The differences between the worlds of comics and fine art would appear to be pretty obvious, but my recent reading of Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World suggests that these differences might be less than they would appear, the great leveler in this instance being human nature.

Taking in subjects like a high end contemporary art auction, self-absorbed art students at a “Crit” session, the strange world of Artforum magazine and a trip to Takashi Murakami’s studio, the entire experience of perusing Thornton’s book was not unlike reading about the decline of civilization (Western in this case but the values are universal); a kind of journal describing that surge of decadence which sometimes marks the end of empire.

I’ll leave that journey of discovery to the would be reader of Thornton’s book and will instead offer three short excerpts from Seven Days in the Art World which suggests that when it comes to money and collecting, there are in fact many similarities between comics and the rarefied realms of fine art.

(1)

How does Segalot know when he has encountered the right work? “You feel something,” he says with fervor. “I never read about art. I’m not interested in the literature about art. I get all the art magazines, but I don’t read them. I don’t want to be influenced by the reviews. I look. I fill myself with images. It is not necessary to speak so much about art. I am convinced that a great work speaks for itself.” A faith in gut instinct is common to most collectors, consultants, and dealers, and they love to talk about it. However, it is rare to find an art professional willing to admit that he doesn’t read about art. It takes bravado. The vast majority of subscribers to art magazines do simply look at the pictures, and many collectors complain that art criticism, particularly that found in the dominant trade magazine, Artforum, is unreadable. Most consultants, however, pride themselves on their thorough research.

Phillippe Segalot, art consultant, formerly of Christie’s and now with an art consultancy called Giraud, Pissaro, Segalot

We all know about cartoonists who don’t read reviews or comics criticism, but did you know that many collectors of comics art don’t even bother keeping up with the comic books arriving on the stands every month? They really don’t need to since they are largely interested in what they read a few decades ago. As far as comic art is concerned, that gut refers not only to the gut of personal taste but also to the liver of investment potential and the bladder of nostalgia. One hardly needs to develop one’s taste when the superhero form (the genre of choice in the American comics art market) remains largely static in its values and aesthetics

As for the world of contemporary art, you may have also have heard of collectors who are only interested in the artist’s name and not the specific piece they are buying. Thornton pursues another more traditional angle in her book and highlights a number of prominent collectors who are in fact dedicated collectors of “young” art; a breed of collector who finds that extra thrill in finding pieces unsullied by the stain of popularity:

On another occasion Mera [Rubell] told me, “How do you know when you need to acquire a piece? How do you know when you are in love? If you listen to your emotions, you just know.” On a more rational note, Don added, “We meet the vast majority of artists, because when you’re acquiring young work, you can’t judge it by the art alone. You have to judge it by the character of the person making it.” And Mera elaborated: “Occasionally meeting an artist destroys the art. You almost don’t trust it. You think what you’re seeing in the work is an accident.” Then Don wrapped it up: “What we’re looking for is integrity.”

(2)

Cappelazzo is refreshingly unpretentious. When I asked her, What kind of art does well at auction? Her answer was uncannily appropriate to this lot. First, “people have a litmus test with color. Brown paintings don’t self as well as blue or red paintings. A glum painting is not going to go as well as a painting that makes people feel happy.” Second, certain subject matters are more commercial than others: “A male nude doesn’t usually go over as well as a buxom female.” Third, painting tends to fare better than other media. “Collectors get confused and concerned about things that plug in. They shy away from art that looks complicated to install.” Finally, size makes a difference. “Anything larger than the standard dimension of a Park Avenue elevator generally cuts out a certain sector of the market.” Cappelazzo is keen to make clear that “these are just basic commercial benchmarks that have nothing to do with artistic merit.

