My first encounter of Berkeley Breathed’s Bloom Country was as a child, with a stuffed version of the character Opus. He was outfitted in reindeer antlers and shiny, plush Christmas ornaments. My sister and I did not know what to do with him. We were not sure what animal he was supposed to be. For the most part he looked like a penguin, but his beak, if it could be called that, was somewhat moose-like. Large, misshapen and skin-colored, this nose seemed adult– something that wasn’t meant for children to like or understand. It seemed inappropriate. All in all, the creature looked forlorn, but his holiday costuming looked jaunty, and fleshy, vaguely insidious schnoz. There were just too many layers going on at once. As conspicuous as a spy in a kid’s movie, Opus didn’t belong. He seemed to have other motivations for being there. He came from some world we didn’t recognize. He had baggage we couldn’t account for, and we found it difficult to overwrite his mysterious past for a game of ‘Life at the North Pole.’ We ignored and neglected him. Every year we unpacked him with the rest of the Christmas animals, placed him on a chair, and avoided him.

Now that I know Opus, and his attitude of beleaguered optimism, this strikes me as a little sad. Poor excluded Opus, a victim of branding. Yet there are advantages to being a cartoon icon. Comic strips are ephemeral. They are one of the few publications still discarded after reading. Perhaps due to a fluke in human brain functioning, their characters easily outlive their physical forms, or narratives. Some arcs and strips remain in the memories of certain readers, but cartoon characters become immured in a greater cultural context, with or without their original story lines. Opus made my sister and I uneasy, because while we could recognize him as a denizen of America’s collective unconscious, he demonstrated that we participated in this incompletely. On a related note, we continued to be confused as to why we saw so many urinating Calvins on a daily basis.

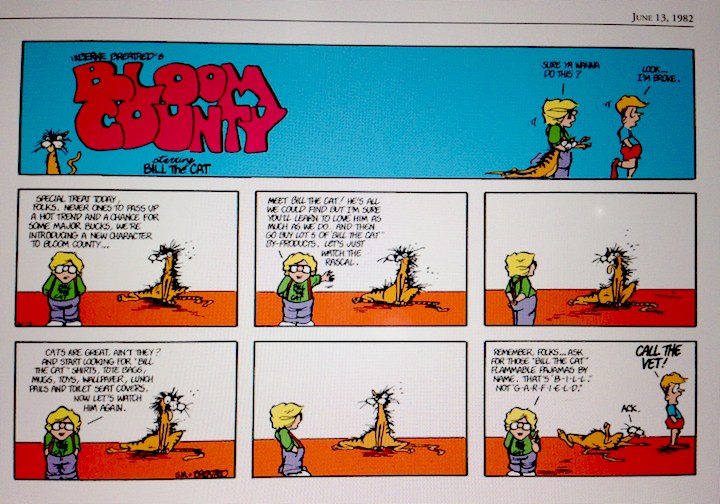

Opus is sort of a minor-league cultural artifact, a case of a mascot without rampant commercial licensing. It took a lot longer than I expected to discover my stuffed toy’s source material in daily life. My dad, a devotee of the strip’s original run, never purchased collections of Bloom County or its spinoffs. Neither Outland nor Opus ran in the Modesto Bee. I participated in the comics industry for years without stumbling upon them. I might have remained forever ignorant of the strip if not for earlier posts here on Hooded Utilitarian. Breathed makes his case in the Bloom County Library that he unwittingly pioneered pop-cultural references in comics, changing the landscape of the funny pages forever. Whatever influence he had, it’s not uncommon for ‘disruptive technologies’ to be forgotten in favor of more recent iterations. It’s harder to erase an iconic mascot, and their innate appeal. When done well, an icon exists in its own irreplaceable visual category. Opus looks uniquely like Opus, not like a generic cartoon penguin or moose. Opus is arguably the first visual element of Bloom County that uniquely belonged to it, and he’s a talking animal to boot. Breathed satirized mascots, and the merchandising death-spirals they inspire, in his Bill the Cat sunday strips, although he wasn’t above using them, either.

