Six miles away from my office is a theater that plays Bollywood movies simultaneously with their Indian release. This is one such film.

***

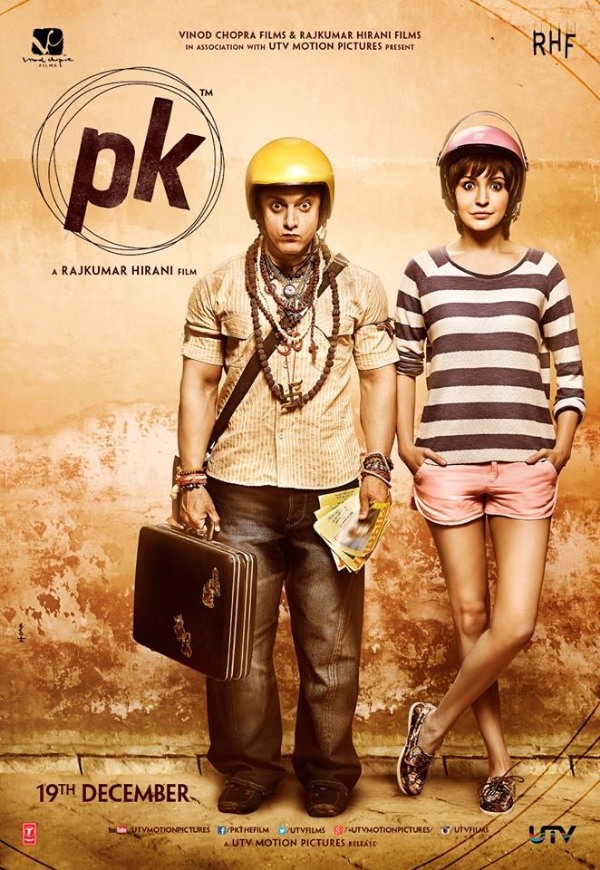

PK

Directed by Rajkumar Hirani, 2014

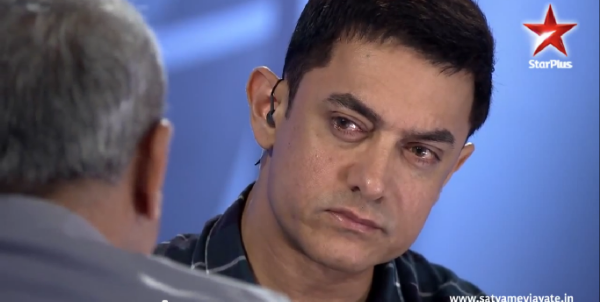

“I think it’s high time we creative people in the film industry stop and think what we teach our children, the audience, and the future generation through our films.” – Aamir Khan, Satyamev Jayate, Nov. 9, 2014

—

The first thing you ought to know about PK is that it is the highest-grossing film in the history of Indian cinema; in fact, if you want to get boorishly local about it, liberal estimates mark it as the first Indian film to have breached the classic barricade by which to cordon pretenders off from the rarefied seats of Hollywood success: it has grossed in excess of $100 million. Indeed, at just over $10.5 million collected in the U.S. & Canada, PK is also the highest-grossing foreign-language film to have screened in English-speaking North America in 2014, and its global expansion is not quite done – a 3,500-screen wide release is now planned for China.

The second thing you ought to know about PK is that it’s a broad religious satire starring a Muslim celebrity, which has not exactly been the consensus image conjured by the international media from combining religion and satire in recent weeks – but then, Hindi film is so big a place that most in western arts reportage find it easy to just relegate the whole thing to specialist tastes, even when its successes burn historically bright.

And few are less unfamiliar with success then Aamir Khan.

As with many Bollywood stars, Khan is a scion. Both his uncle and his father produced and directed films, the former slotting him into his screen debut at the age of eight and subsequently producing his adult star breakthrough: Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, a romance directed by one of Khan’s cousins in 1988. Soon, Khan became renowned as a lucrative ‘chocolate boy’ — very sweet, much-desired — even while he developed a reputation as a perfectionist, appearing in relatively few films per year. He first came before the eyes of international art house aficionados in 1998, when he appeared in Indo-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta’s Earth; Roger Ebert gave it three stars, but this was nothing compared to what was to come.

