This first appeared on Splice Today.

_______

According to Godwin’s Law, whoever compares their opponents to Hitler first in an online argument loses. Maybe it’s time to develop a similar rule of thumb for comparisons to chattel slavery. Stop Patriarchy an activist group which presents itself as fighting for reproductive rights in Texas has been especially busy recently in promulgating poorly thought through slavery comparisons, as in this tweet. “BREAK THE CHAINS! BREAK! BREAK! THE CHAINS! IF WOMEN DON’T HAVE RIGHTS WE ARE NOTHING BUT SLAVES.” Just to make sure you don’t think it’s a one-off mistake, their twitter bio helpfully declares, “End Pornography & Patriarchy: The Enslavement and Degradation of Women!”

According to Godwin’s Law, whoever compares their opponents to Hitler first in an online argument loses. Maybe it’s time to develop a similar rule of thumb for comparisons to chattel slavery. Stop Patriarchy an activist group which presents itself as fighting for reproductive rights in Texas has been especially busy recently in promulgating poorly thought through slavery comparisons, as in this tweet. “BREAK THE CHAINS! BREAK! BREAK! THE CHAINS! IF WOMEN DON’T HAVE RIGHTS WE ARE NOTHING BUT SLAVES.” Just to make sure you don’t think it’s a one-off mistake, their twitter bio helpfully declares, “End Pornography & Patriarchy: The Enslavement and Degradation of Women!”

Local Texas anti-abortion groups have responded by fervently telling Stop Patriarchy to cut it out and go away. The all caps declamations do make you wonder though; why on earth does Stop Patriarchy think this is a good idea? What exactly is the comparison supposed to accomplish? What is appealing in taking this other, different oppression and casting it in the language of slavery? Is it just a particularly clumsy way to say, “curtailing reproductive rights is really bad”? Or what?

