This is part of a roundtable on copyright and free culture issues. You can read the whole Cuckoo for Copyright roundtable here.

=================================

Nina Paley’s adventures have taken her from Urbana, Illinois across the US and around the world to her current location in New York City, where I had the chance this past weekend to visit and talk with her about cartooning and copyright.

Paley worked as a cartoonist from the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, writing comic books and then newspaper strips before switching to animation. If you aren’t familiar with her work, check out her website and blog as well as my recent post about the copyright controversy surrounding her film Sita Sings the Blues. Or search for her cartoons on Archive.org.

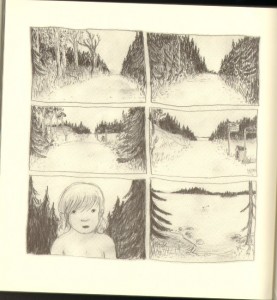

I was lucky enough to have a copy of a printed collection from 1987 of her very early work, from high school and college, which she hadn’t seen in years. That’s what we’re looking at during the start of this interview.

=================================

I’m looking at these political cartoons, and they’re really disparate. It looks like someone said “we’ve got this article on this thing; draw something.”

Yes, that’s exactly how the political cartoons in the Daily Illini worked. I was just an illustrator, I was just drawing. I developed my drawing skills long before I developed my voice. So I was happy to illustrate anything.

Did they tell you the position to take in the cartoon? Did you have to agree with what was in the article?

I don’t even think I was paying attention. [Stops and points to a particular cartoon.] God, what an idiot I was! This is such bullshit. I was developing my politics according to people around me, ‘cause I was in college. So I was just sort of – if anyone I knew was outraged about something, I would say “what are you outraged by?” and they’re my friends, so I was like, “that’s outrageous!” Now that I’m a grown-up, I’m thinking, “what the hell?” [laughter] All these — what the hell, these are all opposite to what I think now. Apparently this one was calling for more parking on campus, and I hate cars now, and there’s way too much parking and paving, screw that. And here: “the US isn’t doing enough about terrorism.” But I was so dumb then, “oh, these people are doing bad things to other people and we should do something.”

But you did come from a political family, sort of. Your dad was the mayor of Urbana…

He was the mayor between my ages of 4-8, something like that. It was all very traumatic. Not his being mayor, but the crap I got at school from other students. My thing was, I was drawing very early, and I had my own needs for attention and stuff, and every time I drew something well, the other kids would say “you’re just showing off ‘cause you’re the mayor’s daughter.” And I would be [crying] “That has nothing to do with my art!”

I was going to ask you when you started drawing; so it was really early. You mention (in the intro to the 1987 collection) that you did a couple of comic strips with a history professor at Uni High (University High School in Urbana). Were you cartooning before that?

Not much, I mean, I didn’t get into cartooning. I thought cartooning was not art. I aspired to draw “real art” when I was a kid, when I was below 10, I thought the goal was to draw as realistically as possible and that cartooning was some sort of weird cheating thing, or not cheating but just, it wasn’t the same. But then as I got a little older, got into my early teens, I realized that cartooning was powerful. It had a powerful affect on people that just drawing pretty pictures did not have.

Were you reading things that made you see it that way, or what caused the epiphany?

The epiphany was when I started drawing them and I got all this attention. I gotta be honest about attention. I’m thinking a lot about attention and the attention economy, and I am remembering attention is sort of a dirty word from my childhood, to say “yes, I wanted attention”, you’re not supposed to say that. You’re supposed to say that you have higher motives or something, but wanting attention is really bad. And of course it was always way more than wanting attention, but attention is an essential component of communication, you know? [laughs] There’s expression and then there’s reception, and reception or attention are sort of synonymous in that respect. So when I said things, I wanted to be heard. When I drew things, I wanted them to be seen, and I just found that if I drew cartoons, lots of people were interested in looking at the cartoons, and not so many people with drawing pretty. People would say, “oh, that’s very well drawn,” but cartooning actually had an effect on people; they would actually be engaged.

It’s intimate in a way that fine art is distancing?

I don’t know! I don’t think it has to be. It’s not like the drawings of a 13-year-old explored all the aspects of fine art [laughs] or anything like that. But even when I was into the realistic drawing, I was always interested in mass media art, like books, newspapers, illustrations. And I didn’t even realize – it wasn’t until I was almost 20 that someone distinguished illustration from art. I would make these drawings and someone said “oh, those are illustrations”, and I was “oh, there’s a difference? This is some category of art? I just thought they were art.” But apparently everything I was thinking was art when I was young was actually illustration; I just didn’t know that. I thought it was art.