In fact, if you’re like me — an English-speaking North American over the age of 30 — the first Bollywood film you ever heard a *lot* of critics discussing was surely 2001’s Lagaan, an unexpected global sensation big enough to catapult India toward a rare Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film; it was also Aamir Khan’s debut as a movie producer. He subsequently grew yet more remote, going completely inactive from the years 2002 through 2004 for personal reasons, only to return as frontman for a series of ambitious projects, the most notable-in-retrospect being 2006’s Rang De Basanti, a resolutely populist account of political awakening among a tidily diverse set of college chums.

Never mind that the noticeably 40-year old Khan was playing a character just under half his age, aided mainly by a floppy hairdo akin to Martin Freeman’s in the Hobbit trilogy; the film’s potent depiction of extremely close friendships transfigured through patriotic opposition to sociopolitical ills, up to and including political assassination, struck a chord with the filmgoing public. A 2008 thesis paper by one Meghana Dilip of the University of Massachusetts Amherst provides several examples of subsequent real-life protests fashioning themselves after events from the film, as well as some analysis of the film’s aggressive marketing: carefully tailored to enhance the work’s prestige as a venue for social messaging while also functioning as effective advertising for brand partners.

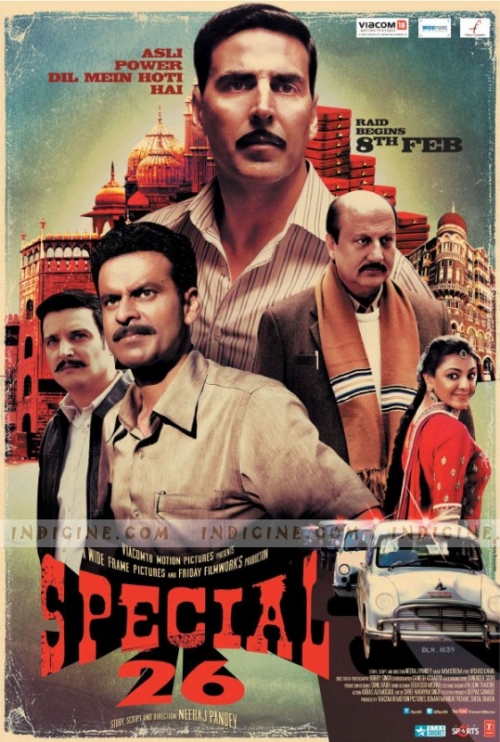

This was the path Khan would subsequently follow. In 2007 he would make his directorial debut with Taare Zameen Par (aka Like Stars on Earth), an ‘inspirational teacher’ drama concerning childhood dyslexia distributed in English environs by Disney. In 2008 came Ghajini, a vaguely arty revenge thriller reminiscent of Christopher Nolan’s Memento which became the highest-grossing Indian film ever, and remained so until it was dethroned by Khan’s next starring project: 2010’s 3 Idiots, an inspirational comedy about engineering students directed by Rajkumar Hirani, about whom more will be mentioned shortly. Other films would then vie for the heavyweight title, even temporarily gaining the lead, but all were swept away in 2013 by a tidal wave of kitsch – the riotously chintzy crime thriller-cum-global financial crisis parable Dhoom: 3, which marked the *third* time in half a decade that Aamir Khan had starred in the highest-grossing film in all the history of Indian cinema.

And hey – this isn’t to say that every film starring Khan was a popular bonanza. But even as the likes of Dhobi Ghat (2011, lyric ensemble drama about life ‘n shit) and Talaash (2012, very serious cop drama about regret ‘n shit) failed to set records, Khan was planning his next big move in social justice entertainment. It was not enough to be the Quality Superstar. He was going to be the Oprah of India.

