At its core, Hollywood is an engine for turning pain, hardship, and trauma into shallow inspiration porn. From paralysis to the Holocaust, slavery to cancer; Hollywood cheerfully takes these blood soaked lemons and makes you drink blood soaked lemonade, albeit with lots of sweetener.

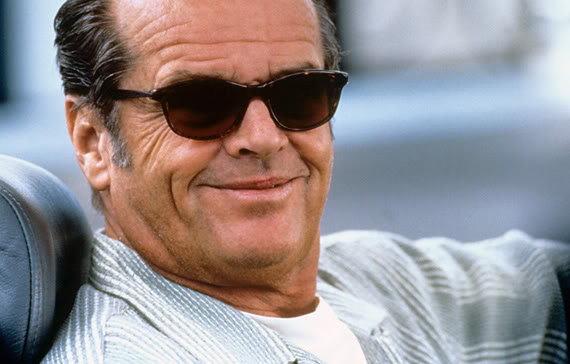

As Good As It Gets is firmly in the tradition, though the cocktail in question is perhaps more repulsive than most. Part of that is thanks to Jack Nicholson, whose smug self-regard can barely be contained in his constantly arching eyebrows. Most of the blame, though, rests squarely on the script.

For those lucky enough to have avoided the film since its release in 1997, I’ll briefly recap what I suppose I’ll have to refer to as the plot. Nicholson plays Melvin Udall, a fabulously wealthy romance novelist who suffers from some undefined form of OCD; he won’t step on cracks in the sidewalk, he locks the door five times every time he walks into his apartment; he opens a new bar of soap every time he washes his hands; he’s germphobic. Oh, and he’s also homophobic, racist, and deliberately abusive and cruel to everyone. But then he gets a dog, and a woman who looks like Helen Hunt and is 20 years younger than him decides inexplicably that he’s the guy for her. He gives her money to help her asthmatic son, life lessons and becomes a better person. The end.

There’s basically nothing to like in this film, but the bit that sticks out as particularly, drearily awful is the treatment of Melvin’s disability. At the Dissolve a while back, a commenter with OCD named Chapman Baxter argued that the film was correct in that people with OCD can engage in assholish behavior; “Although I’m not proud to admit it, I know from experience how a constant compulsion to do methodical rituals and the perpetual anxiety of intrusive thoughts can make one behave in quite an irritable and anti-social manner.” That seems reasonable…but I think it misses the main problem with what the film is doing.

The movie doesn’t just suggest that Melvin is a jerk because he has OCD. It suggests that the OCD and the jerkishness are essentially one and the same. When Melvin calls his gay neighbor a “fag”, it’s a sign of his quirky woundedness, just like his nervousness about stepping on cracks. And, similarly, when Melvin needs to eat at the same table in the same diner every day, that’s a character flaw on par with insulting a Jewish couple for having big noses. Melvin’s cruelty and his illness merge together, he’s at one and the same time responsible for both and for neither.

Because Melvin’s awfulness is an illness, he gets a pass; he can be spectacularly horrible, but still basically a good person underneath it all, since his behavior is essentially a medical condition, outside of his control. And because his illness is a character flaw, it is curable via the all-purpose nostrum of true love. Mixing flaws and sickness allows Hollywood to blend two of its favorite genres—the rom com and disability inspiration porn. The love of Carol, the waitress played by Hunt, makes Melvin want to become a better, less bigoted man—and that love simultaneously and spontaneously causes him to overcome his germphobia and other manifestations of his OCD. Mental illness and racism both evaporate with a kiss. Fall in love, and you can step on a crack.

This is supposed to be a happy ending for both Carol and Melvin, in theory. In fact, it’s impossible to imagine that this is a good long term choice for Carol, who, understandably, protests against her narrative fate, tearfully demanding to know why she has to settle for this decades older bigot who has just barely learned to form casual friendships, much less a serious romantic partnership. Carol’s mother is wheeled out on cue to tell her that nobody ever gets a perfect boyfriend—the uplifting message of the film being, you might as well settle, girl. We know you’re desperate.