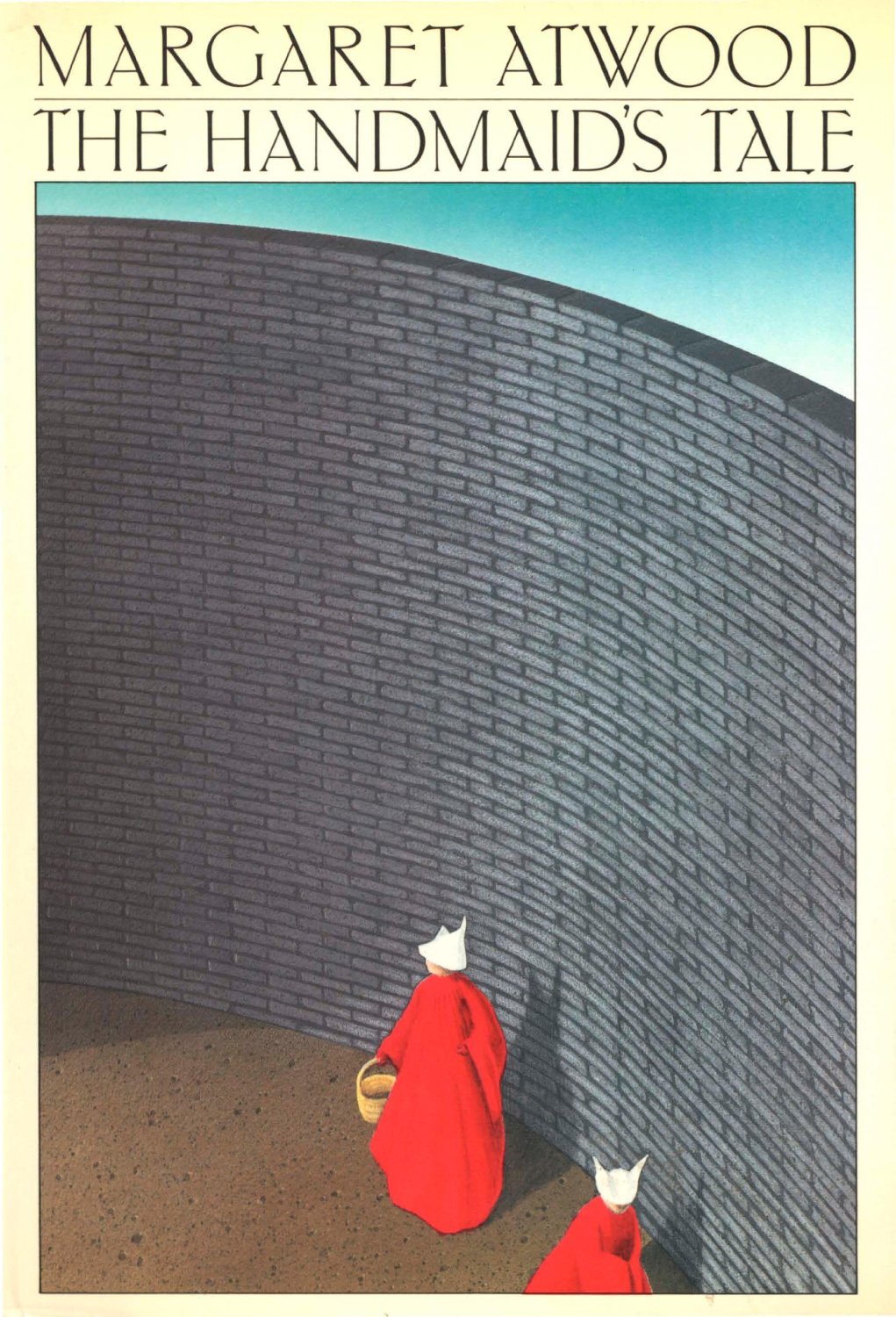

One way to answer that question is to consider one of the most famous feminist novels of the last thirty years: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood’s novel, published in 1985, is set in a dystopian near future in which right-wing family-values religious fanatics have taken control of the United States. The nameless protagonist and narrator was a librarian prior to the coup. The new rulers stripped her of her money, her profession, and her child and marriage, the last of which is considered invalid since her husband was previously divorced. She is forced by the new government of Gilead to become a Handmaid, assigned to various important men as a kind of official mistress, in hopes that she will bear them children — an imperative since chemical and radioactive pollution has sterilized much of the population.

The Handmaid’s Tale clearly owes a debt to other totalitarian dystopias, most notably 1984. But it also borrows liberally from the experiences of non-white women. In fact, the novel’s horror is basically a nightmare vision in which white, college-educated women like Atwood are forced to undergo the experiences of women of color.

This transposition is not especially subtle, nor meant to be. Handmaids wear red, full-body coverings and veils which reference the burqa. In case the parallel isn’t sufficiently obvious, Atwood has her narrator directly compare the Handmaids waiting to perform their procreative duties to “paintings of harems, fat women lolling on divans, turbans on their heads, or velvet caps, being fanned with peacock tails, a eunuch in the background standing guard.” The narrator has been teleported into an Orientalist fever dream, the irony only emphasized early in the novel by a group of modern, Japanese tourists, who stare at the debased Occidental women just as Westerners stereotypically stare at the debased women of the Orient. The stigma against Islam is leveraged along with, and blurs into, the stigma against prostitutes; the horror here is that middle-class, college-educated white women will be forced into the position of sex workers.

Slave experiences are appropriated with similar bluntness. The network that secretly ferrets Handmaid refugees over the border to Canada in the novel is called, with painful obliviousness, the Underground Femaleroad. We learn, in an aside, that the regime hates the song “Amazing Grace” — originally an anti-slavery song. It’s reference to “freedom” has been repurposed here to apply to Gilead’s gender inequities. The specific oppressions the Handmaids face also seem lifted from slave experience — they have their children taken from them; they are not allowed to read; they need passes to go out; if they violate any of innumerable rules, they are publicly hanged. The tension between white mistresses and black women on slave plantations is even reproduced; the narrator’s Commander wants to see her outside of the proscribed procreation ceremony. She of course can’t refuse — even when she finds out it provokes the commander’s wife to dangerous sexual jealousy. This is a familiar dynamic from any number of slave narratives (12 Years a Slave is a high-profile recent example) with the one difference that here, not just the oppressor, but the oppressed, is white.

