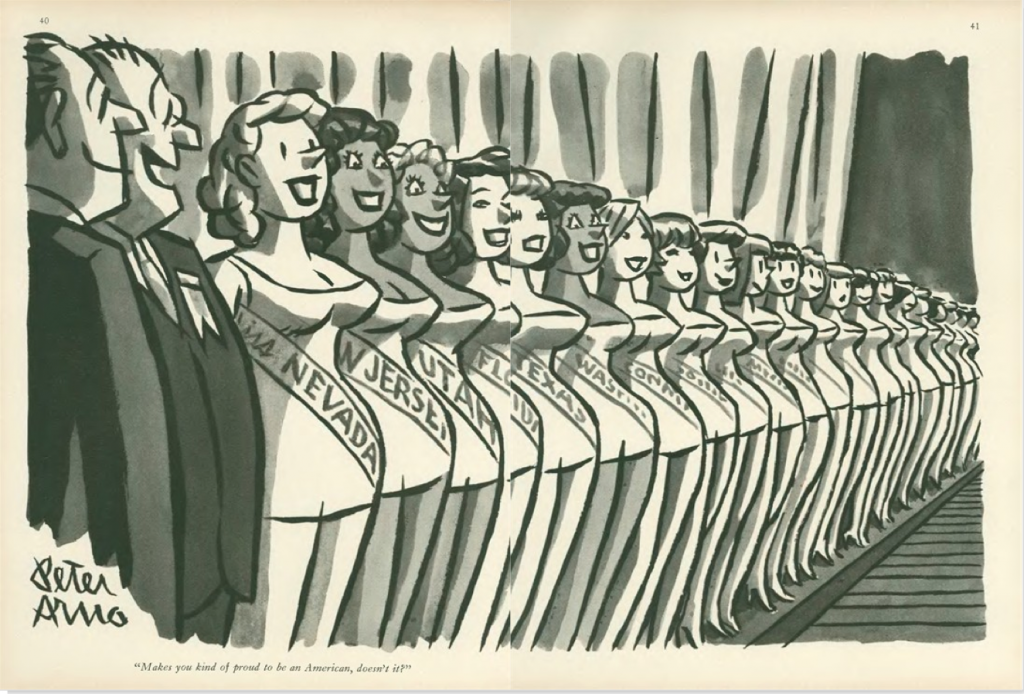

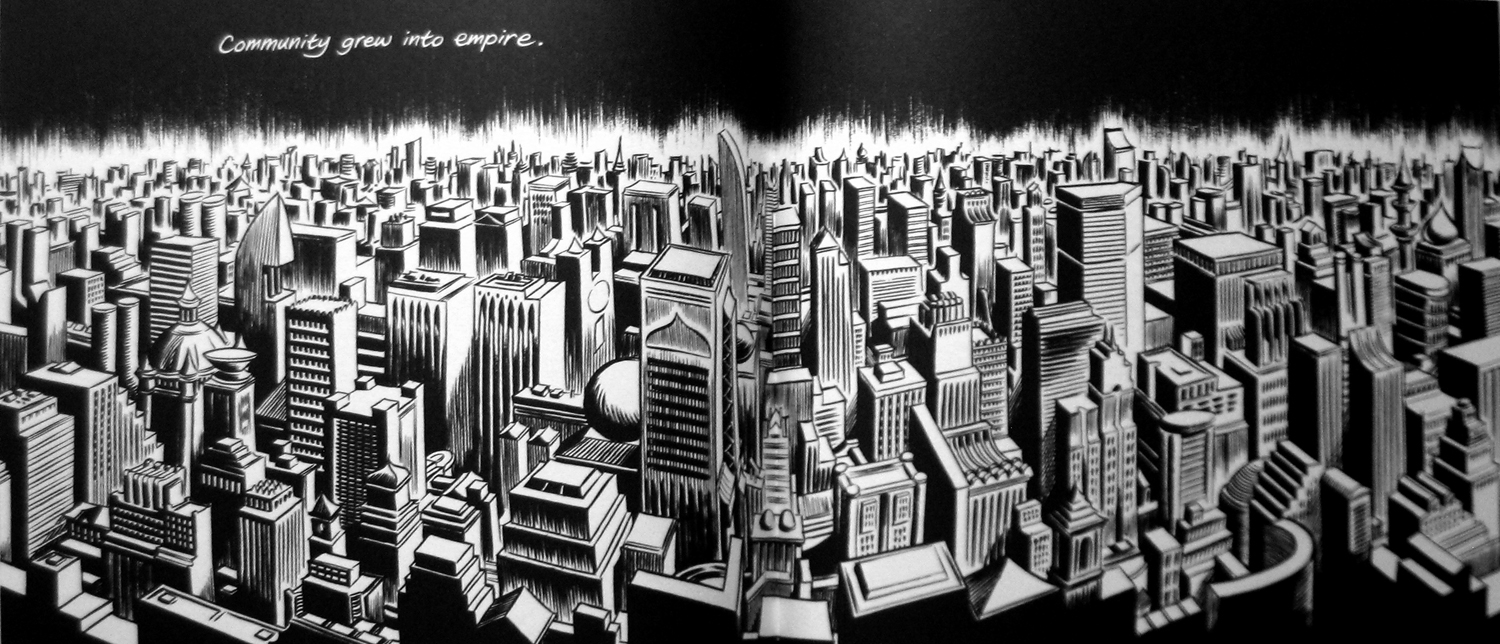

Peter Arno, “Makes you kind of proud to be an American, doesn’t it?”, September 10, 1960

