I have not yet been to India. Unlike Belgium, China, or Egypt — who’s respective comics’ scenes I feel comfortable writing about at length predominately because I’ve lived in those places with the time afforded to trace how the Ninth Art relates to their national histories — I am coming at the Indian landscape of comics with little more than the information provided by Internet strangers. I also know a paltry amount about the socio-economic issues historical and currently facing Indian people (save what is to be learned from a New Yorker article or two). To recap: I know who Nehru was the and the jackets he wore, I understand the concept of caste, I enjoy the writing of Amartya Sen, I’ve watched Krrish, and I weirdly had dinner with Salman Rushdie one time. As one might imagine, this admittedly makes me a very poor candidate to write at length about Indian Comics and history with any sort of authoritative voice. However, my lack of India credentials does make me the ideal candidate to consume the graphic novels recently released by New Delhi based publisher Navayana.

Navayana — translation: “New Vehicle” — was founded by S. Anand and Ravikumar with the explicit interest of being, “India’s first and only publishing house to exclusively focus on the issue of caste from an anticaste perspective.” To that measure they have released an impressively diverse catalogue of books since 2003 addressing the issues of caste in India through critical essays, poetry collections, nonfiction novels, and, most recently, graphic novels. Today I will look at the two politically charged English-language graphic novels Navayana has published in the last year under the creative direction of S. Anand: Bhimayana (2011) and A Gardener in the Wasteland (2012). In particular, their relative successes at addressing issues of caste dating back to the 18th century for a global comics audience in the 21st century.

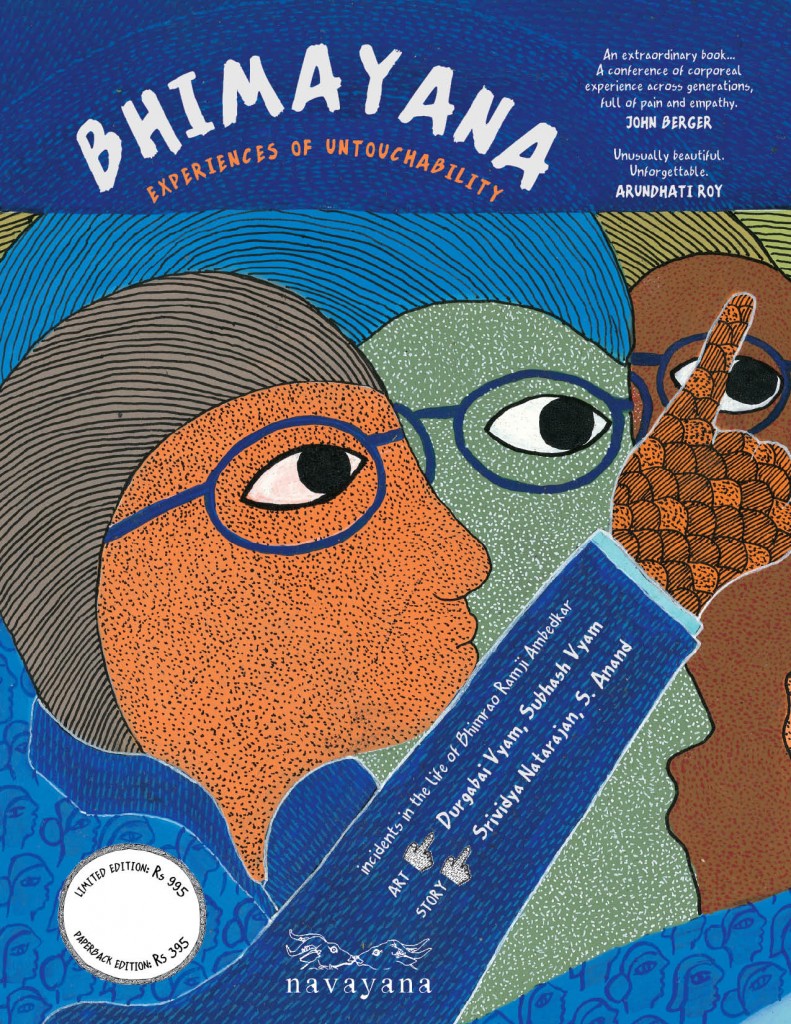

Before readers get into the innards of Bhimayana: Incidents in the life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, they must first process a helping of expectations-building praise from an impressive cadre of writers. Scattered along the jacket sleeve are pull quotes from John Berger (who also pens a fawning Forward), Arundhati Roy, and Joe Sacco. “Extraordinary” writes Berger, “Unusually beautiful” writes Roy, “Distinctive” writes Sacco, and from the flip of the first page these accolades have a context that makes sense. The story itself, as the title indicates, weaves together snapshots from the life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956) — one of India’s fiercest opponents of the caste system who is best known for crafting the language of India’s human rights constitution. Bhimayana assumes the reader has no knowledge of Ambedkar at the onset and proceeds to provide an education of the events that shaped his life and how he in turn shaped the lives of many in India.

Born as a Dalit (the lowest of castes known as untouchables), Ambedkar faced a great deal of hardship in his youth before a generous Maharaja Sayaji Rao-sponsored fellowship afforded him the opportunity to study abroad at Columbia University and the London School of Economics. After returning to India with a Western education (problematic, I know!), Ambedkar devoted his life to an anticaste agenda which he realized through impassioned speeches, books, law briefs, a controversial series of debates with Ghandi, and a latter day conversion to Buddhism. But while the particulars of Ambedkar’s story are as inspirational as any other of his few civil rights leader contemporaries, they are not what makes Bhimayana ground-breaking. In most hands a story like this could come out as a boring and by-the-numbers graphic biography, but thankfully those are not the hands of married artists’ Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam, who bring Ambedkar’s story to graphic novel.

