By a photographic fiction I mean any work of fiction where at least part of the narrative is communicated to the audience via photography of some sort. The most obvious example of photographic fiction is live action cinema, although photocomics are another kind of photographic fiction that will be of great interest to typical PencilPanelPage readers.

By a photographic fiction I mean any work of fiction where at least part of the narrative is communicated to the audience via photography of some sort. The most obvious example of photographic fiction is live action cinema, although photocomics are another kind of photographic fiction that will be of great interest to typical PencilPanelPage readers.

Now, one natural thought we might have about photographic fictions, as opposed to non-photographic fictions, is that the characters in these stories appear exactly as they are depicted in the photographs that partially or completely make up the fiction. As a result, we might be tempted to accept the following two claims:

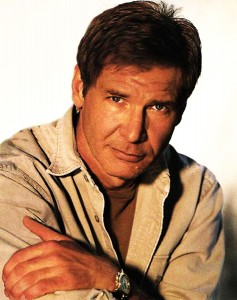

- In A New Hope, Han Solo’s fictional appearance (e.g. what he looks like when other characters see him, and how we are to imagine him appearing when we are experiencing the fiction) is the same as Harrison Ford’s actual appearance.

- In Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones’ fictional appearance (e.g. what he looks like when other characters see him, and how we are to imagine him appearing when we are experiencing the fiction) is the same as Harrison Ford’s actual appearance.

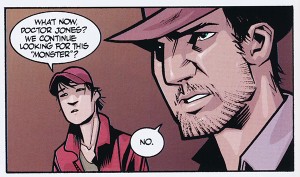

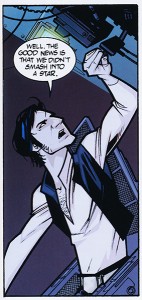

But now consider the ten-page comic titled “Into the Great Unknown”. “Into the Great Unknown” appears in issue #19 of the anthology comic Star Wars Tales. In this story Han Solo and Chewbacca crash the Millenium Falcon in a forest on an unknown planet after a blind hyperspace jump. The Falcon is irreparable, and Han is eventually killed by the locals (who turn out to be late 18th century inhabitants of the Portland area). More than a century later the wreckage of the Falcon is discovered by – wait for it – Indiana Jones, with Chewbacca, who is now also Sasquatch, observing from afar.

But now consider the ten-page comic titled “Into the Great Unknown”. “Into the Great Unknown” appears in issue #19 of the anthology comic Star Wars Tales. In this story Han Solo and Chewbacca crash the Millenium Falcon in a forest on an unknown planet after a blind hyperspace jump. The Falcon is irreparable, and Han is eventually killed by the locals (who turn out to be late 18th century inhabitants of the Portland area). More than a century later the wreckage of the Falcon is discovered by – wait for it – Indiana Jones, with Chewbacca, who is now also Sasquatch, observing from afar.

Now, even though the stories in Star Wars Tales are explicitly non-canonical (in virtue of a framing story we need not get into), it still seems that the following are plausible constraints on a proper interpretation of this story:

- Everything fictionally true of Han Solo in the canonical Star Wars fiction is also true of Han Solo in the imaginary/non-canonical story “Into the Great Unknown”.

- Everything fictionally true of Indiana Jones in the canonical Raiders of the Lost Ark fiction is also true of Indiana Jones in the imaginary/non-canonical story “Into the Great Unknown”.

Note that we don’t, of course, want to accept the converses of these statements – that’s the upshot of the story being non-canonical.

But if all of this is right, then it would seem to follow that, when interpreting “Into the Great Unknown”, we should accept the following:

- In “Into the Great Unknown”, Han Solo’s fictional appearance is the same as Harrison Ford’s actual appearance.

- In “Into the Great Unknown”, Indian Jones’ fictional appearance is the same as Harrison Ford’s actual appearance.

But these, in turn, imply:

- In “Into the Great Unknown”, Han Solo and Indiana Jones are identical in appearance.

And surely this is not something we are meant to imagine to be true in the story. Of course, the story is in some sense meant to make us metafictionally ponder the role that appearance and actor identity plays in the nature of fiction. But it would be a mistake to assume, within the fictional world portrayed by this ten page comic, that Chewbacca is immensely confused when Indiana Jones appears on the scene, since Indy looks exactly like his old, now dead friend Han Solo. Wouldn’t it?