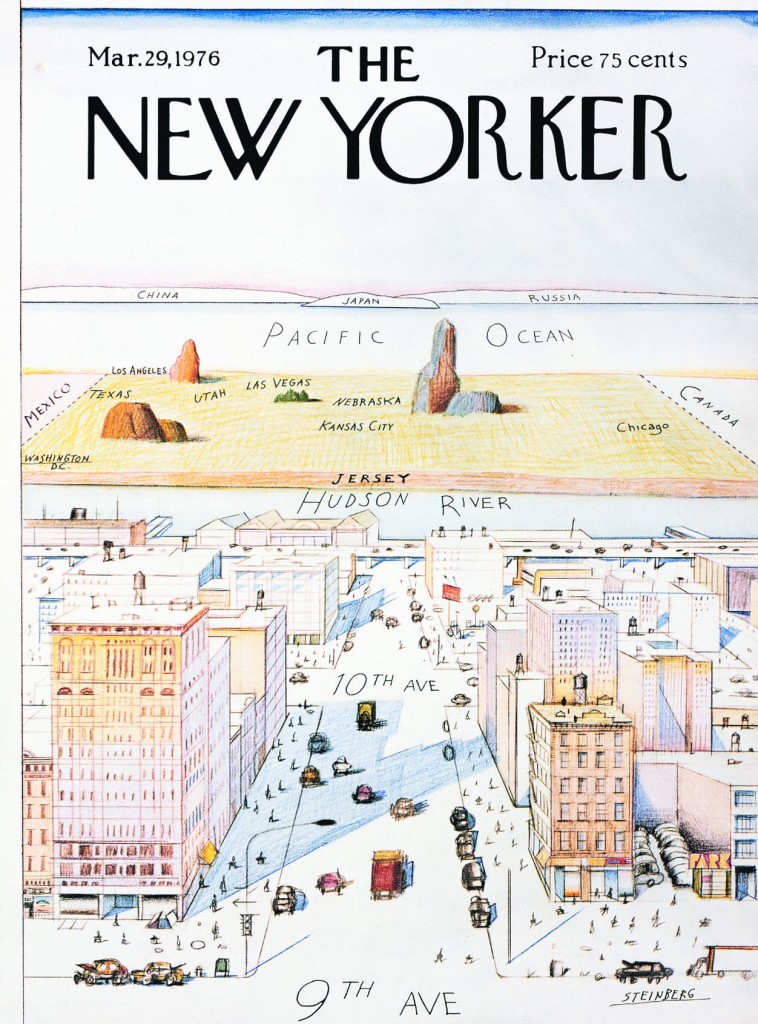

I

The standard line on The New Yorker’s cartoons is that they are the first thing most readers turn to when they get their hands on a new issue. Well, I don’t. I actively try to avoid looking at them, difficult as it is. Peppered through articles of serious journalism, strong criticism, and pieces of often very good fiction, they are meant, I suppose, to induce some kind of alchemical understanding of what it is to be a New Yorker, or — failing that — a New Yorker reader. To me, and I suspect quite a few others, they remain obnoxious non-sequiturs, like tired notch-notch, wink-wink routines insistently dropped into an otherwise lively family conversation by your borderline senile uncle.

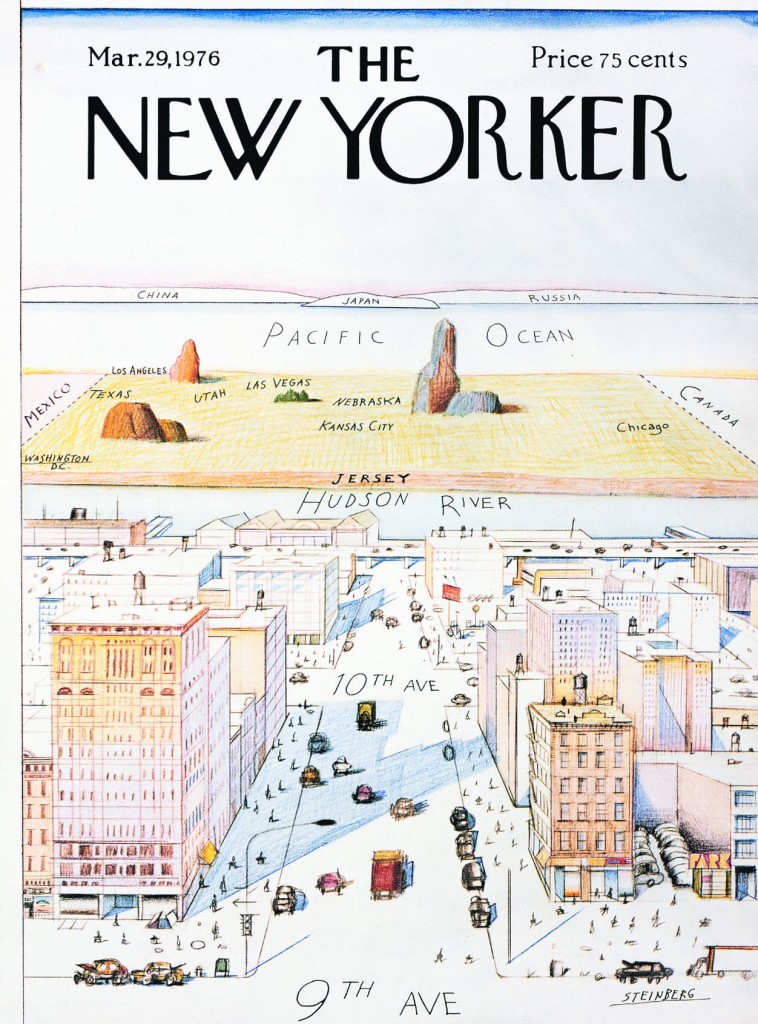

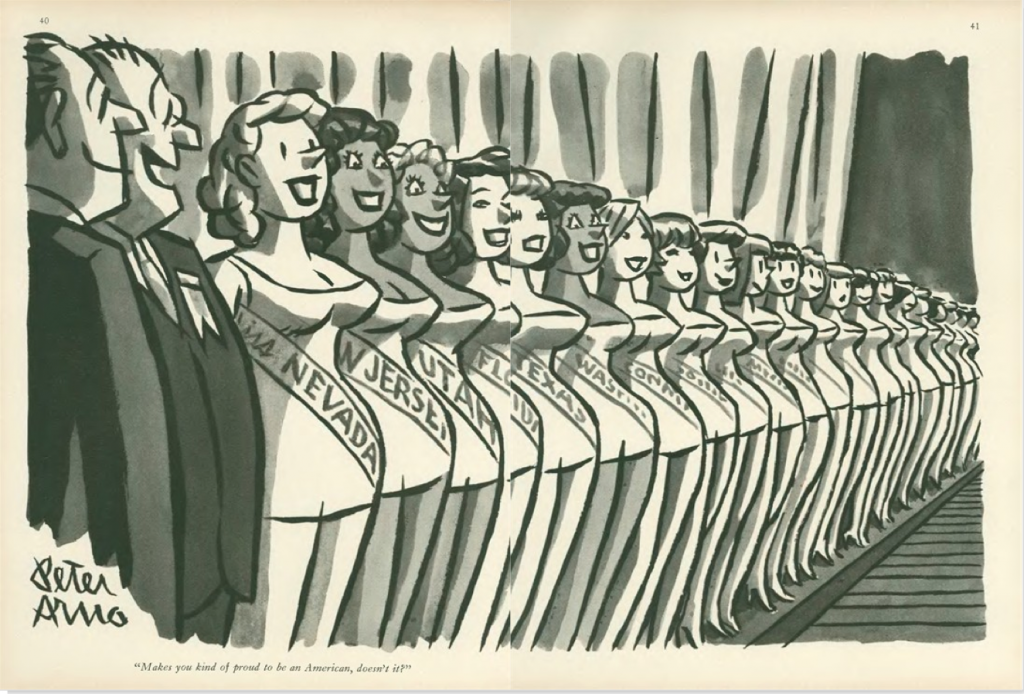

The other oft-repeated line about the New Yorker cartoons is that a lot of people ‘just don’t get them,’ with the frequent corollary that this is part of their point, and once you realize it, you feel ‘in’ with those in an authentic New York state of mind, I suppose — you know, those whose worldview Saul Steinberg summed up so incisively in what remains arguably the most famous New Yorker cover of all time.

