Adrian Tomine gives good interview. He’s thoughtful and smart, which are two different things, and self-deprecating in a way that isn’t designed to mask false modesty. He’s doing a lot of press right now, and in each conversation he offers something new. When I read his Q&As, I’m always struck by how low-key and likeable and honest he seems. Maybe it’s me and maybe it’s comics (and definitely it’s the format of Giving an Interview, which makes it near impossible to not sound like a self-serious asshole), but cartoonists rarely strike me in this way. If I were to overhear any given interview (including the ones I’ve conducted) as a conversation in a bar, I’d probably think those people sound like dicks.

Killing and Dying was my first time reading Tomine, and I had high expectations. Part of that is his likeability and part is his legend as indie comics’ most sensitive son. For every man in Tomine’s audience who finds the phrase “graphic novel” problematic (lol), there’s a sap like me who thinks it’s adorable that he was drawing love comics at age 15. An unhappy teenager who has grown into a vaguely anxious and uncomfortable adult—this is a figure who speaks to me and my struggle. Many of those art comics guys in the 40+ crowd—Chris Ware, Seth, Chester Brown—are eccentric and cold sort of alien beings, from my vantage. Tomine is more relatable somehow. I can see myself in him.

But, as it turns out, I do not see myself in his stories. In fact, I don’t see anything resembling a real woman in his most recent work. The world of Killing and Dying is filled only with men and the shells of the women who orbit them. Each of these women is characterized, if at all, by the degree of ambivalence with which she loves some sad fucked-up failure of a dude.

The first story, “A Brief History of the Art Form Known as ‘Hortisculpture,’” is an allegory about comics in which a dutiful wife and loving daughter try to support the bumbling man of their house, an artist. His journey is in coming to terms with his failure. Along the way, he makes things and destroys things. We know about his job and his hobby and how those things sustain and haunt him in turns. His wife and daughter, in sharp contrast, are not autonomous beings in the world of this comic. Their inner lives, their conversations, and their actions all center on the male protagonist. They support him, or worry about him, or feel embarrassed by him. They exist only in proximity to his dim sun.

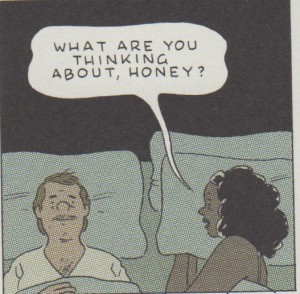

“What are you thinking about, honey? It’s important that you tell me because I don’t have any of my own stuff.”

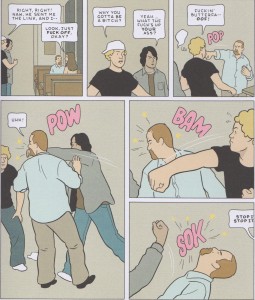

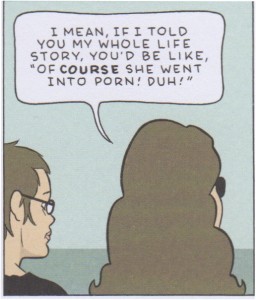

Similarly, “Go Owls” is the story of a pathetic man—Barry, a drug dealer—and his nameless female companion. Barry is a volatile person who is abusive and tender in turns. Tomine gives him both a backstory and a future. Barry even has an existence (such as it is) outside of the presence of his girlfriend, playing guitar and selling marijuana to soccer moms. Jane Doe, on the other hand, never appears on a page without Barry. Her long bouts of passivity are only punctuated by displays of one-upmanship when Barry says something dumb. (Even her cleverness exists only in analogy.) Otherwise the full extent of her characterization is a substance abuse problem and a sister she mentions in passing. Tomine’s subtle, expressive drawing clearly broadcasts her inner life, which seems to consist wholly of her contempt for Barry (unless you count her contempt for herself, which I don’t, since there is no “herself.”).

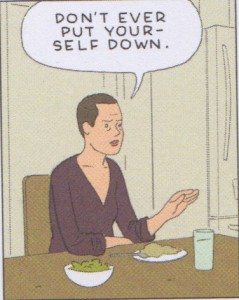

“Listen, babe. We don’t need your story, babe. You’re a babe, babe. And that’s your thing.”