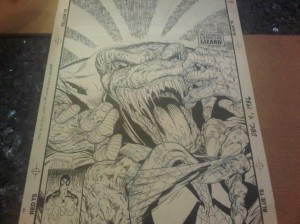

[From the collection of Patrick Sun]

Cost of an Adam Hughes sketch of Zatanna, Dejah Thorris, Power Girl etc. with breasts spilling out of clothes? Probably a few thousand bucks. Cost of an Adam Hughes sketch of Batman…? Only an idiot asks Adam Hughes to draw Batman. Still, sometimes, just sometimes, the comics art world does go out on a limb. This Amazing Spider-Man cover by Todd McFarlane recently sold for $71,200 on eBay:

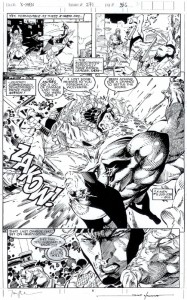

[From the collection of B B]

A deep (pocketed mainly) and dedicated collector’s pool has been cited as the main reason for the final price.

(3)

Few like to admit that they enjoy selling art. The experience certainly contrasts markedly with the glory of buying. For collectors, the traditional reasons for selling are the “three D’s”death, debt, and divorce so the act has been associated with misfortune and social embarrassment. Today, says Josh Baer, there are “four D’s — because you’ve got to take account of the collectors who are effectively dealing.” Many collectors are in the practice of rotating their collection, much as dealers rotate their stock. They sell overvalued objects whose prices have moved up at rates that are historically unsustainable and buy undervalued works that they think are more likely to stand the test of time. Or they sell off objects by less fashionable artists before the works are worth nothing at ail, in order to “upgrade” their collection. As one Sotheby’s specialist explained, “Many collectors who consign works to auction are of-the-moment people who have a very plastic approach to their collection.

With such an attitude in evidence, it will come as little surprise that the individuals who have acquired the works of Damien Hirst are sometimes referred to as his “investors”.

A number of famous galleries (and I am talking about the primary art market here) make a big show of disapproving of speculation. They want the right kind of collector for their pieces, the kind that will buy, hold and add prestige and value to an artist’s work. This is not, I suspect, because of any profound philosophical differences when it comes to the subjects of art and commerce but because of the harm this practice can wreak on the market not only through its dilutional effect (false scarcity being just another marketing tool) but also in the “unlikely” event that the art sells for less than the gallery’s asking price.

This kind of “amateur” dealing is frowned upon even in the small stakes game that is the comics original art market. The strength of comics fan culture is such that the idea of flipping a recently acquired piece (or even “grail”; a term tossed around increasingly carelessly nowadays) is considered not the best practice. Yet the collector turned amateur dealer is now so common that it barely raises any eyebrows except, perhaps, among older collectors used to “kinder”, “gentler” days; that obsessive acquisitiveness being a kind of “University of Dealing” which, when turned to commercial ends, justifies the hours said collector has spent combing eBay, their contact list and the rest of the internet. A number of dealers were (and are) collectors first and such is the price of original art (cheap in comparison to other collectibles) that they often keep the very best pieces for themselves, something not usually possible in the high end contemporary art market.

At the most basic level, there are many collectors who believe in acquiring a significant stock of “blue chip” original art for purposes of trading. This is sometimes seen as the only means by which one is able to acquire the pieces one desires from fellow collectors. The collector who refrains from doing so is often considered imprudent or naive. It is, however, always wise to ensure that one doesn’t make a fool of oneself while engaging in such activities as some fickle collectors are wont to do. I’ll close with that thought and this little snippet I picked up on my travels through the galleries at Comic Art Fans…an ode to the joys of collecting and the acquisition of a “grail”:

“Uncanny X-Men #271 is my favorite issue artwise from Jim Lee and Scott Williams’ run on the X-Men. There is something about the layouts, the figure work, the rendering, the inking… just everything about the book that clicks with me. I would like to collect the entire book’s originals, but the task is too daunting. One drawback is that while I love the interior art, I never liked the design of the cover. SOLD. Thank you!”

Very sharp post, Suat. I’ve read the book, and I heartily second your recommendation.

I’ve worked in art galleries, and I’ve been a comics fan for 40 years– occasionally trading. To some readers, it may seem that your parallels between the ‘fine art’ and comics art businesses area bit of puckish satire. No. The parallels are exact.