That was when you were in college? Were you studying art?

I think I was about 19, and it was actually a cousin. A cousin of mine, Debbie, who is a really great artist and designer who now lives in Chicago. [Editor’s note: Debbie’s website is here.] She paints objects, like shoes – I mean she paints on them – shoes and chairs and things like that. She was a designer for a shoe company and they lived in Toronto, and I had drawn these ink drawings of iguanas and showed them to her and asked “What do you think of these? Can I be an artist? I want to be an artist!” and she said “oh, I think you’re an illustrator.” So apparently I must have been fascinated and influenced by books, comics, newspapers. Scholastic books, those books you order in school and they come like Christmas every month? They had all these great things that you can’t find online because they’re under copyright and whomever owned them would never release them that way.

I remember I had a book called Captain Ecology, a cartoon by Tom Eaton. There’s another cartoonist named Tom Eaton but this is a different one. It was a comic strip book thing and I liked the drawings. And there was Escaped from the Zoo in the Daily Illini; this would have been in the early 80s.

I always drew, everybody drew when we were young. Other people stopped drawing and I didn’t. It’s really true, everybody drew.

When did they stop?

I don’t know because I wasn’t paying attention! It was just like I looked up [laugh] and “what happened to everyone? When did this start?” I don’t know what age people start really getting into shame, like feeling ashamed of themselves.

[flipping through book] PLATO! (Editor’s note: PLATO was the first computerized instruction system, built around 1960 by the University of Illinois and used by the university and local schools.)

There are lots of computers, and engineering stories and space stories in this early work. Was that the influence of the people who were writing for you?

That was my group. My father’s a mathematician, and my brother was studying math and computer science; I went to Uni High after my hellish three years at Urbana Junior High. I used the PLATO computers all the time. I was an early computer addict before most people had that opportunity; those were my friends, that was my life. When I was in college, I met other people, but I didn’t befriend other people. I always thought that the cooler people were the engineers and stuff, I did study art and I dropped out after 2 years. socially going into the art department: it was like a wasteland.

So the transition to doing Flash animation on the Mac was very natural.

Yes! Definitely.

It sounds like you were very interested in expression, in getting your drawings out.

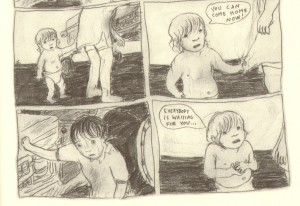

Initially, I was just interested in developing my skills. I didn’t really learn how to really speak with my own voice until I was 20 and moved to Santa Cruz and started doing Nina’s Adventures in Santa Cruz. Up until that point, I was just interested in illustration and illustrating other people’s ideas. It just didn’t occur to me that I had that kind of voice. And I just wanted to draw. I think I was aware of the power of drawing; I didn’t know how to use it but I liked it. I was developing it. I couldn’t imagine writing my own comic strip.

And I look back on it, and I had no self-esteem, so I was continually anxious about doing this comic strip that was written by someone who wasn’t a student, (Joyride, originally written by David Gehrig), because there were these really explicit rules: Student Work Only in the paper. So I had to keep it a terrible secret that I was using an outside writer – David is writing it and he’s not a student! I gotta write this myself, ‘cause I can’t have that!

You mention (also in the introduction to the 1987 volume) that you thought you weren’t a writer. How did you figure out that you could write them yourself? At some point you must have come to terms with yourself as a writer; can you tell a little bit about how you got there?

I just started! [laughs] OK, that’s not entirely true.

When I was 17–18, I started writing a journal. I was doing a lot of very necessary self-searching because I was depressed. I was quite out about being very depressed as a kid, and basically depressive as an adult also although I take medication; I’ve been taking medication for 20 years.

And it works?