Saul Steinberg, cover, March 29, 1976

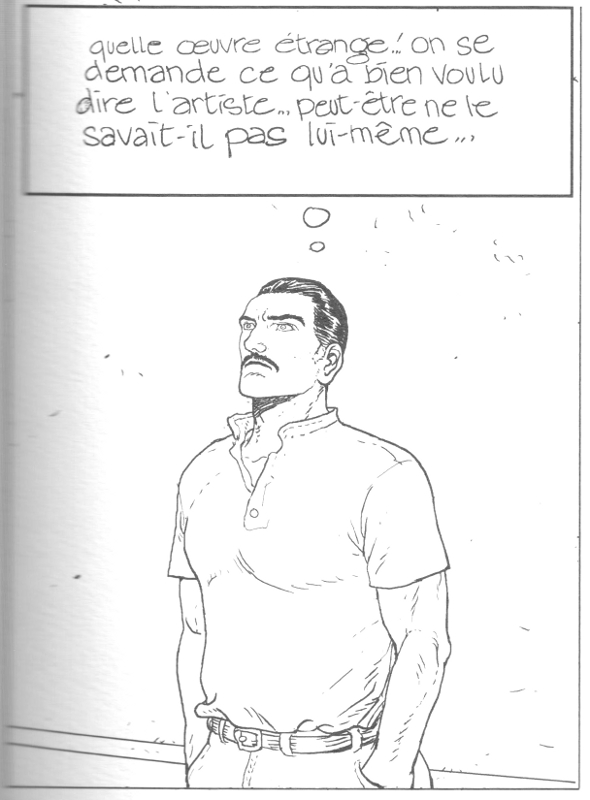

Thing is, if you actually review a substantial selection of cartoons from the magazine’s octogenarian history, the vast majority of them are totally straightforward. You understand the joke. No Mystery. Only in the last decade-and-a-half or so has editorial showed a preference for a certain brand of light absurdity that at times borders on the impenetrable. Nothing wrong with absurd humor, but the problem in this case is that one of the main strengths of cartooning, clarity, is sacrificed in a vain bid for ingenuity.

From this week’s issue: Robert Mankoff, October 8, 2012

This more or less corresponds to the period in which hack cartoonist Robert Mankoff has served as cartoon editor. He has been a hugely successful manager of his part of the New Yorker brand, merchandizing the cartoons through the online Condé Nast Cartoon Bank to the tune of millions of dollars a year, as well as editing the monumental Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker (2004), which bundled all 68,647 cartoons thitherto published in the magazine on two CDs. Bonus info: he has had over 800 cartoons published in the magazine.

Mankoff furthermore is the instigator of the popular New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest. And far be it from me to suggest we deny people their fun, but the concept is revealing of his editorial philosophy, where the visuals become so generic that they accommodate just about any joke. Absurd or not, the naughts have been the nadir of New Yorker cartoons in every respect, from idea to execution. More than ever, one suspects that the notion that they harbor some elusive brilliance available only to the in-crowd really just euphemistically expresses a general puzzlement about how unfunny they are. As in, ‘can they really be that bad?’

More from this week: Tom Cheney, October 8, 2012

We are, after all, talking about the Holy Grail of American cartooning. The one publication countless cartoonists would hack off their non-drawing arm to be published in. The New Yorker, somehow, has managed to convince a wide, generally discerning and highly cultivated readership that their cartoons represent the acme.

Try as I may, I have been unable to assimilate this View from Ninth Avenue. Reading through several thousand of the cartoons assembled by Mankoff in his 2004 book, I cram to understand it. From the very beginning in 1925, the New Yorker cartoons as a rule have been unambitious, unimpressive, and unfunny. Not to mention frequently sexist. As a platform for cartooning, the magazine has (with a few exceptions, to be addressed presently) been a deadening force at the heart of the art form, smothering the field in bourgeois mediocrity.

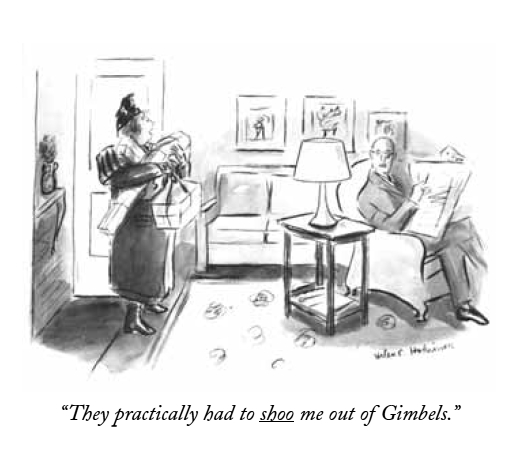

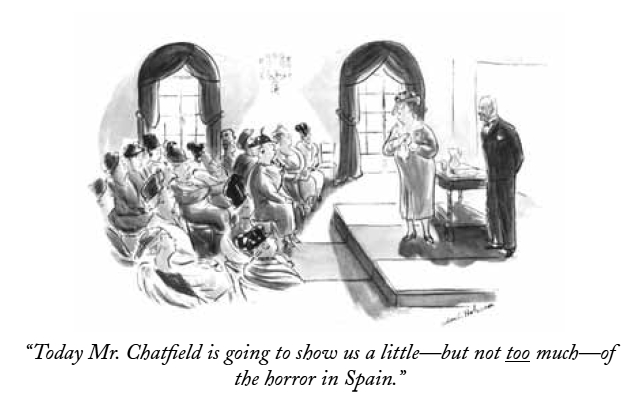

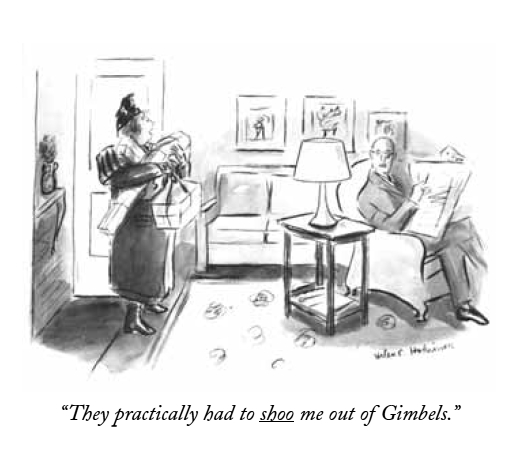

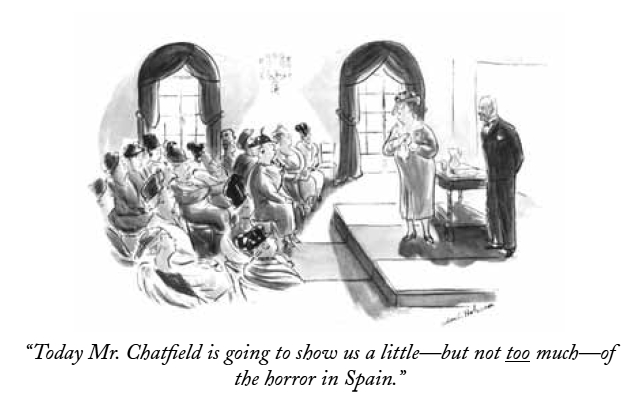

Helen Hokinson, December 11, 1937

In a 1937 article in the

Partisan Review,

The New Yorker’s

bête noire of the time Dwight McDonald — later a significant contributor to the magazine — criticized the cartoons for their

“Jovian aloofness from the common struggle”, identifying

“…something inhuman in [their]

deliberate cultivation of the trivial.” This critique was part and parcel of McDonald’s, and the

Partisan Review’s, ongoing criticism of the

The New Yorker more generally. McDonald concomitantly described the typical writer for the magazine as having

“given up the struggle to make sense out of a world which daily grows more complicated. His stock of data is strictly limited to the inconsequential.”