Actually, things are even a bit more complicated than this. The above discussion assumed that the photographs that provide much of the content of A New Hope (or Raiders of the Lost Ark) provide us with accurate, objective, reliable information regarding Han Solo’s appearance (or Indiana Jones’ appearance) in virtue of providing us with accurate, objective, reliable information about Harrison Ford’s appearance. But this is too simple. Even if we accept the controversial claim that, when viewing a photograph, we genuinely see the objects depicted in the photograph, this does not mean that we see such objects as they truly are in the world. This point is nicely emphasized by Susan Sontag in her influential On Photography:

Actually, things are even a bit more complicated than this. The above discussion assumed that the photographs that provide much of the content of A New Hope (or Raiders of the Lost Ark) provide us with accurate, objective, reliable information regarding Han Solo’s appearance (or Indiana Jones’ appearance) in virtue of providing us with accurate, objective, reliable information about Harrison Ford’s appearance. But this is too simple. Even if we accept the controversial claim that, when viewing a photograph, we genuinely see the objects depicted in the photograph, this does not mean that we see such objects as they truly are in the world. This point is nicely emphasized by Susan Sontag in her influential On Photography:

But despite the presumption of veracity that gives all photographs authority, interest, seductiveness, the work that photographers do is no generic exception to the usually shady commerce between art and truth. Even when photographers are most concerned with mirroring reality, they are still haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscience… In deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects. Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as paintings or drawings are. (1971: 6-7)

In other words, when we look at a photograph of Harrison Ford, we don’t see Harrison Ford as he actually appeared when photographed, but instead see Harrison Ford as mediated through the stylistic, technical, and aesthetics choices of the photographer.

Nevertheless, it does seem like we are meant to take the photographs that appear in photographic fictions to be unmediated and (all else being equal) accurate depictions of the fictional characters being depicted. Thus, when viewing Star Wars, we are being shown Harrison Ford’s appearance as mediated by the aesthetic/technical/stylistic choices of Gilbert Taylor (A New Hope‘s cinematographer) and others, but we are being shown Han Solo as he really appears within the fiction. In other words, the various interpretational choices made by Taylor and others interfere with our direct access to what Harrison Ford looked like at the exact moment he was photographed, but those same choices are partially constitutive of what Han Solo looks like during the fictional events depicted by those same photographs. In short, the information these photographs provide regarding the appearance of the fictional characters depicted in the films is more reliable than the information the same photographs provide regarding the appearance of the actors who play those characters.

But this makes the situation even more puzzling than before. First off, it seems like we still ought to accept:

- In “Into the Great Unknown”, Han Solo and Indiana Jones are identical (or nearly identical) in appearance.

since the photographs that provide us with canonical information regarding the appearance of both of these characters do depict these characters as having identical, or nearly identical, appearances. But we need not accept that:

- In “Into the Great Unknown”, Han Solo looks exactly like Harrison Ford.

- In “Into the Great Unknown”, Indiana Jones looks exactly like Harrison Ford.

We’ve already seen the reason: Our information regarding the fictional appearance of Harrison Ford is always mediated via the choices made by the photographer. In short, Han Solo looks just like Indiana Jones, but this is compatible with it turning out that neither of them looks very much like Harrison Ford (although they will both look very much like the relevant photographs of Harrison Ford). And this is just plain weird.

I think the problem with the likenesses is mediated by the comic book format. The art is stylized and too general to require that characters acknowledge the resemblance, or for the reader to infer that its versions of Jones and Solo look exactly like a photographic record of Harrison Ford in some implied, fleshed-out version; thus, the comic and the movies both exist in relation to each other as interpretations only, of a never-manifested ur-narrative. A live-action version or a photo-realist drawing style would be more pressured to acknowledge the resemblance.

OK, I just read the comic digitally and it looks like it is premised on the characters being identical, with implied reincarnation. Jones comments that the ruins of the Millennium Falcon “seem familiar”. His face is in shadow and his identity is withheld until the panel Cook clips here, which is also the point at which he decides to stop hunting for the Sasquatch/Chewbacca, where before he was determined to capture him. Chewbacca’s reaction is not revealed at all; he’s only shown watching from the back. Why wouldn’t he pursue him? Presumably it’s the same choice that Jones makes when he decides to “leave it to the great unknown,” and as a non-human, non-speaking character he’s allowed to have a transcendent perspective.