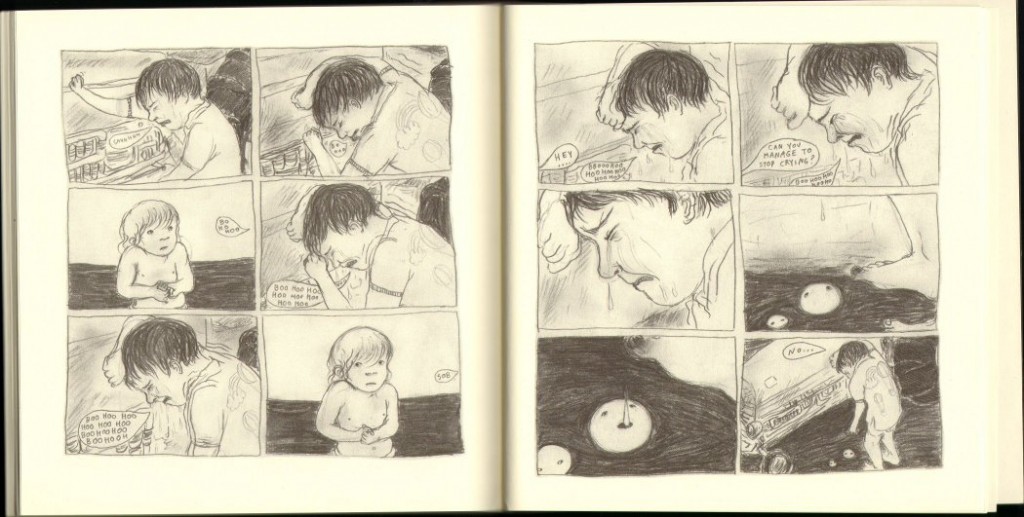

Yeah, fuck yeah. Which is not to say that I don’t still have episodes, but they’re spaced much farther apart. Devastating when they happen, but at least it’s not every day all the time. So, I was desperate, because that kind of mental illness, the older you get the worse it gets. So I was desperate for anything to help myself, and at some point I started writing this journal, this illustrated journal-y thing, where I was writing about real things that were actually going on. Things that I was feeling terrible about, and things that I was ashamed of, I would actually write them. I got better and better at looking at the hidden part of myself, and getting them out.

…externalizing them through both writing and pictures.

Yes.

Were those experiences of writing and drawing similar for you?

I wrote and drew.

Just seamless.

Yes. I wrote and drew pictures [laugh] of the inside of my head, punching people, killing myself, all those things. And they were funny, man, they were really funny. So I’d be writing these things and laughing.

And I saw shortly before I left Urbana, I saw Life in Hell for the first time, the Matt Groening books and I saw Lynda Barry’s older books. I mean, obviously they had to be older books because – that is what is now her early works. And both of them were actually doing comics about real things. They weren’t just doing fluff entertainment. They were doing psycho comics, and they were just so real. They were brilliant, and those were the first things, the first time I ever realized, oh wow, you can really discuss real stuff and deep stuff and profound stuff in comics, and be funny. So they showed me it was possible, and then I moved to Santa Cruz, when I was 20, which was a whole other world of trauma that I wasn’t prepared for.

Were you going to school?

Nope, I wanted to be a new-age crystal-wielding hippie. My friends in Urbana were hippies. In Urbana, the smart non-conformist people were hippies. And so I went to Santa Cruz, young and naïve, and was like, “oh, it’s all full of hippies; these are my people.” And I actually lived there, and then it was “no wait, in Santa Cruz, the dumb conformists are hippies and the smart non-conformists are something else.” [laugh]

So there I was – increasingly disillusioned, young, dumb, mentally ill, [laugh] and I’d just moved away from home, and I guess that was enough stress that it finally found an outlet with my Nina’s Adventures strips, which were taken from my journals, and so it began. Thus began my real life as an artist.

I was in Santa Cruz for 3 years, and then in 1991 I moved to Austin, Texas for 3 months, and it didn’t work out [laughter]. I had one hell of a depressive episode there. I kept moving away from anyone I had contact with. I didn’t realize that I actually had connections with people. I think that was a real problem with being depressed. There were people in my life but I felt like I was all alone, and nobody loved me and like that, so I thought I had nothing to lose, but you move away from it and it’s like, “oh wait, wait a minute, I did have friends, and [laugh] I’m calling them all long-distance now!”

Back before there was cheap long distance included with your cell phone.

Exactly. So then I moved to San Francisco because when I lived in Santa Cruz I’d met people who lived in San Francisco and I thought, “I’m just gonna try to live in a real city.” I was scared of real cities. I always wanted to live in college towns like Urbana. So I thought I’ll just try living in this horrible big city, and of course I took to the city like a duck to water and realized I always should have – I’m very well suited to cities.

So while we’re on the subject of how you became a cartoonist, I wanted to ask you about comments I’ve heard more than once from women who are interested in comics that they feel like cartooning is not an available profession for a woman, that they thought it was very hard to be a woman cartoonist. Did you have any particularly gendered experiences?

