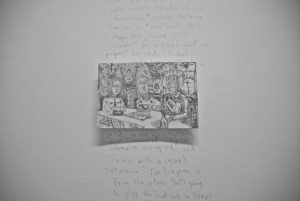

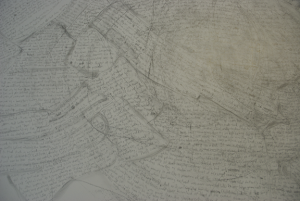

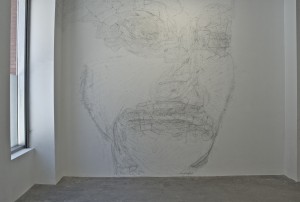

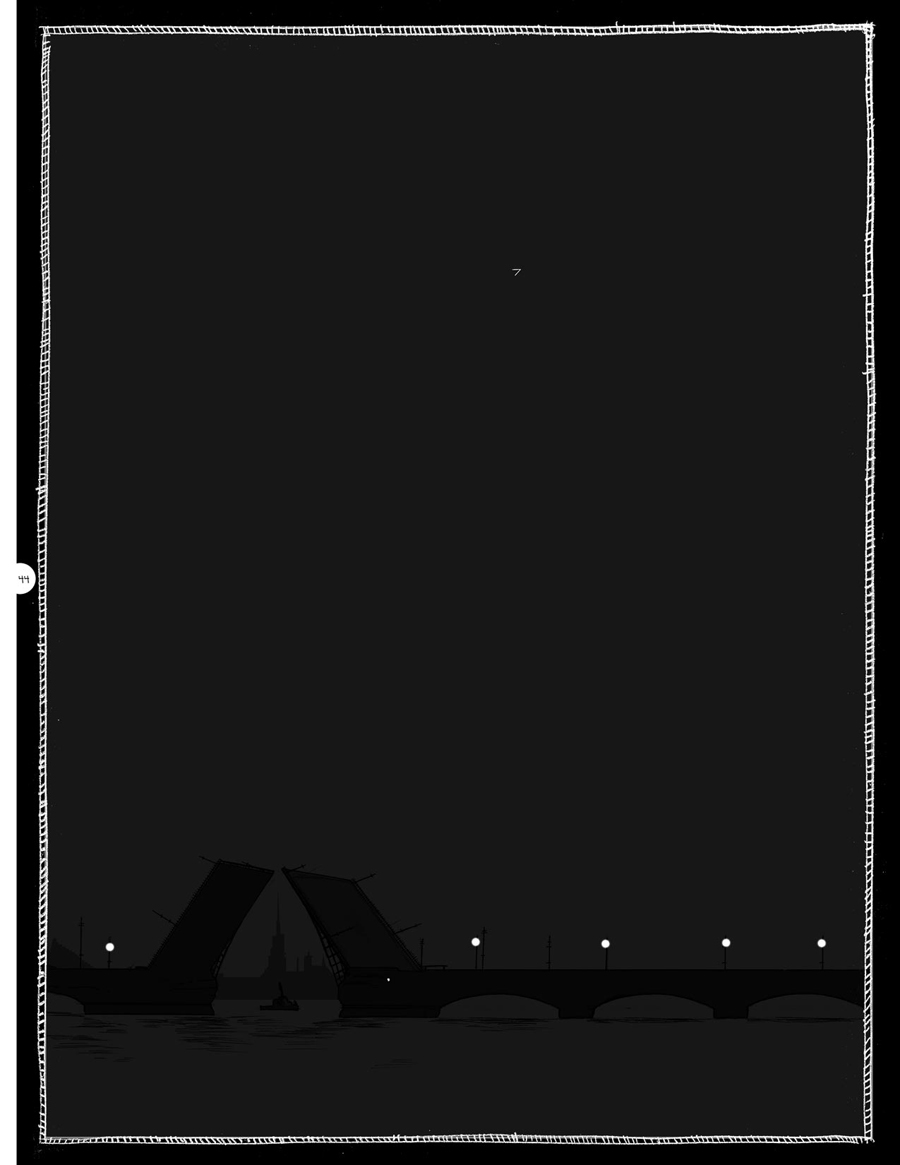

Half of Jeff Gabel’s recent gallery show doesn’t exist anymore. You can probably track down a series of graphite miniatures, but even these were “installed” into the walls with captioning that spilled off or back onto the drawings, now permanently lost. The other two walls beheld a giant, micrographic mural composed of text from the same source, the very out-of-print Salware oder die Magdalena von Bozen by Carl Zuckmayer, (English title The Moons Ride Over.) Chicken-scratched in pencil, the mural developed over the course of the show. By the end of the first day, it was possible to see a face and swirling patches. By the next week there was a fist, and then the lips of a second face appeared. Finally, like a sandpainting, the walls were painted over a day or so after the mural was finished.

