A lot of media attention has been paid lately to the case of American football generally and the National Football League in particular. Recently, the NFL drafted its first openly gay man into its ranks, causing a great deal of celebration in some quarters and a high degree of consternation in others. As a fan of (American) football, I am interested in this story because of what it says about the social implications for individual players, team camaraderie, and the fans, too. I am thinking about this because I try to be mindful about and supportive of efforts to eliminate discrimination and promote equality regarding race and ethnicity; regarding sexual orientation; regarding gender; and regarding socioeconomic class.

Since I currently live in Sweden, I don’t see all the news (infotainment) about current events in the U.S., so what I have seen of the Michael Sam story I have found through websites that I visit on occasion. I saw stories on my BBC phone app; on Queerty.com and Advocate.com; and on other random links I saw on Facebook. What I did not see, though, in any instance, was editorial cartoons about this event, so I went hunting for them. Using a Google search, I found a few cartoons, some of which focused on Michael Sam’s race and others on his sexual orientation.

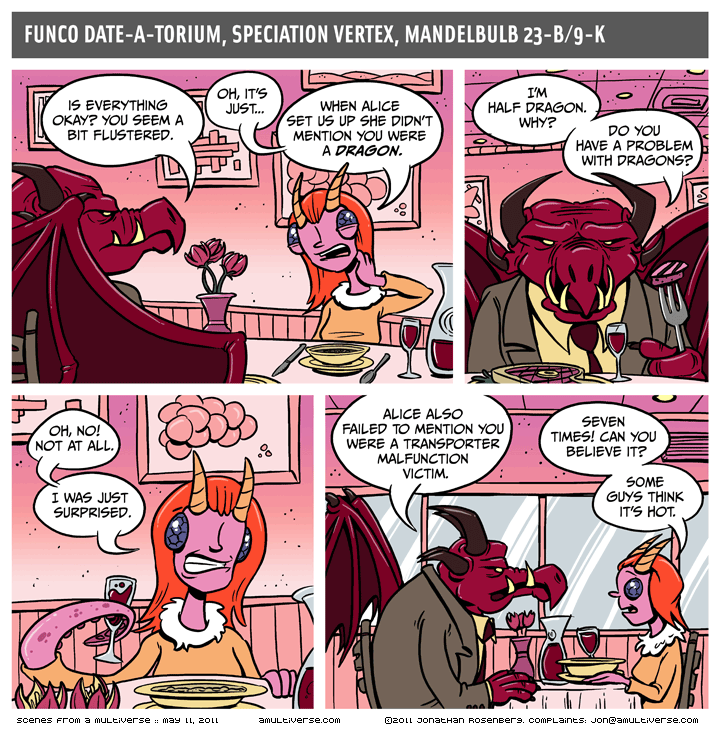

I include below some randomly chosen cartoons depicting some facet of the Michael Sam case. Does the cartoonist in each instance focus more on representations of race, more on representations of sexual orientation, or some combination of both?

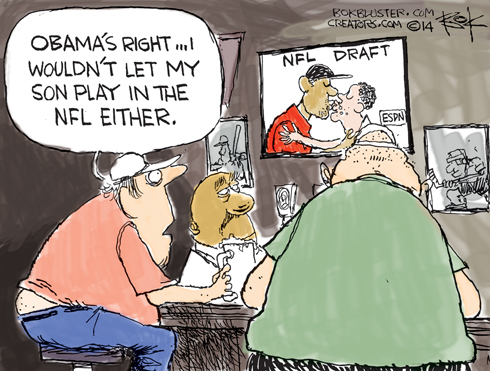

Bok (bokbluster.com/creators.com)

The first cartoon borrows President Obama’s earlier discourse regarding the NFL and the incidence of concussions and traumatic brain injury. Bok makes a connection between working class men, beer drinkers, and anti-gay prejudice. (Because of the perspective, we don’t see the butt crack, but we know it’s there and it is revealed.) The image on the television screen is of two men kissing. What is not clear is how the characters in the panel would react to the fact that it is apparently two men of different racial identities kissing. Since it is set in a ‘sports bar’ (pictures of hockey and baseball on the wall), readers might assume that it is a bold statement this man makes about not having a son play in the NFL.

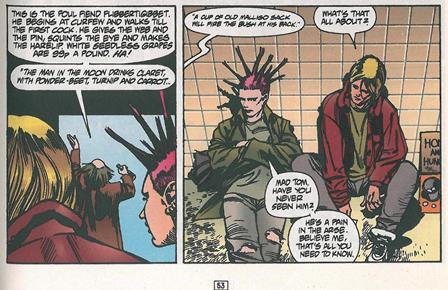

Drew Litton (http://www.drewlitton.com/)

This cartoon draws on the historical significance of racial integration in baseball (an interesting sports cross-over). Litton uses visual cues to communicate Michael Sam’s race, but he uses linguistic cues to communicate Sam’s sexual orientation (the newspaper in his hand). Robinson is pictured wearing his Dodgers uniform (the team he joined) but Sam is wearing his Missouri uniform (not yet having been drafted by the St. Louis Rams).

