After reading that MFA students writing fantasy and science fiction still feel ostracized in their graduate programs, Stuart Jaffe declared in a blog headline last year: “Thought We’d Escaped the Genre Ghetto.” I agree with the sentiment (and also teach an undergraduate creative writing class that includes fantasy and SF), but the metaphor troubles me.

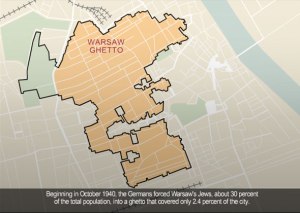

When I see the word “ghetto,” I picture the 1978 NBC mini-series Holocaust. I haven’t watched it since I was twelve, but I remember the Warsaw Ghetto sets, that neighborhood of some 400,000 Jews rounded-up and walled-in by Nazi Germany. I don’t know if Auschwitz technically counts as a ghetto, but that’s where most of the population ends up.

Not all ghettos are quite so dire. Manhattan’s Lower East Side or Chicago’s South Side are racially and economically segregated, but there are no ten-foot, barb-wire walls circling them. Still, “ghetto” is an odd term to apply to fiction writers. I don’t know when the trend started, but Thomas Pynchon, a front-runner in literary genre fiction, hinted at but didn’t quite commit to the term in his 1984 New York Times essay, “Is It O.K. To Be A Luddite?” 19th-century Gothic fiction, Pynchon lamented, “was judged not Serious enough and confined to its own part of town,” adding that the Gothic “is not the only neighborhood in the great City of Literature” to “get redlined under the label ‘escapist fare.'” Other hoods on Pynchon’s City map included Western, mystery, romance, and science fiction.

“Le Guin Blasts the ‘Genre’ Ghetto,” reported The Oregonian when fantasy and SF author Ursula Le Guin opened Portland’s Arts & Lectures series in 2000, focusing on the exclusion of genre writers by critics and academics: “She is not happy that the publishing world, centered in New York, often regards Western writers as only of regional interest. And she is especially unhappy that science fiction, fantasy, mystery and every other type of fiction except realistic literary fiction are consigned to ‘genre’ status.”

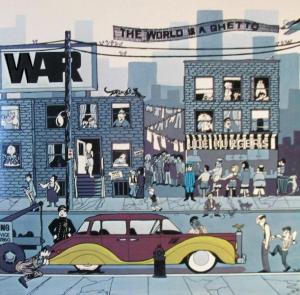

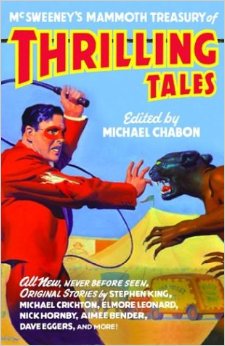

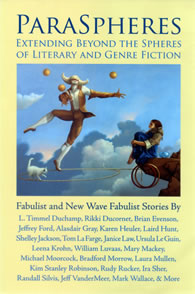

The journals Conjunctions and McSweeney’s challenged that literary districting in 2002 and 2003 when each devoted a genre-crossing issue to guest editors Peter Straub and Michael Chabon. Gary K. Wolfe, in his essay “Malebolge, Or the Ordinance of Genre” included in Conjunctions 39, repeated Pynchon’s and Le Guin’s complaint that “these fields had become ‘ghettoized,’ isolated from the literary mainstream,” noting that “Genre writers still complain of the ‘ghetto’ in which they see themselves forced to toil.” James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel, editors of the 2006 Feeling Very Strange: The Slipstream Anthology continued the metaphor: “Nobody calls mainstream writers ‘mainstream’ except for those of us in the ghetto of the fantastic.” Chabon longed to see all fiction shelved together: “For even the finest writer of horror or sf or detective fiction, the bookstore, to paraphrase the LA funk band War, is a ghetto.”

I’m not nearly as cool as Michael Chabon, so I had to google the lyrics to “The World is a Ghetto”:

Walkin’ down the street, smoggy-eyed

Looking at the sky, starry-eyed

Searchin’ for the place, weary-eyed

Crying in the night, teary-eyed

Don’t you know that it’s true

That for me and for you

The world is a ghetto

Wonder when I’ll find paradise

Somewhere there’s a home sweet and nice

Wonder if I’ll find happiness

Never give it up now I guess

Don’t you know that it’s true

That for me and for you

The world is a ghetto

That’s from 1972—though even I know the band’s later hits “Why Can’t We Be Friends?” and the ubiquitous “Low Rider.” War was a genre-crosser too, drawing from the neighborhoods of funk, R&B, rock, reggae, Latin, jazz, and reggae with a line-up of musicians hailing from a range of more literal hoods.

None of the band members, however, were from 17th-century Italy—where the word “ghetto” was born. It may be a reference to a foundry near Venice’s first Jewish ghetto, though “borghetto” (small borough) seems more likely to me. By the turn of the 20th century, the term could be applied to any minority population crowded into an urban quarter. By the turn of the 21st century, it could mean any subgroup of authors crowded onto a bookstore shelf.

