(1) Even before you see the movie it seems like you’ve seen it. This isn’t only because Mark Boal’s screenplay is so sparse—under 10,000 words, apparently—that almost all of its memorable lines and moments are in the previews, largely in chronological order. No. Before you’ve seen Zero Dark Thirty, it’s likely that you already have some knowledge of and feelings about the film, thanks to a wide-ranging debate about whether or not ZD30 endorses torture.

(2) “As a moral statement, Zero Dark Thirty is borderline fascistic. As a piece of cinema, it’s phenomenally gripping — an unholy masterwork. The first masterstroke is the first thing you see — or, rather, don’t see. Under a black screen, the sounds of 9/11 build: a hubbub of confusion, reports of a plane hitting the World Trade Center, and then, most terribly, the voice of a woman crying out to a 911 operator who tries vainly to assure her she’ll be okay. She won’t be. That prologue looks like restraint — there are no sensationalistic images — but it’s cruel: The recordings are genuine. You want revenge so much it hurts, but you’ll have to live with the pain because the sonovabitch bastard Muslims who killed that poor woman are elusive, and when you catch them they won’t talk. The next scene, a brutal interrogation at a CIA “black site,” is unpleasant but not unwelcome. To paraphrase Dick Cheney, you sometimes have to go to the dark side, and the big, bearded Dan (Jason Clarke) has made the trip…” – David Edelstein, New York.

(3) “Portrayal is not endorsement.” – Kathryn Bigelow, director of Zero Dark Thirty.

(4) Kathryn Bigelow didn’t actually say that. She said something similar to it and I summarized it. I conflated her words into other words, to make her argument simpler and clearer. I’m actually owning up to that here. The creators of Zero Dark Thirty, Mark Boal and Kathryn Bigelow, do not do the same with their film. Instead, it begins with a title card saying that it’s Based On A True Story. “Just like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre!” I thought to myself.

(5) We live in a time inundated with “true” stories that are also “good” stories. Many of these stories turn out to not be true in the sense of factually accurate, even as their creators will claim that they are true in the sense of “getting to an emotional/personal/spiritual/political/etc. reality.” Ultimately, true can have a lot of meanings. So, it turns out, can good.

(6) Right after the title card, the film cuts to a black screen with audio of real phone calls from inside the towers on 9/11. Whatever emotional purpose this serves—I was in New York on 9/11, and was so horrified by this sequence I nearly left the theater—there’s a signaling purpose here. This Is Real, the phone calls attest. This Happened. In a way, the phone call sequence abrogates the hedging of “based on a true story.” It sets up a tacit contract that we’re getting at something close to the truth. This was only reinforced by the misguided and self-important pre-release decision on Boal and Bigelow’s part to portray the movie as somehow a just-the-facts-ma’am depiction of the hunt for Bin Laden derived from their exclusive “journalistic” access to people involved.

(7) I should probably just note here that several characters in ZD30, including its protagonist, are composites. In other words, they don’t exist and stand in for groups of people. This is in line with other Based On A True Story narratives, but also worth noting.

(8) It seems in ZD30’s case that the multiplex and not the newspaper is going to be the first draft of history. Many more people have already seen Zero Dark Thirty than will ever read Mark Bowden’s The Finish, an actual-nonfiction prose account of the same story. Does this increase the film’s obligation to get the facts right? Or is its higher obligation to be a compelling work of quality cinematic entertainment? Or art, for that matter? Without the pre-release interview blitz on Bigelow and Boal’s part, would this obligation have changed? What, in other words, is the value of the truth here?

(9)Creative Nonfiction, the genre of writing I largely work in, is an odd beast, engaging with complementary, occasionally competing, systems of worth. On one level, there’s the aesthetic worth of a particular work, and on the other there’s its truth value. The truth is a difficult beast. The work we create is both enhanced and restricted by it. Audiences and readers are far more forgiving of narrative structure issues (for example) in true stories because they are true, because on some level we recognize that fictional narratives are able to “cheat” in order to satisfy us. Works with a high level of truth value can often get away with being on some level aesthetically unsatisfying, while works that are exquisitely crafted are often able to elide some of the problems of the truth, be they gaps in memory, or conflicting accounts, or a baggy structure, or what have you. Part of what is at work with Zero Dark Thrity’s first five minutes and with Boal and Bigelow’s publicity tour is an attempt to sell you on the work’s truth value prior to your having any experience of its aesthetic one.

(10)Were it not for this, I do not believe the debate over the use of torture in the film would be occurring. Were the film about a CIA agent pursuing, say, Homeland’s Abu Nazir, with a 9/11-like terrorist attack in the first shot, I don’t think anyone would care, not really. More importantly, they wouldn’t be so sure that they were so sure about the film’s stance towards torture, as ZD30 isn’t nearly as cut and dry as everyone seems to be pretending it is.

