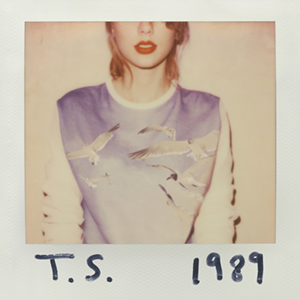

So why have you never heard of all these great bands? Two reasons: 1) you and that band run in different rabbit dens, and 2) Taylor Swift.

“If you chase two rabbits,” Swift told USAToday, “at some point you end up losing both.” By rabbits she means commercial markets, and for her maximizing revenues requires an allegiance to the larger bunny, pop, as her jilted country fans hop away. “I needed to pick a lane,” Swift said, criticizing her 2012 album, Red, because it featured “mandolin on one track, then a dubstep bass drop on the next song. You’re kind of thinking are these really on the same album?” So her new album, 1989, chases pop fans straight down the “80s synth-pop” lane. This, according to one of her collaborators, is evidence of Swift “relentlessly pushing herself to be unafraid of taking chances.”

Now I’m not seriously criticizing USAToday for its lack of cutting-edge journalism. The Taylor Swift article is an advertisement, and the soundbites are her corporate interests talking. Mixing mandolin and dubstep was taking a chance, the dubstep half of the album yielded Swift’s first No. 1 single, and so now she is “unafraid” to solidify that pop base. Even the year 1989 signals risk aversion. By the late the 80s, the pleasant chaos of the New Wave upheaval had been absorbed into predictable pop formulas. Devo and the Talking Heads had devolved into the Bangles and Tear for Fears.

Swift’s one-rabbit approach also runs counter to some of the best mandolin-dubstep fiction of the 80s. Margaret Atwood, then an acclaimed novelist of the purely narrative realism mode, published her first speculative novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, in 1985. Toni Morrison won the 1988 Pulitzer for chasing those same two rabbits, speculative and realism, with Beloved, a literary horror novel. And Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen put comic books on the literary map for the first time in the 80s too. Superheroes, ghosts, dystopic futures–you’re kind of thinking are these really in the same genre?

Jon Caramanica in his New York Times rave of Swift’s new album provides one of the best working definitions of genre I’ve seen in a while: “It’s a box, and a porous one, but a box all the same.” Caramanica also calls calls 21st century pop “overtly hybrid” and country a “hospitable host body,” one that the body-snatching alien Swift has sucked dry and discarded. That’s a lot of genre metaphors to juggle at once, so I’m going to stick with cars and rodents for now. Despite Swift’s relentless push down the pop lane, the 21st century literary highway has seen some major additions to the two-rabbit playlist. My course, 21st Century North American Fiction (I know, not as catchy as any of Swift’s titles) features a list of authors straddling “literary” (meaning “artful,” not “set in the real world”) and “genre” (any of those formerly lowbrow pulp categories of scifi, fantasy, horror, mystery, romance, etc.).

At first it sounds like a marketing wet dream: combine two genres and double your audience. You like zombies? You like literary fiction? We’ll you’re going to love Colson Whitehead’s literary zombie novel, Zone One! But instead of bringing two diverse readerships together, a two-rabbit novel often appeals only to that sliver-thin, Venn diagram cross-section of readers willing to straddle both categories. Instead of expanding your audience, the mandolin-dubstep approach can decimate it.

Before assigning Zone One to my students, I tried to get my book club to read it, but one of our group’s economics professors (we have two) despised it. In addition to his expertise in business, Professor MacDermott is a zombie aficionado (which has also resulted in our forming a Zombie Club splinter group). I asked him to write up his critique of Whitehead for my class:

“While it may have some literary merits, I don’t read zombie books for literary anything. Contrary to just about everyone’s opinion, the book did not strike me as terribly well written (unless well written = slog). I saw one review that said the “language zings and soars.” Criminy – that’s heavy handed. Perhaps I am a bit of a grunt when it comes to ‘good writing’ but I didn’t see it. The biggest knock against it in my mind is that very little happens and what does happen is all over the place. Most of the zombie / dystopian books I have read (and that is a shamefully large number) are stuffed with action … probably too much. This one had very little. . . . So, I guess in the end my recommendation would be to not read this book because while some may find the writing compelling, there is not much of a story (yeah … blah blah blah social commentary … blah blah blah). I took a look at the reviews in Amazon and found I agreed with several of the 1-star reviews (those written by the troglodytes).”