Nor is this in any sense a happy ending for Melvin. Yes, Carol unaccountably decides to date him. But her love is precisely predicated on him becoming a better man–not just by being less of an asshole, but by being less mentally ill. There’s no sense that Carol is willing, able, or interested in dealing with Melvin’s illness; instead her love, the film assures us, will make that illness go away. What if it doesn’t, though? What happens to their relationship then?

As Good As It Gets, in short, is blandly contemptuous of both of its protagonists. Carol, with her asthmatic son, mentally ill boyfriend, and heart of gold, is a human mop, admirable by virtue of the selfless sopping up of her loved ones messes. When she suggests she might deserve more, her mother (presented as a moral voice of truth) tells her to quit kidding herself. Melvin, for his part, is presented as only worthy of love to the extent that love is a miraculous cure. Women are nurses who exist to make men normal. And if the woman doesn’t want to be a nurse, or the man isn’t instantly cured? Sorry, no rom com for you.

The forced happy ending is supposed to be inspiring; an unlikely boon to two wounded people. But instead it feels like an act of cynical, manipulative loathing. A working-class waitress with a sick kid; an aging man with OCD—without Hollywood pixie dust, no one gives a shit about you, the movie taunts. Follow the script for your gender and your illness, and all the normal people will maybe deign to sympathize. Romance! Cure! Come on kids; this is as good as it gets.

The thing I couldn’t get past with this movie was its use of the song, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life”. It’s been long enough since I’ve seen it that I don’t remember just _how_ the movie used the song, but I do remember that it seemed unaware of the song’s meaning and original context. (And that’s a very specific and potent original context. I would think that you wouldn’t want to invoke it casually.) I had the same reaction when Eric Idle sang it during the London Olympics closing ceremonies. I was all, “the people who organized this… do they know what this song implies? Do they care? Do they _want_ these associations?” I mean, I can’t imagine that they did, but how could they not? Baffling.

I saw this movie back in ’98 or so, but I don’t remember liking it that much. Except for Greg Kinnear’s gay neighbor–and his dog. What you said about settling is true, especially since it would solve a lot of her money problems. But although there’s truth to the “being a better man” part of the essay (love can cure his illness, etc.), I thought being a better man for her meant he wanted to take his pills. The medication and going to a therapist eased his OCD, not just love.

It was really unclear what was happening with the pills. Was he even taking them regularly? I don’t think there even *is* medicine for a lot of OCD; it’s quite difficult to treat, is my admittedly not super well informed understanding. But I think the idea that he could just take a pill and make it go away…it’s Hollywood pixie dust.

I guess I would have read it: “That little voice inside my head telling me ‘You, aging Hollywood screenwriter/director/star, are pathetic for seriously wanting to be with women half your age, and an asshole for your inability to control your id’ is wrong – I’m actually a great catch!'” But I suppose it could be more as you say – or both.

“…do they know what this song implies? Do they care? Do they _want_ these associations?”

Pretty sure everyone in Britain knows what the song is about (well, maybe not the very young ones). It’s a song for the losers (who form the majority of Olympians) – you lost, you wasted your time, and now all you’ve got to look forward to is death. It’s called British humour.

@Matthew E I would argue that if a song’s meaning doesn’t come across outside of its original context, then maybe the meaning was always pretty superficial.

@Ng Suat Tong Britain (England, rather) – the only country that found a way to be pedantic about being funny.

Graham, I think it’s both.

I’m curious to see if anyone is a fan of this film. It won multiple academy awards less than 10 years ago, so I presume there must be enthusiasts out there, but I haven’t encountered any of them.

Noah, I saw it once in the nineties, and while I remember wincing at much of Nicholson’s behavior, I didn’t hate it. I don’t remember it well enough to defend it, however. Also, there is medication to reduce the anxiety that causes the compulsive behavior. Another likely effect of reduced anxiety would be enabling Nicholson to be a bit more empathetic.