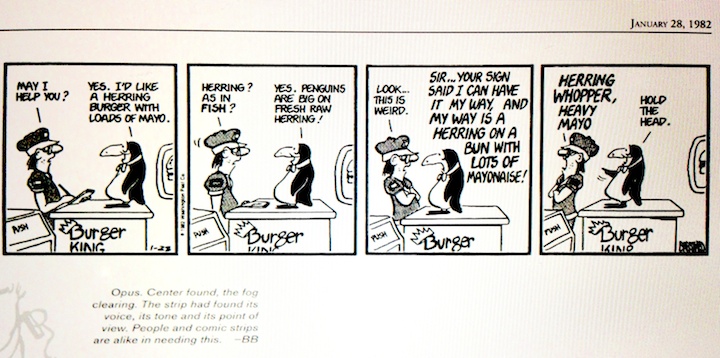

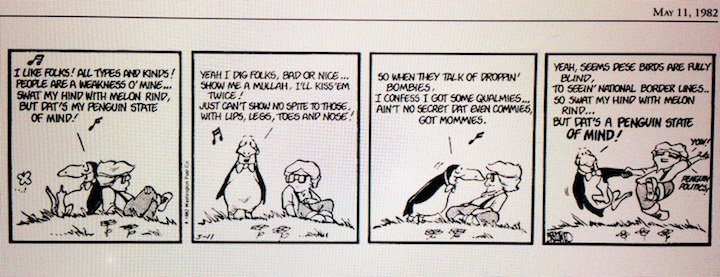

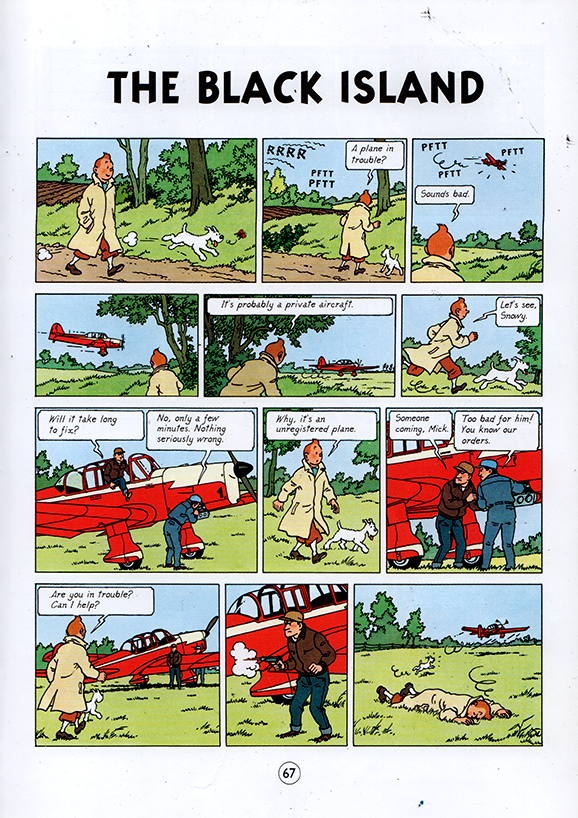

Opus becomes a mascot rather innocently. He doesn’t appear until six months into the run, and when he does, he looks like a standard penguin. In fact, when I asked at what point I should jump into the strip, Noah Berlatsky here at Hooded Utilitarian advised, “Few years in, maybe? When Opus starts looking like Opus is probably the way to go…” This echoes Breathed’s own commentary on the strip from January 28th, 1982, at around this point: “Opus. Center found, the fog clearing. The strip had found its voice, its tone and its point of view. People and comic strips are alike in needing this.”