Satyamev Jayate debuted on May 6, 2012, airing simultaneously on national and cable networks on late Sunday mornings to maximize family viewership. It has since run 25 episodes across three seasons, dubbed into numerous languages and streamed online with English subtitles. Each show adopts a discreet topic: domestic violence; alcoholism; dowry; road safety; LGBT acceptance; tuberculosis; caste; toxic masculinity. The aim, generally, is social hygiene via slick suites of emotional appeal, with creator/co-producer Khan seated before a studio audience, coaxing tales of trial and triumph out of guests from across India. The host weeps openly seemingly once per episode, but his tears are not shed for nothing; each broadcast also offers a poll by which viewers can SMS a vote and a small donation to one or more specially designated non-governmental organizations, thus ensuring a tangible result while the credits roll. It was all a huge enough success that season 3 added a subsequent hour-long live show after each episode, in which Khan would interact with viewers on the applicable issue.

And it was into this context — premiering, in fact, the very month after the final episode of season 3 — that PK arrived. By this time, Khan had made extremely explicit his feelings on Bollywood’s propagation of objectified women and aggressive, thoughtless men, and there was really no better filmmaker with whom he could have collaborated in opposition to that than Rajkumar Hirani, of the aforementioned 3 Idiots. Faultlessly dignified and widely successful, Hirani made his name on the Munna Bhai series of comedies, the second of which (Lage Raho Munna Bhai, 2006) had prompted an interest spike in Gandhism, not unlike the observable social impact of the roughly contemporaneous Rang De Basanti – was it fate that brought Khan and Hirani together?

Perhaps it was good business sense. Hindi film has enjoyed a long history of popular movies dedicated to educating the public on social issues; Hirani, for example, is an avowed fan of an earlier social film exemplar, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, though it is Hirani’s works with Khan which have found the most success with such films right now, in an era of grander financial scale and especially meticulous marketing. Hirani readily states that the film came specifically from “a desire to say something,” message-wise, rather than any specific storytelling goals, which perhaps added a special dose of calculation to the project’s timing. It follows an earlier religious satire, 2012’s OMG – Oh My God!, which director Umesh Shukla based on both an Indian play and a 2001 Australian comedy, The Man Who Sued God; undismayed by the similarities, Shukla would come to deem his and Hirani’s works dual entries in a genre, and perhaps we should think of it in terms of generic devices, as a means of best divining its message.

As PK opens, Aamir Khan is introduced as a humanoid space alien arriving nude on Earth; this is possibly inspired by another Australian film, 1995’s Epsilon (aka Alien Visitor), but Hirani and co-writer Abhijat Joshi draw from the wider global pool of fish-out-of-water entertainment: no sooner has Khan arrived on terra firma than his shimmering remote beacon is snatched by a thief, leaving him stranded in the midst of humanity with no pants on his ass and no way for his spacecraft to pick him back up.

MEANWHILE, IN EXOTIC, FARAWAY BRUGES, Anushka Sharma plays a young Indian woman who tumbles into a ruthlessly cute relationship with a Pakistani man; alas, no sooner has their obligatory romantic montage/song sequence ended than Sharma’s parents, beholden to a charismatic Hindu godman, voice their religiously-motivated doubts as to the endurance of any conceivable relationship with a *gasp* *choke* Muslim. The couple nevertheless plans to marry, but when the wedding day arrives Sharma finds herself alone, reading a Mysterious Note in which her love apparently severs their union and requests she never try to contact him again. Against all notions of common sense, she doesn’t, and returns heartbroken to Delhi to pursue work at the home of the emotionally destroyed: television journalism.

