No Touching At All, Kou Yoneda, October 2010, June

My attention is scattered. There are so many shiny things, you know, and all the boring and/or dreary things, and also the bus, which certainly isn’t shiny but also isn’t boring or exactly dreary, because there are always weird things going on, on the bus, and also I can read my Kindle. I don’t read yaoi on the bus because I’m not completely shameless. It gets tight on the bus, and not everybody wants to see that ho shit before work. What was I talking about? Oh, right. So many things, so little time. I pretty much never reread anything, no matter how much I like it, because there’s this towering stack of unread manga (actually several towering stacks of unread manga), to say nothing of the towering stacks of unread books (both physical and virtual). I read it and move on – baby, baby, I’ve got to ramble. But when I finished this manga, and went right back to the beginning and started over.

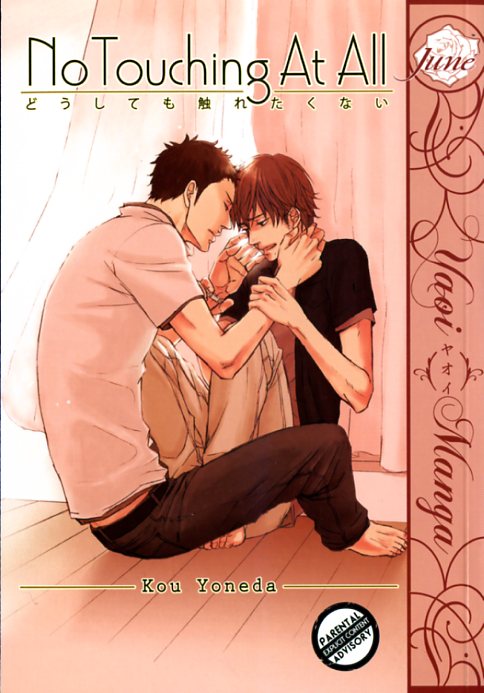

I wasn’t all that excited about No Touching At All based on reading the description on the back cover. “On his very first day at a brand-new job, shy Shima is trapped in the elevator with a hungover mess of a guy… who turns out to be his boss!” If you read yaoi, you now know how this book is going to work. Shima is a shy, nice guy, and also a bottom, and he’s going to fall in love with some drunk, disgusting asshole who’s also his boss. Drama will ensure, but their love will triumph. Yuck. Usually, I’d rather not. Life is too short to saddle yourself with some drunk, disgusting asshole, even for the hour or so it takes to read a comic book. But the front cover – well, the front cover is different.

The story and art in this manga have a gentle quietness to them, a stillness that lets the uncomplicated but poignant details play out and reverberate in a way I found affecting. On the cover, the smaller guy (yes, that would be Shima) is so nicely rendered, folded up into himself, wound up tight, eyes downcast, but holding on to the other man tight, desperation palpable. That’s a lot for one illustration, and nicely drawn, too. The other man is the drunk, the boss, Togawa. Ignore the fact that his back and torso make nonsense of perspective, space, and possibly time. And that something truly unfortunate is going on with his right foot, which looks like a depilated bear paw. Actually, his entire right leg is perplexing. But never mind. The way he’s holding but not quite holding Shima is beautiful. He’s in love, and I am hooked.

The story isn’t icky, either. One might think this comment is damning the thing with faint praise, but not so. I think of these manga as being a bit like noh plays. (I’ll bet you weren’t expecting that.) There’s a finite number of traditional themes. (Also, all the roles are played by men.) (This isn’t meant to be an air-tight comparison, by the way.) There’s a number of stock themes, and the creators change the details (ideally) from manga to manga in ways that might not look exactly original to all comers. They don’t need to be. We don’t necessarily want them to be. A certain amount of the enjoyment comes from exploring all the nuances of your chosen scenario. Fluffy, weepy little fruit loop getting dominated by “rakish” asshole of a boss is not my chosen scenario, thus my initial concern. To be clear, it wasn’t that I was afraid the book wouldn’t be original – I have no expectations that it would be original. I just wanted it to tweak the same old stories well. “Well” can, to a certain degree, be defined as “in ways I like.”

Shima isn’t a fluffy, weepy little fruit loop, though. (Well, yes, maybe he is weepy. It plays all right, though – he has his reasons. I don’t have a generalized problem with male characters crying, but there’s a style of yaoi that has the uke carrying on like John Boehner.) Shima’s character is well-imagined; he feels real, and most of what we know about him is told through the drawing. We see him staring stoically at the elevator doors as he first meets Togawa, who is still drunk at 9 a.m and about to vomit. (“He stinks,” Shima thinks to himself as he stares.)

We see him sitting quietly at his desk as he listens intently for information about Togawa, never giving anything away. Shima is quiet and contained. Cautious. When he finally pushes Togawa against a wall and kisses him – this is after they’ve had sex, so it’s an ownership move rather than a “confessing my love” move – it’s believably surprising. And moving. We feel how far Shima has come to allow himself to do this, and how desperate he is.

Shima has the requisite sad backstory, but Togawa’s sad tale of woe is grim in a serious and complete way. And he’s a nice guy, it turns out. Easygoing and considerate. The requisite three-quarters-of-the-way-through-the-book breakup is Shima’s fault, a combination of the usual contrived misunderstanding – probably a seven-ish on the one-to-ten scale of authenticity and plausibility, as these things go – and an odd but perhaps believable reaction to Togawa’s unfortunate background. The contrived misunderstanding is often a problem – it doesn’t have to be utterly believable, since it’s more of a plot device than an integral part of the story, but if it isn’t believable enough, you don’t get the payoff of relief and catharsis or whatever. In this case, the cause of the problem isn’t entirely solid, but what carries it is, as usual, Shima’s small reactions.

The pacing often feels off at this point in the story. After the long, detail-filled lead-in, lovingly chronicling the falling for each other phase, the near-breakup and getting back together part tends to get short shrift, as if we’re three quarters of the way through the run and we have to wrap this up. I often start losing track of plot points right about here, and that happened with this book, too. But in this case, it isn’t that I’m annoyed about suddenly not being sure what the story is about any more; it’s that I feel like I’ve missed out on some good stuff.

Rushed though the resolution may be, it is romantic. The characters’ movements and reactions to the plot contrivances ring true. Full pay-off for my inner sap (you don’t have to scratch too hard to find it).