1) Roy, this:

“In other words, when we look at a photograph of Harrison Ford, we don’t see Harrison Ford as he actually appeared when photographed, but instead see Harrison Ford as mediated through the stylistic, technical, and aesthetics choices of the photographer.”

seems to need a lot more argumentative support than you give it here. I know you can’t argue for every thing in a blog post. (Explanations have to end somewhere, after all.) But I don’t see a straight implication from “this photo is mediated” to “this photo doesn’t show you the object as it actually appeared”.

2) Also, I’m not clear on how this “puzzle” is different from more general puzzles about fiction. I’m thinking of distinctions between what we take to be genuine representations of diegetic elements, and mere stylistic flourishes — an issue that arises especially vividly in corporate comics produced by more than one team over time.

e.g. Compare Manhattan skyscrapers as drawn by Kirby and Buscema — presumably it’s not true that they looked like *this* at first, and then like *that*. (Kirby’s skyscrapers look nothing like real skyscrapers). By contrast, their Thors are supposed to look the same — blond hair, red cape, yellow boots, etc.

Egon,

I hadn’t considered the reincarnation interpretation (I thought the “seems familiar” comment was more a metafictional nod in the direction of the audience, hinting at the metafictional issues). Interesting, but I am not sure I am convinced.

Jones,

I completely agree about the insufficiency of the argument I presented from mediated to appearing differently from how it would appear in person. But I think it’s a not unreasonable thought to have about how photography often works, and might be working in this case (after all, the sort of photography at work in Hollywood movie-making is usually REALLY mediated by all sorts of effects and processed that occur between the light hitting the film (in the camera) and the film (the artwork) hitting the screen at the theater.

Second, I agree with you that this is just a variant of the sorts of puzzles about the appearance of things in visual fictions more generally (which include, but are certainly not limited to, pinning down what, exactly, if anything, underwrites the diegetic versus stylistic elements of images. I’ve written a good bit about this, both here and in published academic work.

But I do think something additional is going on here, beyond just the diegesis/style issue. Because here we have more than a puzzle regarding which bits of the images we are to take to be diegetic and which merely stylistic. In addition, we have something very near to an outright contradiction (if we set aside the reincarnation interpretation): we have two distinct characters where we are presumably meant to imagine that each of them closely resembles the real-life person who portrayed them in other media (or at least both closely resemble the relevant photographic images of that person), but where it would be bizarre to imagine them as closely resembling each other in the story in question.

“I’ve written a good bit about this, both here and in published academic work.”

Is any of the academic stuff online?

Isn’t there a long tradition of having characters who implausibly resemble each other in fiction? Tale of Two Cities hinges on that, right? And soap operas… Soap operas go the opposite way too, where you have one character who suddenly looks completely different (another actor playing them) and no one notices.

Jones,

Here is an incomplete bibliography of my work that touches on the issue of pictorial representation in comics, and how we should understand the relation between how the drawings in a comic look and what we should understand them to represent as being true within the fiction (the topic pops up in other papers of mine, but these are the main ones on the topic):

“Judging a Comic Book by its Cover: Marvel Comics, Photocovers, and the Objectivity of Photography”, Image and Narrative 16(2), 2015: 14 – 27.

“Morrison, Magic, and Visualizing the Word: Text as Image in Vimanarama”, ImageText 8(2), 2015: online at http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v8.2/cook/

“Does the Joker Have Six-inch Teeth?”, in The Joker: A Serious Study of the Clown Prince of Crime, R. Weiner & R. Peaslee (eds.), University Press of Mississippi 2015: 19 – 32.

“Drawings of Photographs in Comics”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 70, 2012: 129 – 138.

Noah:

I actually think that, with regard to how fictional truth works (i.e. what we are meant to understand to be true in the world of the fiction when experiencing said fiction), daytime soap operas are a treasure-trove of undiscovered puzzles. The one about actors switching without anyone noticing in the story noticing the difference is a really cool one.

Didn’t the TV show Roseanne play with this, with two actresses sharing the role of Becky in one of the seasons, and subtle references to Roseanne liking one version better than the other (or something like this – I was never a huge fan of the show, and only vaguely remember something like this).

I’ve never seen Roseanne! That sounds cool though.

Now that I’ve seen The Force Awakens, this post, and the issue of determining what’s true of Han Solo and Indiana Jones in “Into the Great Unknown”, has all sorts of new facets. Interestingly, pre-August 2014 (the date of the “great uncanonizing of the EU”) this short non-canonical story was incompatible with Chewbacca’s in-canon death. Between August 2014 and now it was consistent with canon, but now isn’t (due to another death). Interesting.