The ephemerality of the installation was striking for several reasons. It was spontaneously announced, and it had a very flexible deadline. Half the show was uncollectible, and a charming sense of installation-for-installation’s sake pervaded the space. Additionally, The Very Best of Firmin Graf Salawar dej Stries engages many technological developments, (the usual suspects: mass production and distribution, the collapsing of language and media-specific borders, the rise of visual communication and marketing,) but tells the wrong story about them, and without being nostalgic. The Moon Rides Over was not a book that reached millions and was fragmented through a slew of iterations, even if it was a product of the same market forces. Gabel’s work was an elaboration of a cultural accident, his encounter with a book that failed to be a classic, didn’t make money, and became disposable. This is the forgotten flip side of a culture that is increasingly focused on omnipresent and socialized entertainment. The Very Best of Firmin… evidences that encountering a forgotten paperback and administering your private translations, interpretations and visualizations is as revealing of our cultural climate as going to seeing the new Great Gatsby movie, or The Hunger Games, or reading the originals.

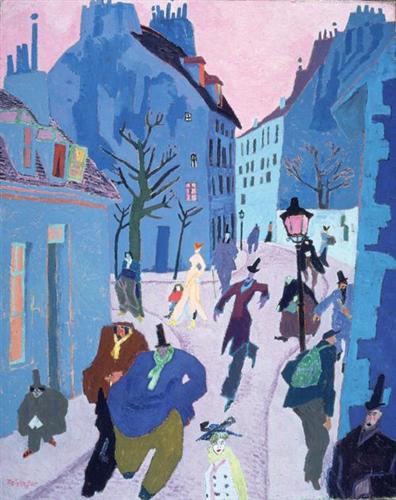

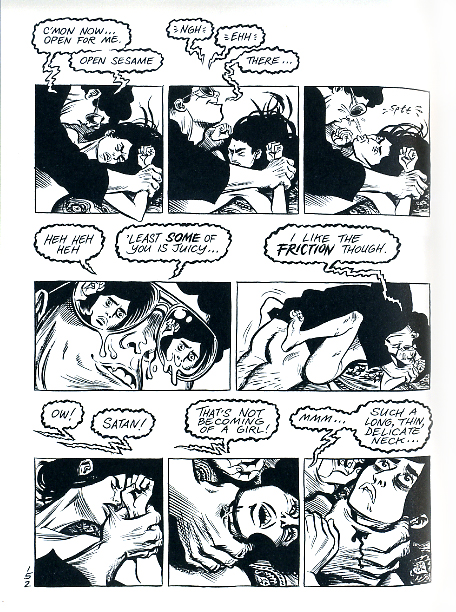

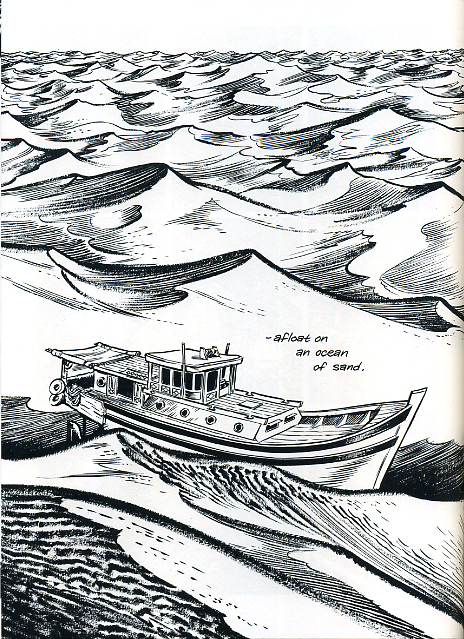

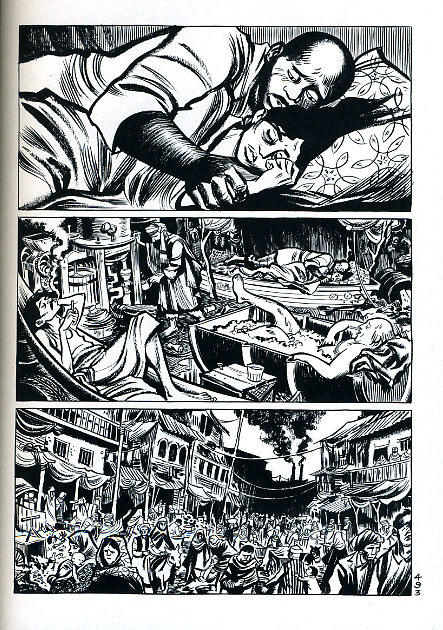

Walking around the show, visitors are surrounded by snippets of stories, but with no clear place to start reading. The most memorable passages share an exaggerated, (and maybe ironic,) visual intensity—a gleaming fish snagged by a woman’s hand, an electric shock, the narrator stranded in the glow of a country inn. Its easy to tell that the story is set in the European Alps, where a group of aristocrats carouse and converse on the grounds of a mansion. There is a good supply of misanthropic monologues about art, sex and war, and from what can be gleaned of Gabel’s show, The Moons Ride Over appears to be a stereotypically modernist novel. But grasping who Firmin, Thomas, Magdalena, Mena and Mario are is difficult, akin to piecing a whole person together from a bit of eavesdropping.

