp. by crossover audiences. But it seems to me there is a tendency for critics and even fans to question the legitimacy of women’s stories. This attitude manifests in a lot of different ways. You see it in how early work by women in autobio like Aline Kominsky-Crumb was routinely ignored (though this is obviously changing). You see it when women’s autobio is compared to that of their husbands, as with AKC and Carol Tyler, who once told me that she got a lot of negative feedback from within the comics community for daring to make her husband “look bad” in her You’ll Never Know trilogy.

Other times it seems to be a matter of form. Allie Brosh probably has the largest audience of any woman in autobiographical comics, or maybe any woman in comics full stop, and I’m not sure her work even *registers* as comics with a lot of comics readers. (Again, an impression; maybe I’m wrong?) Lynda Barry is very well respected for her early work, but do you think her last few books w/ D&Q register as autobio? Barry in particular should be heralded as pushing the boundaries of the form *and* the genre…but is she? It seems to me that is not the common impulse. The impulse is instead to say “is this legit?” Is this even comics? And for both of those women–and many others, including Vanessa Davis and even Kate Beaton, I think–there is a tendency to gauge the seriousness or gravity of the work and find that well, maybe a lot of it feels a little too light to be given serious consideration.

Anyway I was reflecting on all of this on the occasion of reading another super tone deaf Bell review at TCJ (which compared her work to Lord of the Rings…don’t get me started). I remembered how much the Seven review irritated me when I saw it earlier this summer. His mocking intro was obnoxious anyway, but when you consider it in light of the fact that histrionic comparisons between comics and torture are a cornerstone of the genre, well, calling her out for her thoughtful concerns about the intersection of life and art seemed to me super sexist, if unintentionally so.

“Johnny Ryan sneered at male autobio work pretty entertainingly. ”

That Ryan cartoon is inaccurate, Ariel Scrag does not change the word “masturbating” to “menstruating” but fills her story with BOTH masturbation and menstruation. Now that’s what I call a bargain!

Schrag actually has lots of penises in her comics too.

I can’t stand Schrag. Looking at her art feels like sandpapering my eyeballs. Nonetheless, I applaud her and concede her worth.

Hi, Kim.

I share your certinty that there are — that there must be — definite gender biases in how critics approach autobio comics by men and women. Recognition of this type of bias is both new and old, similar to the ways in which women’s and men’s literary fiction is reviewed (see Katie Roiphe’s take on Ove Knausgaard’s “My Struggle,” 2014) or the way that literature by women has been situated via-à-vis the American canon (see Nina Baym’s “Melodrama’s of Beset Manhood,” 1981).

But while your general claims seem on target, each piece of evidence — or the accumulation of these pieces — seems to miss the mark. That was the point of my examples above, regarding Spiegelman, Brunetti, Brown, Heatley, etc. It was not a “gotcha” moment, finding the one example that contradicts your claim; rather, it was trying to show, using the biggest examples I could recall, that the language people use to criticize male autobio cartoonists is pretty much the same as the language people use, when they do, to criticize female autobio cartoonists: the language of self-absorption, of narcissism, of infantilism, of egotism, of privileged “whining.” The original post states and implies that this kind of reaction would be practically unthinkable for heroic male cartoonists. That does not seem to be the case. (Key parallel: Tyler is told she shouldn’t make her husband look bad; Spiegelman is told by Pekar and others that he shouldn’t make his father look bad.)

Perhaps one could say that the language with which we talk about the problems of autobio comics tends toward rhetoric as feminine: stop being so publicly emotional and self-obsessed (“Poor Gabrielle, has to talk to fans; suck it up”). Then again, self-obsession and egotism seems just as often a male-coded fault (“Poor Chester, can’t find a place for his dick; grow up”).

Now with your follow-up comment, my mind keeps reacting to your examples than to your overall picture. How is your chosen set of women cartoonists actually treated by the critical world? And I just don’t see it fr these particular women.

Lynda Barry: I honestly cannot recall a single negative review of her work, from her art shows, to her comics, to her teaching method. And we’re talking about the NY Times *and* The Comics Journal; Paris Review and CBR, Chute, et al., on the one hand, and Ware, et al., on the other.

I know less about the critical reaction to Davis, other than to report that is also seems to be uniformly positive, even from people (like me) who prefer her earlier, more freeform structures and styles. Wolk, Clough, and company all think she’s brilliant and funny, participating in the often feminist project of making “a new kind of comic out of experiences that never seemed like the stuff of art before.”

Allie Brosh’s reputation? I have no idea. But it seems telling that she’s both an NPR favorite and the subject of an appreciative writeup in “The American Conservative.” And if Rod Dreher isn’t going to provide a nice gender-skewed pull-quote, who will?

Maybe I just don’t know enough about the world of “comics criticism,” big or small. It’s honestly a world with which I interact only marginally, and it may be much bigger (and worse) than I know. But if that’s the case, then I need some pointers, showing me in more specificity how these biases and blindnesses get played out on the page and screen.

(P.S.: I think I’m even with Kailyn on the Seven review. After a weird start, it is practically a rave — trying to undermine the very attitudes expressed in the lede. Indeed, I think that was the *point* of the opening. Seven’s whole review is about the way that, for Bell, “autobiography is no more pure in its expression of reality than fiction.” That’s the import of the “why does she do this” questions — to show that they are the *wrong* questions.)

IDK, Peter, I feel you’re totally missing my point, though I may have made it poorly. The Tyler situation isn’t even remotely analogous to Spiegelman’s. And I don’t think Barry & Brosh have been critically panned at all. That’s not what I said, and in any case it’s beside the point–just as it’s beside the point that Seven’s review was positive.