Some of the crap I’ve seen…when I worked for the gallery Artcurial, which is L’Oreal’s Paris-based gallery and fine-arts subsidiary, I saw something that in retrospect filled me with shame.

The gallery had invested heavily in contemporary editions of prints, clothes, and ceramics designed by Sonia Delauney. Came the vernissage, with a glittering guest list.

As it happened, Delauney was dying of emphysema and couldn’t possibly be present.

No problem– they chartered an ambulance and bullied the poor old woman into coming. She was wheeled into the building on a stretcher, forced onto a wheelchair (which was beyond her strength) and paraded for the benefit of the Beautiful People for 10 minutes.

I saw her on her way back home: she was unconscious.

(I speak of my shame: it comes from my not burning down the damn place after this.)

What an horrible thing to happen to one of the greatest painters of the 20th century. That’s disrespect, pure and simple.

Here’s more about the att mahket: http://tinyurl.com/35omuc5

“the bladder of nostalgia.” That’s a keeper.

that this should come as a surprise to anyone who has followed what is, essentially, a market borne of the same individuals is bizarre. Original pieces, the nostalgia, the specialization in either a type of art or a subject matter, all are the same. Its just that the art market for comics is so small potatoes it hasn’t come under the same scrutiny as the “real” art market.Recent $$ amounts on ebay and at heritage have made the rest of the world sit and take notice a little bit more.

My impression of the fine art market is that academic art is very complicit with it, that there’s a lot of cross-pollination with gallery culture in contemporary art studies. I’m sure art criticism is also less of a powerhouse now than in the 50s-60s, but it looks from the outside like it still exerts more market influence percentage-wise than literary criticism. Is that wrong?

If it’s right, it seems like it’s not true for comics; or am I just missing a connection between criticism and the comics market?

I bring this up because gallery culture is notoriously elitist and art academics is also not particularly populist: I’m thinking of that article about Jeff Wall and conceptual art and the artists’ desire to claim some control over their status and the interpretation of their work, and it seems like the political situation is kind of inverted in fine art from comics and literature.

Of course, art is also more cliquish and subcultural at the undergrad level than literature (although literature catches up at the grad level) so that’s probably also something art and comics have in common.

I feel like I should make a chart.

In literature we went through this period when academics naval gazed at the politics of the english department — we still do that from time to time but the rise of theory prompted a barrage of monographs on it. The ones I remember from being a newbie grad student are “Is Literary History Possible” and “Professing Literature,” but there were dozens of them, all these intense critiques of insitutional practice and pedagogical practice and the canon and the idea of “expertise” in literature. Pedagogy basically got turned upside down and the departments became really anti-elitist at the undergrad level (to the point that I had grad colleagues who didn’t know what a participle was) and really intensely professionalized at the grad level, i.e., theoretical to the point of obscurantism while deeply populist and political at the level of discourse.

Did academic art go through a similar period of self-analysis and political reorientation post-counterculture? And did it influence the relationship or involvement of academia in the market?

There’s nothing comparable to the art market for books: “originals” are either monographs held by artists’ papers in libraries, which is academia proper, or they’re first editions, which academia has no interest in.

Charles: I think there is at least one significant difference between the fine art market and comics original art. Comics OA cleaves closer to collectibles like CGC comics and baseball cards (?) as far as its attractions to the general collector are concerned. The nostalgia factor is immense.

Caro: Art criticism having more leverage/influence than literary criticism? The other book I read on the subject (The 12M Dollar Stuffed Shark, written by an economist) suggests that art criticism has very little influence (try as the critics might) on what makes it to the “top” of the money game. Thornton’s book has a completely different take and actually discusses two well known art critics (Jerry Salz and Roberta Smith if memory serves) and their influence on gallery sales (or at least their relationship with galleries and their shows). Maybe someone like Robert Boyd knows more about this or even Alex since he’s worked in galleries (interesting story about Delaunay btw, though I may still have to buy things through Artcurial in the future).