Mary Elizabeth Williams’s “In and Out of the Genre Ghetto,” a review of seven lesbian novelists, addresses the benefits and dangers of categorization:

“The term “lesbian literature” is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it flags a genre, enabling a sometimes maddeningly invisible segment of the population to exchange stories about its own community – and when it seems that half the paperbacks in the world have Fabio on their covers, that can be a good thing. On the other hand, the phrase smacks of ghettoization, implying: “subculture!” “alternative!” “fringe!” and, worst of fail, “amateur!” You don’t read a book merely for a glimpse of satisfying self-recognition. Good writing speaks to something in everyone.”

Williams criticizes those authors of lesbian literature who “fail to communicate with the outside world and universalize their message.” The phrase “outside world” further echoes World War II (“The Nazis closed off the Warsaw Ghetto from the outside world in 1940”), but “universal” may be the bigger problem. I find it often on the backs of books written by African Americans. According to review blurbs excerpted for the paperback edition of James McBride’s The Color of Water, the memoir “resonates with universal themes of family, faith, and forgiveness.” In fact, it “goes beyond race” and even “transcends race and touches the spirit”—as apparently does Danzy Senna’s novel Caucasia, which “transcends race even while examining it.”“Everyone will be enriched by reading” Gregory Howard Williams’s Life on the Color Line because it gives “readers a greater understanding of humankind.”

I assume these promises of colorblind spirit and race-transcending universality are targeted at white readers, reassuring them it’s okay to read outside their neighborhoods, that they haven’t wandered into a bad part of town. After being inspected and approved by customs and Homeland Security officers, these book are safe for consumption in any zip code—even gated suburban communities. If the book is universal then it isn’t about a minority group, it’s about everyone, and so it’s about white people. It’s escaped the ghetto completely.

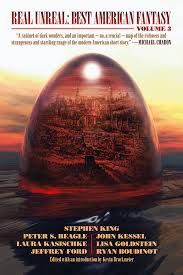

21-century genre writers have the same ambition. Lydia Millet of the Los Angeles Times recently praised Jeff Vandermeer “who after numerous works of genre fiction has suddenly transcended the genre with a compelling, elegant and existential story of far broader appeal.” But Andi Schechter wrote in the 2004 Library Journal essay “Out of the Genre Ghetto”: “Mystery’s adherents have always believed [mysteries novels] to be true novels in every sense of the word and bristle at the snobbery in the expression ‘transcends the genre.’ Still, the literary elite has long condemned crime fiction to obscurity in the genre ghetto.” The Magicians author Lev Grossman, writing for Time in 2012, bristles most loudly: “to say such books ‘transcend’ the genres they’re in is bollocks, of the most bollocky kind.”

Sometimes it’s the desire not to “transcend” that readers value. Gwendolyn Osborne in “The Legacy of Ghetto Pulp Fiction” documents the appeal of 1970s crime writers Donald Goines and Robert Beck —they’re “ghetto” in both senses—to middle class teens. By likening genres to “slums,” Chabon turns all mainstream readers into slumming tourists.

But even Chabon has trouble escaping the mixed metaphors of ghettoization. In “Ghetto Fabulist,” Financial Times reviewer Daniel Swift faults Chabon’s 2007 The Yiddish Policeman’s Union for not leaving its fantasy neighborhood. The hard-boiled detective novel is set in an alternate history in which the state of Israel is replaced by Sitka, a temporary Jewish ghetto in a district of Alaska, and so a world, writes Swift, that “can never be our world. Sitka can only ever be a fantasy place, a Narnia, which means also that [the novel’s hero] can never participate in the distinctive tragedy that marks” the heroes of Chabon’s works of narrative realism.

The New York Post oddly accused the novelist of anti-Semitism, though in a lecture I attended at Washington and Lee University in 2008, Chabon linked his exploration of genre fiction with his Jewish identity. Perhaps it’s that dual transcendence that appealed to The Nation’s William Deresiewicz: “The book is so good not despite taking place in an imaginary world but because of it.” So like Senna, McBride, and Williams, Chabon enriches mainstream readers by exploring life on the genre line.

Unpacking the ghetto metaphor also releases the whiff of miscegenation behind the rhetoric. In his review for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Cliff Froehlich calls Chabon’s novel “a beautiful marriage of high and low: a novel with a literary mind and a populist heart.” Substitute “high” with “WASP” and “low” with the ethnicity of your choice, and you’ll see why maybe ghetto isn’t such a great term to describe books.

The New Yorker‘s Joshua Rothman recently coined the term “genrefication” to describe the migration of “important novels” into genre. He’s punning on “gentrification,” which typically involves rich white people displacing poor black people. Erica Jong would like female residents to expand beyond their old neighborhood, but in order to enrich the rest of the city and without losing their identity. In her 2007 Publishers Weekly essay, “Ghetto (Not) Fabulous,” she laments “the chicklit ghetto” and longs “to see the talented new breed of American women writers . . . protest their ghettoization” and “celebrate our femaleness rather than fear it.” Such a celebration would not mean an escape from a gender ghetto to the universality of male readership but a remapping of the entire city.

I’m all for it. No more ghettos. This town needs a new metaphor.