In 1986, Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns both appeared in serialized form, and Art Spiegelman released the first volume of Maus. The graphic narrative has had many high points over the years—the graceful aesthetics of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland; the modernist playfulness of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat; the rise of the counterculture in Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix—but 1986 was remarkable.

In 1986, Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns both appeared in serialized form, and Art Spiegelman released the first volume of Maus. The graphic narrative has had many high points over the years—the graceful aesthetics of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland; the modernist playfulness of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat; the rise of the counterculture in Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix—but 1986 was remarkable.

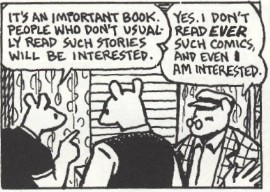

At the time the American comic book scene was dominated by angsty mutant teenagers and anthropomorphic animals: aardvarks, turtles, hamsters. Miller and Moore’s works reinvented the superhero genre, using it to question rather than reify authority. But as serious, dark, and dystopian as those books are, they didn’t change the landscape of graphic narrative the way Maus did. Spiegelman wrote about the Holocaust. In doing so he demonstrated that comics, which always labor under the onus of being dismissed as children’s fare, can grapple with the weightiest topics. Maus made it possible for the Alison Bechdels, the Joe Saccos, the Marjane Satrapis—current authors who address complex political and social issues—to thrive.

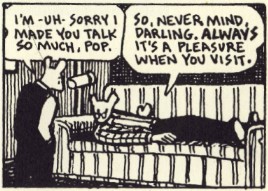

What makes Maus a particularly complex and rewarding political narrative is that it conveys both the horror of the Holocaust and the ways in which that horror ripples down through generations. Part of the vastness of the Holocaust is that it didn’t really stop with the end of World War II. Trauma was transmitted through to the children and grandchildren of survivors. Spiegelman relates his father Vladek’s stories about his life in Nazi-occupied Poland and his survival in Auschwitz and Dachau, but this is as much Art’s story as it is Vladek’s. Spiegelman uses two parallel narratives to capture the multi-generational valence of trauma: in one, Vladek’s story, we get a picture of the fear and misery associated with life in the Jewish ghettos and the Nazi concentration camps; in the other, a meta-narrative about Art interviewing Vladek in order to write Maus, we see how the Holocaust continues to affect their lives.

What makes Maus a particularly complex and rewarding political narrative is that it conveys both the horror of the Holocaust and the ways in which that horror ripples down through generations. Part of the vastness of the Holocaust is that it didn’t really stop with the end of World War II. Trauma was transmitted through to the children and grandchildren of survivors. Spiegelman relates his father Vladek’s stories about his life in Nazi-occupied Poland and his survival in Auschwitz and Dachau, but this is as much Art’s story as it is Vladek’s. Spiegelman uses two parallel narratives to capture the multi-generational valence of trauma: in one, Vladek’s story, we get a picture of the fear and misery associated with life in the Jewish ghettos and the Nazi concentration camps; in the other, a meta-narrative about Art interviewing Vladek in order to write Maus, we see how the Holocaust continues to affect their lives.

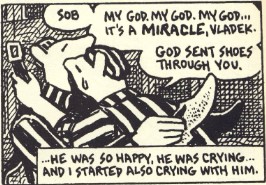

Each of these parts is important. The historical narrative is a powerful account of the Holocaust. There are many reasons why comics proved a perfect medium to capture Vladek’s experiences. Spiegelman’s stark black-and-white images have the unwavering lens of a documentarian; he uses the graphic medium to render the Nazi’s atrocities visible. We see Jews hanging from the gallows, German soldiers bashing children against walls, concentration camp prisoners forced to light other prisoners on fire. Moreover, the striking visual metaphor of representing Jews as mice and Germans as cats adds intriguing iconic layers to the narrative.

The contemporary narrative works as a framing device, but it would be a mistake to see it only as a delivery system for the “main” narrative. Maus is as much a question of how we continue to live after trauma as how we survive it. When Vladek tells his own story, he is heroic. He is not only a survivor but practically a Hollywood star. “People always told me I looked just like Rudolph Valentino,” Vladek tells Art. Vladek in the narrative present, however, is hard to live with. Many of the same qualities that make Vladek the hero of his own story make him something of an antagonist in Art’s story. Thrifty becomes stingy, determined becomes stubborn, cautious becomes paranoid. Vladek has carried those traits with him long after they are needed for survival. Now, they get in the way of his relationships. In a short prologue to the first book, a young Art falls down and is teased by his friends. When he runs crying to his father, Vladek doesn’t console Art. Instead, he says, “Friends? Your friends? … If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week … then you could see what it is, friends!” He hasn’t managed to move out of the concentration camps. But is Art allowed to hold this against him?