In the end, he likened it to handing The Iliad to someone because they said they liked war books. “That,” he said, “is what it is like to hand Zone One to a zombie-phile.”

So much for droves of zombie fans flocking to Whitehead. And many literary readers are equally repulsed. Shenandoah recently published a Noir issue, opening the door to a blog discussion of the relative merits of genre and literary fiction and their hybrid love children. Editor R. T. Smith drew a line in the literary sand:

“Hard-boiled, thriller, mystery, crime – following the spoor of these labels will draw an investigator into the territory where I think noir simmers. It’s a somewhat different direction from super powers, paranormal events, zombies, weredogs, closet monsters, witches, alien storm troopers, time travelers. These are terms more likely to lead away from my noir zone, where characters who metamorphose don’t grow fangs, fly away, deflect bullets or sport tails with stingers. The gumshoe’s revolver may somehow fire eight rounds without being re-loaded, but it doesn’t spew bats or emulsify anyone. Neither physics nor metaphysics are problematized, though the emphasis may be on aesthetics and ethics. It’s an old personal preference – naturalism over supernaturalism, physics and metaphysics over hocus-pocus and the “black box” – a question of conventions and confidence.”

Poet and historical-mystery author Sarah Kennedy articulated the anti-zombie stance too:

“For me, the problem with a great deal of literature about monsters and other non-human characters is that they become formulaic or silly in their attempts to prove that they’re doing something “serious” when in fact they’re just retailing the old conventions. Zombies are horrible looking and they eat human flesh. Even if a writer gives a zombie a science-fiction virus or (ick) a heart of gold, the character is still going to have all the signs of the formula: scary, grisly-looking, flesh-eating. It’s probably going to walk a bit oddly (what with those bits and pieces falling off). It’s going to be hard ever to convince me to take that seriously.”

And this includes Whitehead’s cross-bred literary zombies: “I have tried Zone One but frankly found it both pretentious and tedious and couldn’t finish. There is no story there, at least not one that engaged me.”

Kennedy’s and MacDermott’s definitions of “story” may be opposites, but neither was satisfied by Whitehead’s mandolin and/or dubstep skills. Trying to satisfy both can mean satisfying neither. And it’s not just literary zombies getting run down by one-lane readers.

My class is also studying Karen Joy Fowler’s The Jane Austen Book Club, a literary novel that rode the “chicklit” wave up the best-seller charts in 2004. Despite Fowler’s winning the 2014 PEN/Faulkner (an award controversially denied Morrison’s Beloved), her novel still carries a non-literary taint. My department’s Austen expert hasn’t read it and looked at me suspiciously when I suggested she might. Another colleague, Professor Pickett, observed one of my classes for my tenure review and wrote in her evaluation afterwards:

“I had specifically asked Chris if I could observe a class devoted to this particular novel, both because I had started reading it myself over the summer and also because (as a result) I was curious about how he would handle the challenge of teaching a book I would unthinkingly have assigned to my own idiosyncratic genre of “airport bookstore” novel–one “light” enough to read in a distracting environment but “respectable” enough not to be embarrassed if caught reading–basically trade paperbacks for the 30-something female.”

Even my students are wary of the novel. One, Libby Hayhurst, wrote in a homework response:

“this is by far the most entertaining book we’ve read, which makes me instantly mistrustful. While literary fiction can entertain, this is surely not its point. I have found myself reading this book only enjoying the plot and the characters, and without the desire to even take a stab at the deeper meaning . . . I am not sure the Jane Austen Book Club falls under ‘literary fiction’ (although I AM hesitating, but is this just because I’m reading it in an English course?).”

This despite Michael Chabon opening the course with his appeal:

“Entertainment has a bad name. People learn to mistrust it and even revile it. . . . Yet entertainment—as I define it, pleasure and all—remains the only sure means we have of bridging, or at least of feeling as if we have bridged, the gulf of consciousness that separates each of from everybody else. The best response to those who would cheapen and exploit it is not to disparage or repudiate but to reclaim entertainment as a job fit for artists and for audiences, a two-way exchange of attention, experience, and the universal hunger for connection.”

Personally I don’t find Taylor Swift entertaining, but I am entertained by plenty of popular and non-popular music. I don’t have a problem with Swift, just her claim to chance-taking and her repudiation of albums that appeal to more than one kind of rodent. Mandolin-strumming and dubstep-dancing rabbits are more than roadkill on opposing lanes of entertainment traffic. I hope 1989 isn’t our only future.