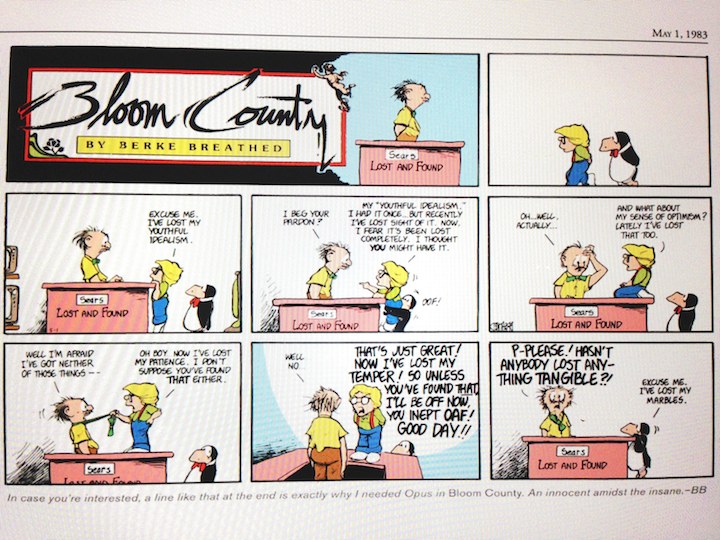

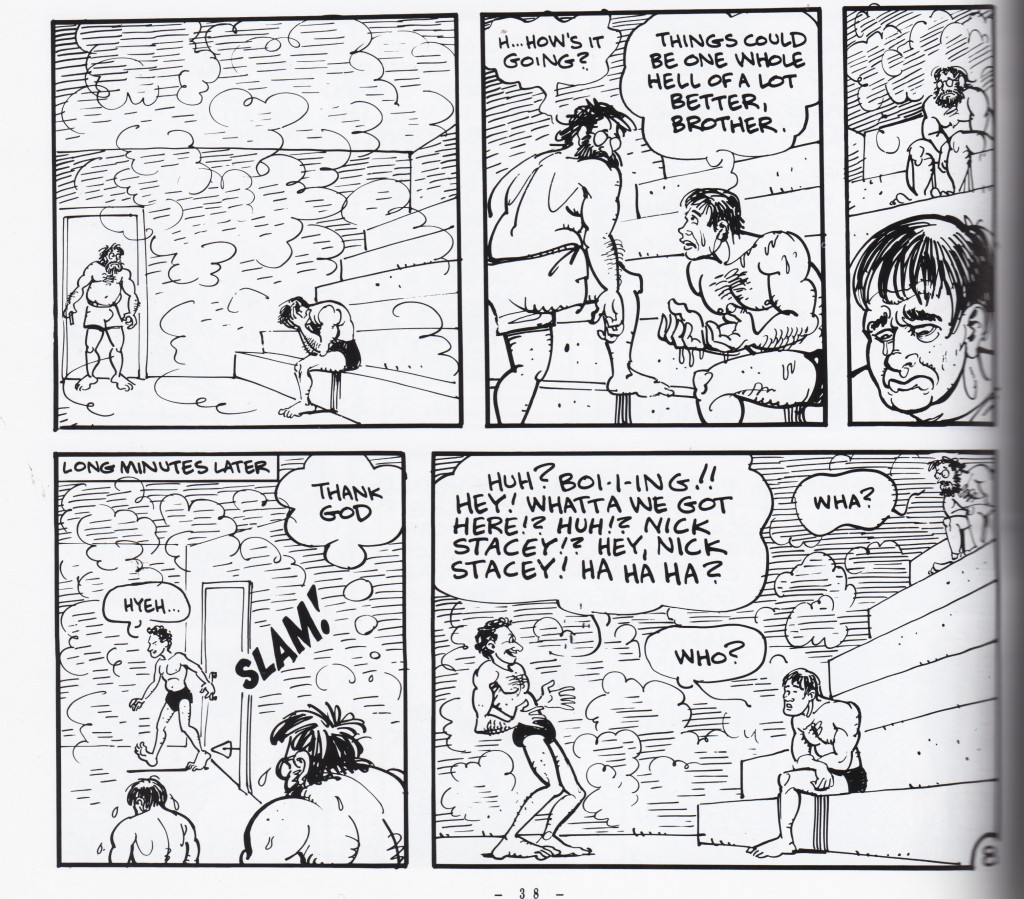

On the May 1st, 1983 strip (below), he adds, “In case you’re interested, a line like that at the end is exactly why I needed Opus in Bloom County. An innocent amidst the insane.”

This is striking, as Bloom County is not lacking in innocent voices. There’s mild-mannered Mike Binkley—while his father conflates his femininity with perversity and cowardice, readers know better, and Binkley’s quiet honesty comes off as rather valiant. There are the forest animals, banding together to elect a presidential candidate for their Meadow Party, and easily perplexed by human kissing. There’s a handicapped doctor who role-plays science fiction fantasy games with said forest animals—his name is Cutter John, which doesn’t seem to be a malpractice joke. There’s the old lady who volunteers to disarm a nuclear warhead using her famous pie recipe. The list goes on. Even Milo Bloom, who in my opinion has become creepy yellow journalist by 1983, has his heart in the right place. And the offensive frat-boy turned lawyer Steve Dallas earns the bemused affection of the cast, mostly because he is harmless. If a certain variation of innocence exists, Berkeley Breathed has created a character to exemplify it.

