The index to the entire Joss Whedon roundtable is here.

_________

How do we define “authorship,” anyway? Even in this age of endless reboots, remixes, and universe-building, there’s still some kind of value placed on the idea of originality, as there has been all along. Whether it’s Dickens’ attempts to tighten copyright law in order to shut down rogue performances of his work, JK Rowling’s attempts to shut down publication of a Harry Potter encyclopedia, Warner Bros. forbidding Rocky-Horror-style viewings of “Once More with Feeling…”, or countless post-finale interviews with showrunners offering the “right” interpretation of their show, the relationship between a reader and an author is largely defined by power and anxiety. Sometimes they’re protecting their money, but more often than not, especially in the case of flesh and blood writers like Dickens and Rowling, they’re guarding the sanctity of something more ineffable—something that gets at the etymological root of “authority.”

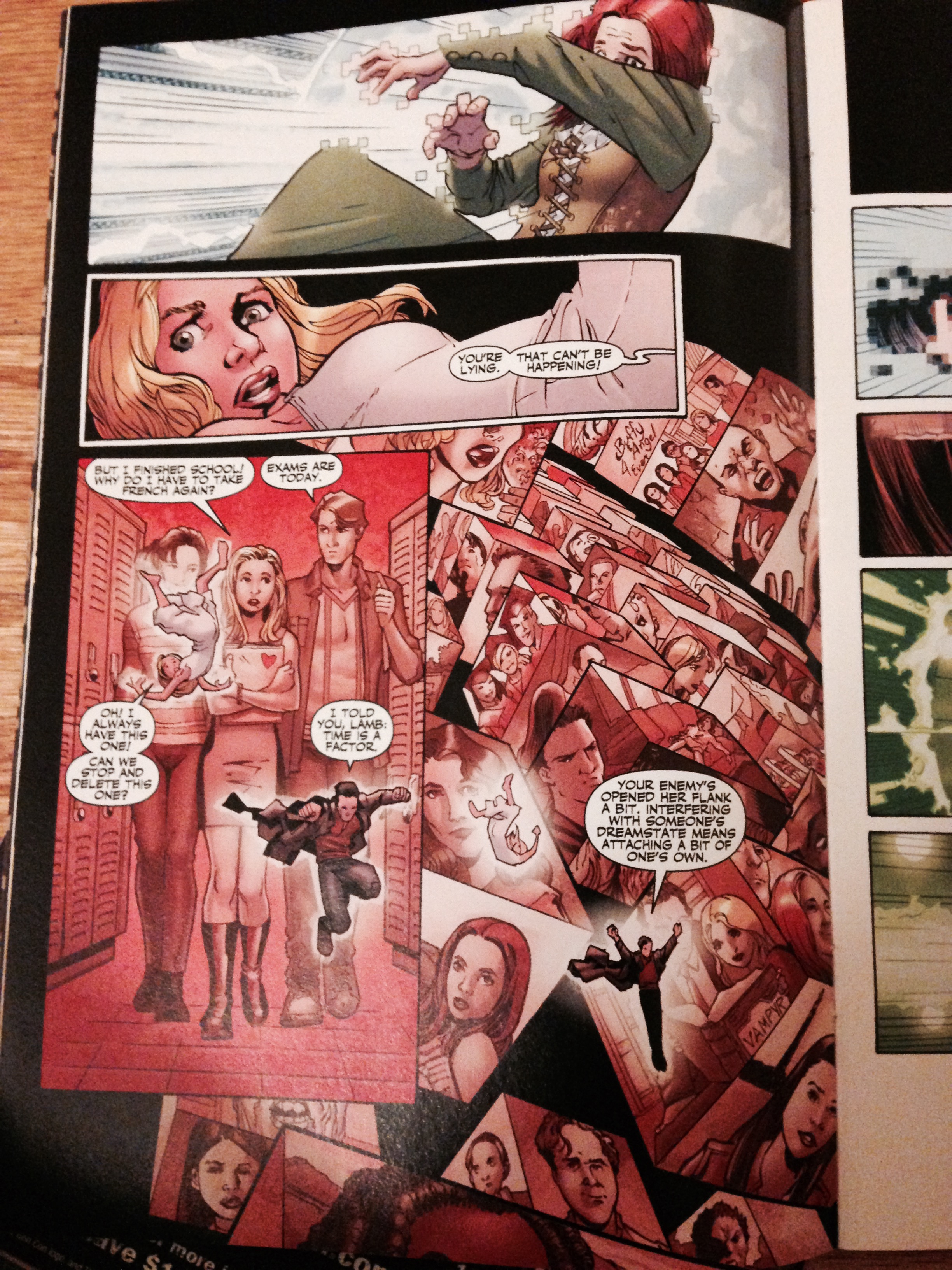

As auteurs go, Joss Whedon has never overtly demonstrated too much of this kind of anxiety. From the beginning, he’s positioned himself as a fan among many, but a kind of super-fan. He engages in projects that feel like fan fiction, recasting Dracula as a minor player on the Sunnydale scene, rewriting space opera from the position of the colonized in Firefly, continuing the story of Buffy in comic form, and even including his own image in a panel of Buffy’s dream sequence–look at the bottom of the page below. It’s Mary Sue through the looking glass!