Comics original art is connected directly to the comics they first appeared in, and comics criticism seems to have very little bearing for the most part. Remember, we’re talking about superhero comics in the main, so the force of opinion seems to lie with fandom and the masses (us). I think criticism may have a role in consolidating opinion but there’s very little objectivity in assessments especially for art from the last few decades. The nostalgia factor is something which a lot of the major collectors/traders accept, relish and prey on.

Literary critics may have a very small role in the book market (first editions, manuscripts, notes, letters etc.), especially when they take part in populist things like the Modern Library 100 Best Novels. Pushes those books into the public eye, elevates their status, increases the sale of leather bound collector’s editions and the prestige of owning a first editions/manuscript. Pretty insignificant compared to the contemporary art market though.

Suat: don’t hesitate, Artcurial boasts of having the most extensive art bookshop in the world. They just may be right.

Caro: I don’t think art critics have the same effect as in, say, the ’50s, when a Clement Greenberg could make or undo an entire career.

Actually, this is true of criticism/reviewing in general. Perhaps the sole exception is the theater. One bad review from the New York Times can close a show overnight.

Hmm…restaurant reviews are also mighty, come to think of it…

A quick thought about collecting original comic art and nostalgia:

Collectors fetishize “fresh to market” pieces. They complain when pieces are “shopped around.” They’ll admit to not liking to think about who owned the piece before them. While the sexual undercurrents are barely even undercurrents, I think this comes down to the nostalgic impulse, and the comic art collector’s fraught relationship with mass culture.

Basically, the comic collector has this ongoing geek/fan cognitive dissonance about his (less often her) devotions. S/he loves a comic and takes heart in knowing that others love it too, that s/he’s part of a mass audience, and all that jazz. But his or her love of that comic is also part of his or her self image… “my love of band x, comic y, and movie z make me who I am.” It’s a devotion that is simultaneously public and personal.

Buying the original art can seem like a way to solve the problem. The buyer is still part of the fan community, but they also gain access to the original in all of its auratic glory (apologies to Benjamin).

But the glow is diminished when they know that other fans have had the same piece, and didn’t even value it enough to keep it. Anyway, I’ll stop now before this brain fart comes full circle back to the sex thing.

And by the way, the above is not true of all (or even most comic art collectors I know and have known… just a few).

The “fresh to market” thing is certainly much discussed in OA circles. The sexual connotations less so but undoubtedly apt in this instance. I think the effect is far greater than you suggest. Art reserved as trade fodder is usually not put up on CAF because of this.

“I’m sure art criticism is also less of a powerhouse now than in the 50s-60s, but it looks from the outside like it still exerts more market influence percentage-wise than literary criticism. Is that wrong?”

Comparing it to literary criticism is not useful because of the difference in markets for literature as opposed to original art. A painting by, say, Peter Doig can sell for a huge amount, and the buyer will be an individual (or a museum or a corporation). But for an author to earn a similar amount, she has to sell to a large number of individuals because each copy of her book is pretty cheap. Given this, one would expect the art criticism to be qualitatively different from literary criticism, as far as their relationship to the market goes. Art criticism, for it to have a market effect, has to persuade or dissuade a small number of wealthy individuals to buy a very expensive piece of art, whereas literary criticism, to have a market effect, has to persuade or dissuade a much larger number of individuals to make a much smaller purchase. Very different dynamics, no?

As Suat said, the $12 Million Stuffed Shark claims (and I think demonstrates) that the art market (defined as auction sales, gallery sales, and private market sales) is not effected by criticism. This was humorously confirmed in Hyperallergic’s annual “20 Most Powerless People in the Art World” feature. They wrote: “17 — Negative criticism. Dan Colen’s supposedly sold-out show at Gagosian proves that bad reviews have lost any semblance of power.”

But this is a simplistic reading. A lot of writing about art favors art that is not easily collectible. Art that is socially engaged in some way, or conceptual. Critics like installations and process art and “social sculptures.” Some of this ends up in galleries, but it is pretty hard to sell compared to paintings and sculptures and photographs. Collectors, not surprisingly, prefer “things” to “processes” or “ideas”. This, I think, is one of the main reasons that art criticism is not relevant to art buyers. Collectors aren’t going to buy your endurance performance, so they don’t care what the review says about it, so they look elsewhere for signals about what art to buy. There is an art-buying consulting industry that serves this purpose. (We’re talking about for very high end art, here.)