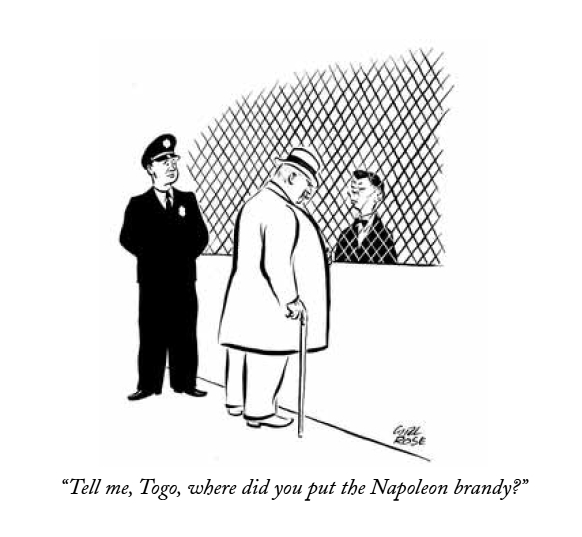

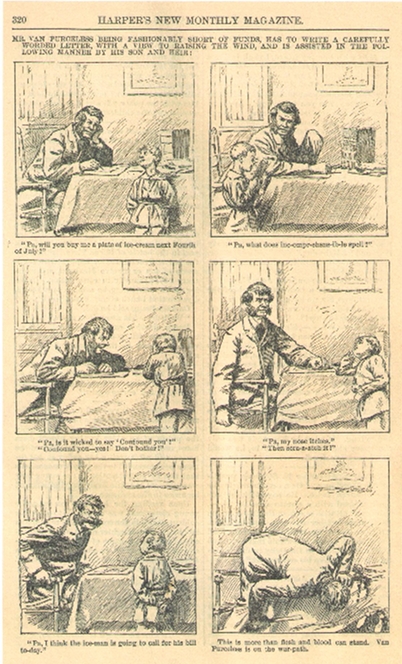

William Galbraith Crawford, October 13, 1934

This is not the place to enter into the long and complex history of

The New Yorker and its critics. Suffice it to say that any institution, cultural or otherwise, that achieves this kind of success and influence will be met with criticism — and indeed McDonald’s words are echoed in those of many a critic of the magazine since. But whatever the problems of ‘New Yorker fiction’ as a phenomenon, of the blind spots exhibited by the magazine’s critics, or of its at times timid or problematic treatment of important political issues — most recently perhaps the 2003 invasion of Iraq — it is undeniably one of the publications of record in all three areas.

In other words, McDonald’s critique, however accurate it might be in diagnosing a fundamental aspect of founder Harold Ross’ vision, does not render justice to the ambition and quality of the magazine, then or now. Where it does ring true, however, is in its characterization of the cartoons, then and now.

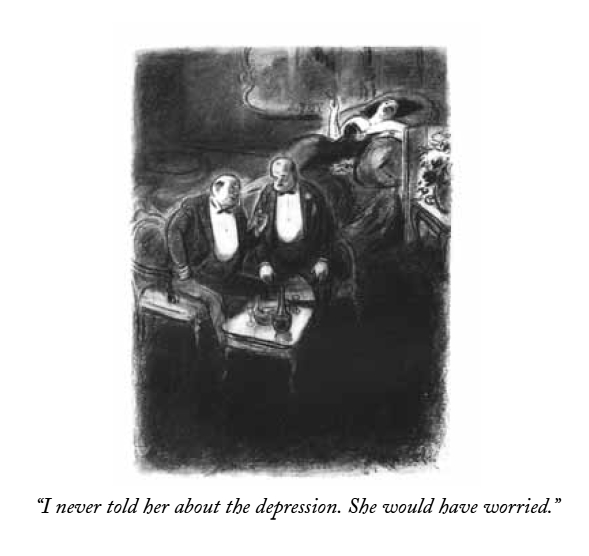

Reaction shot: Rea Irvin, December 20, 1941

Reading the introductions to each decade of

The New Yorker’s publication history in Mankoff’s

Complete Cartoons, each written by a different author connected with the magazine — from Roger Angell and John Updike to Lillian Ross and Calvin Trillin — one is struck by their apologetic tone. They are forced to acknowledge the obvious: that

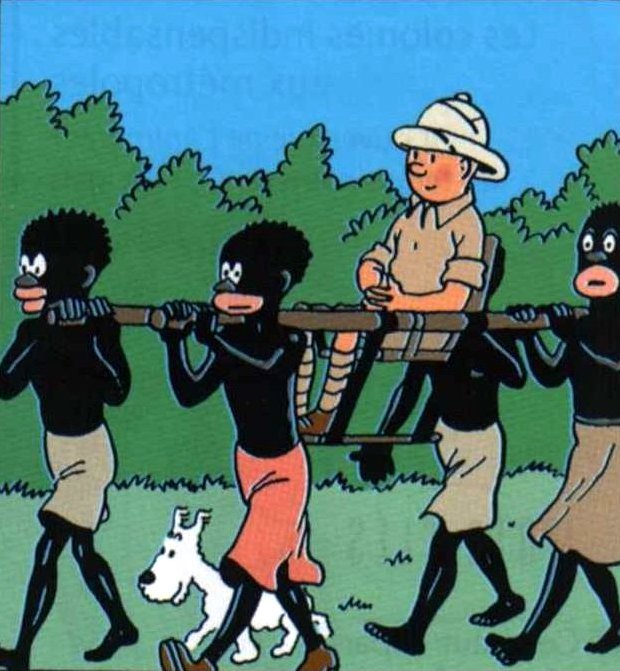

The New Yorker’s cartoonists almost never managed to comment intelligently — or indeed at all — on the important events of their time, be it the Great Depression or the Second World War, the civil rights movement or Vietnam.

