There are two kinds of people in the world, my father used to say: People who divide all the people in the world into two types and people who don’t.

Comics readers tend to be the former: They look at the world as made of up of the initiated, people who read their particular type of comic (be it superheroes, shoujo manga, or introspective graphic novels) and those who are outside the walled kingdom.

There is some validity to that, because most comics genres, like most other genres, require a certain initiation. In the case of superheroes, you almost have to be born into it; one could spend a lifetime learning all the backstories, interrelationships, and alternate universes. Manga readers have to learn a code of visual cues such as sweatdrops and cultural clues such as honorifics and holidays, not to mention how to read right to left.

People who don’t normally read comics, on the other hand, don’t usually define themselves as “people who don’t read comics.” Most, in fact, will pick up a graphic novel if the subject matter interests them. They might not be able to enjoy something very genre-bound like Blackest Night or Battle Angel Alita, but they might read Fun Home, Mom’s Cancer, or The Photographer, because those books tap into more universal experiences and interests. A lot of people read those books not because they are comics (although the medium may make the story more compelling) but because they are books.

A lot of literary manga deals in topics that adult readers are interested in: Oishinbo (gourmet food), Ooku (historical drama and switched gender roles), Suppli (workplace comedy and romantic angst). These are good stories about things people care about, and you don’t have to understand the intricacies of samurai life or the Japanese school system to enjoy them.

But before you can read them, you have to find them.

Noah asked us a simple question: How do you market art manga to readers? The answer is equally simple: Don’t market it as manga. Market it as books.

Some specifics:

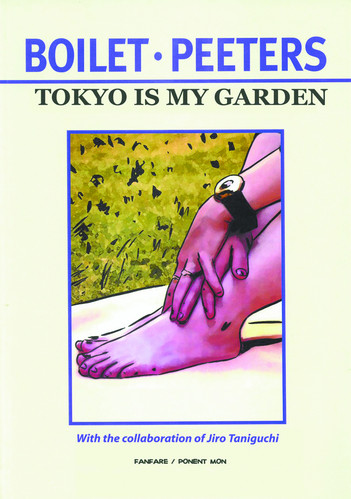

Don’t shelve it in the graphic novel section: The first step in reaching that broader audience is not to confine the manga to comics stores or even to the graphic-novel section of the bookstore. Ideally, booksellers should keep a couple of copies around, some in the graphic novel section and some elsewhere: Put Oishinbo near the food section, Barefoot Gen near the World War II books, Suppli by the chick-lit, Naoki Urasawa’s Pluto next to the science fiction. Scatter a few literary fiction titles (Tokyo Is My Garden, Red Snow) among the “staff picks” novels in the center tables.

Flip it: The purists hate this, but for older readers, reading “backwards” is a deal-breaker. Furthermore, it marks the comics as manga, and for those who aren’t famliar with the medium, that starts a whole chain of associations: porn, big eyes, teenage girls, boobs-n-battles. A lot of readers, wrongly, think of manga as a genre; manga for grownups must be marketed separately from the shonen and shoujo teen fare. Titles with broad crossover appeal should be made accessible to all readers, not just the cognoscenti. You can always publish an unflipped deluxe edition for the hardcore otaku.

Hire Chip Kidd to do the cover: Or someone like him. Make it arty and attractive. Do not fill it with slashing shonen battle action or an upskirt shot of a schoolgirl. (If those things appear in your manga, you probably shouldn’t be marketing it to adults anyway.) This should be a book you are proud to be seen reading on the subway, not something that would embarrass you if your boss saw it in your briefcase.

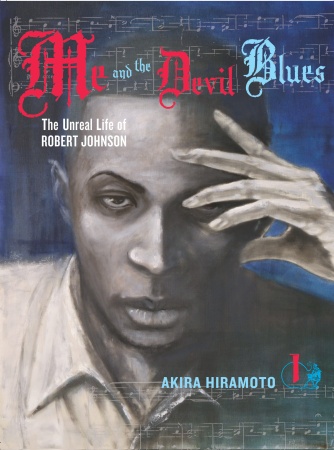

Send it out to “mainstream” reviewers: There are plenty of graphic novel-friendly reviewers at big newspapers and magazines, and they have a lot of pull. I first heard about Fun Home on NPR, and not because they were having “comics day” or anything; it just was a compelling story. As a journalist, I can tell you that a new and interesting topic is always welcome. A manga about a family with an autistic child? Bring it on! A manga about bluesman Robert Johnson teaming up with bank robber Clyde Barrow? Sign me up! These are topics that are interesting just by themselves, and the fact that someone in Japan has chosen to make a comic about them makes them even more interesting.

Also, you know what can really sell a title? Online previews at hip websites. There’s something inherently cool about manga, so the occasional free sample would most likely be welcome. Smith Magazine, for instance, hosted the webcomic AD: New Orleans After the Deluge, and Words Without Borders has a whole graphic lit section. These websites already cater to readers with a literary and artistic bent, so they are likely to be a receptive audience for art manga.

Go digital: You knew I was going to say that, right? Everyone is doing it! The Kindle, the iPad, and the plain ol’ internet are places your potential audience can discover your manga and instantly read it. Here’s the thing, though: Go ahead and put your manga into comiXology and Longbox and those other … things… but let them stand alone as well. Recently, Longbox developer Rantz Hoseley talked about the possibility of having a link directly from a story on, say, the NPR blog, to their digital edition of a comic. That’s a great convenience, but the occasional comics reader just wants to read the book, not sign up for some complicated digital storefront that they will never visit again.

Harness serendipity: All these factors boil down to the same thing: Make it easy for potential readers to stumble upon a book, and once you catch their interest, make it easy for readers to buy it. Go back to the dichotomy I started with: Serious comics readers know where to find comics and how to buy them, but it’s a system that is invisible to most people and forbidding to those who do know about it. Superhero fans may be willing to go out of their way to a special store and pre-order their comics sight unseen, but the rest of the world doesn’t operate that way. Even the graphic novel section of a chain bookstores is terra incognita to most customers. The key to expanding the comics market, for art manga or any other type of graphic novel, is to step outside the closed circle of the comics world and find the readers where they already are. After that, the books should sell themselves.

__________

The entire Komikusu roundtable is here.