That said, it doesn’t mean those art critics don’t have power–just not in that market. There are foundations and institutions that do pay for brainier, more abstruse works. Here in Houston, for example, there is a foundation called the Idea Fund, and every year it gives out grants primarily to artists who are creating art that, by its nature, simply cannot be sold. At least, not very easily. This kind of grant-making foundation may be very interested in what critics have to say. But this kind of activity–giving grants to artists–is not usually considered part of the “art market” (wrongly in my opinion). So whatever influence critics may have with these institutions is not considered when it comes to speaking about market influence.

“is not affected by criticism” not “is not effected by criticism”. My apologies to the letter “a”.

I have a friend who works in an art consulting firm, helping corporations and very wealthy individuals purchase stuff to put on their walls. It’s kind of a depressing job.

Two parenthetical comments:

a) Welcome, Robert Boyd. I’ve read your articles for years, to my intellectual profit. I hope you’ll comment often on HU: we often discuss matters that interest you.

b)Commercially, there’s an interesting tension between scarcity and abundance. Sometimes those who manage an artist’s career will create artificial scarcity (e.g. limited edition prints.)

Sometimes they will insist on abundance: I remember one 1980’s Soho gallery owner stating that she would never consider exhibiting any artist who couldn’t create 40 paintings per year– enough for an annual show. (This was in a go-go decade for contemporary art.)

So if a painting takes you more than a week and a half, you’re fucked.

Scarcity: market manipulation. Abundance: productivism.

What would Adorno make of the so-genteel art business?

One acquaintance of mine gets flack for the opposite reason; he’s so prolific that his gallery keeps telling him to slow down.

Art in a capitalist society, in whatever form, is going to be closely involved in capitalism. Even vigorously denying one’s own marketability ends up being a marketing tool (as Tom Frank has discussed.)

Noah:

“I have a friend who works in an art consulting firm, helping corporations and very wealthy individuals purchase stuff to put on their walls. It’s kind of a depressing job.”

Oh, why? Artists have depended on patronage forever. The Medicis were a bunch of pawnbroking commercial thugs, you know. So what?

There was a fascinating article in ‘Time’ magazine this year about banks’ art collections. Deutsche Bank, for instance, owns over 50 000 items and employs six full-time curators. This is by no means atypical.

40 paintings a year is still not mass production. A book is a mass-produced item that, unless it is a limited edition, is produced up to what the market is willing to buy. But your gallery owner is onto something that affects prices for comics art as well. If we imagine markets at their most simple, they are determined by supply of the stuff (art in this case) and the demand for it. In our case, the stuff is not a commodity–each individual item is unique, even though it is related to other individual items. A given Peter Doig painting is similar to but not identical to another Peter Doig painting, and an Adam Hughes sketch is similar but not identical to another Adam Hughes sketch. The differences, however, can add up to a lot of money.

But still, the buying habits of the market are important. Demand is not static. Your Soho gallery owner wanted a show every year because too long a delay between shows will allow collectors to possibly lose interest in the artist. The annual schedule reminds collectors about this artist that they had previously liked. (The same dynamic is present in the readers of thrillers–thriller readers want their new Michael Connelly or Janet Evanovich novel every year. This annual output is practically a prerequisite for success for thriller writers.)

The same dynamic works in comics art auctions. Let’s say you want to sell 250 pages by a given comics artist. The way to increase your prices is to put one up for auction every week or every other week. Buyers (and therefore “demand”) often respond to frequency. Each auction, each new gallery show is a reminder to potential buyers that this artist exists–and that’s the first hurdle to cross in making a sale.

Alex: I think any time where you take something you love (art, for example) and turn it into your job (being an art consultant), you take on the risk of draining the thing you love of any joy it once had for you.