Sharma, as I’ve noted before, can be an entertaining presence; like a utility player from the bygone age of American studio films, she plays basically the same character in every movie, modifying her good-hearted effervescence from ‘extremely bright’ to ‘actually blinding’ as the role demands. She’s pretty subdued here, perhaps out of respect for Khan’s full-bodied schtick as the alien, PK – so named for his eccentric and questioning ways, as ‘peekay’ is a term suggesting drunkenness, which everyone assumes is this crazy guy’s problem. Staggering around with jug ears and ill-fitting stolen clothes, his eyes straining so as never to blink on camera (it’s alien!), his muscles bulging from the physical conditioning Khan presumably underwent to look good in nude scenes, his mouth lipstick-red from constantly chewing paan, PK may look like a professional wrestler lost between gimmicks, but he’s not tipsy; he just wants to find his damn beacon, which has regrettably fallen into the hands of a religious leader who’s passing it off as a divine object. Could this be the same godman who messed up Sharma’s romance? Might the alien and the journalist team up to expose religious shenanigans in India?! Have you ever seen a movie? Like ever??

The heart of PK is in the alien’s observations about life in this crazy mess called a country. Humans make love in private, but make war in public! You know. Midway through the first half, Khan relates to Sharma a long flashback about how he learned the ways of the human; aliens communicate telepathically, but they can also download another entity’s store of knowledge through prolonged physical contact, so many (many) jokes are devoted to PK attempting to hold the hands of random men and women, only to be aggressively rebuffed. Message-wise, this functions in two ways. PK *is* certainly behaving inappropriately, but he’s also an innocent, an adult child, so the audience simultaneously feels sorry about the men exploding in homophobic rage, though they might also sympathize with their gay panic, given that men holding hands is such an extraterrestrial abberation. Similarly, the audience may feel the women are right to fend off the unwanted advances of a strange man, though aren’t they overreacting just a little? PK the alien only wants to be nice, and so PK the movie has it both ways, playing into social norms as a means of sugaring the pill – perhaps with so much additive that the medicinal effect is nullified.

A similar trick occurs when Khan begins inquiring as to religion, having heard that God is in charge of India, and reasoning that He, of all people, must know where to find his beacon. But oh – all these religions are contradictory! The gods must be crazy! The Catholics drink wine at mass, but when PK tries to bring some booze to the mosque, he’s chased away by an angry mob… segueing into a montage of every major religion pursuing him in a similarly outraged manner. Balance is the key.

Balance might also be a necessity. Feature films screened in India must undergo censorship via the Central Board of Film Certification. Guidelines promulgated by the Central Government pursuant to the Cinematograph Act of 1952 provide that films must avoid “visuals or words contemptuous of racial, religious and other groups.” Indeed, the presence of censorship has occasionally been invoked to shield PK from religious and political argumen; check any well-populated comments section of an internet post relating to the film, and you’ll see plenty of accusations that Hirani is kissing Muslim ass, that Khan is concern trolling the Hindu majority, that the film’s treatment of various faiths are, in fact, wildly unbalanced, etc. But if a statutory body has already evaluated the damn thing for such offense, the argument goes, what legitimate grievance can you have?

Or let’s try another question: what is the PK philosophy of religion? Broadly, it cosigns the general theme of Shukla’s OMG – that religion should not turn so much on icons or intermediaries, but one’s personal relationship with the divine. Those of us in the U.S. (again: boorishly local) may find it not so dissimilar a take to that of evangelical Christianity, except the Indian films mean it to apply to all faiths, with none superior to another, distilled to their ‘essence’ so that the point where they are distinguishable is uncertain. OMG and PK, however, can be distinguished by the former’s insistence that there is, in fact, true divine power at work; Hirani & Joshi offer no such reassurance, pivoting instead toward a secularism where religions are but changes in costume; fashion. Very urbane, but cognizant of their audience. Only space aliens explicitly lack any religion in this film, which creeps right up to the precipice of agnosticism, but does not make the final leap, content to have its hero and his media enabler focus on exposing the chicanery of individual crummy religious representatives, thus inspiring a nationwide social media movement the filmmakers and star all but beg the audience to take into the real world. Hell, they did it before!