Atwood is hardly the first science-fiction author to create a white future from elements of past non-white oppression. As I’ve written before , this kind of reversal is central to the genre; H.G. Wells, explicitly compares the invasion of the Martians in The War of the Worlds to European colonization of Tasmania. Wells explicitly presents this parallel as a moral lesson; he asks Europeans to imagine themselves in the position of the colonized, and to think about how that would feel. You could argue, perhaps, that Atwood is doing something similar — that she’s trying to get white people, and particularly white women, to imagine themselves in the position of non-white women, and to be more appreciative of and sympathetic to their struggles. You could see The Handmaid’s Tale as analogous to Orange Is The New Black, where a white women is a convenient point of entry to focus on and think about the lives of non-white women.

Orange Is the New Black actually includes Black and Latina women as characters, though.The Handmaid’s Tale emphatically does not. The book does say that the Gilead regime is very racist, but the one direct mention of black people in the book is an assertion of their erasure. The narrator sees a news report which declares that “Resettlement of the Children of Ham is continuing on schedule.” Here Atwood and Gilead seem almost to be in cahoots, resettling black people somewhere else, so that we can focus, untroubled by competing trauma, on the oppression of white people.

Atwood and Gilead are in cahoots in some sense; Atwood created Gilead. You can hear an echo of the writer’s thoughts, perhaps, in Moira, the narrator’s radical lesbian friend, who is not shocked by the Gilead takeover. Instead, the narrator says, “In some strange way [Moira] was gleeful, as if this was what she’d been expecting for some time and now she’d been proven right.” The Handmaid’s Tale presents a world in which white middle-class women are violently oppressed by Christian religious fanatics. As such, it is not just a dystopia, but a kind of utopia, the function of which, as Moira says, is to prove a certain kind of feminist vision right.

That vision is one in which women — and effectively white women — contain all oppressions within themselves. The Handmaid’s Tale is a dream of vaunting, guiltless suffering. Maybe that’s why Stop Patriarchy finds the slavery metaphor so appealing as well. Using slavery as a comparison is not just an intensifier, but a way to erase a complicated, uncomfortable history in which the oppressed can also sometimes be oppressors.

And now it’s coming to comics:

http://groupthink.jezebel.com/the-handmaids-tale-graphic-novel-1630506060

“Atwood and Gilead are in cahoots in some sense; Atwood created Gilead.”

So are the writers of all those what-if-Nazis-won-the-war, alternate history SF novels engaging in Holocaust wish-fulfillment? Or can fiction legitimately create scenarios that follow the logic of racist, sexist agendas? I think you’re employing a really problematic method of implication-by-creation; the author wrote it, so she must desire it. Yes, I think that religious fundamentalists in this country are trying to create something like Gilead.

I think it depends. I think dystopias are often utopias in the sense that they’re set up to prove the writer correct. 1984 works like this, as just one example. The Hunger Games too as well. Dystopias are concern trolling, basically. It’s part of the genre.

One interesting place this doesn’t quite happen is in Philip K. Dick’s “The Man In the High Castle.” The meta-fictional aspects undermine the reality of the alternate history, so you end up with more a questioning of possibilities rather than a harangue. Marge Piercy’s A Woman on the Edge of Time (a much, much better novel than the Handmaid’s Tale) does this as well — and so to some degree does Ursula K. Le Guin’s the Dispossessed. So…good writers are aware of, and question, their impulse to dystopia I think. The Handmaid’s Tale is simplistic and not very thoughtful, unfortunately.

Well, they question their impulse to utopia as well, don’t they? For example, in The Dispossessed we’re shown that not all is hunky-dory in the Anarchist utopia supposedly superior to the capitalistic dystopia depicted.

The Man in the High Castle also has its ambiguities…the subjugated occupants of the western USA don’t have such a bad time of it under Japanese rule. Even 1984 isn’t always ideologically clear-cut: the Proles seem to be fairly well-off; and Winston Smith is trapped by O’Brian into admitting he would be willing to commit atrocities for his cause (specifically, to throw acid into a child’s face.)

Utopias/dystopias generally function as ‘proofs of concept’ for the author’s hypothetical ideal world; see More’s Utopia, Bellamy’s Looking Backwards, H.G.Wells’ Men Like Gods, Theodore Sturgeon’s Venus plus X; or satires like the various realms encountered by Gulliver (Swift), or Pohl and Kornbluth’s The Space Merchants.