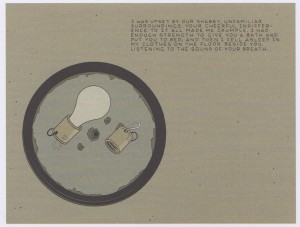

“Translated, from the Japanese,” the shortest and strongest story by a mile, is a sort of letter from a ghost to her son. From her innermost feelings to her outward actions, every detail this mother reports traces back to one of three guys in the story—her son, her estranged husband, or a college professor she happens to sit next to on a plane. You can pin all her thoughts and feelings on those three dudes. The only thing that gives the piece any depth is the suggestion that her story is a relic from a past from which she has since moved on. The emotional timbre of the story is that of a journal entry—and yet it’s addressed to the narrator’s son. Why?

“You fell asleep, and then so did I. It’s almost as though when you close your eyes, I simply cease to exist.”

“Killing and Dying,” the central story, also involves an absent woman. Other reviewers seem to think the story is about a teenage girl, but it’s not. It’s about the struggle of her tortured father. My god, this man is such a cliché.

Everyone knows dads don’t cook.

And so is his wife.

Moms just believe in you so hard. That’s literally all they do (in this story).

This man’s ~j o u r n e y~ is about learning to let his daughter Jesse make her own mistakes. Though Jesse has more grace and maturity than her father, she doesn’t develop over the course of the story in a meaningful way. And the wife, well, she doesn’t have much of a journey either. I don’t want to spoil anything, but let’s just say that on top of being a cliché, she’s also a sort of gimmick/technical device.

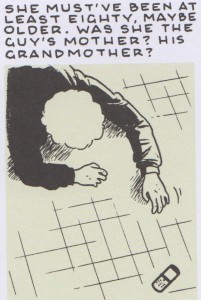

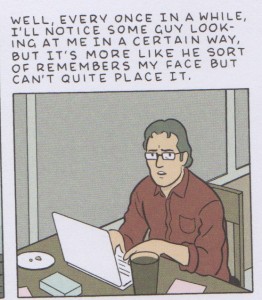

I don’t have much to say about the last story, “Intruders,” which is about a loner. But it’s telling that even its female “extras” are conceptualized in terms of the dudes to whom they belong.

It’s not that the artist hates women. There’s no doubt that, in the Tomine universe, women are superior to men. The ladies of Killing and Dying are, for the most part, hotter, smarter, more patient, more successful, less self-absorbed, less ridiculous, and better adjusted than their male counterparts. Even when they’re flawed (like the nameless woman in “Go Owls,” or Jesse, the teenage comedienne), they’re sympathetic because of the unpleasant, limited man that it is their lot in life to endure.

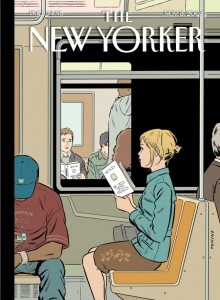

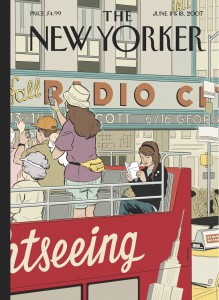

I haven’t read Tomine’s other work (and I’m not sure I will), but I’ll wager his whole thing is idealizing women. I think about his iconic New Yorker cover, which takes one of the most solitary acts in all of womanhood—reading on public transportation—and turns it into a sort of love story. Or his similar, if lesser known, cover, which fetishizes a teenage girl reading Catcher in the Rye. Tomine’s gaze is focused on their books, not their boobs, but it still represents the point of view of someone who imagines the stares a woman receives to be little romances that unfold throughout her day. I guess from his point of view, it probably feels that way. Wistful. Idyllic. Not creepy.

When Tomine does touch on the subject of harassment, as he does in his story about a nameless college student who looks just like an Internet porn star (“Amber Sweet”), its effects are visited most vividly upon—wait for it—a man.

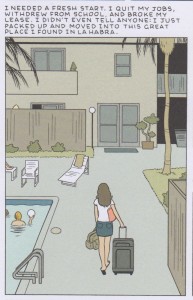

Unable to find a guy in college who will date her, Jane Doe quits her life and moves somewhere new.

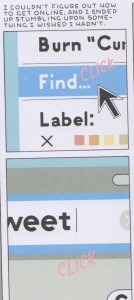

This story is broad to the point of absurdity. Perhaps to some extent that’s on purpose. Maybe Jane Doe is in fact Amber Sweet and that’s why her life story—a lie she’s telling a new love interest—itself sounds like a half-baked porn plot. Certainly she’s an unreliable narrator, as we see in a panel where her description of “stumbling upon something” doesn’t match the deliberate search we see her carry out in the panels.

