I don’t know his name, just his origin. He starts out as a standard lab-coated scientist, arms stretched into a pair of wall-mounted containment gloves as he peers through an observation window at a glowing meteorite in his rubbery fingers. The protective wall is thick, which is why he survives the explosion. When he wakes in a hospital bed, he’s blind and armless. He’ll later grow phantom limbs—literally, their outlines are hazy with the meteorite’s mysterious energy—plus multi-dimensional vision, but first he has to face the horror of his ruined body.

The images look like comic book panels, drawn in Marvel house style c. 1980, but they exist only in my head. I’m remembering one of my adolescent daydreams. I never named my would-be superhero, so I’m retroactively dubbing him: Post-Traumatic Growth Man.

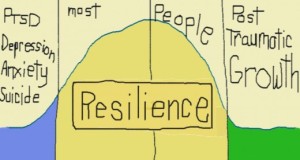

Jim Rendon introduced me to the term. Psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun coined it in 1995, and Rendon wrote about it in his New York Times Magazine “Post-Traumatic Stress’s Surprisingly Positive Flip Side.” Rendon is expanding the article into a book for Simon and Schuster now, and he emailed my university address looking for a professor willing to talk superheroes. He said he was hoping to learn more from me, but he’d already done his homework:

“It is the archetypal story of the hero who is forged through adversity by completing a life-threatening quest, suffering the loss of loved ones, surviving the destruction of home. Through survival of trauma, the hero becomes a great and selfless leader. And in popular culture narratives, nearly every comic book hero suffers some loss that spurs him or her to greatness–Batman, Spiderman, Superman, etc.”

I suggested he read Austin Grossman’s 2007 superhero novel Soon I Will Be Invincible. Grossman told an interviewer that trauma is “the motivating, defining attribute of the superhero. I guess it’s kind of the hopeful element of superhero comics; the idea of the trauma that shapes you is not just pain; it’s also the thing that makes you special . . . .” Video game designer Jane McGonigal explored that same “hopeful element” when creating “SuperBetter” in which her superheroic avatar “Jane the Concussion Slayer” helped her overcome a real-life injury. But, Rendon asked me, where did this defining superhero attribute come from?

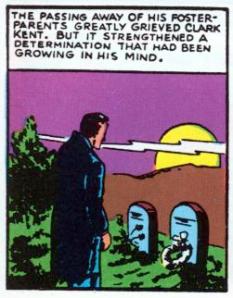

Well, Nietzsche, the man who gave us the ubermensch, said it first: “what does not kill me makes me stronger.” Jerry Siegel borrowed more than just the name. Look at Superman No. 1 and there’s Clark staring at a pair of gravestones: “The passing away of his foster-parents greatly grieved Clark Kent. But it strengthened a determination that had been growing in his mind.” Bruce Wayne’s superheroic response to his parents’ murders is even more overt: “And I swear by the spirits of my parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals.”

But both origins were add-ons. Batman patrolled Detective Comics for six issues before an editor demanded Bob Kane provide an explanation. Superman No. 1 was a reprint of Action Comics adventures with an expanded origin that retconned Clark’s foster parents. In the first one-page origin, a passing motorist drops the alien baby at an orphanage. All those traumatically dead parents were afterthoughts.

Before the late 30s, superheroes didn’t know much about Post-Traumatic Growth. Doc Savage, the Shadow, Zorro, the Gray Seal, the Scarlet Pimpernel, all their do-goodery was equal parts altruism and thrill-seeking. Trauma didn’t fully hit the pulps till 1939, when the Black Bat got a face full of acid, and the Avenger’s family perished in a plane crash. Batman and Superman lost their ad hoc parents the same year, and soon almost every Golden Age hero—Green Arrow, the Flash, Plastic Man—had to have his own special tale of superhuman recovery.

U.S. Army recruits wouldn’t ship out for three years, but war was raging in Europe, and the comics are a surprisingly perceptive flip side to front page headlines. There are also some PTG tales earlier in the decade (the Domino Lady’s dad was murdered by gangsters), so Rendon wondered aloud on the phone whether the trope might be a national recovery tale: the U.S. rising heroically from its Depression. I like both those readings, but I don’t think superheroes really start growing, post-traumatically or otherwise, till the 60s. Stan Lee knew how to make a hero suffer.