These thought-experiments may be entertaining or bemusing, but unless they contain the seed of their own contestation they fall someting short of literature.

Isn’t there a long tradition of white feminists using slavery metaphors, which has always annoyed black women?

I haven’t read The Handmaid’s Tale, but this essay reminded me of Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, in which Charles Lindberg beats out FDR to become President, America becomes anti-Semitic, the U.S. government sucks up to Hitler, pogroms start breaking out, etc. On the one hand, you can see the book as Roth taking the real-life institutional anti-Semitism of the 40s (which really did affect his family) a couple of steps further. But it also seemed like his worst nightmare was that 40s-era America could treat Jews as badly as it actually did treat blacks.

Jack has two good points. The first reflects the longtime connection between the rhetoric of abolitionism and that of women’s emancipation — and thus the link of woman and slave — from the very beginning of both movements in the US and Britain. And as Lepore’s Wonder Woman book has indicated, these connections continued into the 20th century (including the work of H.G. Peter). If Atwood is paving new ground, it is only in using the rhetoric really, really badly, even as she continues in a fairly long-standing tradition.

And for a thorough examination and evisceration of Roth’s Plot Against America, see Walter Benn Michaels’ “Plots Against America: Neoliberalism and Antiracism”: “So, part of the book’s power derives from its realism, the fact that it feels like the truth,… while another part derives from the fact that, of course, it’s not true: it didn’t happen here. And both these fact — the fact that it could have happened here and the fact that it didn’t — are given additional power by a third fact, the fact that, of course, it did happen here, only not to the Jews. . . . Why should we be outraged by what didn’t happen rather than outraged by what did?”

Philip Roth…ugh. A writer I like even less than Margaret Atwood.

It really pisses me off that The Handmaid’s Tale has replaced Margaret Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time as the feminist sf novel everyone knows. Piercy’s book is much, much more thoughtful, not least in having a protagonist who isn’t white, and in emphasizing the ways in which sexism and racism intertwine. It’s a much more honest, much more insightful, vastly better written book. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that all those reasons have caused people to turn instead to Atwood’s whitewashed, simplistic parable.

Three-times true. ^^

I wasn’t aware that feminists compared themselves so explicitly to abolitionists. The pro-life movement does, also. The comparison is based on the fact that both movements derive much of their ideology, membership, and zeal from segments of the Christian church, and that both advocate on behalf of those deemed less than fully human.

Noah: who is Atwood “concern trolling”? I don’t think anybody could even perceive her as supporting the kind of regime she writes about… so are you saying she’s pretending to be feminist, but really anti-feminist? It’s a leap even from your arguments to that conclusion.

Pointing out that there’s an element of vindication in Atwood’s scenario isn’t a very strong criticism in itself, of The Handmaid’s Tale or 1984, and Atwood was already ahead of you in any case. I don’t agree that postmodern metafictional conceits are sufficient to redeem drama from being a cathartic pornography of violence and suffering—you need to narrow your sights a little bit to find a problem with Atwood—but the character Moira’s reaction, even as you describe it, functions as exactly the kind of reflexivity and self-consciousness you’re calling for. Why not give Atwood credit for it? Or if you don’t want to, what do you think she was trying to accomplish there?

If feminists invoke slavery, I don’t think they’re offending against the sanctity of black history. I think these comparisons need to be taken case by case, not categorically inveighed against. Howard Cruse’s graphic novel Stuck Rubber Baby paralleled the 1960s civil rights struggle against segregation with a gay man’s coming out narrative, and I think it would be ridiculously narrow and short-sighted to take offense at that parallel, even though there are major differences. The point is these causes are allied.

Haven’t read Cruse. Feminism and civil rights have not always been allied, though. Many feminists were really racist. That’s the point of the piece. The novel creates a situation in which white women’s experiences are seamlessly mapped onto the experiences of women of color. That’s false, and it’s a falsehood that has frequently been used as leverage against women of color (Margaret Sanger’s support for eugenics is perhaps the most obvious example. Not coincidentally, Piercy’s novel is a criticism of eugenics.)

Dystopias are concern trolling in the sense that they’re inveighing against evil thing x while reveling in evil thing x.