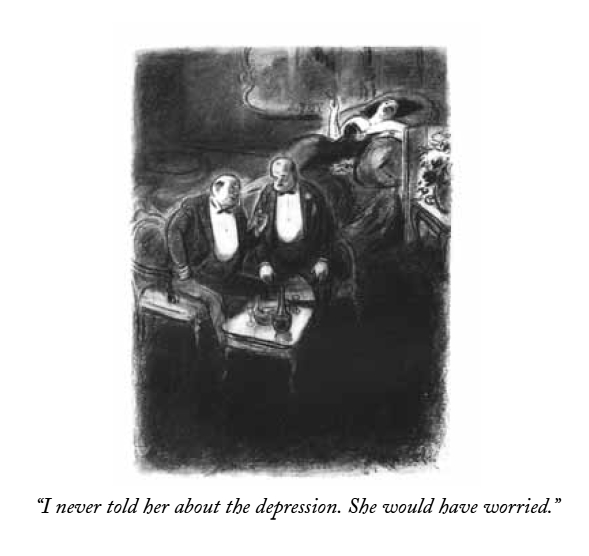

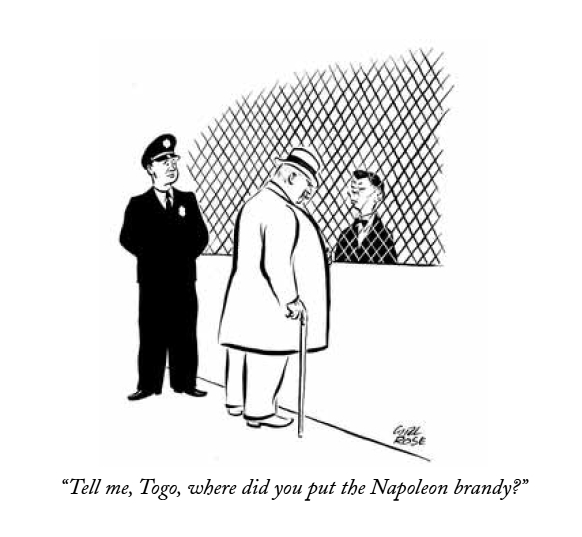

An exception to the rule: Carl Rose, December 20, 1941

This was all in keeping with Ross’ sensible if not unproblematic vision that

The New Yorker would

“not be iconoclastic”, marketing it as he did to

“intelligent and discriminating men and women who appreciate fine things and can afford them.” While it would be a fair question to ask why the magazine has shied away from political or otherwise editorializing cartoons, especially when their other content is much less hands-off on such matters, this in itself is not the problem. The point is that choosing gags as your calling does not let you off the hook. Major national and world events belong as much to the social sphere (the domain of gag cartoons), as it does the political or economical.

The New Yorker, however, was content with serving up endless iterations of two guys in a bar, desert islands, and bosses and their secretaries — a dull superfluity of safe inanity.

Warren Miller, April 6, 1968

III

The gag cartoon is a difficult discipline. The trick, of course, is to make the reader laugh. The joke’s the thing. And there is no accounting for humor, which makes accessing your own in its purest form the noblest avenue of expression for the cartoonist. Not to mention the funniest. It is not so much that there are not a fair amount of fairly funny jokes in The New Yorker, but rather that they are almost invariably of the generic variety, with cartoonists content to act as warm bodies on the mic stand, interchangeable and disposable. Too few of them present a truly original, unexpected, idiosyncratic, intelligent, or imaginative point of view, and judging from just how consistent the magazine has been in this regard, it seems editorial has rewarded them for thinking inside the box.

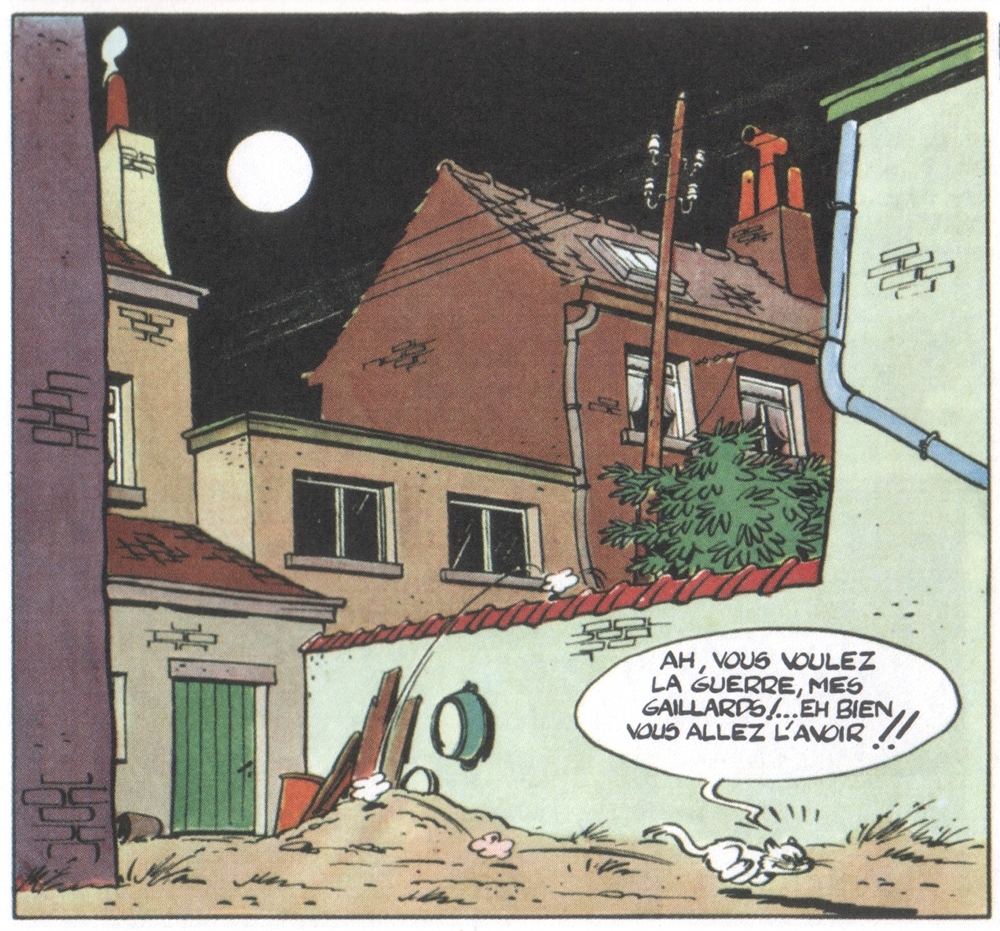

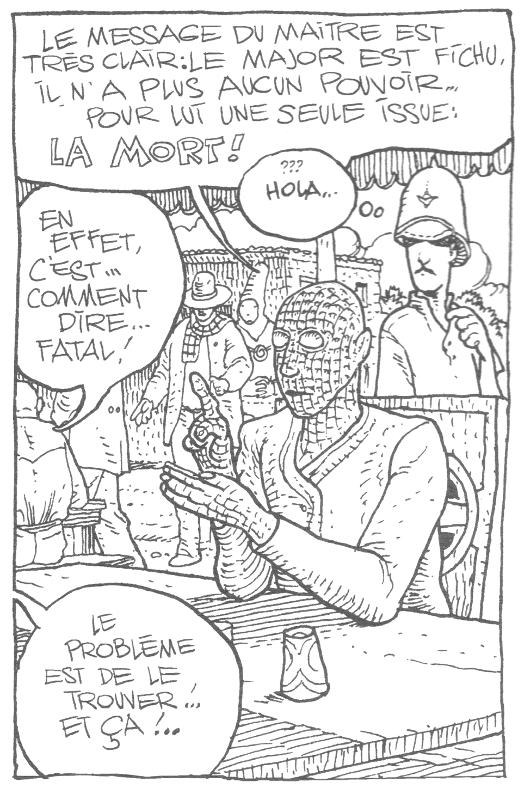

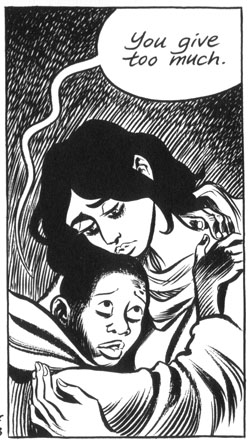

Peter Arno, April 12, 1930

Let us forego the banal swill that bulks up the bibliography and focus on some of the canonized artists; the best the magazine has had to offer, according to public opinion. First there is Peter Arno, the quintessential dandy cartoonist, a kind of real-life Eustace Tilley, cuffs stained with india ink.