Most unitard-wearers slap a defining symbol on their chest, a bit of iconic lip service to that supposedly life-transforming trauma, but Jack Kirby didn’t even draw a costume for the Thing. His body is his on-going disaster, one that extends well beyond the frames of this origin story. Peter Parker, like most Marvelites, should have died of radiation poisoning, but it’s the mental anguish of allowing his uncle to be murdered that spurs him to atonement. The crippled Donald Blake is just wobbling through his life until he finds a cane that transforms him into a god of thunder. After Tony Stark trips a jungle booby-trap (“Impossible to operate! Cannot live longer than a week!), he manufactures “a mighty electronic body, to keep [his] heart beating after the shrapnel reaches it!” For Doctor Strange’s fourth issue, Lee and Steve Ditko retconned a career-ending car accident that turned the wealthy neurosurgeon into a penniless vagabond—and then the Sorcerer Supreme.

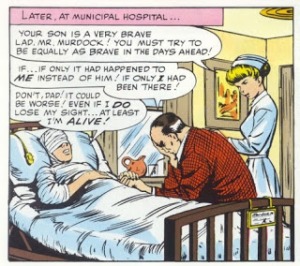

By 1964, Lee had exhausted his creative reserves, introducing his last but most post-traumatic superhero. After saving a blind man in a crosswalk, young Matt Murdock lies in a hospital bed, his head heavily bandaged after being struck by a radioactive cylinder that fell from the speeding truck.

NURSE: “Your son is a very brave lad, Mr. Murdock! You must try to be as equally brave in the days ahead!

DAD: “If . . . if only it had happened to ME instead of him!”

MATT: “Don’t, Dad! It could be worse! Even if I DO lose my sight . . . at least I’m ALIVE!”

That surprisingly positive attitude pays off two panels later. “I don’t get it!” says the now super-athletic Matt. “I seem able to do everything lots betters than before . . . even without my sight!” Throw in “razor sharp” senses and “built-in radar” and Daredevil is the PTG poster boy—but only because he remains blind. He’s why Grossman sees “the larger theme of superhero life as trauma and recovery from trauma; the way superpowers arise in trauma to the body that one never quite gets over. The trauma impresses itself onto the body but also leads to a hyperfunctioning of the body.”

That larger theme impressed itself on me too. My nameless but mutilated scientist and his eventually phantom-limbed persona were the unexamined DNA of Bronze Age comics. I absorbed the trope like radiation, and it filtered back out through my adolescent daydreams. And now Jim Rendon is studying it under his journalistic microscope. His book, Upside: Transforming Trauma into Growth, is due out in 2015–just in time for Daredevil’s premiere on Netflix. I’m looking forward to both.

Another recent book that talks about this is José Alaniz’s Death, Disability, and the Superhero. I wrote about it here; it’s quite good.

Chris, wouldn’t the Count of Monte Cristo qualify as a PTG superhero/villain?

And hey, what about PTG supervillains? Dr Doom.The Joker.Doc Ock.

Thanks, Noah–someone else just mentioned Alaniz’s book to me too. I clearly need to read it.

And, Alex, yes on the Count. In fact, I think he may be the ur-trope, the first superhero who is in someone way wronged and so responds with his transformation and mission. That “wronging” is originally some kind of aristocratic disinheritance (The Clansmen, Scarlet Pimpernel), which evolves into being physically “wronged.” And villains are the same, but instead of PTG, I’d say they suffer PTI, post-traumatic isolation and seek anti-social revenge.

Spring-Heeled Jack was wrongly disinherited, too. And I found that same theme of disinheritance running through years of dime-novel westerns.

In fact, isn’t it also the theme of 19th-century interpretations of Robin Hood (Scott, Dumas, et al?)

Perhaps it reflects that century’s unease at the rise of industrial capitalism in parallel to the slow eclipse of traditonal class privilege…

Fear of the egalitarianism of the American and French revolutions coupled with further corrosion of the aristocracy by the Darwinistic threat of working class degenerates and upper class degeneration. The trend gives birth to the eugenics superhero.