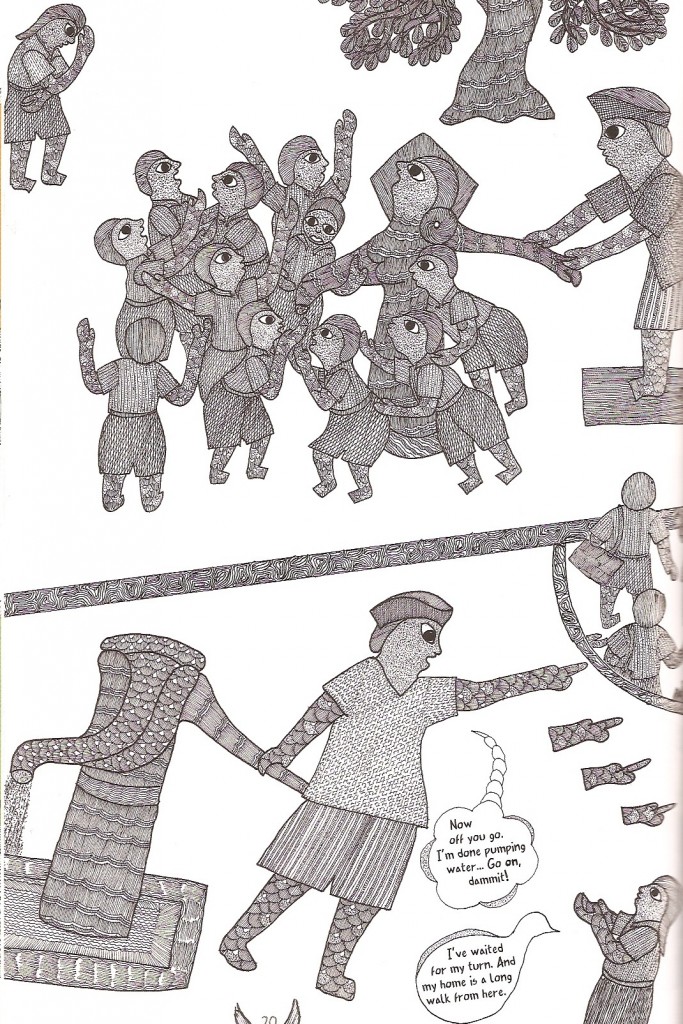

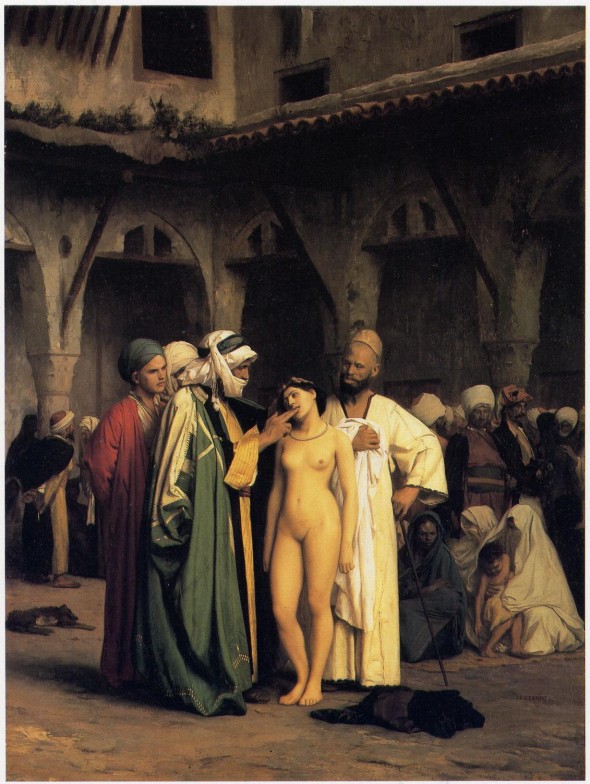

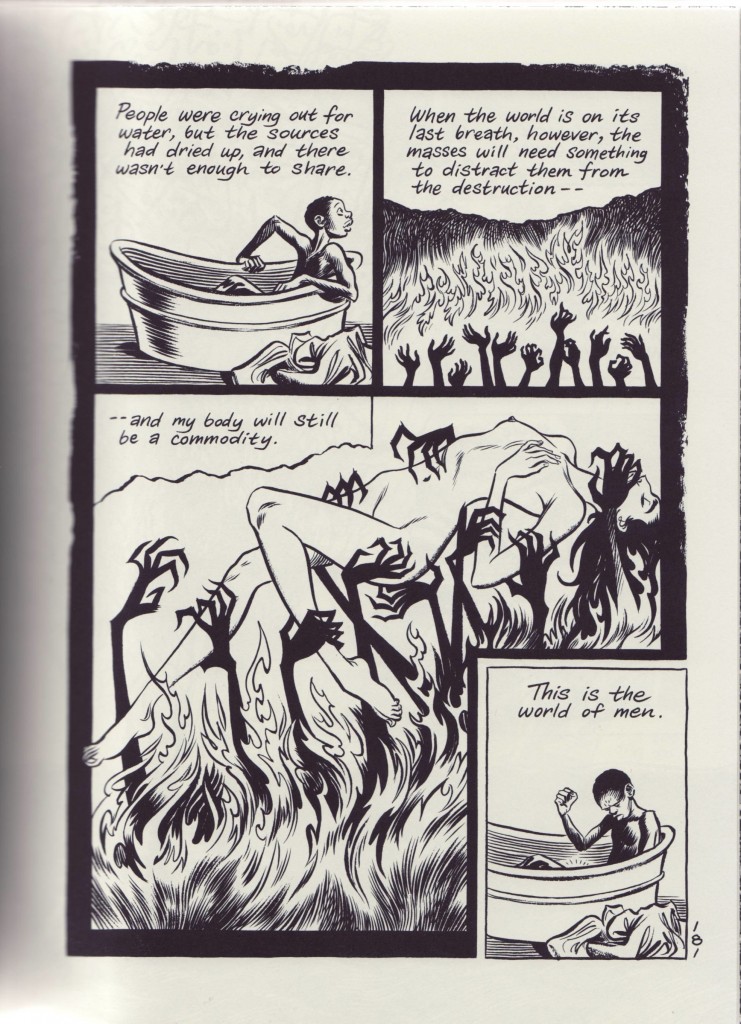

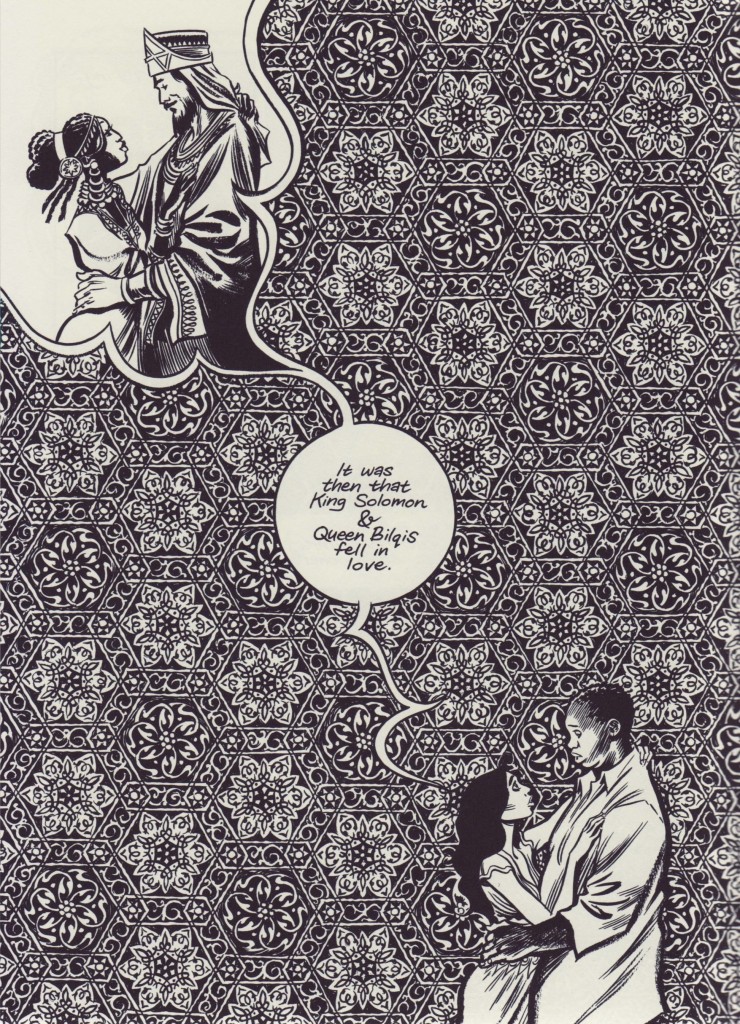

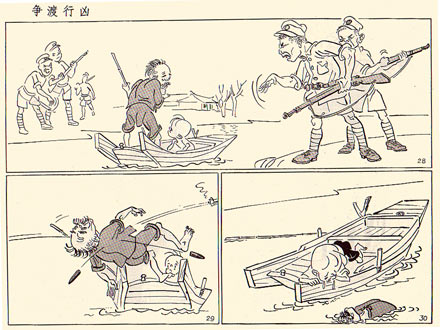

A young Ambedkar is denied the right to water as an untouchable.