Cartooning is not a fucking profession. I certainly did have gendered experiences, but I do want to just say that this whole approach to cartooning and art like it’s a profession, as though it’s people with jobs, and “they’re not recruiting women, the cartoon jobs aren’t recruiting women at the job fair.” It doesn’t work like that. But yes, I had extremely gendered experiences in my youth. And I am happy to say that the last time I went to a comics event which was the Alternative Press Expo here in New York (put on by the Museum of Cartoon and Comic Art), there are so many more women doing alt comics. It was not like that at all in the early ‘90s. It was horrible in alternative comics, just horrid.

It’s not just that I was female: I had a lot of other “social handicaps.” Being a woman was a social handicap. I was so bitter, so fucking angry. And, for good reason, being angry did not help my career, and in fact, I did the right thing, which was just to get out of it, stop pounding on that particular door.

Is the reason you left comics tied to this frustrating set of experiences?

Well, I got into newspaper comics. Newspapers were much more friendly to me than alternative comics. It was a cultural thing. Alternative comics were newer, smaller, very male dominated, and for whatever reason, things happened because of socializing. Now, I’m pretty sure that with my other social handicaps – my other social handicaps are that I don’t drink, I don’t take drugs, I don’t smoke, I don’t like bars. They were all really into all of those things, so people would go to parties and drink and that’s where everything happened. So it wasn’t just that I was a woman. However, I am certain that had I not been a woman, and had everything else about me been the same, I would have gotten much further. It was also this whole thing where — the alternatives grew out of the underground comics, and there were a lot of underground comics that were overtly misogynistic. And the few women cartoonists would say, “this is misogynistic; we don’t like this” and then the response to that, and this is strange, is that people would respond to that as though they were being censored, not criticized. So they were just not able to process that this would criticism. They would immediately get into this anti-censorship stuff. Maybe that’s related to stuff in Canada, because Canada was and still is censoring anything that could be considered porn, which includes a lot of comics. So the threat of censorship in Canada was very real.

I think that might be giving them too much credit.

I’m trying! But you know I wasn’t out to censor anybody – a, how could we and b, why would we want to. We were criticizing it and then suddenly we were accused of being a censor, and they were not into that. I did notice that the few women who were relatively successful underground cartoonists were either married or having sex with successful men cartoonists. So I did sort of go, hmm. Now, I’m not going to name any of them, but that was the case. And there would be depressed or even autistic male underground cartoonists and they would be fine. They didn’t have to go to the bars and do all this stuff. They didn’t have to sleep with the other cartoonists [laugh]. They didn’t have to be cute and bouncy; they were fine. But if you were a woman and you were like that, that was nowhere. And to be honest…I don’t know. I don’t really fucking know. I’m glad it’s over. I’m glad I got out of it, and I’m really glad that when I went last, there were lots of women there and these issues seemed to be just infinitely smaller now.

But it was still happening when you got out?

Oh yeah, it was a nightmare, still, when I stopped going to any comic conventions in the mid-1990s. I remember the last gig, I don’t remember what year my last Diego con was, but I was just like, I can’t ever do this again. [laugh] This is self-abuse. I guess it was shortly before I started doing Fluff. I reached a point where, “ok, I’m not going to do comics. Newspaper comics are different from comic book comics. They have nothing in common, and I am pursuing the newspapers.” That was probably 1995; I don’t remember when I started Fluff.

So I did this syndicated strip at the Universal Press – thank you Universal Press for the glorious opportunity, which I am eternally grateful for – but I did burn out. It just wasn’t fun at all anymore.

Was it the routine deadlines and the need for consistency?

Yes, the routine deadlines and the need for consistency, and also just the volume of it, every damn day. I guess that’s the consistency. The same format every single day, and so I only had this vague memory of when art was fun, and I was like “how did this happen; how did I get here?” I was just thinking I gotta have fun again.

Do you think it affected the quality of you work near the end of the strip, or was it just that it wasn’t meaningful to you at that point?

No, I’m competent. I’m always competent. By the end though, I couldn’t bear to write it, so thank god, I got my friend Ian Akin to write it, so you’ll see at the end the later Fluff’s say “Akin/Paley” or “Paley/Akin”; he did a really good job.

That makes sense though with the way you were saying: you built your chops as an artist so the drawing was always fine.