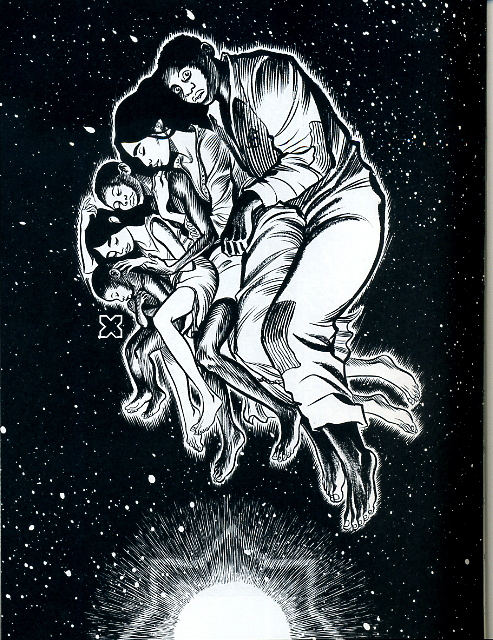

Gabel further muddles visual and literary aspects in his line-work. The miniatures might not be micrographic, but its sometimes hard to tell, as the snatches of graphite resemble his handwriting.

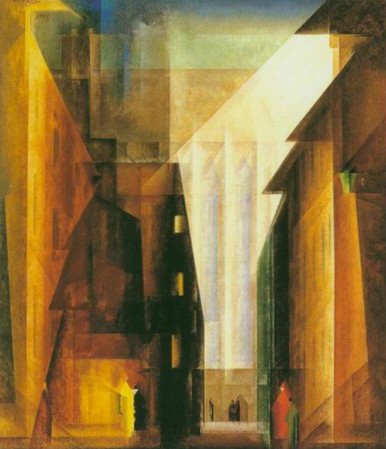

The separation between handwriting and drawing is clearer on the micrographic murals, where the text itself makes up the images. While Gabel’s handwriting is scratchy and casual, the letters are unambiguously drawn and easy to read. I was surprised by this. The doodly, unfinished quality of much of Gabel’s work supports the uncomfortable over-analysis of his biographical work, which better resemble margin notes in a high school library book than developed theorizing. Gabel’s work captures the indulgence and desperation of the eureka moment, where the insight’s implausibility is not grasped until the thought is embarrassingly put to paper. I was impressed to see that Gabel cleanly renders the text while maintaining a adolescent aura. However, the murals lacked the mysterious snail-trail pencil-work of his miniatures, and I felt that the drawings would have benefited from the layering of more text, which would have given them more weight.

If the timing was right, it was possible to catch Gabel at work. I was lucky to run into him the third of four times I visited the show. If I had not asked him, I would never have known that the mural depicted Firmin and the narrator, Thomas. I would never have guessed that the book wasn’t about Firmin in the first place, and that Gabel selected passages that involved him. While I’m reluctant to favor an artist’s interpretation of his work, or treat him like an ambassador to it, Gabel’s presence was built into the show. After I had just walked into the gallery one Saturday, and he asked me for a synonym of “glowing,” I knew there was no going back.