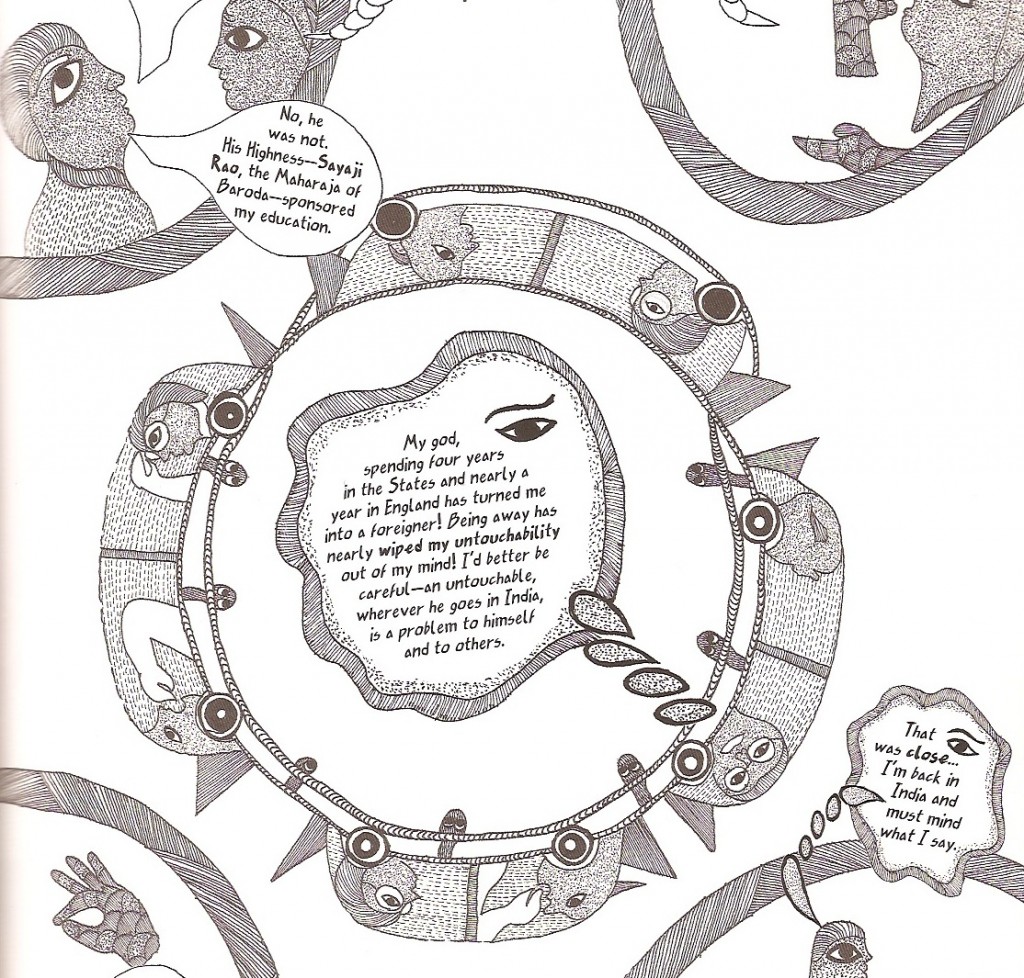

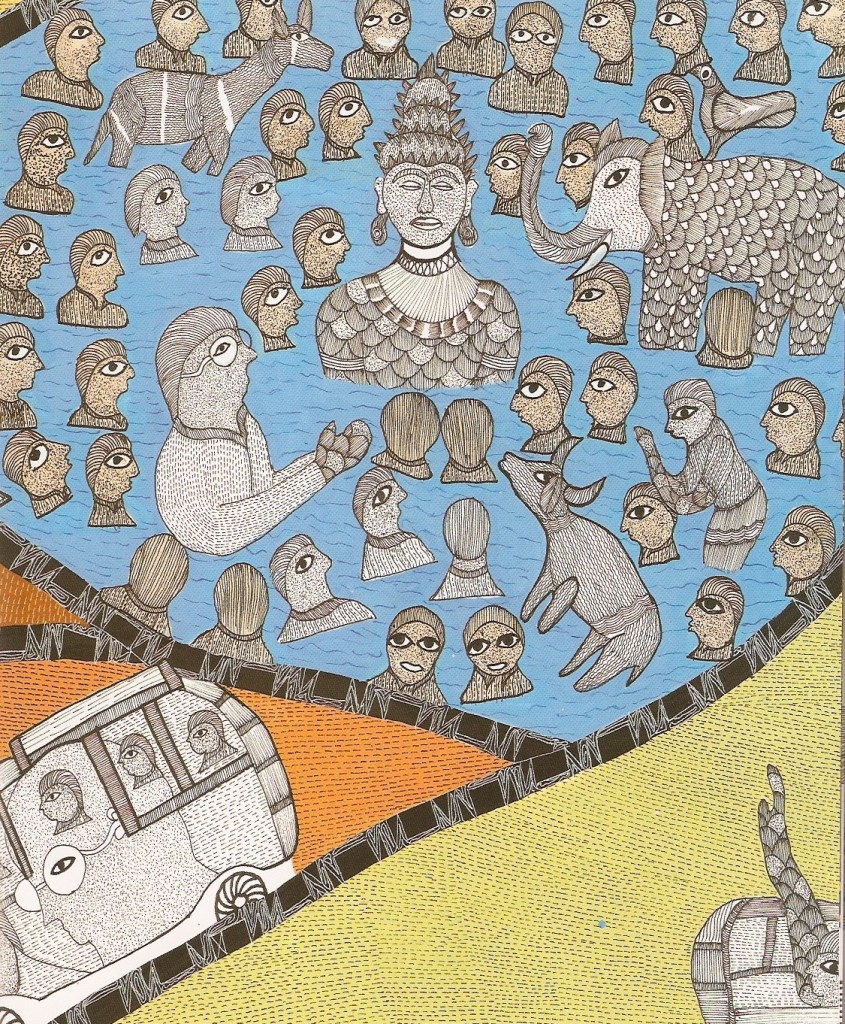

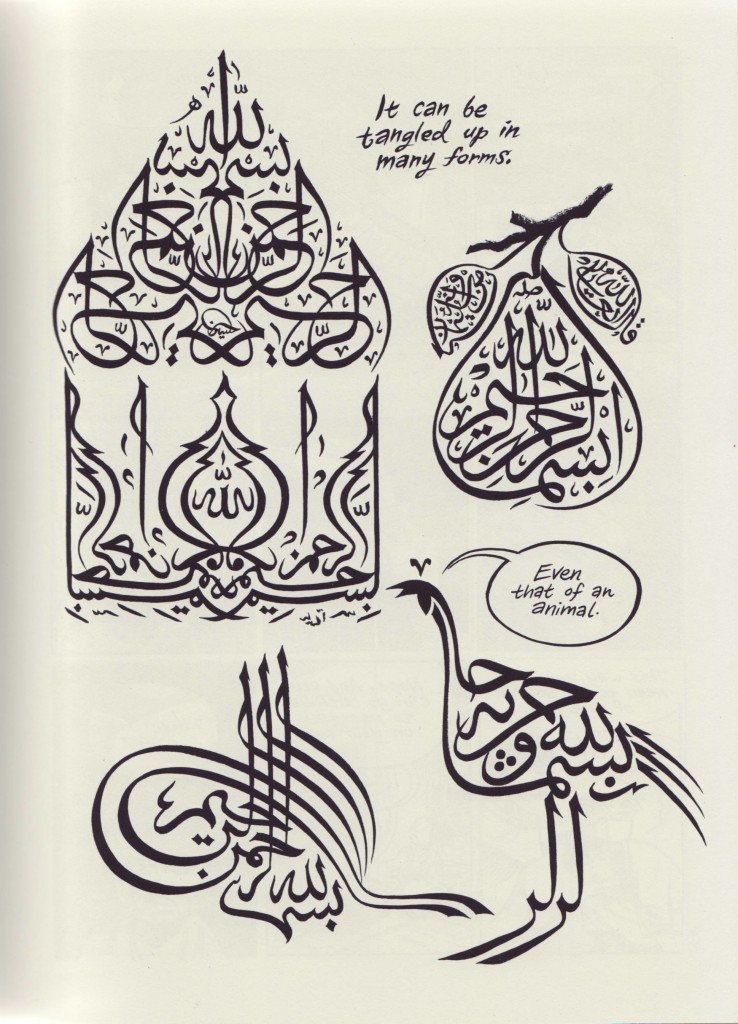

In a beautifully abstract way, the Vyams take a story scripted by S. Anand and Srividya Natarajan and strip it of many signifiers of Western sequential art through their own heavily detailed illustrations. For example, Ambedkar (the only constant character between vignettes) rather awesomely does not appear in a consistently drawn way throughout the book. As S. Anand recounts in Bhimayana‘s afterward — actually its “Digna” — while he dutifully provided the Vyams with a primer on graphic novel luminaries ranging from Eisner to Spiegelman to Tezuka to Satrapi, they rejected these influences: “We’d like to state one thing very clear from the outset. We shall not force our characters into boxes. It stifles them. We prefer to mount our work in open spaces. Our art is khulia (open) where there’s space for all to breathe” (p. 100). The result of this determined openness is a narrative that weaves different moments from Ambedkar’s life in a loose chronological order and produces a collection of pages that function both as a “graphic novel” and a distilled showcase of Pardhan Gond art.

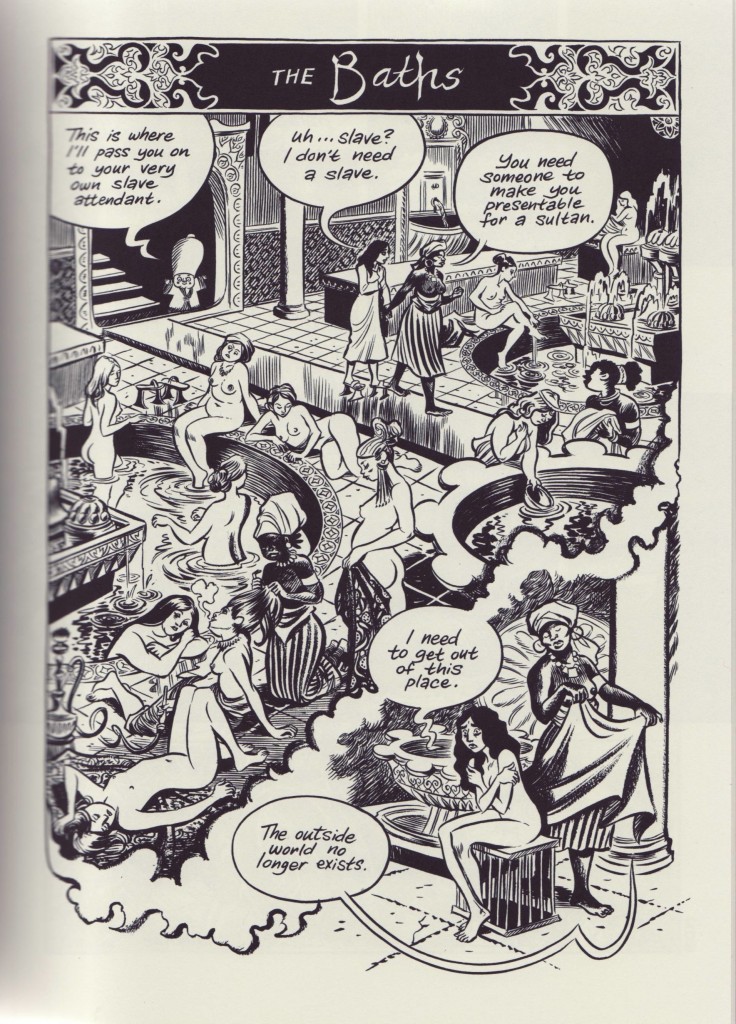

An example of how the Vvyams abstract notions like travel (this scene is of a re-caste affirming train conversation Ambedkar has after returning to India from the England) into a single page which serves as both a Pardhan Gond art painting and a narrative sequence.

While the larger Gond tribe of central India has a centuries long heritage of oral story telling, the Vyams are members of a more recent subset clan of artists called the Pardhan Gonds. The Pardhan Gond bards were formed in the early-1980s as artists that were dedicated to transmitting older Gond ritual performances into narrative visual art using everything from silkscreen prints to acrylic paintings to detailed ink drawings. Therefore, the most ingenious part of Bhimayana is Navayana’s idea to pair two talented Pardhan Gond artists — who were already creating a distinct form of “sequential art” — with the globally buzz-worthy format of “graphic novel”; effectively repackaging the forgotten and overshadowed legacy of a civil rights leader in India into something worth tweeting about. Case in point: I, resident of California, didn’t know who Ambedkar was before reading Bhimayana, and I surely wouldn’t have heard of Bhimayana if it weren’t a comic. And let’s say I had been curious enough to skim a biography of Ambedkar on Wikipedia, that medium wouldn’t have provided me with the ample space to connect with India particular issues like Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism through powerful artwork:

