Google “jennifer egan” and seconds later the term “metafiction” will attach itself leech-like to the side of her postmodern head.

I know this because members of my university have made the possibly foolhardy decision to ask me to give a talk on the Pulitzer winning author for our 2013 Tom Wolfe Weekend Seminar. I’m to place A Visit from the Goon Squad into “the context of contemporary American culture” with “a discussion of Egan’s special skills as a writer,” keeping in mind she will be “sitting right there in front of you.”

I regularly tell my first year comp students that even if we could materialize authors in our classroom (usually during a discussion of Henry James’ mind-blowingly ambiguous The Turn of the Screw), their opinions would be completely irrelevant. Readers and only readers determine the meaning of a text. Except of course in this case. Because that will be the actual Jennifer Egan. In the front row. Listening. To me. Blathering. About her book.

Poetic comeuppance aside, the author’s physical presence will be especially apt for a discussion of Goon Squad. Chapter one opens: “It began the usual way . . .” and before you’ve waded in a dozen pages you’re knee deep in self-referential story-telling, overt comments about symbols and plot arcs and collaborative writing. Ms. Egan is pulling off her metaphorical mask and yelling: Look at me!

So now, after stretching to pluck David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction from my office book shelf, let me flip to Chapter 46: “Metafiction is fiction about fiction: novel and stories that call attention to their fictional status and their own compositional procedures.”

Apart from a requisite nod to the 18th century’s Tristram Shandy, Lodge spends most of his time chatting with John Barth and Kurt Vonnegut. William Gass coined the term in 1970, after Barth demonstrated the style in his 1968 novel Lost in the Funhouse. Slaughterhouse Five was published a year later. Add Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) and a couple of short stories by Robert Cover, and there’s your course syllabus for “Goon Squad: Founding Fathers of American Metafiction.”

Except, wait, here’s that inevitable moment, my weekly plot twist, where I veer to where I must always veer:

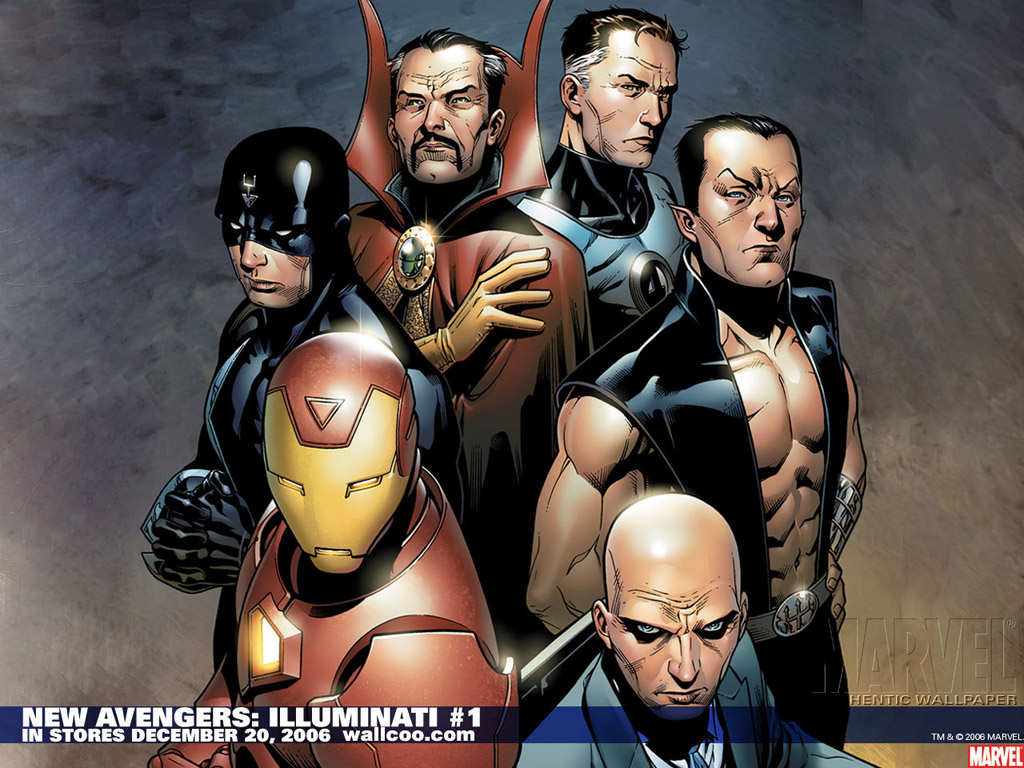

Superheroes!

