“I bet one legend that keeps recurring throughout history, in every culture, is the story of Popeye.” —Jack Handey

Popeye was pretty far removed from his Golden Age when I was first introduced to him, probably through some combination of Hanna-Barbera’s The All-New Popeye Hour (1978-81) on Saturday morning television, whichever Famous Studios shorts were packaged for syndication at the time, and the various coloring books and toys that piled up around our house. This was a Popeye who rarely hit Bluto, was a doting uncle to his nephews Peepeye, Pupeye, Pipeye and Poopeye (Huey, Dewey and Louie got off easy, didn’t they?), and was pretty much a total chump unless he managed to down some spinach, which always happened just about a minute before the cartoon ended.

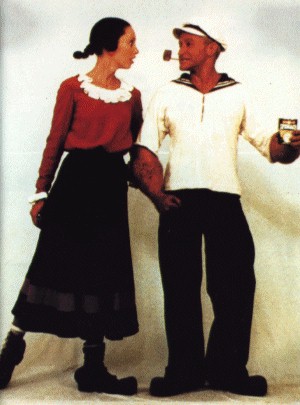

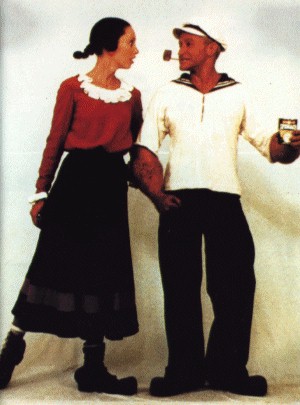

Despite these shortcomings, I was a dedicated Popeye fan, and could draw a fair likeness of the character before I could write my own name. I’m not sure when I first heard about the Robin Williams Popeye movie, but I do remember it feeling like years for it to reach our local theater (and it probably did take the better part of a year for it to reach our second-run movie house), and I remember being blown away when I finally saw it, all of five years old at the time. Great scenery, great actors, great characters, fun songs—and Robin Williams as Popeye and Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl are still two of the best-cast live actors-as-cartoon characters in movie history.

Jules Feiffer’s goal with his screenplay was to pay tribute to E.C. Segar’s original comic strip, with a back-to-basics approach. Popeye was an unpredictable tough guy, Bluto was a creep, Wimpy was selfish, and Olive was so fickle that you really had to wonder why people were trying so hard to impress her. Toss in Poopdeck Pappy, who was an out-and-out bastard, and you had some of the greatest characters in comic strip history. (Well, not Bluto, who only figured prominently in one Segar Thimble Theater storyline, but I’m sure we’d have seen more of him in the comics eventually.)

So what was the end result of this return to Popeye’s roots? Underwhelming box office, immediate attempts from Robert Altman and Robin Williams to distance themselves from the picture, and a relaunch of the Saturday morning cartoon which included Olive Oyl and Alice the Goon in a shameless Private Benjamin knockoff. As if that weren’t enough to kill off these characters, four years after that, Popeye and Olive were married off and settled into suburban life in Popeye and Son, a premise which turned me off so much that I never watched a single episode.

There were signs of life along the way, however. Fantagraphics’ reprint series The Complete E.C. Segar Popeye ran from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, which roughly matched up with underground cartoonist Bobby London’s tenure on the strip. While I was sadly oblivious to Popeye’s print adventures, the rise of cable television and the need for cheap programming meant that Ted Turner was filling about six hours every day on each of his networks with old cartoons, and the Fleischer Popeye cartoons featured heavily in the rotation, with nary a Famous Studios or a Gene Deitch Prague-produced Popeye to be seen.

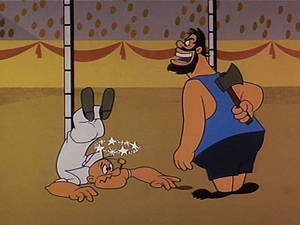

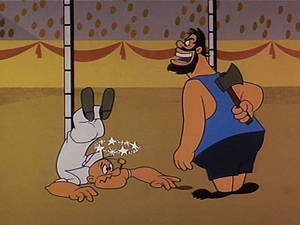

The early Fleischer cartoons were even better than the live-action film, with random acts of violence, oddly synched vocal tracks which didn’t match up with the characters’ on-screen speech, and the broad personalities which made Segar’s characters popular in the first place. Popeye always tries to do the right thing, whether he’s capable or not; Bluto always tries to stop Popeye, whether he should or not; Olive’s out for attention, whether she deserves it or not; and Wimpy could care less, as long as his stomach’s full.

Watching the earliest Popeye cartoons again in preparation for my contribution to the roundtable, I was struck by just how much care and effort the Fleischer studios put into them. Popeye was incredibly popular with American audiences when the first animated cartoons were released, and the Fleischers probably would have cleaned up with an average or even subpar product. But they put their best crew on the job, wrote some great songs, cast some brilliant voice actors and created some classics that are still fun to watch more than 70 years later.

But better still, better than Robin Williams on the big screen, better than Jack Mercer and Mae Questel voicing the Fleischer cartoons, better than all of that were Segar’s original strips. One of the great pleasures in being a comics fan is discovering something new and unusual, unlike anything you’ve ever seen before. And even better, in my book, is finding out that the original incarnation of a favorite cartoon or comic was significantly better than the stuff that you thought you’d been enjoying. I experienced that by going from Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends in the early 1980s to Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s Amazing Spider-Man reprints in the late 1990s. I’m pretty sure that Chris Claremont’s late 1990s version of the Fantastic Four was hitting the stands around the time that Marvel decided to issue the Essential Fantastic Four collections, reprinting the original series by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. And my main exposure to Plastic Man before reading Art Spiegelman’s New Yorker article on Jack Cole was the Ruby-Spears animated series of the early 1980s, Hula-Hula and all.