The clever conceit behind Bhimayana is a striking example of how Navayana lives up to its name of being a “new vehicle” for old ideas. Put differently, the book makes critically talking about caste sexy in the way that social justice topics rarely are. The salience of framing an issue for a global audience is one that Ambedkar himself seems to have understood very well throughout his struggle to challenge the caste system. After a 1923 decision by the Bombay Legislative Council to allow untouchables to use all public resources as basic as education and water — services that Ambedkar had been denied growing up as a Dalit — he gave a speech asserting the inalienable rights known in the Dalit movement as the “Declaration of Independence”:

“If we seek for another meeting in the past to equal this, we shall have to go to the history of France: the revolutionary French National Assembly convened in 1789 that set new principles for the organization of society. … People forget that if the rulers of France had not been treacherous to the Assembly, if the upper classes had resisted it, it would have had no need to use violence in the work of the revolution. We say to our opponent too: Please do not oppose us. Put away the orthodox scriptures. Follow justice.”

Just as Ambedkar frames an Indian human rights struggle in the context of a recognizable Western one, Navayana’s editor-in-chief S. Anand seems to understand the value in reframing intellectual human rights arguments in the medium of comic art. In this way S. Anand is like the protagonist of the story he wrote: using universal signifiers to address an India-specific issue. This point dredges up a deeper favorite question of mine: who exactly is the intended audience of Bhimayana? As with some of its more relatively famous contemporaries (par example Persepolis) reading Bhimayana can bring up a lingering fear that the book is seeking “First World” readers to make money from “Third World” problems. Ultimately, this line of questioning doesn’t hold enough weight against the beautiful education that Bhimayana provides to non-Indian readers like myself. Although, it should be noted that a similar thought might have been pondered by Navayana, who announced ahead of their 2012 Angoulême appearance that Bhimayana will see new editions in five Indian languages later this year.