Gabel is a librarian and linguistic auto-didact living in Brooklyn, who taught himself German and stumbled across a copy of the book. On his first read, he was confused by the plot, which involves supernatural (but non-werewolf) moon cycles, incest, and two love interests with the same name. He began to better grasp the book on his second and third time through, when it then began to bloom. While he became increasingly aware of the book’s flaws, he has found its moments too. For example, he’s the first to admit that the prose is unforgivably clunky, but can quickly turn to passages of unassuming and unconscious brilliance, like an enraptured, non-pejorative likening of Firmin’s wife to a cow. But Gabel is honest—he never implies that it was unjust for this book to have been forgotten, and understands that his fascination with it is idiosyncratic and biographical. One brilliant passage doesn’t forgive The Moon Rides Over, but its also worth questioning what is damning it in the first place.

Gabel finished his eighth reading of the book, and has explored it through several projects at this point. I find it touching, maybe wishfully so, to see him working so deeply with such an obscurity. He’s not becoming a Proust scholar, and The Moon Rides Over has no community of fans. But isn’t this the fate of most art out there, that when a work does not become phenomenon, it is treated as a failed attempt? Sometimes you watch a very weird film on TV late at night, or you find a paperback in the trash, or you spend the entire afternoon listening to a iffy local group on Bandcamp. And the point is not that you found something secretly brilliant, and you’ve gained 500 points of social cache. The point is not that you can share this secretly brilliant thing with your friends, or that you scratched something off your bucket list, or that you are studying it anthropologically. There are reasons that the book never became a phenomenon, but in a world with exploding amounts of entertainment and artistic choices, can we justify spending time on something that falls short? Especially as entertainment and art are further and further conflated.

The Very Best of Firmin… is uplifting, but not sentimentally. It’s not that I’d like to see all the terrible books in the world ‘given the attention they truly deserve.’ Gabel’s work suggests that what is meaningful about reading is the way we absorb, process, adapt and translate a story, the way the mind can warp and reorganize it, fixate on certain visuals, forget others, and convert the book into something else.