(11)The case against torture—one I find persuasive, to be clear—rests on two arguments: morality and effectiveness. Simply put: Torture is wrong and it doesn’t work. These aren’t completely separate. While we’re all fond of the expression the ends don’t justify the means, the truth of the matter is we often make decisions about morality and ethics based on whether or not a specific end is worth a specific mean. So one of the reasons why torture is wrong is because it doesn’t work. The ends—shoddy intel, innocent people destroyed, the dehumanizing effect on the torturer, the cost to our moral standing etc.—aren’t worth whatever crumbs we’d get from torturing people. It’s helpful then to think about Zero Dark Thirty in terms of both of these standards. Does it portray torture as effective? And how does it portray it morally?

(12) The answer to the first question is complicated, but I believe that the movie has its thumb on the scale in favor of torture’s effectiveness.

(13) ZD30 is divided into roughly two halves, one about the CIA’s failure to find Bin Laden, and one about its success. The torture takes place entirely during the “failure” half of the film, and there are many moments in this half where it’s made at least tacitly clear that the CIA isn’t getting anywhere with torturing people. Also, the one piece of important intel—the name of Bin Laden’s courier—comes as the direct result not of torture but rather from an old interrogation room bluff: Jessica Chastain’s Maya and Jason Clarke’s Dan convince a detainee that he has already helped them and he gives them the name.