This brings us to A Gardener in the Wasteland (2012), Navayana’s most recent stab at providing a forum for anticaste ideology in the world of comics. A Gardener digs back even further into the history of anticaste reformers to tell the story of Jotiba Phule (1827-1890) and his wife Savitri Phule (1831-1897). The Phules were fierce critics of caste-based exploitation by brahman’s (the highest caste in the Hindu system) under British rule and lifelong campaigners for women’s education in India who opened the countries’ first school for girls in 1948. A Gardener is written by Canadian-based Srividya Natarajan and is drawn by New Delhi-based artist Aparajita Ninan, with the text itself based predominately on Jotiba Phule’s 1873 work Slavery. Impressively, the female transglobal team bring Phule’s 1873 writing to life in a way that feels like a product that is relevant in 2012.

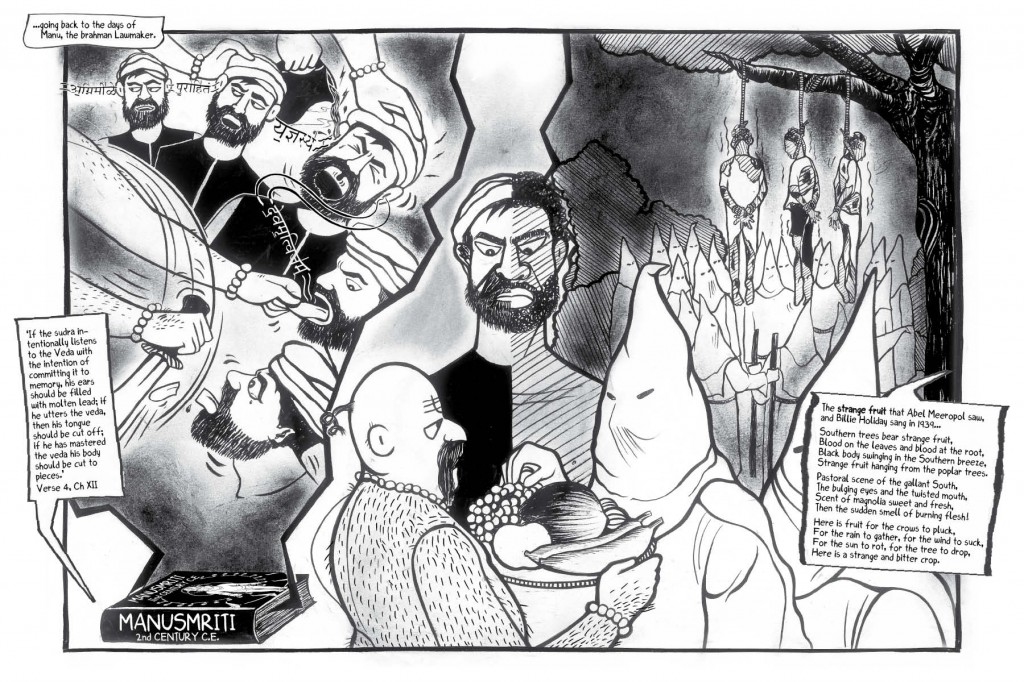

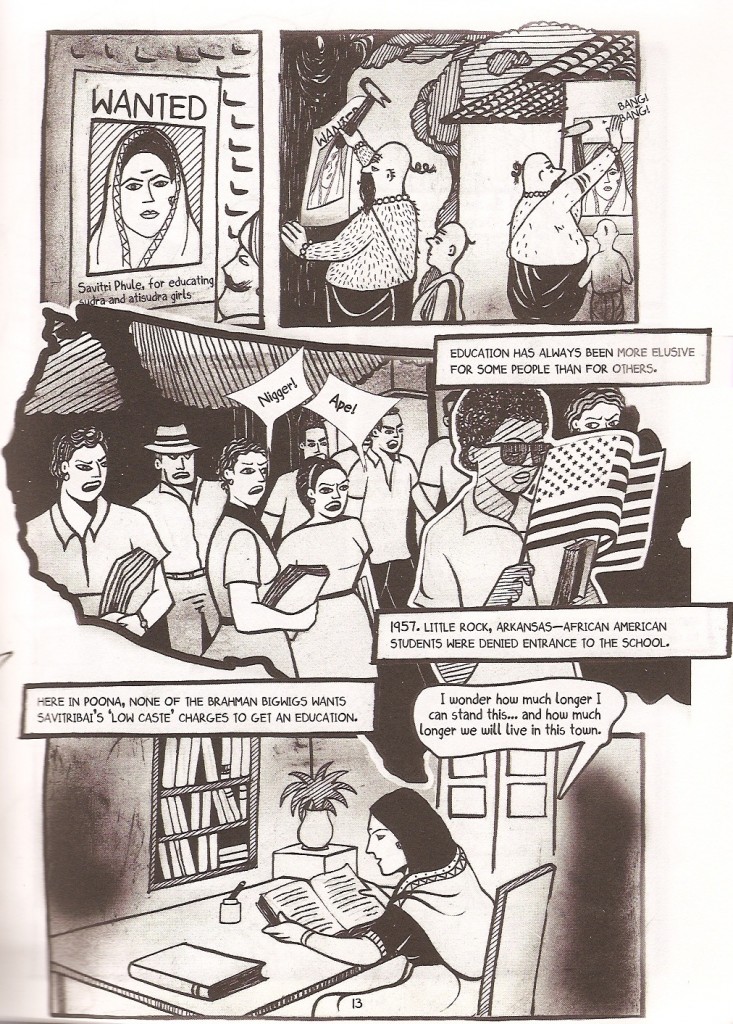

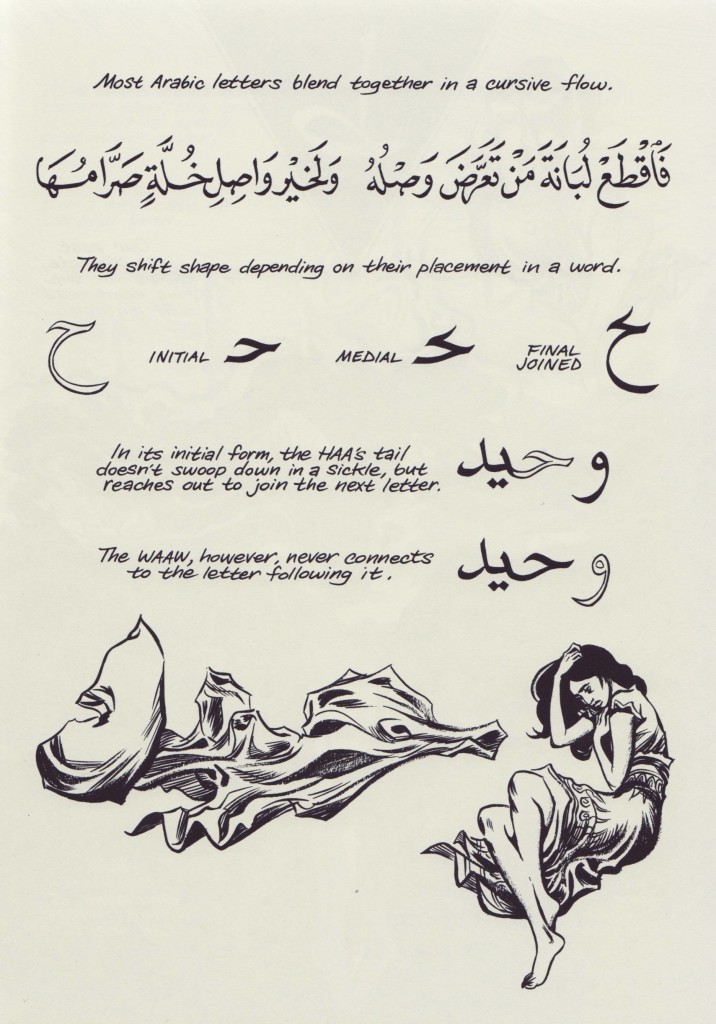

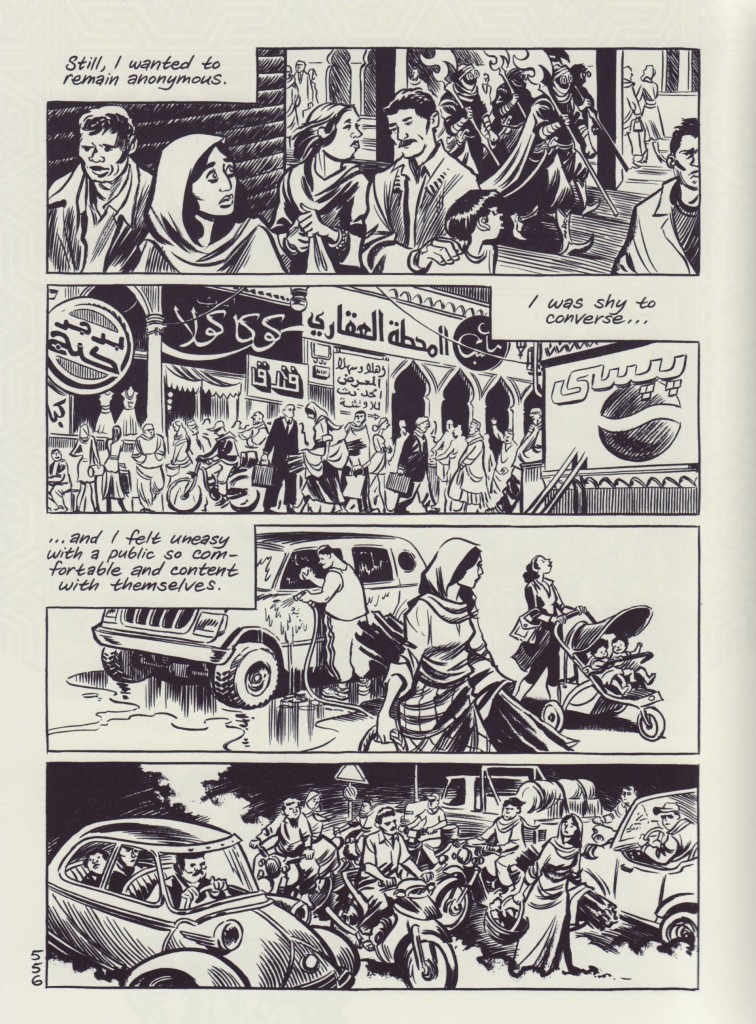

Throughout the book Natarajan and Ninan engage in the same sort of re-framing that is prevalent in Bhimayana, this time building on Phule’s comparisons of archaic notions of Caste hierarchy to slavery in the United States. Where Phule saw the way the brahman’s exploit those in lower castes as akin to slavery, Natarajan and Ninan extend the metaphor to compare the lives of the Phule’s to those of U.S. civil rights leaders. For example, the hardships Savitri Phule endures trying to educate women is met with an echo panel of segregation in the the South, in effect tying the histories of oppression to one another:

While the American history shorthand gets the point across efficiently, it is when re-framing moments like this that Natarajan and Ninan hinder their otherwise strong debut. At several points A Gardener in the Wasteland produces comparisons that feel overly heavy-handed, instead of letting the fascinating tale of the Phule’s fight against an established hierarchy subtly speak for itself. While it is easy to understand why the creators felt the need to draw somber parallels when telling such a reverential story, those parallels leave the book overly stuffed with asides that weaken the narrative flow for the benefit of readers like me. Put differently, I rather feel lost in the world of an artists’ imagination and grapple to find meaning than be spoon fed educational antidotes from my own frame of reference.