The contemporary narrative works as a framing device, but it would be a mistake to see it only as a delivery system for the “main” narrative. Maus is as much a question of how we continue to live after trauma as how we survive it. When Vladek tells his own story, he is heroic. He is not only a survivor but practically a Hollywood star. “People always told me I looked just like Rudolph Valentino,” Vladek tells Art. Vladek in the narrative present, however, is hard to live with. Many of the same qualities that make Vladek the hero of his own story make him something of an antagonist in Art’s story. Thrifty becomes stingy, determined becomes stubborn, cautious becomes paranoid. Vladek has carried those traits with him long after they are needed for survival. Now, they get in the way of his relationships. In a short prologue to the first book, a young Art falls down and is teased by his friends. When he runs crying to his father, Vladek doesn’t console Art. Instead, he says, “Friends? Your friends? … If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week … then you could see what it is, friends!” He hasn’t managed to move out of the concentration camps. But is Art allowed to hold this against him?

And this is ultimately the brilliance of Maus. Had Spiegelman only told the one narrative, his father’s survivor’s tale, it would have been horrifying but sterile. It would have felt like a history lesson. By allowing his characters to be real people—frail and heroic, petty and generous—the Holocaust narrative comes to life.

Jeffrey Chapman is an Assistant Professor of English at Oakland University.

NOTES

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman received 28.125 votes.

The poll participants who included it in their top ten are: Edmond Baudoin, Corey Blake, Scott O. Brown, Bruce Canwell, Jeffrey Chapman, Hillary Chute, Barry Corbett, Mike Dawson, Joshua Dysart, Larry Feign, Jason Green, Patrick Grzanka, David Heatley, Jeet Heer, Bill Kartalopoulos, T. J. Kirsch, MariNaomi, Jason Michelitch, Eugenio Nittolo, Jim Ottaviani, Joshua Paddison, Marco Pellitteri, Giorgio Salati, Matthew J. Smith, Nick Sousanis, Matteo Stefanelli, Ty Templeton, Kelly Thompson, and Qiana J. Whitted.

Joshua Dysart specifically voted for RAW, which resulted in a 0.125 vote for Maus.

Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale has its origins in a three-page story by Spiegelman from 1972. The story, also titled “Maus,” was initially published in the comic-book anthology Funny Animals, edited by future Crumb and Ghost World film director Terry Zwigoff. The “Maus” short has been reprinted a number of times, most recently in Breakdowns/Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, a hardcover collection of various Spiegelman comics shorts published by Pantheon Books.

After the original “Maus” was published, Spiegelman reconceived the material. In 1981, he published the first chapter of the current Maus in the second issue of RAW, a comics anthology he edited with his wife Françoise Mouly. (Mouly is presently an art director for The New Yorker magazine.) All but the final chapter of Maus was serialized in RAW between 1981 and 1991.

In 1986, Pantheon Books published a book collection of the first six chapters subtitled “My Father Bleeds History.” It was a critical and commercial success. It also received a National Book Critics Circle Award nomination in the category of Biography/Autobiography. Maus was the first comics work to receive recognition from this awards program.

In 1992, Pantheon published a book collection of the remaining chapters of Maus, including the heretofore unpublished final chapter. It was subtitled “Part II: And Here My Troubles Began.” This collection was also a critical and commercial success. Spiegelman again received a National Book Critics Circle Award nomination for Biography/Autobiography. He also won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Fiction.

In 1993, with awards presented for work published in 1992, Spiegelman and the completed Maus received a special Pulitzer Prize. It was the first (and to date only) Pulitzer given to a comics work outside the Editorial Cartooning category.

The book is a mainstay of high-school and college English courses. It can be purchased in either the two paperback collected editions or as a single hardcover that combines the two paperbacks. These editions can be found at virtually any bookstore or online retailer. Prospective customers should note that bookstores frequently stock the book in the Judaica section. One can also find the book in the biography section of virtually any public library.

–Robert Stanley Martin