Yeah, I call that craft, now. I can do the craft, although I can’t do that stuff anymore. My soul just rebels. And obviously I couldn’t really keep doing it then ‘cause I quit. But the quality didn’t suffer. I remembered the joy I felt when I was 13 and making Super8 animation, and I had also just started dating “Dave” (Editor’s Note: Dave is the character name she uses for her ex-husband in Sita Sings the Blues), who was a professional animator, and he had an animation table, which I’d never used before.

I did Super8 animation when I was a kid in Central Illinois with no real support. There were no animators there. If there were any, they weren’t going to help a 13-year-old girl, so I had books, and that’s it. But I never had any equipment for it. An animation table is like a light box, and there’s paper with pegs, and he had this animation table, and I was “wow, I wanna do this again,” so I did. I also borrowed a friend’s Super8 camera and just picked up where I left off when I was 13 or 14 – and sure enough it was fun. My joke is that I found something that took more work and paid less than comics. That’s what I needed to have fun.

Did you work as an animator, or was this something you just did for love?

No, I wanted to keep it pure, the love of the craft. When I was quitting Fluff, I said “make art not money, make art not money. Remember that.” And of course I forget periodically and get confused and think that I should be making money and not art. They’re not mutually exclusive, not at all; but you’ve got to remember: don’t do stuff that’s bad for your soul in order to make money.

One of the things that people do leverage against copyleft is that you don’t get the quality you get with traditional methods.

You just get more of everything: you get more crap and more quality. I’m also really excited about more voices getting to be heard. What’s so different for me now is that my work can reach an audience, and it was so frustrating in the age of gatekeepers. I am so fucking sick of gatekeepers, who just defined everything that happened to my art for so long.

Out of completely cost benefit analysis motivations?

No, no, it was just their own taste. These are human beings, they are extremely fallible. A lot of them are really fucked up people, and they have these jobs where they’re supposed to make decisions about what their audience wants, and they’re frequently wrong. Even really smart really nice people in those jobs are frequently wrong. Those are not jobs anyone should have.

It should be collective.

Right, let people see it and let people decide whether they like something. I’m freeing all of my old strips under copyleft licenses [Editor’s note: many are already available on archive.org; hyperlinked names of comics in this article point to the archive.org page where you can download them.] And I would so love a publisher to publish a book of them, or some of them – anything they want. And the fact is any publisher could do that. But whomever does it first will have the competitive advantage. People tend to buy copies that are available and accessible rather than putting together their own. I have a volunteer effort to put all my old strips on WordPress blogs so that all of them are accessible. I have an enormous amount of this stuff. I was really hoping it would be up and running sooner than it has been because I’m trying to set an example and I’m trying to get my work seen again. I’ve got all these great old comics, and my work is obscure. All my newspaper strips are on archive.org. They’re apparently not accessible enough for them to be easily shareable; they’re still too difficult to find, even though they’re free. I want people to build on them.

The only publishers doing open-licensed works are tech publishers. Pop culture publishers – it is anathema to them. And the tech publishers don’t do pop culture. I actually asked O’Reilly, but physically a lot of work needs to be done. I’ve done the work of making the comics and I’ve done some work to make them accessible, and if a publisher could put it together, then people could see it online and say “is there a book of this?” And then buy that publisher’s books!

So you can have niche audiences, which scares people. It’s true when you have lots of niche audiences it’s a lot harder to control the masses, because if you just have limited information from just a few centralized points of distribution, it’s much easier to control everyone and we’re getting a situation where all kinds of niches can get the kind of culture that they want and people are saying things like, oh, and this means they’re not going to be exposed to things that they don’t like and that’s terrible, and look, these people with politics that we abhor are forming their own little communities and saying these things that we don’t like to each other, and yeah, I don’t like it either. I realize that there will be little communities of people that say terrible things that I would never want to hear, and I don’t have to. But there’s so much fantastic art that never would have made it through a gatekeeper system.

The more gatekeeping there is, the more culture is funneled. It just gets funneled more and more and more. I understand the point that not having gatekeepers means you get a lot of niche audiences, but it seems like if you don’t have niche audiences you have niche culture.

Yes! One culture fits all – but it sure didn’t fit me, and mine didn’t fit it. Didn’t fit that niche, and so the gatekeepers were like, “No. I don’t think this is the lowest common denominator and we’re only looking for the lowest common denominator.” And mine wasn’t that. So if it’s out there, the right audience finds my stuff, and there’s plenty of people that appreciate my stuff.