And I had the same reaction to Segar’s strips that I had to the aforementioned examples: “Where has this been all my life?”

Since I can’t (as yet) go back in time to drag my younger self away from The All-New Popeye Hour, Pac-Man and The Snorks and beg myself to read Segar’s Thimble Theater instead, there’s still time to save some of the unitiated out there. If you’ve only seen the Popeye animated cartoons, and God help you if you actually watched Popeye and Son, pick up one of the Segar reprints as soon as humanly possible. Start in the mid-1930s, when Popeye finds his long-lost father (and finds out that he should probably stay long-lost). Or when Popeye takes over a local newspaper, and decides to spice up the headlines by beating up townsfolk and blowing his entire payroll on staff cartoonists. Or the time Popeye becomes “dictipator” of a small island nation. Or the fact that Popeye’s first plan of attack in any complicated situation almost always involves him dressing in unconvincing drag, which is guaranteed to fool his intended target.

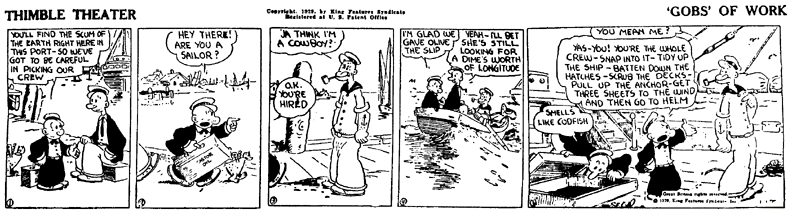

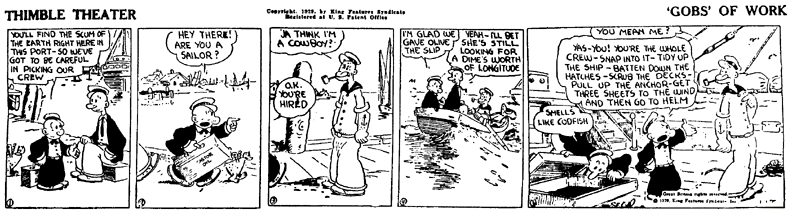

Or better yet, dive right in at the beginning. “’Ja think I’m a cowboy?” is still one of the all-time great first lines of any cartoon character ever, and it still holds up 80 years later. Segar grows as a storyteller by leaps and bounds throughout the 1930s, and it’s easy to see why just about every cartoonist who grew up in that decade worshipped him. Thimble Theater is one of those rare strips from the early 20th century that I don’t need to qualify with “it’s pretty entertaining for its time,” or “you have to remember that humor was different then.” Popeye’s mangling of the English language (and his mangling of people) is as entertaining now as it was during the Hoover administration, and that’s why his legend endures. It’s a real testament to Segar’s original work that no amount of terrible animation, kid sidekicks and general neglect can keep a good sailor down.

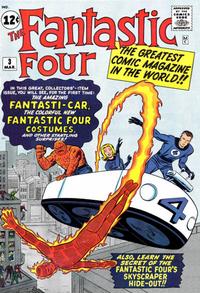

On the cover of the third issue of The Fantastic Four, published in early 1962, Marvel proclaimed it “The Greatest Comic Magazine in the World!!” That’s a bold statement, but, as Dizzy Dean once told reporters, “It ain’t bragging if you can back it up.”

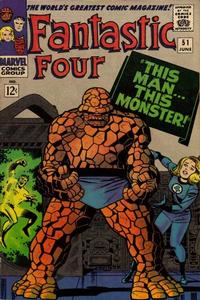

On the cover of the third issue of The Fantastic Four, published in early 1962, Marvel proclaimed it “The Greatest Comic Magazine in the World!!” That’s a bold statement, but, as Dizzy Dean once told reporters, “It ain’t bragging if you can back it up.” Lee and Kirby’s The Fantastic Four had adventure. It had humor. It had romance. Pathos. Wit. Charm. And frequently all within the same story. The Fantastic Four #51, “This Man, This Monster,” is probably the single greatest Marvel comic of all time. Which follows one of the great three-part stories of all-time, “The Galactus Trilogy.” Which really benefits from reading the Inhumans story that leads into it. And it would be a shame not to keep reading forward with the two-parter that introduces The Black Panther. And for gosh sakes, that’s only a stone’s throw from the ultimate Silver Surfer vs. Doctor Doom battle. There’s a good 20-issue run of nothing but high points once Joe Sinnott starts inking, too, although there’s a fun, anything goes atmosphere to the first issues, right out of the gate.

Lee and Kirby’s The Fantastic Four had adventure. It had humor. It had romance. Pathos. Wit. Charm. And frequently all within the same story. The Fantastic Four #51, “This Man, This Monster,” is probably the single greatest Marvel comic of all time. Which follows one of the great three-part stories of all-time, “The Galactus Trilogy.” Which really benefits from reading the Inhumans story that leads into it. And it would be a shame not to keep reading forward with the two-parter that introduces The Black Panther. And for gosh sakes, that’s only a stone’s throw from the ultimate Silver Surfer vs. Doctor Doom battle. There’s a good 20-issue run of nothing but high points once Joe Sinnott starts inking, too, although there’s a fun, anything goes atmosphere to the first issues, right out of the gate.