Ed note: This post was put together with the help and collaboration of Alex Buchet.

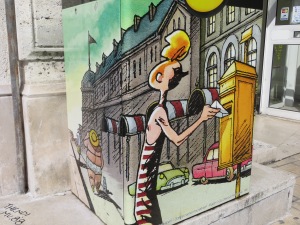

I met fellow superhero scholar Alex Buchet for the first time in Paris during a World Cup game televised in an Irish pub before my wife’s poetry reading in the building’s medieval cellar. After bemoaning the sorry state of Hollywood superheroes, Alex and I agreed we should collaborate on a project. I was headed to Angouleme, France’s center for comic book research, where I would be delicately flipping sixty-five-year-old newspaper sheets printed with the still-bold colors of one of France’s first superheroes, Atomas.

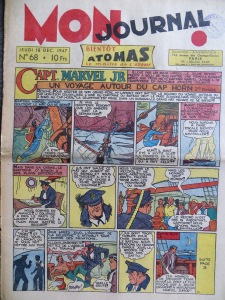

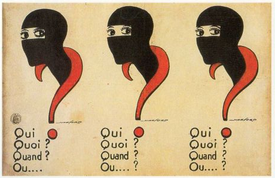

Mon Journal (“My Journal”) ran its first weekly issue on August 8, 1946. It’s front and back cover adventure strips were in color, with four of the six, inner pages in black and white, a standard format among French, newspaper-style, comic strip periodicals of the time. Beginning with No. 21 on January 23, 1947, reprints of the American “Captain Marvel Junior” appeared on the cover. Mon Journal also translated an American magician strip, retitled “Ibis L’invincible,” for one of its two interior color pages. “Captain Marvel Junior” continued on the cover until December 18, 1947, after which the series moved to its own inside, black and white page.

No. 68 also announced a forthcoming feature: “Soon Atomas the Master of the Atom.”

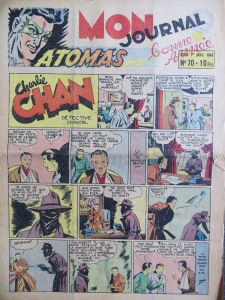

No. 70 featured Atomas in its revised header and “Charlie Chan” as its new front feature:

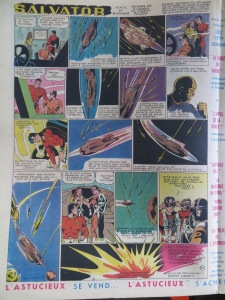

“Atomas” replaced “Hopalong Cassidy” on the back cover. Each full-page episode included the credits: “par Pellos ed R. Charroux,” but the strip’s origins are more complex. According to coolfrenchcomics.com, writer Robert Charroux created the character for artist Auguste Liquois, who was drawing a similar superhero space opera “Salvator” for the weekly Tarzan periodical in 1947:

Liquois drew Charroux’s first “Atomas” page:

The page may have appeared in Mon Journal No. 69, but the issue is missing from the Angouleme collection. If so, it would have appeared in one of the four black and white, interior pages. When Pellos (AKA Rene Pellarin) took over the strip, he used the same opening script for Mon Journal No. 70:

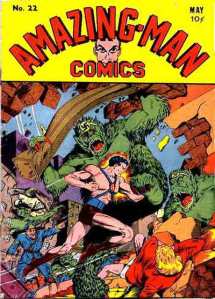

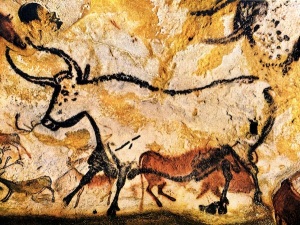

The two versions highlight a range of differences in artistic approach, including Pellos’ asymmetrical panel layout and Liquois’ comparatively realistic figural style. I prefer Pellos, though his Atomas may also owe a debt to Bill Everett’s scantily-dressed and A-chested Amazing-Man:

Centaur Publications ran Amazing-Man from September 1939 to February 1942, five years before Pellos started illustrating Chirroux’s script. The series had also appeared in France, though Amazing-Man was renamed “Surhomme” or Superman:

The Pellos version of Atomas continued until Mon Journal No. 85. The Angouleme collection does not include No. 86 (or any subsequent issues), but according to coolfrenchcomics.com, the final issue was drawn by an uncredited artist who produced it in the style of Pellos, “d’apres Pellos.” Mon Journal then replaced the series with “Zorro.”

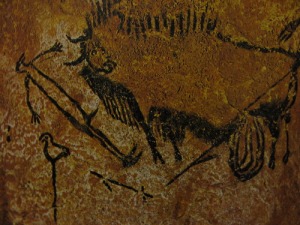

I was studying “Atomas” to test the claim that the violence of American superhero comics influenced their French counterparts. In short, Atomas is less violent than his immediate Mon Journal predecessor, Captain Marvel Junior. Though he often wrestles and flips his opponents, Atomas throws only one punch in his sixteen pages:

That maniacal smile is a bit troubling though, and unlike Captain Marvel Junior and the majority of American superheroes of the late 40s, Atomas uses deadly force, which Pellos depicts overtly:

Pellos adds a category of representation I’d overlooked in my initial lexicon of violence, merging an impact burst with a panel frame:

Chirroux also scripts a surprising range of wide-scale death, from the tidal wave destruction of the moon crashing into the ocean to a heavily populated city exploding, images uncommon in American comics. Pellos’ exploding city holds even greater meaning less than three years after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In contrast, when Wayne Boring depicted the destruction of a Kryptonian city in 1944, he included no figures in the foreground, reducing the human impact of the violence. France’s comics tabloid L’Astucieux reprinted Wayne’s art in May 1947, less than a year before “Atomas” premiered:

The post-war context highlights one other significant difference between Pellos and Liquois. I’ll let Jean-Pierre Mercier, conseiller scientifique at Angouleme’s le Musée de la Bande Dessinée (comic book museum), explain:

“Why was [Liquois] so abruptly discharged? Maybe because publishers had discovered that, during WWII, he published in Le Téméraire, a collaborationist, anti-English, anti-Russia, anti-American and very anti-Semitic weekly magazine for kids. Even worse, Liquois published a very harsh story on the French Resistance in a satirical magazine named “Le Mérinos”, and it caused him a lot of trouble after the war. This is precisely what happened to him at “Vaillant”. He got fired right after the publishers discovered the Merinos story. Is it possible that he got the same reaction at Mon Journal (Mme Ratier, the woman publisher of Mon Journal was part of the Resistance during the war). And Liquois’ name disappears in Vaillant summaries in 1947… We know Mon Journal stopped because the publishing company had money problems, and that’s the main reason why they merged the two titles in only one, and therefore had to stop several series on a very short period of time, including Atomas.”

There is currently little or no scholarship in “Atomas” because the series has never been collected or translated. Until now. Alex Buchet’s English version is now online.