My knowledge of crit is far from encyclopedic but I don’t think Chester Brown was mocked for being self-obsessed or egotistical. He was criticized for being a creep.

You’re right, Kim: we’re talking past each other, and I’m willing to take my full share of the blame. I do tend to grab a small thread and obsessively pull on it, sometimes losing track of the original point.

For example, I did misread what the Tyler anecdote was supposed to show. (You’re saying she was told she should not have published at all, because it would take some of the spotlight from Green?) On my behalf, if your point isn’t that women’s autobio is treated differently — and criticized in different, existential sorts of ways — then, yes, I have lost track of your real target.

So if you would like to show me some in-print examples of how Barry’s, Davis’s, and Brosh’s works are denied “legitimacy” or even the status of really being comics — much less being taken to task for reveling in womanly topics or emotions — then I would definitely be interested in seeing some of that silliness. Are the positive reviews heaped, deservedly, upon their work, showing substantive forms of gender bias? Are the raves say, in essence, this is awesome, but it’s not really comics? Where?

I am no great fan of the world of comics criticism per se, and don’t mind seeing it get its share of kicks. But right now, I just don’t see the data, even as I’m sympathetic to the claim.

Yrs,

Peter

You might be right about a double-standard for Gabrielle Bell and others, but I don’t care for all the sneering at dick-focused comics. They are kind of important to those of us who have them, so it’s understandable that autobiographical material would reflect that. And if it’s ridiculous to cannonize The Playboy or I Never Liked You because of their subject matter, would it be ridiculous to cannonize female cartoonists’ work about their sexuality? (You could actually say the same about Paying for It–if any of the hundreds of sex-worker memoirs out there are worth reading, then I think a sex-customer memoir is, too, at least in theory.) My guess is that people’s reactions to autobiographical art is largely determined by their own (often gender-based) experience. Someone who has gone through periods of angry, self-loathing depression will be more receptive to Ivan Brunetti’s early work, for example.

Hey Peter, at the risk of sounding dismissive, no, I’m not combing the data to back up my comment on a blog post, which itself contained several examples with the level of specificity you’re looking for. But let me ask you something. Do you think the comics world talks about What It Is, Picture This, and Hyperbole & A Half as autobio? I don’t. (Which is not to say that people don’t like those works. They do.) I don’t see a need to point to a review that explicitly calls those things “not comics.” It’s more in the way those works are talked about (or not talked about), if that makes sense.

Noah, as someone who probably reads a lot more comics crit than me or Peter, do you have any thoughts on this?

Re: Tyler, it wasn’t about stealing the spotlight. It was about the way she made a prominent beloved figure look bad. The feedback she received started after the first volume, I think, though it’s worth noting that evidently Green himself fought for her to never publish his part in that story at all. Really a fascinating story with so many levels of hypocrisy.

Jack, I Never Liked You is actually one of my favorite comics, and I wouldn’t classify it as the subgenre I’m talking about at all. Paying for It was really what I had in mind. (Haven’t read The Playboy.) Anyway you’ll notice I said there’s nothing wrong with that subgenre. I’m just making fun of it a little.

I actually dont’ read that much comics crit…but Suat does. I’ll ask if he wants to weigh in again….

Huh–it never occurred to me that What It Is and Picture This *weren’t* autobiography. Barry’s entire pedagogical project is so clearly rooted in her own life story; all of her recent stuff seems to be coming out of the retrospective analysis she started doing in One Hundred Demons.

With Barry, I’m mostly thinking about a few years ago when I was studying up on the category of autobio (and then later, when I read up on her specifically). She’s a revered figure in comics, but not autobiograhical comics…I think that’s the distinction I’m trying to make.

The Brosh thing is just a feeling. That said, a quick search brought up this Heidi MacDonald post, where she says that whether or not Brosh is really comics is an actual debate: http://comicsbeat.com/allie-brosh-is-probably-the-best-selling-cartoonist-of-the-year/

No, I see what you’re saying. One Hundred Demons is certainly a comic I encountered in the context of autobiography, but the subsequent work hasn’t really been characterized in that way at all–even though it all springs directly from her various childhood traumas … and is explicitly acknowledged as doing so by Barry in the texts.

Heidi’s post was the one I thought of when you mentioned Brosh.

I yield the floor to my smarters on all these issues. I know zilch about how what MacDonald calls the “comics industry” and “traditional comics outlets” thinks about anything. Maybe gender-bias emerges as one of many possible ways of expressing difficulty dealing with webcomics? (I’m guessing there are people out there, among the haters, who ask if Homestuck is “really” comics. They just won’t focus on his boy-ness.)

These issues don’t stand in isolation, Peter, and while this post is about gender, I don’t see it as the only force at work in the universe. People look down on web comics for sure (and you’ll find a similar sense of condescension towards work on the web across all of publishing, not just in comics). But it is worth noting that Hyperbole & A Half is in fact a book now, albeit one with terrible production values.

IMO there seem to be very narrow parameters for women’s work insofar as what “counts” as autobio…but even the stuff that counts (like Bell), there’s a weird set of criteria on which it is judged, especially for women whose subject is day-to-day life (as opposed to Big Issues like lesbianism or the Iranian Revolution). Is the work too serious? Is the work not serious enough? Men’s autobio is inherently serious, whether it’s about masturbation or the Holocaust.

Here’s a discussion of non-fiction prize-winners’ overall whiteness and maleness that seems relevant to this discussion, especially in its closing section on memoir (and Roz Chast): http://www.themillions.com/2014/10/is-there-no-gender-equity-in-nonfiction.html