But riddle me this: How come Amber sees harassment as a choice that she made for herself, rather than choices made by the men who harass her?

Why is Amber’s backstory a tired cliché?

And, above all, how is it that every single man in the United States of America seems to watch the exact same Internet porn?

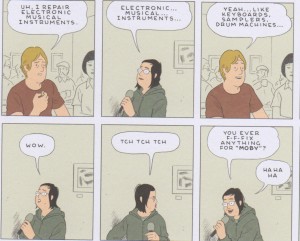

These are the kind of problems you run into when your character is a tool in your parable about fraught identity instead of a fully imagined person. And the same lack of attention to detail can be seen across Tomine’s female characters, who never quite ring true. Witness Jesse, a teenager whose top-of-mind pop culture references include Moby.

MOBY. I just can’t even.

Despite these missteps, Tomine’s talent is plain. There are quiet moments of real insight, like when he writes about how your neighbors on a long flight transform back into strangers after you deplane. He has a natural ear for dialogue. His facility with his pen across multiple styles (which he employs to great effect throughout the collection) really can’t be overstated. And his palette is flawless, demonstrating a masterful use of color that surpasses even Ware’s.

Still, even if you adjust for this industry’s tendency to make overblown declarations about the significance of any given project, Killing and Dying has been heaped with unearned praise. The most reserved review I’ve seen named Tomine “one of the most significant artists working in a young, fluid, thrilling genre.” The Globe and Mail praised his “mastery as a writer” and “peerless” cartooning skills. “A deft, deadpan masterpiece,” raved Publisher’s Weekly. The Kirkus Review straight up referred to him as a wizard.

The truth is that Killing and Dying is not the work of a wizard or a genius or even someone at the top of his game. Adrian Tomine is very talented, yes—but he’s also a writer with bald limitations. I don’t want or need to see myself in every comic ever written, nor do I think that every story requires a round female character. But an entire collection of stories in which women are props defined by their feelings for broken men? That is pathologically bad writing.

Whether it’s autobio or ciphers in fiction, art comics are packed with male protagonists obsessed with their own loserdom. I think too often they hate themselves for the wrong reasons. It bothers me how often work that’s praised for its “unflinching honesty” is drawn by men who are, to my eye, hopelessly blind.

Your criticisms of Tomine echo mine. I’ve been half paying attention to him for a long time hoping he’ll get better, I guess. For whatever reason I stay interested enough to keep reading. _Shortcomings_ would have been way better if it had been about Miko. I thought at first it was going to be and then no. For what it’s worth my favorite story of his is “Hawiian Getaway” in Optic Nerve 6, which has a female protagonist, but if I went back and read it again, who knows, it might turn out to be more of the same–actually centering men as it pretends to be about women.

I haven’t read all of the stories in Killing and Dying, but I think Tomine has written good stories with female protagonists. In my opinion, one of his best is “Dylan and Donovan,” in which the narrator is a teenage girl who talks about her sullen outcast of a twin sister.

Many of the characterizations in “Amber Sweet” rang true to me, although admittedly most of them were about male characters. I believed Amber’s tactic of reacting to her fans with relentless, wholesome cheerfulness, presumably as a way of downplaying the fact that they’re basically strangers telling her that they’ve masturbated to her image. (And I think the story avoided cliches about porn star backgrounds by having Amber describe her own background as a cliche without elaborating.) Also, I liked how the story summed up the character of the narrator’s pseudo-screenwrter boyfriend in one panel, where he brags that he’s freaked out studio executives with his theory that all sequels are actually reboots. The two fratboy types who approach the narrator and her date were somewhat cliched, what with the backward baseball cap on one of them, but I think those types really do say things like, “Why you gotta be a bitch?”

None of this has much to do with whether he’s good at writing women, but anyway, I think he’s a very good writer.

If you showed those New Yorker covers to a sample size of women in a scientific survey, I find it hard to believe the result would be that the survey group finds them “creepy”. Even moreso if you don’t say whether the artist is male or female and asked for a “take” based on the art alone.

It’s not that the covers are creepy; it’s that staring is creepy. Those covers romanticize it.

Well my interpretation of the first cover is that two people notice they are reading the same book so decide they must be soul mates or something. Ironically they can’t talk to each other and may never meet again. It’s also framed in a way to possibly suggest the boy is the mirror image of the girl, like an artist’s self portrait, but maybe that’s a stretch. I wouldn’t assume this is something that happens to the girl every day, but a one time thing.