Perhaps even more importantly, Whedon’s let fans behind the curtain of the production process, participating in early fan forums such as The Bronze and Whedonesque, and even going so far as to hire fans such as Drew Greenberg and Michelle Trachtenberg in later seasons of Buffy. When “authority” has influenced the direction of a text, Whedon’s always positioned himself as being on the side of fans–Fox stunted his vision of Firefly, Warner Bros. didn’t appreciate him enough to give his actors ER or Friends-level salaries, Fox hamstrung the development of Dollhouse, etc. Even his more recent, high-profile work within the Marvel franchise is so rooted in his own fandom that the difference between “adaptation” and “fanfic” gets hard to parse. It’s no wonder fans refer to him as “Joss”–he spent a lot of time and energy, especially early on, cultivating just that kind of intimacy.

But it’s important to remember that this intimacy was always charged with hostility. Jonathan Levinson on Buffy is probably the best example of this vexed closeness. In “Superstar,” for instance, Jonathan gets the intimacy that being on a first-name basis with Joss Whedon might lead to (included in the credits, influencing the rest of the plot of Season Four), but his desire for too much closeness, too much control, is what turns the other characters away from him at the end of the episode, and lays the framework for his return in Season Six as one of three Bad Fans. It’s common enough to have figures of bad fans in a text serving as negative examples of Reading Gone Wrong–the Trio has good company in Ben Linus on Lost, Silas Wegg in Our Mutual Friend, Felix Gaeta on Battlestar Galactica, Comic Book Guy and countless others. The thing that’s interesting to me is how, in “Superstar,” Jonathan’s “bad” fandom doesn’t look that different from the “good” fandom that came from all the people Whedon had been palling around with on The Bronze and Whedonesque. This relationship to authorial power–the boss who’s also your buddy–is ultimately unsustainable, and that’s where the vitriol behind the depiction of fans in Season Six of Buffy comes from, I think.

Which brings us to the present day, and Whedon’s decision to quit Twitter. In his recent interview with Buzzfeed, he blows off the idea that feminist blowback to the Black Widow storyline drove him from Twitter. To his credit, he’s pretty blasé about the whole thing, pointing out how much worse it is for women on Twitter than it would ever be for him. What struck me upon reading the interview, though, was how his reasoning had less to do with politics than it did with intimacy. Twitter is an intimate medium, and the intimacy comes with very little effort on either side. For instance: when I was writing my dissertation (which partially focused on Buffy, natch), I was following television writer and producer Jane Espenson on Twitter, and every now and then she’d announce a “writing marathon,” encouraging her followers to tweet how much they’d written. I didn’t mention her on my acknowledgements page or anything, but those goals felt supportive, and kept me on track toward finishing. I was never part of those early Bronze chat rooms, so I’ve always been a little put off by calling Joss Whedon “Joss,” but when I was writing my dissertation, Jane Espenson did feel like “Jane.” Twitter can feel like a place where you’re hanging out with your friends (shades of The Bronze, perhaps), but when it turns, it turns fast and hard.

With a property as big as The Avengers, the intimacy that characterized his early work just isn’t sustainable anymore, and that’s what his retreat from Twitter is about, I think. Like many others, I was pretty put off by the “big reveal” of Natasha Romanova’s sterilization backstory, and especially by her line that infertility made her a “monster.” I found myself making excuses for Whedon in my head, almost right away, since this seemed so different, at first, from choices he’s made in the past (except, of course, for that one episode of Dollhouse). If it were from anyone else, would I have been surprised by such a hacky motivation for a central female character? Getting depth for female characters in summer blockbusters is always tricky, especially for writers working within an established franchise. But because of my love for Buffy (and Angel and Firefly and Dr. Horrible and even Dollhouse) my expectations are higher, and my disappointment proportionally greater. Based on the tone of some of the responses, I’m not alone in my feeling that this cinematic disappointment is more personal than others.

But here’s the bind for Whedon: his “betrayal” isn’t as personal as it feels, because there’s just no way that he would have the same kind of control over the content of something like The Avengers. Nor can he position himself as a creative genius, hemmed in by the forces of an evil corporate Big Bad. He’s too close to this Big Bad, and his position is much more precarious–Dan Harmon and Amy Sherman-Palladino excepted, it’s rare for a showrunner to get booted from the fictional world s/he invented (and Community and Gilmore Girls both serve as cautionary tales for doing so). But The Avengers is different–he could get replaced on this project easily, though, so his old “I’m on your side, it’s the goddamned network fencing me in” approach isn’t available.

Ultimately, Joss Whedon is too close to too much power (without actually wielding that power) to be the Cool Dad anymore, the one who “gets it” but has to exercise authority because he loves you. The project is too big, its influence too far-reaching for him to be able to hang out on message boards and kibitz with fans. Twitter offers the promise of intimacy, but Whedon’s fans have come to expect something that approaches the real thing. And as Cool Dads have learned since time immemorial, the closer you are aligned with the machinery of power, the less possible it is to be everybody’s BFF. Whedon will just have to settle for being one of the richest guys in Hollywood.