It’s a depressing thing to do if you care about contemporary art. My friend does; the people who buy the art generally don’t so much.

Suat-

A timely post by cartoonist Gabby Schulz, tangentially related-

http://www.gabbysplayhouse.com/?p=1410&cpage=1#comment-2011

Liked the post, by the way!

I read the first bit of that Sean…that really irritates me. Warhol is funny and smart and really an interesting artist…and, you know, it’s not like he invented the commodification of art, which has been around probably since there’s been art, or at least since there’s been capitalism. (John Berger’s pretty convincing on that).

Noah- I figured it might :) If it makes you feel better, there’s some further discussion in the comments that clarifies/softens the Warhol commentary a little bit. I agree with one of the commentators that the problem wasn’t Warhol- he was a playful commentator (and user) of the market. The problem is seeing Warhol’s innovations as virtues instead of commentary on a flawed system.

Also, I just used some variation of the word comment five times in the above four sentences…

Also, here’s a link to the post itself instead of my asinine comment. Not sure how I got that wrong before….

http://www.gabbysplayhouse.com/?p=1410

But Warhol’s innovations are virtues! I just saw a pretty entertaining show that was very pop art influenced; it was trashy and shallow…but also engaged and weird and kind of scary. I don’t know; I think comics just have a grudge against pop art because it was influenced by comics but it’s better.

>But Warhol’s innovations are virtues!

Virtues because the statements themselves are important, or virtues that should be emulated by the entire art market? You can’t blame all the faults of the modern (as in current) art scene on Warhol, but certainly by taking those excesses to their logical conclusion he helped usher in the decadent, and in my estimation, emotionally bankrupt, era that we exist in now.

As for this- >I think comics just have a grudge against pop art because it was influenced by comics but it’s better.>>

I’m not even sure how to respond to that. An entire medium weighed against a transitory, commentator-defined movement? Isn’t that like saying that slasher movies are better than sculpture? Let’s say we can go through your house and your memory and erase selectively- would you rather have every memory associated with Warhol, Lichtenstein, Koons, etc. or every single comic you’ve ever read/encountered/been influenced by?

I definitely understand the importance of Pop art- but once the point’s been made, the barrier has been broken, what, then, becomes the point? Does someone purchase a Warhol print for the actual object itself, for some aesthetic quality to it, or are they purchasing it for its proximity to the real object, the famous subject or artist? And more importantly, is this really the mode by which all other future visual art should be created, purchased and engaged with?

Back to the post in question, I found the ending very stirring. Surely a liberal quotation is in order-

“Sometimes when I’m losing perspective on my own work, I like to play a game where I imagine Art Historians of a far and distant future unearthing our work, and judging us Comics Artists of the Late Globalization, Post-post-post-post-Modern, Pre-Apocalypse period with the benefit of hindsight. “Fascinating,” they’ll usually say. “These primitive artists had a marked fixation on this video-game plumber guy. And teenage vampires figured strongly in the iconography. But what’s odd is, we see very little attempt to fashion even these apparently useful cultural totems into a valuable comment on anything about the culture itself. Art, it seems, is failing here to be art! And this flight from social engagement almost resembles a sort of hypnosis. It’s as if some outside force — perhaps the ‘ornamental culture’ of the early 21st century — has divorced even these ‘artists’ from their own proto-identities. They devolve into mere indulgence-replicators, and as such lose one of the only innoculations against those forces which manipulate and enslave them. It’s unnervingly machine-like. Surely it is no coincidence that, directly following this time of willing prostration to commerce and hindbrain greed, we see a rapid dissolution of their cultural framework, a sharp rise in fundamentalist religions, depletion of their ecosystems, and a fervent warmaking, followed by economic collapse — whereupon we enter Western Civilization’s second great Dark Ages. Mmm. Sure glad we weren’t born then!“

Robert: “Let’s say you want to sell 250 pages by a given comics artist. The way to increase your prices is to put one up for auction every week or every other week.”