Would a fairer way to summarize the Mom speech be, “Don’t undervalue or discount what you’ve got just because it doesn’t match what you were looking for”? I recognize that fairness may not be the objective here.

I seem to remember that for some reason somebody thought it would be a good idea to screen it in class, when I was in either middle or high school (1996-2003). The Age of Caring About the Oscars was weird. (1994-2002)

Graham, the song is crystal clear, regardless of context. Unless you change the lyrics.

your review seems to confirm any prejudice i subconsciously had against this film, which i never considered to see in the first place. what did you expect? was there ever anything good like this? im actually sure there must be …

PS nice Hollywood bashing

John, I don’t know if that would be a fairer way. Carol says, why do I have to have a boyfriend who is a mess, and her mom says, well, life’s tough. I disagree with her mom; she should under no circumstances date that idiot, and she does in fact deserve better.

The film I think deliberately draws into question whether Melvin is taking his pills regularly. He may or may not be. They want to leave the possibility open that love cured him.

Understood, Noah. I’m probably giving it too much credit, since I don’t remember it well.

NOAH: “Carol says, why do I have to have a boyfriend who is a mess, and her mom says, well, life’s tough. I disagree with her mom; she should under no circumstances date that idiot, and she does in fact deserve better.”

Sure, she could likely find a more suitable partner. But that’s not the point. This is a moral lesson, addressed at the viewer, about accepting that your life, right here, is “as good as it gets”.

This fits with my own atheist world view. Religion promises something better in the afterlife. As an echo of that, society as a whole believe in this constant strive for something “new”, constant “change”. This is an illusion. I have been on this planet long enough to have a pretty good idea of what it has to offer, there is nothing shiny around the corner. This, right here, is my life, and this nasty old fart, this piece of shit, is me. And it’s permadeath, no reload. Yeah, it is horrible. But that’s all you get. Suck it up.

Me, I think the film succeded at delivering a hard message, while at the same time keeping itself in feel-good teritory.

“there is no afterlife” is a significantly different message from, “you can’t get a boyfriend who treats you right and who is not a racist asshole.”

“I think the film succeded at delivering a hard message, while at the same time keeping itself in feel-good teritory.”

The second half of your statement is not reconcilable with the first half, imo.

Noah: “there is no afterlife” is a significantly different message from, “you can’t get a boyfriend who treats you right and who is not a racist asshole.”

I think we’re viewing this scene from completely different vantage points. You are looking at the advice the woman is recieving. Which is crap advice, granted. But I’m looking at what message the filmmaker/mother is trying to tell the viewer.

When film makers do this message thing, one shouldn’t make a literal interpretation. Like, PRINCESS is a movie about a priest who commits terrorism with a toddler as a sidekick. But its message is criticism of the porn industry.

‘This is as good as it gets’ is a hard message, I think. But the film is undeniably feel-good. You say these two can’t mix. But I don’t know what to do about that. I just tell how I remember the film.

Likewise, I think the ending of LIFE OF BRIAN succeded at reminding me of my own mortality, while at the same time keeping itself in low-brow comedy territory.

“But I’m looking at what message the filmmaker/mother is trying to tell the viewer.”

I’ll agree that the intent of the film was probably not to tell women they should date racists. Sometimes films don’t quite do what their filmmakers intended, perhaps because the filmmakers screwed up, or because they’re kind of dumb, or for other reasons.

I don’t think As Good As It Gets has a hard message, because it is feel good tripe. “You can control your OCD if you just fall in love” is not in fact a hard message. It is a stupid message.

Life of Brian is a much, much better movie, and low-brow comedy and discussions of mortality are in no way at odds with one another (ask Beckett.)

Maybe one take away here is that reminding you or your mortality is not actually a hard message at all. (Reminding you of what the last five years of your mortality are likely to be, now that…)