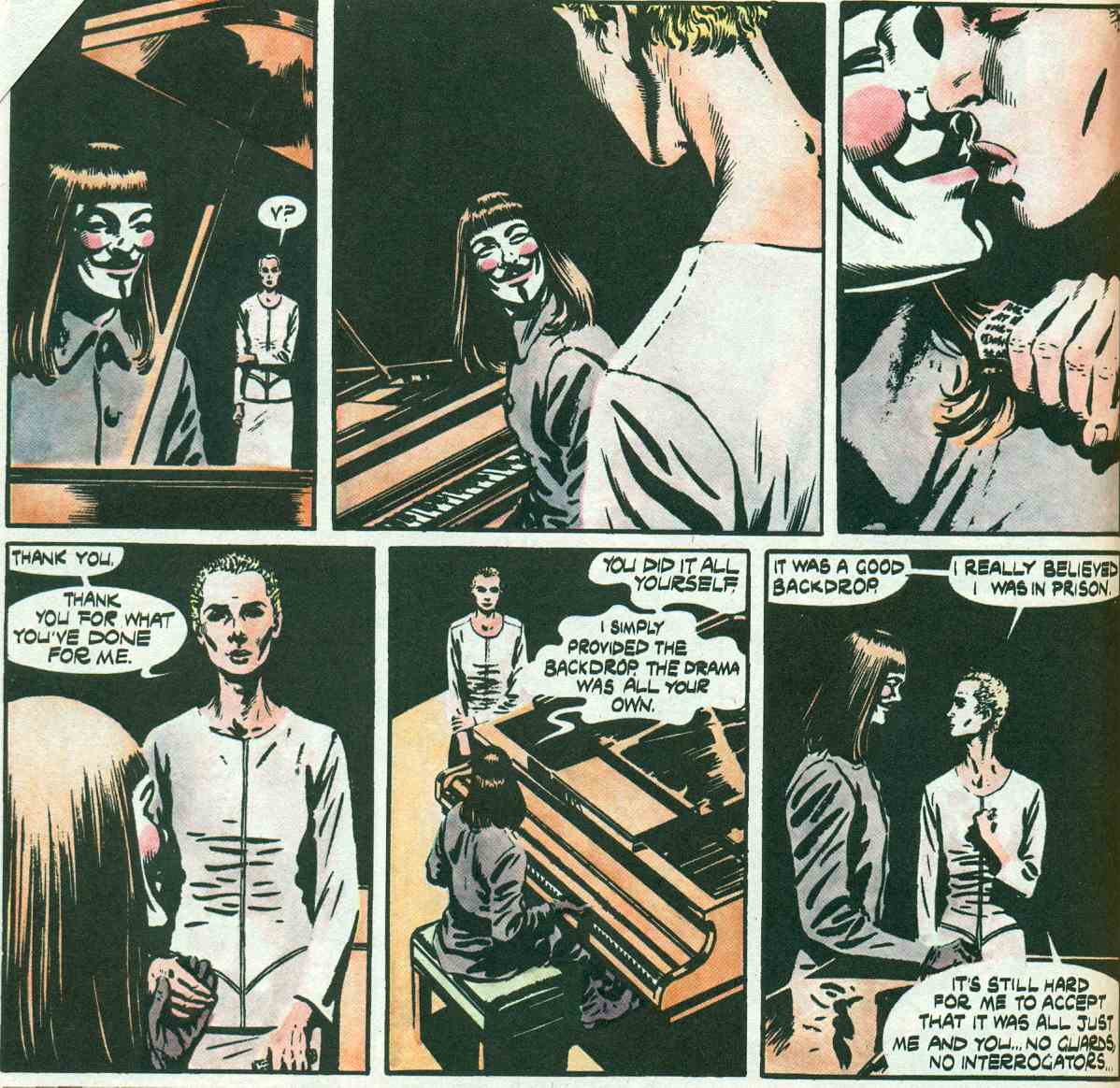

(14) It’s easy to point to this and say “see, the film is showing that old school law enforcement tactics work and torture doesn’t,” and, indeed, some have. The problem is that this bluff only works because the detainee has been waterboarded, starved, sleep deprived, beaten, walked around like a dog and shoved in a small wooden box until his short-term memory has disintegrated, allowing them to convince him that he has forgotten helping them. Later on, Maya interrogates a different detainee who says without prompting, “I don’t want to be tortured anymore, I’ll tell you whatever you want.” He provides no useful information, but he provides the next moment of narrative satisfaction to the audience, by intoning the ominous line “he is one of the disappeared ones.” Torture is thus narratively effective in the film regardless of how effective it is as an intel-gathering tool.

(15) Oh yeah, there’s also the glaring fact that torture did not, in real life, get us the name of the courier.

(16) “‘The film creates the strong impression that the enhanced interrogation techniques that were part of our former detention and interrogation program were the key to finding Bin Laden,’ acting CIA Director Mike Morell wrote in a letter to employees in December. ‘That impression is false.’ The Senate intelligence committee, which last month completed a 6,000-page report on the CIA interrogation program based on its examination of 6 million pages of CIA records, was more definitive: ‘The CIA did not first learn about the existence of the UBL courier from CIA detainees subjected to coercive interrogation techniques. Nor did the CIA discover the courier’s identity from CIA detainees subjected to coercive techniques.’ Yet in their film, Bigelow and Boal depict the exact opposite.” – Adam Serwer, Mother Jones.

(17) “Torture may be morally wrong, and it may not be the best way to obtain information from detainees, but it played a role in America’s messy, decade-long pursuit of Osama bin Laden, and Zero Dark Thirty is right to portray that fact.” – Mark Bowden.

(18) The film also contains many moments where characters go to bat for the efficacy of torture and not one moment in which anyone repudiates it. This would be excusable by the dictates of realism (it’s doubtful CIA torturers would sit around talking about how it doesn’t work) were it not for the film’s inclusion of a scene where Mark Strong’s “George” argues that torture works to Stephen Dillane’s “National Security Advisor”—a guy who is fairly clearly based at least in part on White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emmanuel, by reputation the most argumentative man alive—and NSA/Rahm doesn’t argue about it.

(19) Regardless of its view on torture’s effectiveness, there is the question of ZD30’s take on the morality of torture. And it is here that the movie is at its most troubling, if most interesting. For Zero Dark Thirty has absolutely no moral perspective on torture. It’s an essentially amoral film. It’s not immoral. It’s view towards torture is not, say, 24’s, where it always works and is always awesome and the people who get tortured deserve it. Nor is it, say, Man on Fire where torture is the hilariously over the top and necessary path that Denzel Washington must take to find Dakota Fanning.

(20) In Zero Dark Thirty, torture is simply shown, generally in a filmic style we associate with “objectivity”: no underscoring, documentary-like cutting and camera movement, few POV shots, etc. Much has been made of a few quick shots of Maya wincing, folding her arms, or otherwise seeming to disapprove of the interrogation she’s seeing. Yet, given that we later learn that in these first scenes she is at most 22 years old, and given that eventually she embraces torture, these moments can also be read as the squeamishness of the Rookie Cop who is about to become the Lone Crusader Who Works To Buck The System, Jimmy McNulty with better bone structure.

(21) Does Zero Dark Thirty have some kind of obligation—moral, political, ethical—to take a stance on torture, to be a “good” story in a moral sense? How would we treat a mainstream Oscar-nominated thriller that treated the Holocaust or slavery in a similarly “objective” and amoral way? Or a film that did the same with rape? Why doesn’t torture, a very recent part of our history that is still being debated, belong in this group?

(22) Ultimately, these questions are far more interesting than the film itself, which may be why the debate over torture has obscured discussion of the actual film. The script, alas, is a clunker, filled with tin-eared lines, containing characters that lack even one dimension, and riddled with clichés, while the acting—particularly the dialect work from the film’s many British actors—is deeply uneven.

(23) Despite this, the film has a power, thanks in part to Kathryn Bigelow. Zero Dark Thirty is expertly, even brilliantly, directed. Each sequence in it is riveting in its construction as Bigelow uses her keen sense of color, light and rhythm to pull the audience through the film’s decade-long story. Its second source of power is, of course, that it is true. Or rather true-ish. Or truthy. From the moment those phone calls start in, you can’t help but think that everything they’re showing you really happened, even when a part of you screams that it didn’t. This is Zero Dark Thirty’s trick, and it’s a good one. It can justify its weaknesses through claiming a level of access to the people involved in the story that you the viewer will never, can never, have, while also changing things when necessary for the sake of being a good story. The end result is something neither particularly true nor particularly good that somehow feels like both. And if feeling is a kind of truth, maybe, at the end of the day, it is both of these things.