No doubt, Arno is one of the great visual stylists of American cartooning, and arguably the most effortless major graphic contributor to the magazine. His cartoons are master classes in composition and narrative, at times carrying an almost abstract beauty in their distribution of forms, light, and shade. Yet, his visual characterization, while extremely precise and frequently funny, is invariably trite, serving up conservative stereotypes spritzing the safe clichés of the masculine bourgeoisie — from Martini jokes to silver fox slickers ogling chorus girls. Very little of Baudelaire’s flâneur remains in his and his various gag writers’ myopic, self-sufficient perspective.

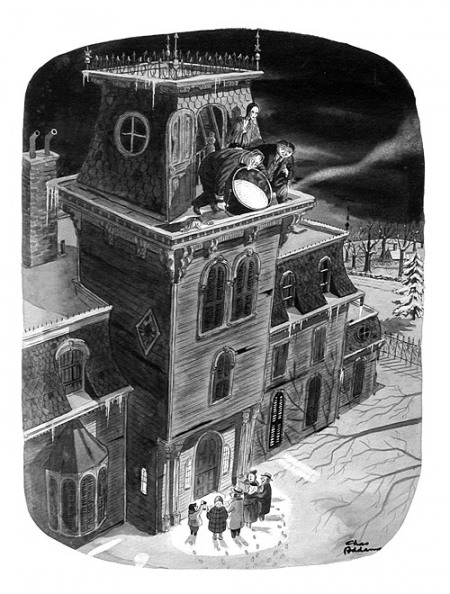

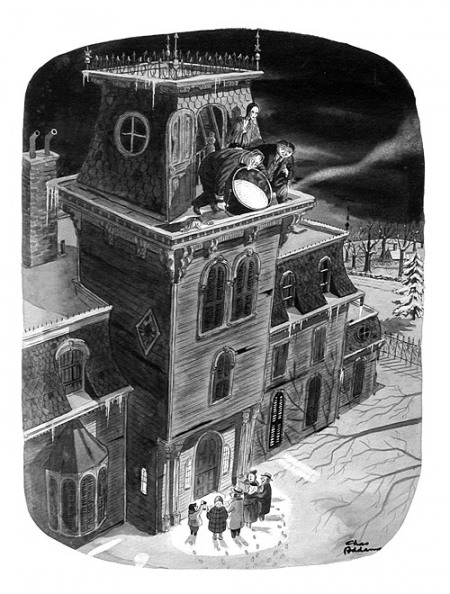

Charles Addams, December 21, 1946

Another icon is Charles Addams, possessed of a genuine yen for the absurd yet ultimately toiling it in service of warm reassurance. His earlier cartoons boast some inspired ideas and occasionally reach toward the surreally unsettling, but by the time he had established the Addams Family, those lovable munsters in their plush Halloween mansion, he started descending irrevocably into comfy family camp. Worst is the utter lack of visual ambition — one plump Addams character pretty much substitutes for another, any signs of individuality listlessly muddied up in drab wash.

Helen Hokinson shows some self-awareness: May 1, 1937

Helen Hokinson suffers from similar problems of visual realization. Drawing her characters small and indistinct, it is frequently hard to glean anything significant, relating to the gag or otherwise, from their facial expression or body language. A pity, because her wit (or that of her gag writers) is sharp, if limited in scope — lots of rotund society ladies, lots of hat, dress and jewelry jokes. Her irony cuts a little deeper than that of most of her peers, but dissipates with a dispiriting ‘aw shucks’ fizzle.

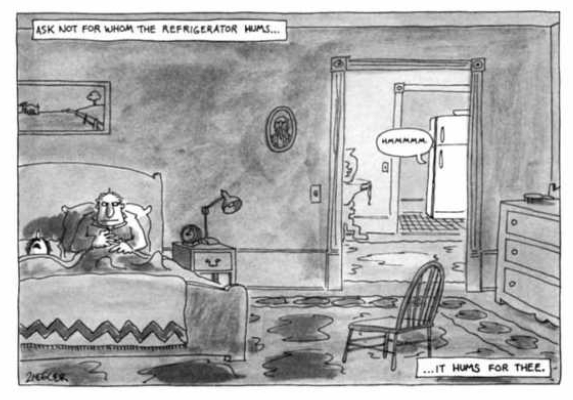

Jack Ziegler, November 24, 1980

Of later comers, Jack Ziegler is one of the most prominent, I suppose both for his versatility and consistency in terms of joke content, but also, surely, because he is somehow quintessential. Beyond the shoddiness of his rendering—more complex of course, but essentially no different from the arid cartooning of a Scott Adams — he lacks a core: emotional, personal, what have you. To him a joke is just a joke, and he can be relied upon to makes us laugh and forget, issue after issue.

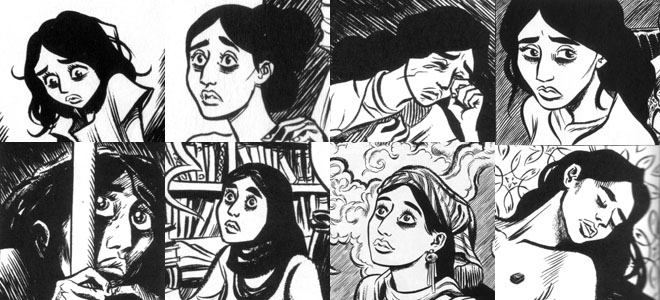

Roz Chast, December 7, 1998

Then there’s Roz Chast,

The New Yorker’s current cartoon fig leaf for artistic respectability. She is to be commended for introducing into the magazine a kind of poetic whimsy previously unknown, and for deprioritizing the punchline in favor of more ineffable humors. Unlike most of her colleagues, she actually has a personal voice, but it is never particularly revealing: a step beyond the imaginative dazzle, it is cute and cosy, keeping anything difficult at arm’s length.

This complacent tone is apparent more than anywhere else in the lazy drawing, which remains unimproved after more than thirty years. The telephone doodle charm only goes so far, because the small, overcrowded, inarticulately composed, and sluggishly washed drawings rarely contribute more than a very general — if persistent — sense of caffeinated giddiness, ending up placeholders for ideas worthy of a more articulate cartoonist. It’s like watching Ted Rall impersonating Lynda Barry.

Bruce Erik Kaplan, September 17, 2012

Next to Chast, Bruce Eric Kaplan is the seeming exception that proves the rule that current

New Yorker cartoonists all lack personality. His graphic style is his big draw: everything is drawn as if by etch-a-sketch, centering on a supposedly existential emptiness. It is indeed spectacular in the dull context of the magazine, an easy standout, but it’s a shtick: the cartoons are interchangeable, their links to individual jokes tenuous at best, and the general sense of alienation is unmodulated to fit the content. The same idea executed ad nauseam.

