I used to be a lone voice in the pop culture wilderness crying that Frankenstein should be refitted with a cape, tights, and an “F” on his chest. More oddly, I think the wardrobe change would fit equally to the doctor, Victor Frankenstein, as his creation, the Frankenstein monster. But I’m no longer so lonely in my wailings. Opening November 25, Victor Frankenstein makes the case for me.

Personally, I would have called the prequel Igor—since that’s its hook. Former Harry Potter super-wizard Daniel Radcliffe plays the mad scientist’s hunchback lab assistant. You may or may not agree that Harry is himself a superhero (muggle by day, transformed by accident, etc.), but James McAvoy is a no-brainer: the titular Doctor shares bodies with the X-Men’s super-brained Professor Xavier. The young version. McAvoy retains his pre-Patrick Stewart scalp.

Attached to those superhero creds, director Paul McGuigan makes his leap to the big screen in a single bound from the BBC’s Sherlock. For his new dynamic duo, Igor plays Dr. Watson to Victor’s Holmes. Plus actress Jessica Brown Findlay had the power of mind-control on the British superhero show Misfits. If that’s not already a complete body of superhero parts, screenwriter Max Landis cut his teeth on 2012’s Chronicle and the 2011 comic short The Death and Return of Superman.

But how are Superman and (either) Frankenstein related?

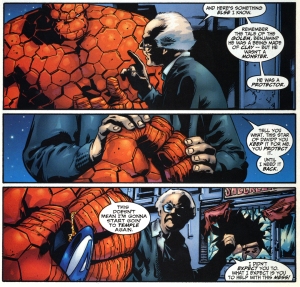

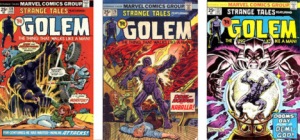

Well, the creature did play a gig as a Marvel superhero in the 70s. He teamed-up with Spider-Man, Iron Man and She-Hulk—though the supervillain Kang the Conqueror used him as a mind-controlled minion too (perhaps both McAvoy and Findlay could help him with that?). But Frankenstein and Superman were stitched together before comics even existed. In the 1919 film serial The Master Mystery, Harry Houdini battles Q the Automaton, a robot described as a “Frankenstein” that “possesses a human brain which has been transplanted into it and made to guide it” as a “conscienceless inhuman superman.”

That man of steel wasn’t the Man of Steel, but a pop cultural version of Nietzsche’s ubermensch. The German philosopher prophesied in 1883 that a breed of superhumans would evolve and take the world away from Homo sapiens. Mary Shelley was decades ahead of him. The author of Frankenstein wrote in 1818 that “a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth, who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.” That’s why Victor refuses to make a mate for his monster and why his monster declares himself his and humanity’s “arch-enemy.”

It’s the original Professor X vs. Magneto match-up. Or Superman vs. Lex Luthor, since Victor is also the original mad scientist, a character type so pervasive in comics it’s hard to keep track of them all. Like Victor, they’re usually a good guy who accidentally creates a monster—though, unlike Victor, the monster tends to be themselves.

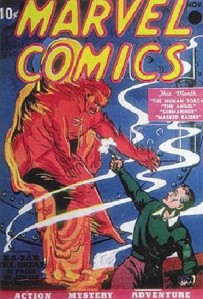

The Dr. Jekyll/Frankenstein merger culminated with Reed Richards when he transformed himself and his pals into the Fantastic Four. The Thing was so popular, Marvel created the Hulk next—fulfilling the Shelley/Nietzsche prophesy of an expanding race of monstrous supermen. When Bruce Banner turned into the Hulk for the first, artist Jack Kirby drew a Boris Karloff knock-off with a flat head and grey skin (Marvel flipped to a green complexion the next issue because the ink looked better).

Karloff’s stitched corpse was never part of Shelley’s plan though. Her Victor doesn’t even know how to reanimate flesh: “I might in process of time (although I now found it impossible) renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption.” His creature wasn’t human-sized either: “As the minuteness of the parts formed a great hindrance to my speed, I resolved . . . to make the being of a gigantic stature, that is to say, about eight feet in height.”

Early stage productions even draped him in a Greek toga—the first of a new god-like species. His “limbs were in proportion” (a big turn-on for early nineteenth-century readers) and the doctor “had selected his features as beautiful.” Sure, his skin was transparent yellow and his face a fit of twitching muscles, and next he’s serial murdering his creator’s loved ones—but, hey, when has a mad scientist’s scheme ever worked out exactly as planned?

Look at the twitching pile of recent superhero movies that include some nut job trying to take over the planet with a new species of devilishly superior uber-monsters:

- Ian McKellen’s Magneto planned his mutant conquest, complaining that “nature is too slow” in the firstX-Men.

- Michael Fassbender’s Magneto was still complaining in X-Men: First Class, but under the tutelage of Kevin Bacon: “We are the future of the human race. You and me, son. This world could be ours.”

- A month later in the first Captain American film, Hugo Weaving’s Red Skull gave Cap the same lesson: “You pretend to be a simple soldier, but in reality you are just afraid to admit that we have left humanity behind. Unlike you, I embrace it proudly. You could have the power of the gods!”

- Weaving’s Agent Smith had already explained to The Matrix fans: “As soon as we started thinking for you, it really became our civilization. Which is of course what this is all about. Evolution. . . . The future is our world.”

- Iron Man 3’s supergenius Aldrich Killian wanted to turn himself and his minions into the “new iteration of human evolution.”

- Just like Dr. Connors, aka the Lizard, planned to “enhance humanity on an evolutionary scale” and “create a world without weakness.” “This is no longer about curing ills,” he said in The Amazing Spider-Man. “This is about finding perfection.” Unfortunately, “Human beings are weak, pathetic, feeble-minded creatures. Why be human at all when we can be so much more? Faster, stronger, smarter!”

- And Dane DeHaan, reading from Max Landis’ Chronicle script, declared himself an “apex predator,” ready to wipe out humankind as Victor Frankenstein had feared his creature’s super-race would.

So who will save us from all these Frankenstein Supermen? Other Frankenstein Superman of course. Captain America, Spider-Man, Iron Man, even the X-Men’s radiation-saturated DNA, they all started as lab experiments. That’s the core of the Marvel superhero formula. Stitch a monster into tights and watch him save us from monsters just like him.

There’s a reason we confuse Victor and his creature. Superheroes are both kinds of Frankensteins.