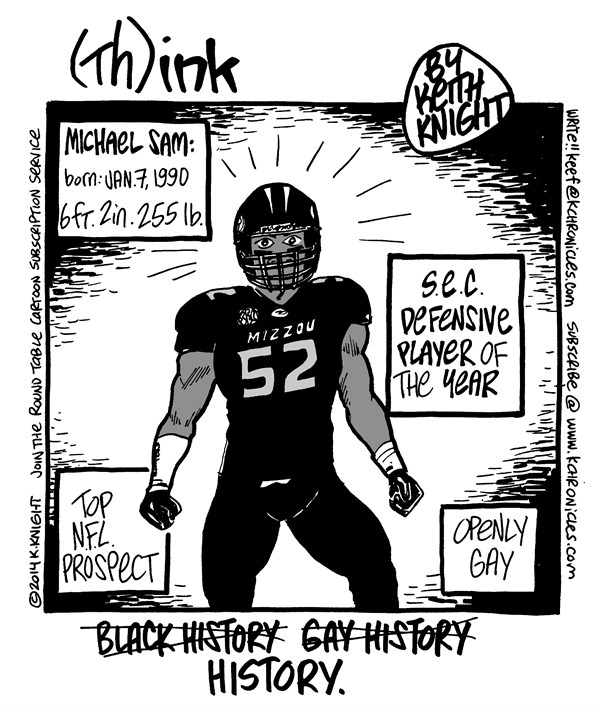

Keith Knight (www.cagle.com)

Knight’s technique relies much more on linguistic cues to communicate his thoughts about Michael Sam. It may be that Knight uses Sam’s stats rhetorically to establish the rationale for the caption, which shows the linguistic struggle over how to name the importance of this event. Knight decides that it is neither Black History nor Gay History but History.

In her 2009 article published in Visual Communication, Elisabeth El Refaie writes about visual literacies and the processes that readers use to understand political cartoons. Her essay is a pilot study exploring how readers make sense out of the visual and verbal elements in a panel. In her analysis, El Refaie explores five questions regarding the ‘multiliteracies’ required to understanding these cartoons: “How do readers: (a) establish the real-world referents of a cartoon; (b) impose a narrative on the cartoon image; (c) interpret the facial expressions of the depicted participants; (d) understanding text-image relations; and (e) establish metaphorical connections between the fictional scene of the cartoon and a political argument?” (p. 190).

What interests me about the range of cartoons shown above is how few of them rely on metaphorical representations to communicate their messages. Most of them are relatively literal scenes: representations of people having conversations about Michael Sam, or Michael Sam himself having a conversation about his future. Research on editorial and political cartoons discusses the tendency for artists to make their commentary using metaphor: combining two very different domains for the reader to interpret. (For more on cognitive metaphor in cartoons, see Bounegru & Forceville 2011; El Refaie 2003; among others.)

In my very limited search for cartoons about Michael Sam, I found just a very small number that relied on metaphor to communicate the meaning. Here is an example:

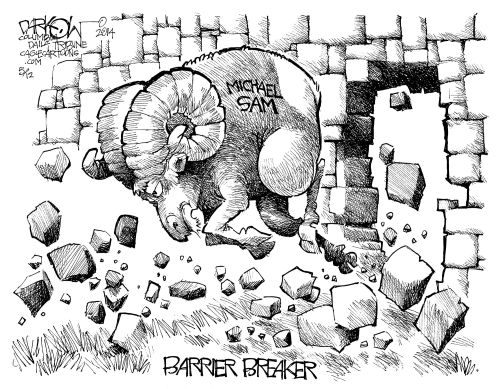

John Darkow (columbiatribune.com)

Readers familiar with the story will know that Michael Sam was drafted by the St. Louis Rams. This cartoon by Darkow communicates a similar message to the cartoon by Keith Knight (above), that race and sexual orientation should somehow be subsumed in the general meaning of the cartoon and that the ‘simple’ fact of the draft should be highlighted. One major difference is that the Darkow comic relies on metaphor and the Knight comic is a more literal representation. In fact, ‘Barrier Breaker’ is drawn in such a way that it erases all mention of sexual orientation and it erases all mention of race. The metaphor of a ram breaking through a wall is clear to the reader only if the reader already knows the discourses that play a role in the Michael Sam case. (Under other circumstances we would need to consider underlying or implicit prejudicial messages: the jokes that could be told about a gay man joining a team called the Rams; the jokes that could be made about a black man being represented by a ram.)

It is no surprise, of course, that cartoonists would choose to highlight certain aspects over others. The intersections of race and of sexual orientation in this particular situation—professional sports in the U.S.—are a virtual minefield. Is it safer for cartoonists to create a more literal representation than it is to create a metaphorical representation? Is it simply too difficult to navigate the issues metaphorically? Understanding political cartoons is a complex act of reading that draws on multiple types of literacies and relies on a vast array of knowledge and cultural discourses. Likewise, creating cartoons demands that artists focus on some aspects of an issue or story and leave out other aspects.

I ask readers of Pencil Panel Page and Hooded Utilitarian to provide their own examples of cartoons regarding Michael Sam or regarding similar situations. How do race and sexual orientation function in the commentary of political cartoons?