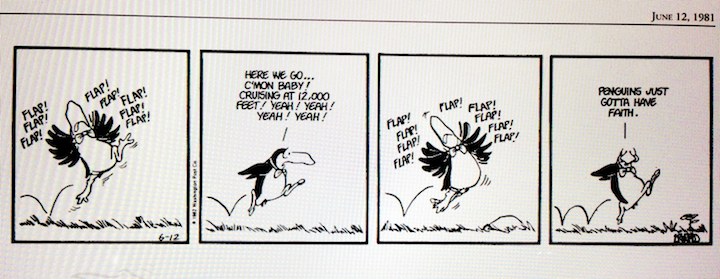

Innocence and insanity are not mutually exclusive either. Innocence is described as a kind of veiled, distorted vision just as often as it is defined as clarity. In this it parallels, and approaches, the definition of madness. No Bloom County character is exempt from delusions, and being made a fool by them. These delusions go hand-in-hand with the rampant ‘fantasy play’– animals pretending to be on Starship Enterprise, children reminiscing about their pretend, exotic love affairs with dead-pan faces– which also interweave with each character’s particular wisdom. Opus is the resident ‘alien’ of Bloom County. He is not tied to the natural ecosystem, like the forest animals, nor did he grow up in the school system, like the kids. Neither was he brought in for a job. He’s a flightless bird. He starts out as Binkley’s pet, and is reinvented as his subtenant. The absurdity of his existence gives him a privileged distance in which to question reality, often because he himself doesn’t understand it. Opus’ perspective remains gentle, optimistic and non-judgmental. The joke is always on him, but life is crazy anyway.

Perhaps what Breathed was trying to say was this: In order to make Bloom County work, he needed a character who was not just innocent, but who pointed out the absurdity of the world in an innocent way, without a trace of domineering snarkiness. Perhaps it was just a coincidence that this focal point arrived in the form of an iconic animal mascot. Or perhaps not. Breathed’s “existentialist penguin” talk aside, I suspect it is actually Opus’ iconicity—his status not as an alien, but as a visual alien—that gives Bloom County its center of gravity. Opus’ body — nose and all — becomes the calling card of Bloom County. Pre-Opus, Bloom County struggled to differentiate itself stylistically from other comics, particularly Doonesbury. Then: enter endearing animal mascot. It’s not the most original act of branding, but it works. Breathed’s breath-holding reverence for Opus betrays an uneasiness that has to tunnel away and re-emerge as Bill the Cat six months later.

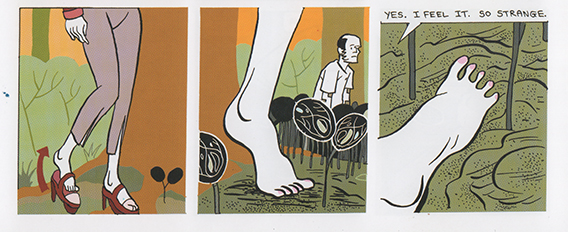

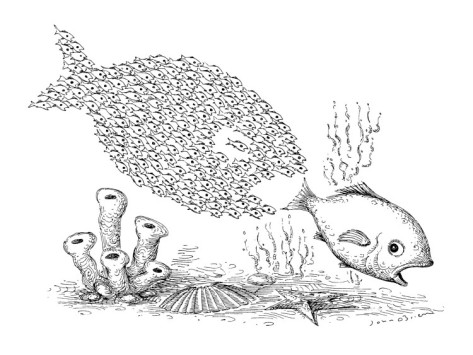

I don’t think that Bloom County needs a mascot for exactly the same reason a sugar cereal, or the Olympics games, or even Garfield needs a mascot. Cartoon animals have nothing to do with breakfast food or professional sports, only with selling them. Garfield is almost nothing but an exercise in branding, (one reason why the experiment Garfield Minus Garfield is so brilliant.) The earliest definitions of comics theory conflate iconicity and storytelling; there is no theory today that does justice to the complex relationship of these two concepts. Opus’ iconicity gives readers a stronger elastic to stretch around and bundle Bloom County’s various parts into something coherent, a Bloom County-ness. He’s the only drawing that feels alive half the time, a slapstick break from all the talking heads. As a mascot, Opus helps Breathed brand the strip. He’s Bloom County’s voice not because his character is the comic’s keystone, but because his image is. And there is a baffling genius to his composition, his pleading eyes and tiny bow tie. As a character, he is just one strand of the large, crazy web of innocents Breathed spins.

_____

The entire Bloom County roundtable is here.