I don’t think Moira’s reaction is much of a critique. A one-off one-liner from a minor character; it doesn’t really work to undermine the logic of the novel. Again, Piercy is a useful comparison; her vision of utopia is much more thoroughly questioned, not least in her very conflicted presentation of the need for, and evil of, revolutionary violence.

I think the word you want is “prescribed,” not “proscribed,” as in “prescribed procreation ceremony.”

American slavery is unique, though. Every other kind of slavery that has ever existed has been based on the slave’s war-chattel status rather than on the slave’s race, and the slave usually had some kind of a shot at freedom at some point in time; there might be a time limit on their enslavement, or there might be a prescribed (there’s that word again) set of behaviors they were supposed to perform in order to “earn” their freedom. Slavery was not normally a lifelong proposition.

(This is why I am unmoved by arguments that Native Americans kept slaves, implying that they were no better than white people and therefore deserved to lose their lands and cultures. Natives didn’t enslave the way whites did.)

Any road, enslavement is only a racial issue in the United States because enslavement was a racial issue in the United States. It isn’t a racial issue anywhere else.

And you fail to engage intersectionality and to understand that whites DO oppress whites RIGHT NOW, never mind in a dystopian novel. If you have money and status, you’re golden. If you don’t have money and status, you’re shit and upper-class whites can do anything they want to do to you.

There are white homeless people dying in the streets right now. If you haven’t been outside in a few days, it’s REALLY cold out there.

None of this is to diminish black American history. But let’s not be so simplistic, especially when we are trying to come off as intellectual.

And until someone has used your reproductive capacity to diminish your life and your future prospects, don’t you dare lecture feminist activists about what metaphors we are supposed to use. Having money taken out of your account every month for child support pales in comparison.

I think you’re a smart guy and very observant, but damn.

As I mentioned in the piece, many feminist writers, especially black feminist writers, are quite angry at the use of slavery metaphors. So, I think attributing that anger to the fact that I’m male seems like it doesn’t really address the many women (and again, many black women) who feel like it’s a problem.

It’s not intersectional to conflate different experiences and say that someone is oppressed so they must be oppressed the same way as everyone else. Intersectional analysis is supposed to take account of the way different oppressions are different. Homelessness is very different from slavery; the two aren’t congruent (though of course homelessness is disproportionately black in the U.S. because of a history that goes back to slavery.) Further, the handmaid in Atwood’s book is identified specifically as white, college-educated, and middle class. People like that can suffer injustice and oppression, of course. But pretending that their experiences are usefully compared to the experiences of slaves is I think really reductive and offensive.

Black women actually talk a lot about the ways in which white feminism presents gendered oppression as a universal experience, appropriating black women’s experiences while often simultaneously telling black women to be quiet, or silencing their stories. That’s what the #solidarityisforwhitewomen hashtag was about. I think it fits The Handmaid’s Tale painfully well.

As Noah points out, Dana doesn’t seem to know what “intersectional” means.

It should also be noted that s/he also seems to know less than nothing about slavery in the ancient Mediterranean, slavery in the Caribbean and Central and South America, or even slavery in the United States.

Dana, parenthood has enriched my life, not diminished it, and I think the mothers I know would say the same thing — even those whose pregnancies were unplanned. Admittedly, it does narrow one’s options, but putting the child up for adoption is one option that parents have. Finally, real fatherhood is much, much more than a child support check. I understand that many men don’t even contribute the check, but let’s not act like that’s even within sight of the standard.

John, I am more or less with Dana on that. Whatever the ideal may be, the fact is many men don’t even bother with the child support check. And while you may feel parenthood enriches your life (and I certainly do), that doesn’t mean that you should get to decide reproductive choices for other folks.

Noah, we’ve been down this road before. We agree that people should make their own reproductive choices. Our difference is that at the point of conception, I believe the choice has been made and reproduction has occurred.

My only new point was about the characterization of parenthood as something tragic, and fatherhood as primarily a financial obligation. I don’t think you’re with Dana on either one of those. For what it’s worth (and I apologize if association with me hurts your case), but I’m with you on the post above. I do not think being legally required to carry a pregnancy to term is comparable to any society’s version of slavery. My pro-life views aside, that still seems inappropriately hyperbolic.