“A lot of times your neighborhood, your town, your city is being invaded by people who you think are going to hurt your family, your society,” he says. “Well, then you have to act, because the government isn’t going to come help you.”

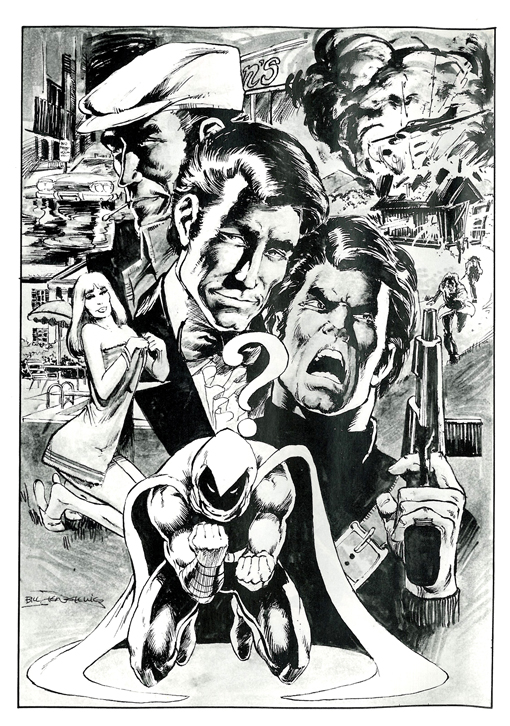

And there’s the premise of almost every superhero story ever written. Only the speaker isn’t from a comic book. He’s from Iguala, Mexico. Reporter E. Eduardo Castillo interviewed him for the Associated Press late last year (the article is here). “He would appear on camera wearing a ski mask,” explains Castillo, “and his voice would be distorted.” I can’t help but hear Stephen Amell’s distorted voice on Arrow. The set-up also reminds me of the Tom Bissell short story “My Interview with the Avenger” that appeared in the superhero issue of VQR a few years back (that’s Gary Panter’s drawing from the issue above).

Instead of a utility belt, Castillo’s interviewee “wears a bag with a strap over his chest in which he carries several walkie-talkies and cell phones, one of which he used to take calls and issue orders.” Instead of superpowers, “he usually carries a .38-caliber pistol and an AK-47 assault rifle.” He’s a killer—a trait that might put him in the same league as the Punisher or Steve Ditko’s The Question.

Here are more excerpts from Castillo’s article:

In recent years, residents of a number of towns and cities have taken up arms to protect themselves against drug cartels. “I can’t say I’m a vigilante,” says the killer, “but I am part of a group that protects people, an autonomous group of people who protect their town, their people.”

He says no one forced him to join his organization. His parents and siblings don’t know what he does. He raises cattle for a living. He isn’t married and has no children. Although he would like to have a family, he knows his future is uncertain. “I don’t really see anything,” he said. “I don’t think you can make plans for the future, because you don’t know what will happen tomorrow.”

“It’s not a pretty life,” he says. Life in an area torn by drug disputes is rarely pretty.

The killer has a grade-school education. He wanted to continue studying, but when he was a child there was no middle school in his town. “I would have liked to learn languages … to travel to other places or other countries. I would have liked that,” he said.

He acknowledges that what he does is illegal. He recognizes he would be punished if caught by the authorities. “For them, these (killings) are not justifiable under the laws we have, but my conscience – how can I put this – this is something that I can justify, because I am defending my family.”

He sometimes feels sorry about the work he does but has no regrets, he says, because he is providing a kind of public service, defending his community from outsiders.

If you take a standard definition of a superhero—I like Pete Coogan’s—Castillo’s interviewee seems to hit the mark. He uses his specialized skills to conduct a selfless, pro-social mission. Plus Castillo, like his reporter counterparts in so many comic book tales, provides his interviewee with a codename: The Killer. Though even with the mask, his “jeans and a camouflage T-shirt” aren’t your standard superhero costume, but he does wear a mission-defining iconic symbol on his forehead, the preferred placement before Joe Shuster drew an “S” on Superman’s chest. Castillo writes:

He wore a baseball cap with a badge bearing the face of Sinaloa cartel boss Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman and “prisoner 3578” – Guzman’s inmate number before he escaped through a tunnel from Mexico’s maximum-security prison in July, cementing his image as a folk hero.

Robin Hood was an outlaw folk hero too, but here things get a lot more complicated. Castillo’s killer works for a drug cartel.

Federal authorities told the AP that several drug gangs in Guerrero, including those that operate on the Costa Grande, act as self-defense groups to generate support from local residents.

“Of all the bad lot,” the killer said, Guzman “seems to be the least bad.”

In several cases, authorities have claimed these vigilantes are allied with rival gangs, and pass themselves off as self-defense groups to gain greater legitimacy.

He says he is defending his people against the violence of other cartels. Things would be much worse if rivals took over.

A rival gang, “would do worse damage.”

Superheroes tend to be more idealistic than that, but if the killer is looking at the big picture—like Ozymandias in Watchmen—is he still one of the pragmatic good guys? Since “violence spikes when cartels are fighting each other for control of territory,” is he making his community safer the only way he can?

Unfortunately, that way makes him “a man who kidnaps, tortures and kills for a drug cartel.”

The killer says he ‘disappeared’ a man for the first time at age 20. Nine years later, he says, he has eliminated 30 people – maybe three in error.

There are many reasons people are disappeared, the killer says. It may be for belonging to a rival gang, or for giving information to one. If a person is considered a security risk for any reason, he may be disappeared. Some are kidnapped for ransom, though he says he does not do this.

In fact, he maintains his own sense of morality in a variety of ways.

Some in his circumstances use drugs, but he says he doesn’t. “When people are on drugs, they’re not really themselves,” he says. “They lose control, their judgment.”

Unlike others, he says, he has standards: He doesn’t kill women or children. He doesn’t make his victims dig their own graves.

He doesn’t consider himself a drug trafficker or a professional killer, although he is paid for disappearing people. He does not see himself as bad.

He sometimes feels sorry about the work he does but has no regrets.

The problem is that people under torture sometimes admit to things that are not true: “They do it in hope that you will stop hurting them. They think it’s a way to get out of the situation.”

That may have happened to him three times, he says, leading him to kill the wrong men.

While Castillo’s interviewee provides a grotesque study in rationalization and self-deception, I’m equally disturbed by how well his tale parallels the tropes of superheroism and what those parallels suggest about the popularity of a genre about violent men who break the law while serving what they call the greater good.

(AP Photo/Dario Lopez-Mills)