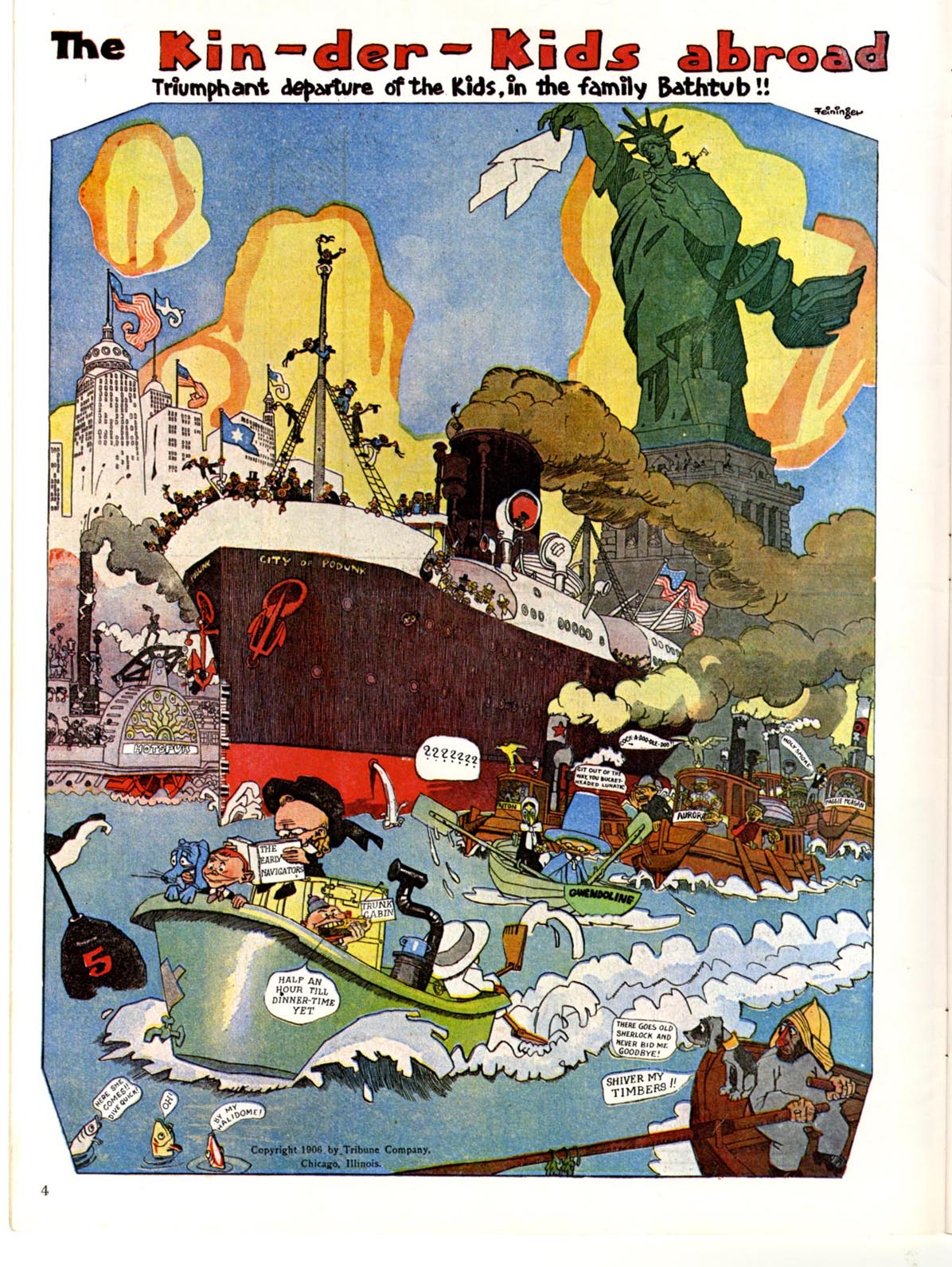

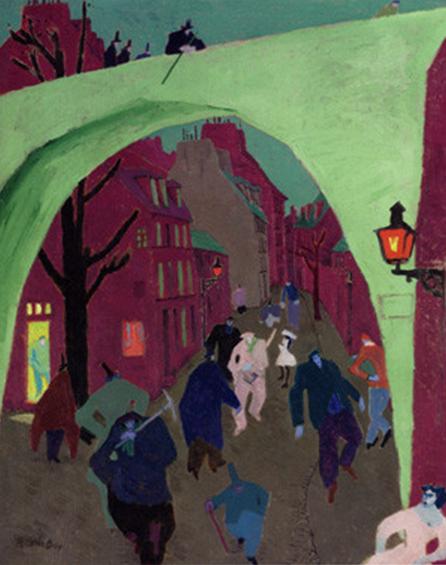

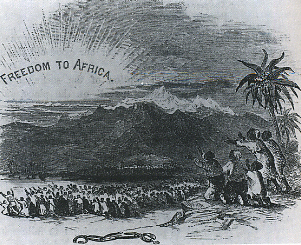

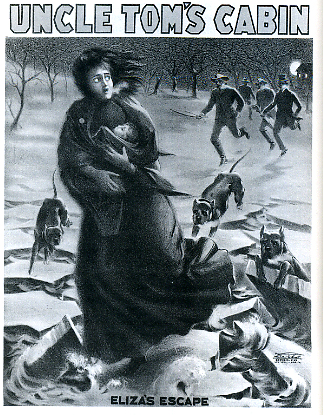

Adaptation is a huge part of this. Linda William’s research with melodramas shows that great stories/franchises have ‘leapt’ from books to stage plays to merchandising since the nineteenth century. In The Very Best of Firmin…, Gabel performs a counter-intuitive translation—where a film version is more accessible than a book, a book is much more accessible than a gallery installation somewhere in the middle of SoHo. Yet his adaptation of The Moons Ride Over into a gallery context is key. Contemporary fine art suffers an enormous schism between canonical mystique and personal practice. The juxtaposition of a mass-produced print and your sister’s watercolor can be found in many households. Gabel’s work skirts the public and the personal, the artifact and the heirloom, genius and the work-only-its-mother-could-love, and makes it hard to tell where one side begins, and the other ends. The show is also a reminder of how much art is not making the jump into digital, and will be doubly lost—it is very difficult to find a copy of The Moons Ride Over, just as it will be a little hard to find a record of this show.

Finally, from the very specific perspective of comics as gallery art, Gabel engages multiple layers of illustration, from the flourishing of the visual in the text, to the micrography and miniatures, to the warp and weft of interpretation. The Very Best of Firmin… didn’t adapt and illustrate The Moons Ride Over as much as explore the psychology of an un-rigorous adaptation and illustration. Perhaps ‘interpretation,’ ‘translation,’ ‘adaptation’ and ‘illustration’ are just facets of the same mental mechanism at play whenever we read something and pass it on. And while human exchange favors certain works over others, great meaning can be taken from a poor book, simply from spending enough time with it.

Images courtesy of the artist and Spencer Brownstone Gallery

Wikipedia page for Jeff Gabel