Is it significant that the Marvel creators of the sixties were survivors of the Great Depression and World War II, yet they were separated from those nationally shared traumas by more than fifteen years? Did the maturity of mid-life, the processing time, or just the temporal distance give them the perspective and the ability to see what experiences like this can do? Disability, physical mutilation, the death of loved ones — aren’t these echoes of the war? Aren’t Peter Parker’s constant concerns about money and his inability to care for the woman who raised him just a reiteration of the average American’s experience in the thirties?

Hardship makes heroes — and sometimes villains. I think Lee, Kirby, and Ditko had a visceral understanding of these phenomena, based partly on direct experience.

Parker’s hard times seems like a mildly hidden account of the immigrant experience, I often thought.

Sure. Lee and Kirby were the children of immigrants. Ditko, as the grandson of immigrants, was the blue-blood of the bunch. The Depression is still relevant, though. Their ages in 1933 were 11, 16, and 6, respectively. Ditko and Kirby almost perfectly bracket the age range most deeply affected by it as children.

I’ve never really thought about those experiences and the almost deterministic impact they must have had on the Marvel Age of comics. How could they not write about imperfect, hard luck heroes? That described half the people they knew! How did it take them that long to start? I guess they really were trapped by convention and what their publisher thought would sell.

Did we also start seeing flawed, but idealistic heroes who were the products of great loss in other media at this time? Who were the heroes of television, novels, and the silver screen in 1962? If it took those media time to catch up, then why? There’s a research paper in this — maybe a thesis. Tell your students I’d be thrilled by a brief mention in the acknowledgments section.

Interestingly, Kanigher, Kubert, and Schwartz were all born in 1915, according to Wikipedia, so they were eighteen in 1933 (according to Wikipedia). Schwartz was reportedly the son of immigrants, but my feeble search reveals no definitive answer to that question for K & K.

Good question about other early 60s hero types. My first tentative guess is no. James Bond and John Wayne and Aragorn don’t look much like Lee’s hard-luck heroes to me. I think that fact that Lee was trying to quit the superhero genre may be significant since it seemed to allow him to push harder against those conventions.

So, continuing the hypothesis, Golden Age heroes and heroines were mostly bland, ideal men and women of their time who had it all together. They were emotionally well-adjusted, they conformed to society’s expectations, and they always knew the right thing to do. No, scratch that. That’s not giving enough credit to the full spectrum of Golden Age characters, in which weirdness and dysfunction were amply represented. But it was certainly true of the DC icons that survived Kefauver and Wertham to be recast in silver by Schwartz and crew. That was who the real heroes were supposed to be for that generation — Doc Savage and Sgt. Preston of the Yukon, Alan Scott and Jay Garrick. Even the strangeness of The Shadow was tempered by good, old Lamont Cranston, or later Bruce Wayne.

But the next wave of kids didn’t buy it. They knew the truth. Nobody’s that well-adjusted. Everybody has some weakness or flaw, some guilt or shame. Hoover was the best qualified man to run the country, and he couldn’t figure out how to prevent economic collapse or even stop it once it started. The statesmen let the fascists come to power, build massive armies, and then start conquering. The generals and admirals let us be caught with our pants down at Pearl Harbor and led us to disaster at Kasserine Pass. The best leader we could find to put our hope in was (in the terminology of the day) a cripple in a wheelchair!

The war experiences of men like Kirby must have confirmed the hypocrisy. How many men did he see lose their composure and make bad decisions out of frustration, rage, or fear? How many of them were officers he was supposed to trust with the mission and his life?

So they knew it was all a lie. Even the guys who seemed like real life DC heroes weren’t really Justice Society material. Superscientists like Oppenheimer had amazing achievements, but the consequences haunted them the rest of their lives. Inventor playboys like Howard Hughes must have really had holes in their heart that women and booze couldn’t fill. All the creators had to do to turn the comic book world on its head was tell the truth.

Good point, Chris. I suspect that Marvel Comics were at or near the leading edge of the deconstruction that later enabled Clint Eastwood’s spaghetti western protagonists challenge the Duke.

Chris:

“Fear of the egalitarianism of the American and French revolutions coupled with further corrosion of the aristocracy by the Darwinistic threat of working class degenerates and upper class degeneration. The trend gives birth to the eugenics superhero.”

That Darwinistic threat is most beautifully expressed in H.G.Wells’ The Time Machine with its Morlocks and Eloi — with no superhero in sight (although Wells, of course, was a passionate champion of eugenics.)