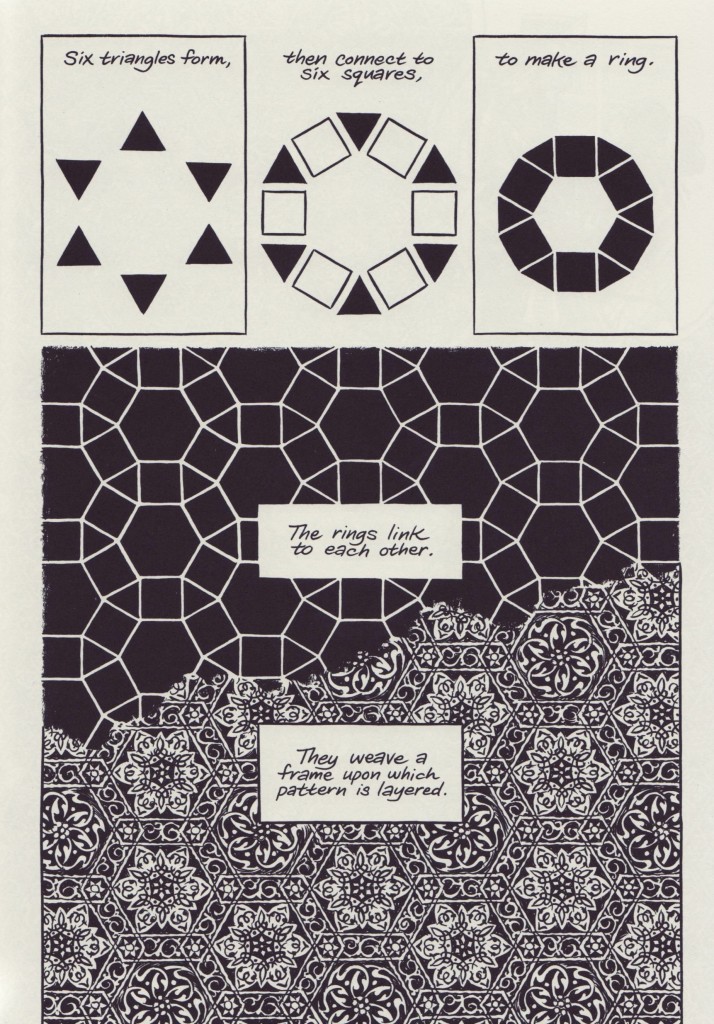

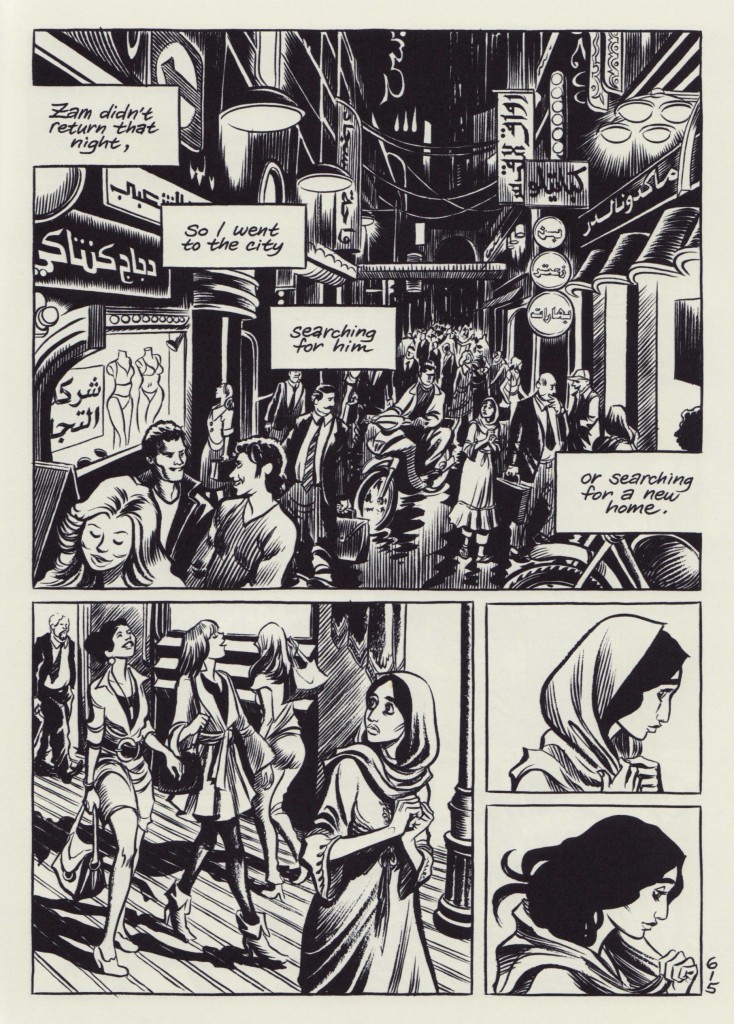

A spread which compares brahman lawmakers to the Klu Klux Klan

If A Gardener in the Wasteland feels like a mediated success, it is predominately mediated by the innovation on display in Bhimayana. While Bhimayana uses artwork to interpret a narrative loosely, A Gardener often skews towards using its strong art for straightforward exposition. The moments where A Gardener succeeds at becoming a “new vehicle” are when it forgoes panels and Westward analogies in favor of the cleverness found in the pages of Phule’s anticaste arguments. The best example of how A Gardener takes a risk with content to produce something unique is an extended midsection which walks readers through a socratic discussion between Jotiba Phule and his friend where Phule challenges many of the assumptions on which the brahman base their caste based view. In what has become the lynchpin of the book’s marketing campaign, A Gardener illustrates an argument that has Brahma (the father of the brahmans) menstruating out of his mouth. It is in the moments like this where Ninan is having clear fun with her art that make Phule’s 19th Century argument feel 21st century compatible.

The success of both of Navayana’s graphic novels is recasting biography of anticaste leaders as intriguing graphic novel. Bhimayana and A Gardener work towards this goal from different starting points, but they both end up as strong debuts in the global comics landscape. For a long-form comic to balance entertainment, technical skill, and Theory is not easy, which makes it somewhat remarkable that out of the gate Navayana has two comics that pull of such an act. Bhimayana and A Gardener in the Wasteland are worth receiving the spotlight not just because they are Indian, but because they are good.

—

Navayana books can be purchased from Scholars Without Borders.

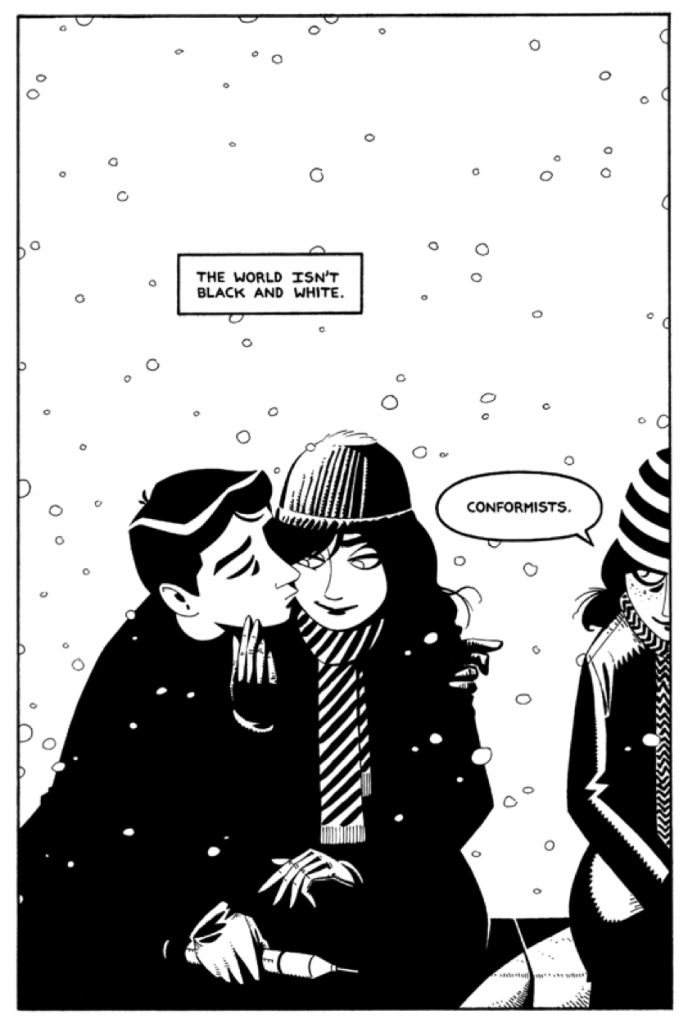

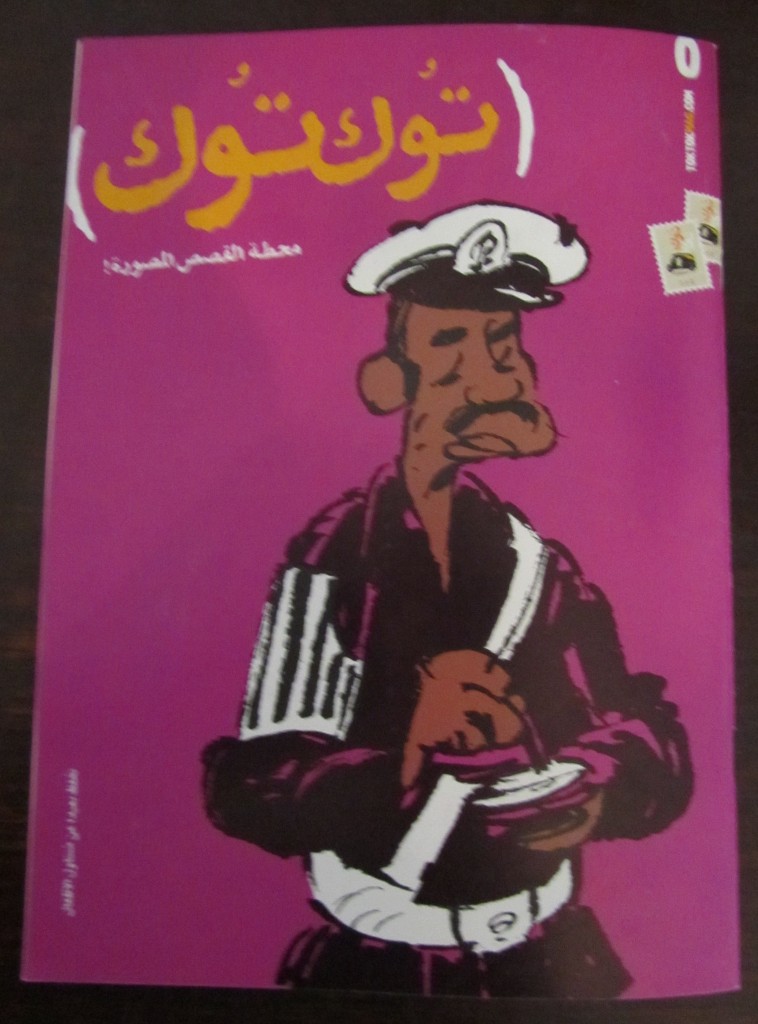

In the premier issue the staff offers an answer to “What is Samandal?”

In the premier issue the staff offers an answer to “What is Samandal?”