The second cover is a bunch of tourists doing tourist stuff but the teenage girl isn’t interested. Presumably she’s been dragged along by her family. It’s romanticizing being a reader who isn’t interested in staring, if anything. It reminds me of the opening of MTV’s Daria.

That’s my personal take on the covers, for that it’s worth.

Thinking about it further, if the first cover was a movie, we’d have a lot more context of who was looking at who and for how long and when. We may be making different assumptions about the chain of events that led to the moment in time in the first cover.

I thought Tomine’s intention in “Amber Sweet” (previously “My Porno Doppelganger” in Kramers Ergot) was definitely that the narrator was the porn star. Could having a porn lookalike really make her quit school and jobs, isn’t their meeting a coincidence, etc. So having the Amber Sweet she runs into declare herself to be the kind of person who “would” go into porn makes sense. It’s not a portrait of a real person. The attitude she gives her doppelganger about the harassment is not perfect, but would you expect it to be?

Jeez, that interpretation occurred to me at the end of the story, but I decided against it pretty quickly. I hadn’t noticed what Kim pointed out about the computer-search panel contradicting the narration, which does call the narration into question. Apart from the whole story being farfetched, which is true of a lot of fiction, are there any other suggestions that the narrator is Amber Sweet?

Hey Pallas, I think you’re missing my point. I read the covers in the same way you do. It’s not about the stories in themselves. IDK, I read on the train because I like to read. But I also read on the train so people won’t talk to me. The person staring at you on the train isn’t usually your soul mate. He’s usually a creep. So Tomine is taking an interaction that typically unfolds in a very different way and turning it into this special little romantic moment.

Conversely he depicts harassment as something that happens to a porn star in Killing and Dying. That is a sort of extreme and unusual context for something that occurs to all sorts of women all the time. Again, it’s not that I have a problem with that part of the story in itself. It just all adds up to my feeling that the way Tomine depicts women’s experiences is really misguided. The result of harassment is not usually that some bros punch your date and then men won’t date you, you know? Keep in mind that we are talking about a cartoonist who is heavily into realism.

Jack, whether or not these two characters are the same person is a subject I find interesting! Outside of the story, Tomine has made a lot of comments linking the story to Mulholland Drive, especially some stuff he said in an interview he did at Vulture. Inside the story, I’d point to parts of the broadness of the tone, little visual connections (Jane Doe in a pink bathroom, Amber Sweet with her pink website), the suggestion that Jane Doe’s parents are dead…

Either way I think the story is really bad, though.

I’d argue that ALL of the men in KILLING AND DYING are portrayed as harassers — certainly the guy who breaks into his old apartment is a harasser, and the father who berates his daughter and the drug dealer in Go Owls are all abusive pricks. I don’t think it’s “pathologically bad writing” to choose a certain topic – in this case damaged white men and the women they undermine, abuse and ignore – to concentrate on, which it’s done as well as Tomine does. What does alarm me, as I think it does you, when this is portrayed as the only possible subject for “serious” comics…which happens all the time.

Well, as Kim said, alternative comics are largely concerned with warts-and-all portrayals of neurotic, alienated white men. I guess that’s due partly to Crumb’s influence and partly to the fact that comics have always appealed to adolescent male misfits. It’s a subject that I find endlessly fascinating when it’s done well–which is why I’m glad Shortcomings was about Ben instead of Miko–but it’s obviously not for everyone.

I actually think comics have a pretty good track record when it comes to warts-and-all neurotic white guy stories when compared to other media. Have you ever seen Marc Maron’s t.v. show or just listened to him talking about his life at the beginning of his podcasts? There’s a neurotic antihero whose psychology and concerns seem totally banal to me; also, it seems like false self-deprecation in that he’s portraying himself as lovable on some level. I guess the warts-and-all neurotic antihero genre also includes the work of Lena Dunham and other women (I just watched the preview of Julie Klausner’s show Difficult People, which looks awful). Shortcomings and Chester Brown’s first two memoirs seem to shine a harsher light on their protagonists than most of this stuff, and even purely humorous comics work like Joe Matt’s has the virtue of being about a genuinely unusual person.