No, no, no, NO. American metafiction did NOT begin in the late 60s. It was not a highbrow literary phenomenon. It was the lowest of the lowbrows, the pulpiest of the pulps, that ultimate literary stepchild, the comic book.

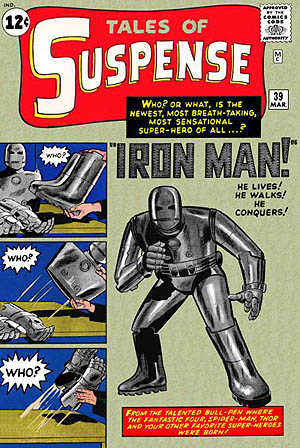

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby beat Pynchon by a half-decade. In Fantastic Four #2, on newsstands in 1961, Reed Richards convinces an alien race not to invade Earth by showing them drawing of monsters. “Those are some of Earth’s most powerful warriors!” he tells them, while thinking, “I pray he doesn’t suspect that they’re actually clipped from ‘Strange Tales’ and ‘Journey into Mystery!’” Two other Marvel titles sharing newsstand space with Fantastic Four.

Two issues later, the Human Torch chances onto a stash of old comics. “Say! Look at this old, beat-up comic mag! It’s from the 1940’s!!” It features the Golden Age Namor on the cover. “The Sub-Mariner! . . . He used to be the world’s most unusual character!” And guess who shows up two panels later?

In issue five, Johnny’s reading habits have expanded. Reed asks, “What are you reading, Johnny?”It’s The Incredible Hulk #1, out the same month. “A great new comic mag, Reed. Say! You know something—! I’ll be doggoned if this monster doesn’t remind me of The Thing!” Because he’s supposed to. Marvel created Hulk because of the Thing’s popularity.

The cover of FF #9 asks: “What happens to comic magazine heroes when they can’t pay their bills and have no place to turn?” But #10 is even bolder: “In this epic issue surprise follows surprise as you actually meet Lee and Kirby in the story!!” The authors stare up at the action from the front row.

Stan: “How’s this for a twist, Jack? We’ve got Doctor Doom as one of the Fantastic Four!!”

Jack: “And Mister Fantastic himself is the villain!! Our fans oughtta flip over this yarn!!”

As promised, Dr. Doom uses the Marvel duo to lure Reed into a trap.

Johnny: “Phone call for you, Reed! It’s Lee and Kirby! They’d like you to go to their studio to work out a plot with ‘em!”

Reed: “Strange…we just finished discussing a new plot yesterday!”

Thing: “Tell ‘em if they don’t stop makin’ me even uglier than I am, I’m liable to go up there and wrap this two-ton weight around their skinny necks!”

Issue 11 goes further still. The team has to stand in line to get a copy of their own comic book, and then they go home to answer fan letters, shattering the last remains of the fourth wall. Mr. Lumpkin, their mailman, laments in the final panel: “Blankety blank fans and comic magazine heroes, and letters to the editor pages! Ohhh my achin’ back!”

The trend dies a quiet death in the next issue when the Hulk shows up with no mention of that comic mag John had been reading. Marvel traded in metafiction for multi-title continuity. That brings us into 1962, still eight years before Barth coins the term.

And does all of this put Jennifer Egan into “the context of contemporary American culture”?

Um, no, not really.

So you’ll forgive me if I sign off now and finish reading Goon Squad.

‘Nuff said.