Now, I am not an alien, and I cannot read your mind, and you are not right here so that I can hold your hand, which I know you would let me, but I can nonetheless hear what you’re thinking. Of course this movie made $100 million, it’s a silly product! It’s safe! My god, a satire that makes every effort to avoid upsetting anyone! It’s a fucking sitcom!

Hirani, it must be said, is upfront about the cadence of his storytelling. “We are trying to make it simple so that it reaches as many people as possible, because in India you are talking about literacy levels which are from 0 to a 100.” It is similar to the careful packaging and broad distribution of Khan’s Satyamev Jayate – the intent is to be mass communication, with as wide a reach as possible.

Or, in other words, theirs is a cautious satire, wary of causing offense because the implication is that offense or aggression will cause the masses to turn away, and restrict the message, then, to like-minded souls (who don’t need it) or interested opponents spoiling for a fight. They will be the voice of reason, thus accessing the undecided, the busy, the unpracticed; from there spreads the vine. What does a Presidential candidate do in a U.S. general election? Move toward the center. Hirani, Joshi & Khan, then, if you’ll allow a pun, are truly political artists, operating on just as prominent a nationwide level, and raking in returns befitting a chief executive.

But maybe something else is happening too.

It is about half an hour from the end when the religiopolitical indistinctness of PK suddenly reaches a tension so acute that it becomes fascinating. Khan is preparing to debate his godman nemesis on live television, with the former’s beacon and the latter’s reputation on the line, when he is contacted by a good-hearted lowlife friend played by Sanjay Dutt, who also starred as the good-hearted lowlife protagonist of Hirani’s earlier Munna Bhai series – truly this film has dotted every i and crossed every t. Dutt has found the thief that stole Khan’s beacon, thus disproving the godman’s claim to the item’s ownership/divinity, but before this news can be disseminated a bomb blast rips through the train station, killing both the thief and Dutt.

The film never confirms who did it. However, when the cameras start rolling on the big television event — any similarities drawn between it and a certain actual show featuring Aamir Khan are yours to draw — the godman is hardly disinclined from pointing out that perhaps ol’ PK’s inquisition has proven counterproductive; I mean, he’s certainly not happy that people died, it’s an awful tragedy, of course, but maybe also a teachable moment, because, y’know, certain groups just can’t handle criticism like that. Eager to demonstrate the insights his close relationship with the beyond have brought, the godman also brings up the whole unfortunate incident of Anushka Sharma’s punctured romance, which finally moves Khan to action. He’s touched Sharma, you see. Heck, he’s in love with her! But in downloading her thoughts, he was also able to ascertain the truth behind her hidden sadness. That Muslim boy didn’t send Anushka Sharma a Mysterious Note breaking off their wedding at all! Anushka Sharma read the wrong note by accident! That boy was still crazy about her, AND IF YOU GET ON THE PHONE RIGHT NOW, ANUSHKA SHARMA, ON THE PHONE TO BELGIUM LIVE ON THE AIR, YOU’LL FIND OUT THAT YOUR MAN HAS BEEN CALLING THE EMBASSY OF PAKISTAN EVERY SINGLE DAY FOR MONTHS AT A TIME TO SEE IF YOU’LL EVER COME BACK!

Needless to say everybody pretty much shits themselves at this point, while the godman can only glower. He has been totally defeated – hoisted with his own petard. His own disciple, Sharma’s father, grabs the beacon from his hands. The charming thing about PK is that its stakes are pretty low; the godman isn’t a supervillain, he’s just a liar and a petty tyrant, managing his fiefdom through compelling narratives that exploit social fears to widen divisions, and thus reduce the risk of incursion onto the feifdom. Do not trust Muslim men with Hindu women; the man will leave. If the godman truly had divine access, he might have seen the cosmic game being played: this narrator, beaten by a better narrative. A ludicrous, goofy, contrived popular narrative, SO much more compelling than any of his recycled biases. Metaphorically, he has been destroyed by Bollywood. The prejudice of religion, ousted by movies. It is an aspirational vision for these filmmakers, this star. The assurance that they are doing more than making money.

The dream of art to save the world.