III

I could go on, but the point should be clear. These are highly overrated cartoonists, elevated by their august platform. And keep in mind that they are the wheat to the vastly more abundant chaff. One might argue that gag cartooning is simply not suited to the kind of artistic expression lacking in the pages of The New Yorker, that I’m setting the bar too high here, but besides questioning the wisdom of focusing so one-sidedly on gags at the expense of other forms of cartooning, you could point to Mad Magazine — a publication whose cultural impact, however different, is commensurate — as a much more reliable source of quality humor cartooning, despite its own faults. The critically overlooked Don Martin easily trumps any of the above-mentioned for originality and plain laughs. As do a number of cartoonists working in similar formats never — or rarely — published in The New Yorker, from H. M. Bateman and Virgil Partch to Basil Wolverton and Gary Larson.

William Steig, March 24, 1986

In a way, however, the most damning factor is that

The New Yorker harbored a few cartoonists whose example — if it had been internalized instead of merely idolized by editorial — would surely have helped shape a truly innovative cartoon platform. One is William Steig, a cartoonist of fertile imagination, a well-honed instinct for portraying the human animal, and — as he matured — a nervous line crackling with personality. One might argue, however, that he did his best work elsewhere, primarily in children’s books.

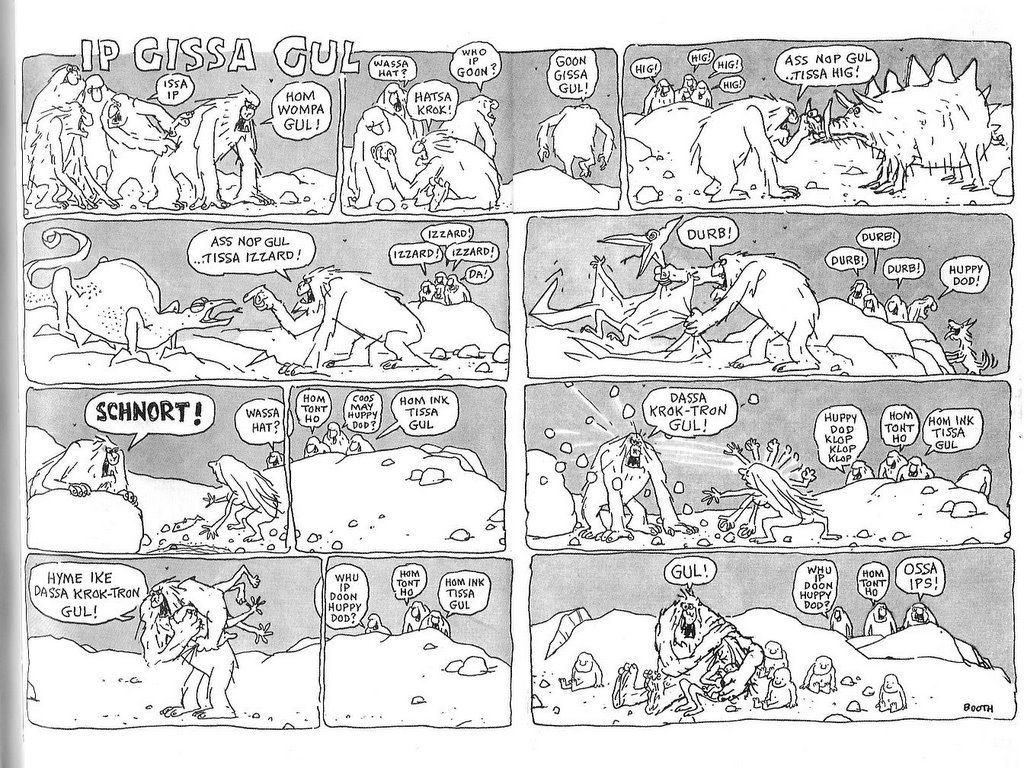

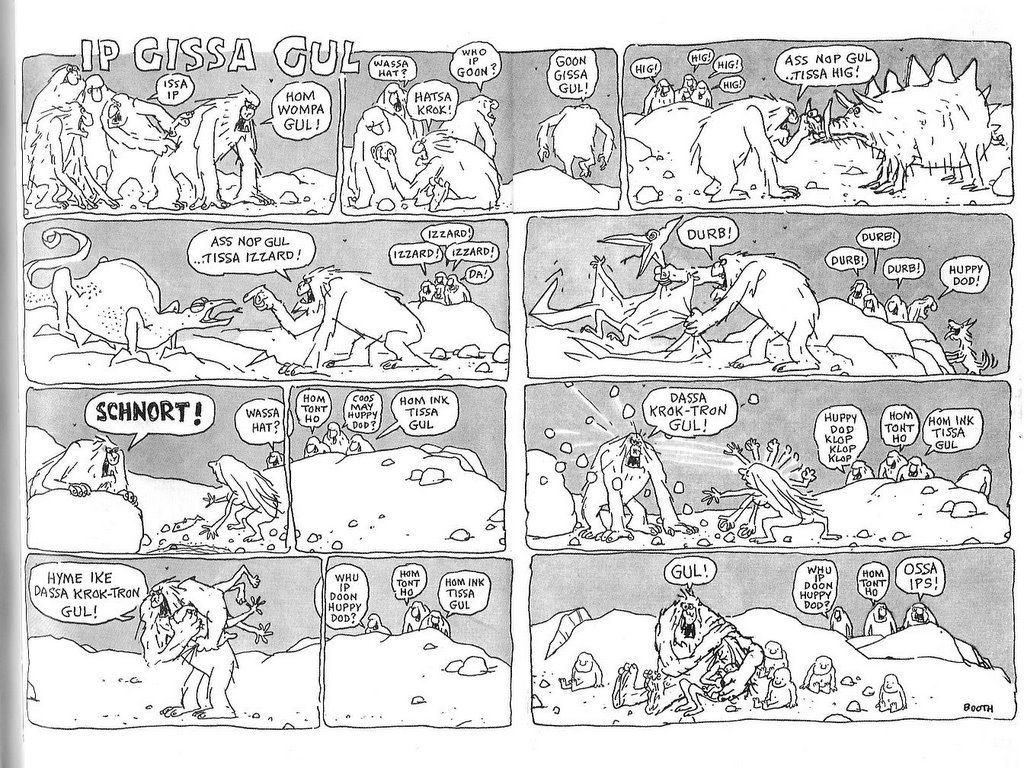

George Booth at his best with the early “Ip Gissa Gul”, January 20, 1975

A bright spot in the dim latter half of the William Shawn years was George Booth. Although not the most gifted gag writer, his anarchic humor as manifested in his ratty line, and trademark rat-like dogs, is an unexpected delight in the murk that is any given issue’s cartoon selection. At times, he comes off not a little unhinged, not unlike the aforementioned Don Martin. More of his kind would have been a help, but not enough in itself.