Interesting. It does appear that Jaime Hernandez and Todd Hignite are taking this advice to heart with regards the former’s original art. Seems to have worked so far but it does create the impression of an “endless” supply of art which, in turn, might lead buyers to delay purchases until just the right piece appears.

Sean: Looks like Gabby’s Playhouse is down but managed to read the article (but not the comments) through Google cache. Might be because of the large bandwidth eating Kate Beaton-related cartoons posted recently. The comparisons to the slave trade don’t seem appropriate but it’s only a side issue in that article.

Noah: The comics vs pop art thing has been around for ages. More to do with perceived “stealing” than any real influence. I remember an article in The Comics Journal (mid to late 80s) “provocatively” suggesting that Lichtenstein was better than the artists he “stole” from . Reached a head with MoMA’s High and Low (1990?)and now seems dead in the water as a real issue. Both comics and contemporary art have moved on. Having said this, I find Warhol limited as an artist. He’s not someone I can return to over and over again, and not remotely close to being a favorite across all media.

On a side note, the Guardian reviewer of Sarah Thornton’s book engaged in a bit of handwringing concerning the Murakami section of “Seven Days in the Art World”. The strange thing is that Murakami comes off looking quite good in Thornton’s book in my opinion, at least compared to the other artists mentioned. Much more versatile and concerned about the final product, as well as stressing the collaborative aspects of his work. Took the mickey out of his dealers though.

Sean and Suat; I’m not a Warhol expert or anything, but I tend to really enjoy his work, and I find pop art in general moving, entertaining…all that good stuff. I saw a Lichtenstein exhibit a while back and it was lovely and weird and very enjoyable.

I think in general visual art is in a way, way better place than comics aesthetically. There’s much more room for experimentation, much more openness to other traditions and other art forms — dance, architecture, music, video, comics, community organizing — really, anything can be art. I find that exciting and invigorating, and it seems to me to produce a lot of amazing and bizarre work.

I mean, yes, visual art can be a wasteland too, and it is certainly more than neck deep in capitalism. But comics folks sneering at Warhol because his innovations are passe — what exactly has comics learned from Warhol? I guess the Fort Thunder people have picked up on his use of icons and on some of his color sense. But in general the primacy of the concept, and the way he negotiated between high and low art — Raw looks really clumsy and self-conscious in comparison.

Also, slasher movies are better than sculpture. I have spoken.

Noah: Saying that visual art is in a better place than comics aesthetically is a bit like saying that literature is in a better place than comics. Who would think otherwise? (I say this in the full knowledge that you hate tons of contemporary American literature)

Are you responding to something in the comments section of that Gabby’s Playhouse article, the ones I can’t read? Can’t blame all of comics for some stray comments in the blogosphere. Your detractors will be happy to learn that your taste in contemporary art is much more conventional than your taste in books, movies and comics (as is your penchant for defending its icons; icons who clearly don’t need any defending). Finally, an area to connect with… :)

I feel like I”ve seen comics folks run down pop art before, I guess. And bashing Warhol just in general seems like a thing. But I’d defend Nabokov too if called upon to do so! (Or Charles Schulz for that matter.)

I’ve not really been following the Warhol debate here, but… doesn’t Warhol’s use of mass and factory type (re)production help pave the way for seeing comics as art in some sense?

Noah,

Many fanboys hate/resent Lichenstein for appropriating Ditko and others. Lichenstein could be pretty condescending of his sources, viewing them as something akin to found objects.

Derik,

I once started a thread about that very thing. Not much discussion occurred, but you’ll probably find the links interesting.

Huh. That’s pretty interesting. I don’t know enough about the history to know if Warhol’s ideas about the artist actually helped solidify the idea of comics as art or not. My guess would be no…but I could really be wrong…..

I always leave off the ‘t’. Anyway, I can’t find an interview with Lichtenstein that I read where he’s really dismissive of comics art, but I did find Spiegelman saying, “Lichtenstein did no more or less for comics than Andy Warhol did for soup.”

My guess lines up with yours, Noah, but I think one might find a defense in Warhol’s ideas, as expressed in that article I linked to in the link.