Hey Heidi, I’d argue that an abused or harassed woman still has the potential to be a fully imagined character. I don’t necessarily agree that all the male characters are abusive—that word feels too strong to me for the horticulture guy or the father, for instance (though I agree they can both be dicks). My point is that, although Tomine does explore a certain male type, he depicts those men in different ways as people with depth and dimension. His male characters have a wide variety of interests and they’re motivated by different things. They have a lot going on! The women aren’t imbued with all those shades of humanity. The main thing they have going on is some sort of ~man problem~.

I think Tomine’s limitations as a writer are most exposed in the stories with female protagonists, “Amber Sweet” and “Translated…”. It’s more than just the themes he’s exploring; it’s that he’s imagined a completely male-centric universe.

Kim, I think what you’ve pointed out is an ELEMENT of Tomine’s work, but I’m not sure how much of a FLAW it is. None of the characters besides the central male protagonists are given much inside life. They are character pieces. I thought “Killing and Dying” was one of of the best short comics I’ve read this year (or for several years) and a major leap for Tomine. Obviously, he’s writing what he knows: the insides of “neurotic, alienated white men.” Do I rank the work of “Golden Age” creators like the Hernandez Bros. who create nuanced portrayals of both sexes higher? Sure. And I think its fair to call Tomine out on his limitations. I just don’t think it’s fair to criticize him for something he wasn’t even attempting. The obvious mastery of his craft is what the critics you mention are responding to. Tomine’s work obviously calls for a deeper reading, but the title of this piece “Inflatable Dolls” is very unfair to the immensely sympathetic and unique females characters in this work.

Also, when indie cartoonists simply switch the genders of their protagonists you get some “interesting” work, like Paul Hornschemier’s Life With Mr Dangerous.

At any rate, I’m thrilled to see comics expand beyond the concerns of neurotic men who have problems with women, but if they are going to do them, doing them with the nuance, craft and empathy that Tomine used here is the way to go.

Okay, Heidi. Serious question: do you really think that Tomine was trying to write about the experience of neurotic alienated white men in Amber Sweet and Translations?

The idea that I’ve somehow dishonored his female characters with this essay…just…what? Or that I’m being unfair to Tomine or to right-minded critics like you who better comprehend his “obvious mastery”? I’m not saying he’s shit or that those critics are shit or that it’s bad and wrong to like Tomine’s work. I’m saying that in this book he’s very bad at writing women, and there’s an entire industry out there praising him for an honesty/humanity/perceptiveness that doesn’t really hold up when you look past his male characters.

It’s SO refreshing to hear someone critique Tomine on a meaningful level. Thank you for writing this. I hadn’t read any of his work for several years until I picked up “Summer Blonde” a few months ago for a reread and boy was I creeped out.

Thank you for writing this.

For all I know, Kim O’Connor is right about the comics, but pallas is right about the covers.

Also, three thoughts re the second cover, in the order that I had them:

1. Who still thinks kid read Catcher in the Rye?

2. No, wait, with an art style like that, he has to be a generation X-er at the very oldest (confirmed on Wikipedia: born 1974), and all gen X-ers know Catcher in the Rye is lame. It can’t be ignorance.

3. Oh, I get it, this is also the Wes Anderson aesthetic: Eternal nostalgia for a composite version of the early-to-mid-1960s (clothes by Carnaby Street, color scheme by Charles Schulz, soundtrack by the Kinks and the Velvet Underground). That book doesn’t just signify that she’s an Alienated Youth – for Tomine that’s a signifier of rare good taste.

Kim, thanks for articulating so well what upsets me about tomine’s work. i read a few optic nerves over the years back in the 90s, but when his recurring themes became obvious, repetitive and too easily parodied I stopped reading him. Interesting to see he’s still doing it. You nailed it in that one word: creepy. Even creepier to me is the way that people seem to love what he does.

I don’t understand the conflation of authorial intention and character/character perspective.

But (I meant to add!) – great critique.

“I also read on the train so people won’t talk to me. The person staring at you on the train isn’t usually your soul mate. He’s usually a creep.”

Hi Kim. I think what you’re sharing here is what makes me sad about humans nowadays. Reading to avoid social contact, to close ourselves in our own universe and believing that someone who looks for a social contact, for an exchange of looks is automatically a creep.

I may as well be a neurotic alienated male, I can’t but feeling alienated in a world where being a feminist means thinking in the rigid way you do. I think women around the world have bigger and more important battles to fight than the ones you are describing.

However I agree with you that the female characters in these stories do not pass the Bechdel test. That’s a shame.