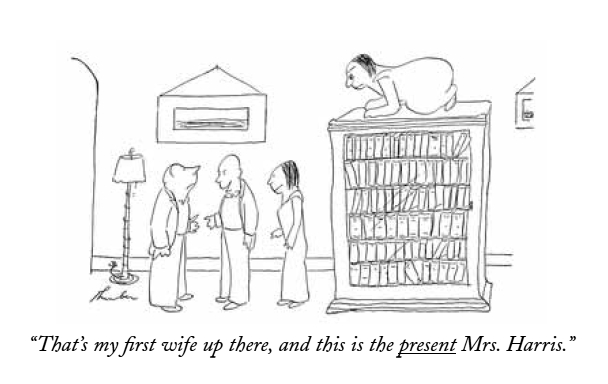

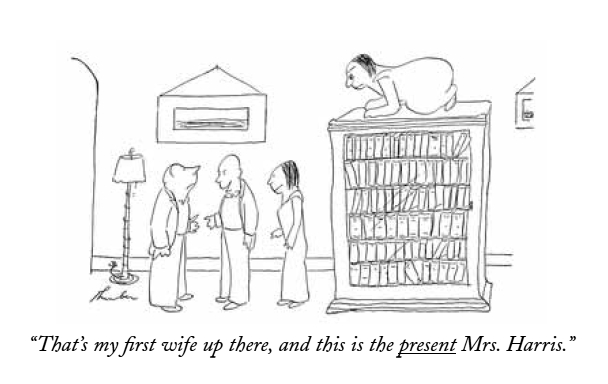

James Thurber, March 16, 1935

The true paragons — of course, I suppose — are James Thurber and Saul Steinberg, however. The half-blind Thurber was a natural cartoonist, possessed of a genuinely original vision that included as acute an eye for human behavior as any of his fully-sighted peers, condensed on the paper in sprightly notation. His treatment of his main theme, gender, may initially seem a little banal until one notices the disturbing irrational undertones pushing at the edges — the ex-wife lurking on top of the bookcase, the seal behind the bed, the sudden fencer’s head-lop. Thurber’s is a cold world, and the gleam in his live eye is humor.

The strange thing is how little his approach came to shape The New Yorker’s cartoons. Of course, few cartoonists can be expected to be as original, but he remains an example of what can happen if one admits and nurtures the personal sensibilities of a gifted cartoonist. Although this was initially Thurber’s good friend E. B. White’s doing, Ross clearly grew to appreciate Thurber, who became one of the magazine’s graphic constituents (and literally part of the architecture by way of his graffiti, a piece of which has been transposed into an oblique corner of the current offices in the Condé Nast building). It is hard not to see it as an editorial failure that his example wasn’t followed.

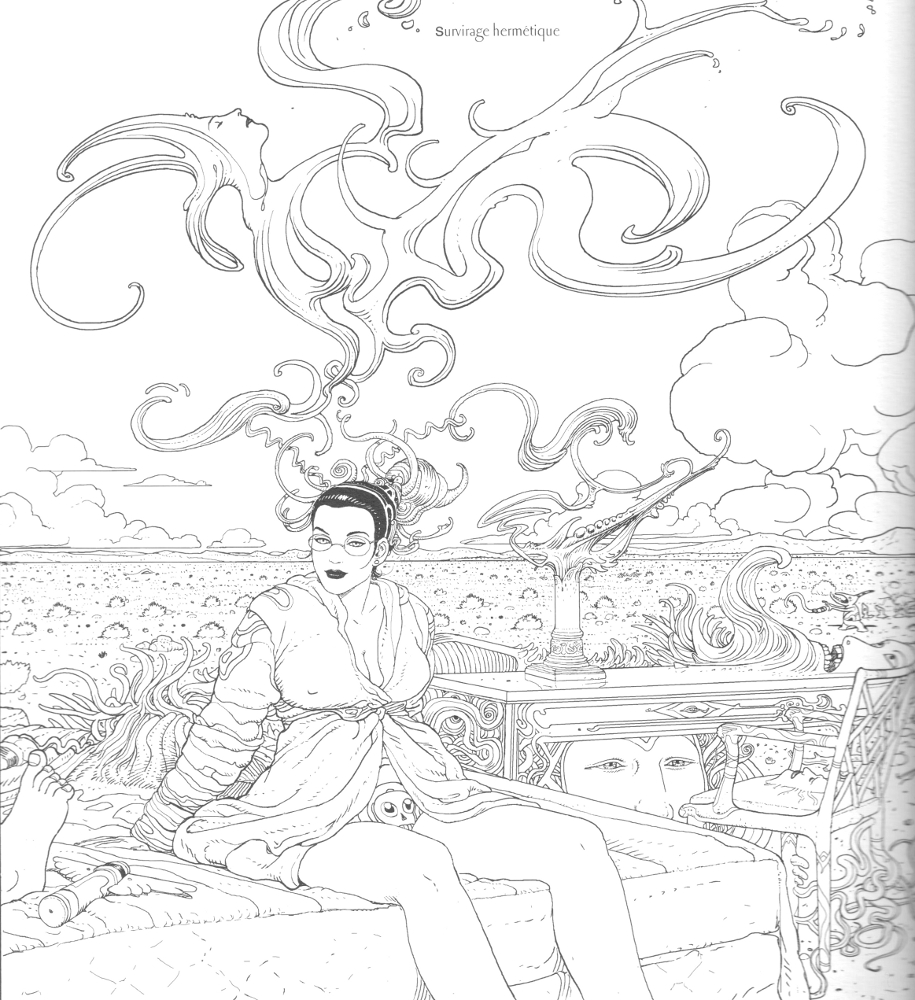

Saul Steinberg, November 25, 1961

Except with Steinberg, one of the century’s great cartoonists. Although just as unique, he became much more central to the magazine’s graphic identity than Thurber, and his influence on it remains much more pervasive, if in all the wrong ways. A cartoonist of brilliant facility and mind, he unassertively situated himself in the continuum of modernist art, but with a distinctively post-modern sensibility, Steinberg was the quintessential meta-cartoonist. He elevated the discussion of what cartooning is and, by consequence, the significance of

The New Yorker to the art form.

Now, I must confess to some reservation vis-à-vis Steinberg. It’s easy to appreciate his cleverness and I do love his line, but I largely agree with Tom Lubbock’s critique that there is something too controlled, too detached, too safe about his cartooning, which is obviously witty and intelligent, but neither really funny nor really troubling. This takes us back to the central problem with The New Yorker’s cartoon tradition and how Steinberg validates its ethos, despite his outsize talent: New Yorker cartoons are often witty, if rarely intelligent; they are occasionally funny, but never troubling. They perpetuate an escapist bourgeois utopia, detached, controlled and safe.

What’s frustrating is that it could have been different. The New Yorker could have exerted the same level of ambitions on the part of their cartoons as they developed with regard to journalism, criticism, and fiction. Ross’ project to endow the magazine with a strong graphic identity was smart and it worked, not the least because of the often excellent illustrations and the famous covers. But the cartoons remain a monument to mediocrity, a would-be canonical example of wasted opportunity, were it not so bafflingly extolled as a high watermark. As it stands, I don’t doubt that The New Yorker would have been better off without them, and in my darker moods I feel as if the art form as a whole would have too.

P. C. Vey from this week’s issue, October 8, 2012

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.