I like that Spiegelman quote because I think you could argue that Warhol did a lot for soup (or more specifically advertising.) He made it art!

Okay, read the whole thing now.

It seems really confused. Basically, it’s setting up a binary between high-art as consumable and low art as honest/outside consumption. That’s patently ridiculous; if high-art is consumable, low-art certainly is as well. The exact mechanisms of the consumption are different, but to call comics the last honest art form (or whatever he says precisely) is pretty idiotic.

Also, earnestness is every bit as consumable as irony — sometimes more (self-help books aren’t notably ironic.)

>>I like that Spiegelman quote because I think you could argue that Warhol did a lot for soup (or more specifically advertising.) He made it art!

See, that’s the nub of the issue as far as I’m concerned. That’s Warhol’s (and “Pop Art”‘s) trick, his innovation, IMHO- art is what we put on walls. Or, in his formulation “art is what you can get away with.” But when he’s doing it, in the context of the time period, it’s a naughty, rebellious act that transformed some people’s opinions about the designs or images he was “appropriating”. But once that statement has been said, how much farther does it need to be taken? Is Jeff Koons required in this world? Add to this his more market-driven innovations (mass production with carefully orchestrated roll-outs and artificially limited supplies, and thematic justification for such) and you have many of the problems plaguing the visual art world today.

So, no, I don’t blame him. But certainly he is the model from which many of the contemporary art world issues arise.

That’s not Warhol, though (the anything is art bit); it goes back to Duchamp at least doesn’t it?

>>>The exact mechanisms of the consumption are different, but to call comics the last honest art form (or whatever he says precisely) is pretty idiotic.>>>

But he also tears down comics as they currently exist- i.e. the last paragraph I quoted earlier. It seems to me he’s not saying that the honesty is necessarily a good thing, or borne out of any fundamental straight-forwardness- rather that this most recent wave of cartoonists have not been successfully commodified and can therefore do whatever they’d like to, so why not do something worthwhile?

>>>Also, earnestness is every bit as consumable as irony — sometimes more (self-help books aren’t notably ironic.)>>>

Heh. This is my beef with most non-fiction books, by the way.

No, you’re right- Warhol is taking Duchamp’s idea and running it across the goal posts. Although I suppose Koons could really be the logical extension of Warhol- why not eliminate EVERY potentially expressive element and essentially have a large, shiny copy of whatever you’re appropriating made for you in a factory? Hm. The sheer mindlessness of that does have it’s own appeal.

I think that’s somewhat confused though; contemporary cartoonists are commodified. The issue isn’t that they’re out of commodification so can do something interesting; the issue is that they need to figure out how to do something within the terms of their commodification. That’s why Warhol’s interesting; he took the terms of the art market that he was in and made it part of his art.

I’d say the takeaway from Warhol isn’t to make art like Warhol, but that understanding the market you’re in and thinking about that is vital for making interesting art. And simple binaries aren’t useful for doing that (I’d argue.)

>>>The issue isn’t that they’re out of commodification so can do something interesting; the issue is that they need to figure out how to do something within the terms of their commodification.>>>>

Yeah, I see your point here, and I definitely see how this aligns with a lot of your interests (Wonder Woman popping to mind- surely the super hero is one of the unlikeliest venues for self-expression, but there you have it…) Of course, the less money involved, with the less overhead, comes a commensurate level of freedom to work out your own personal quirks and interests, without anyone there to tell you no.

>>>>I’d say the takeaway from Warhol isn’t to make art like Warhol, but that understanding the market you’re in and thinking about that is vital for making interesting art.>>>>

Please build a time machine and go tell this to virtually every critically and commercially successful visual artist working in the eighties. Snark aside, I concede the point.

“Of course, the less money involved, with the less overhead, comes a commensurate level of freedom to work out your own personal quirks and interests, without anyone there to tell you no.”

This is really tricky though. Working for no money is often as much of a cage as working for a lot of money — often more really…..

>>Working for no money is often as much of a cage as working for a lot of money>>

You don’t have to tell me! How’s about very little money? I’d like to start working for very little money…