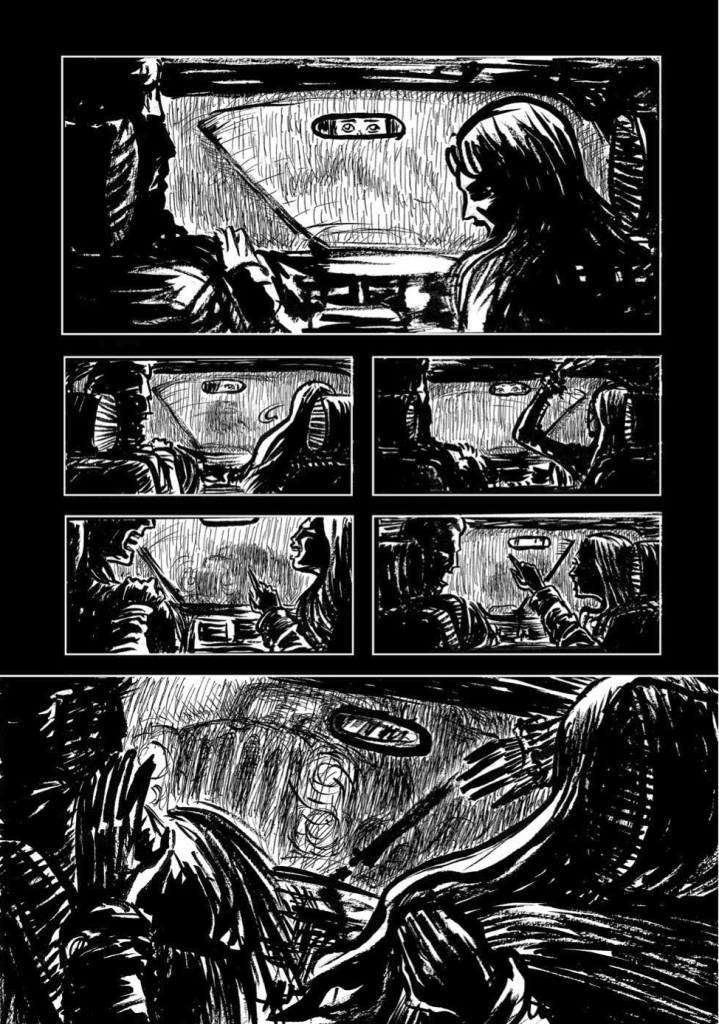

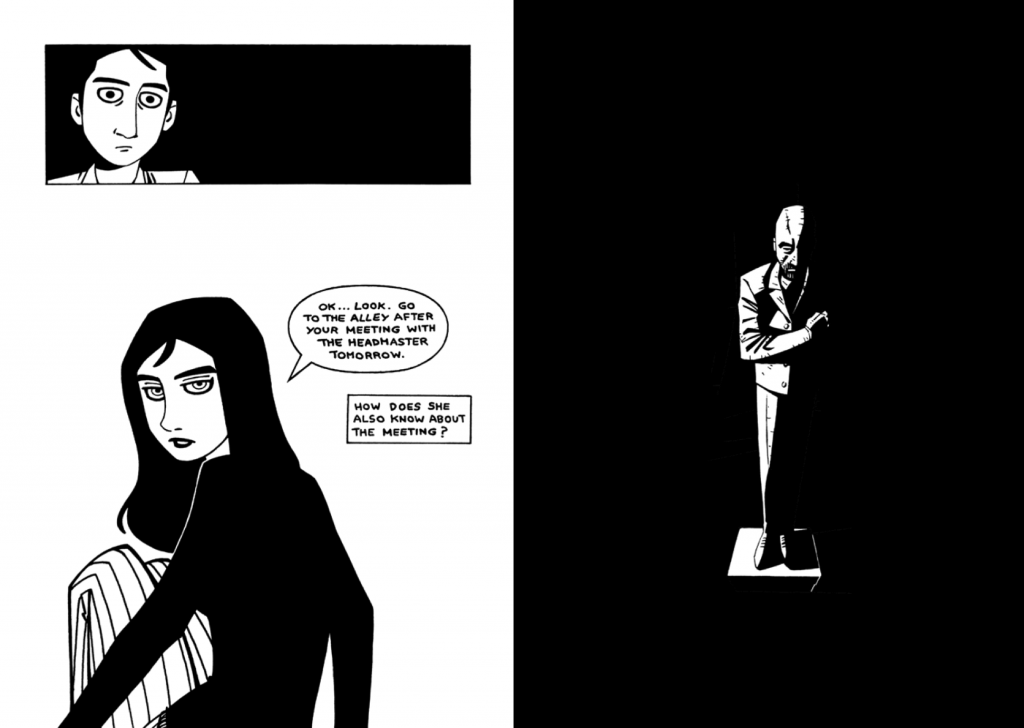

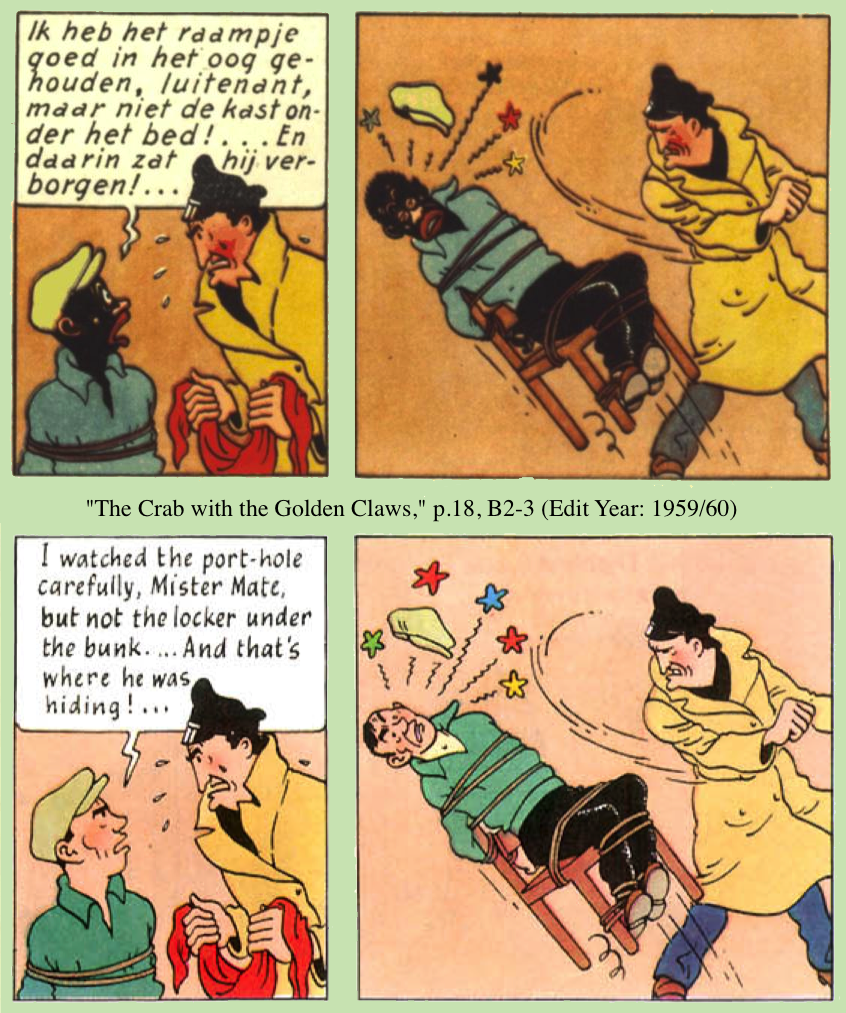

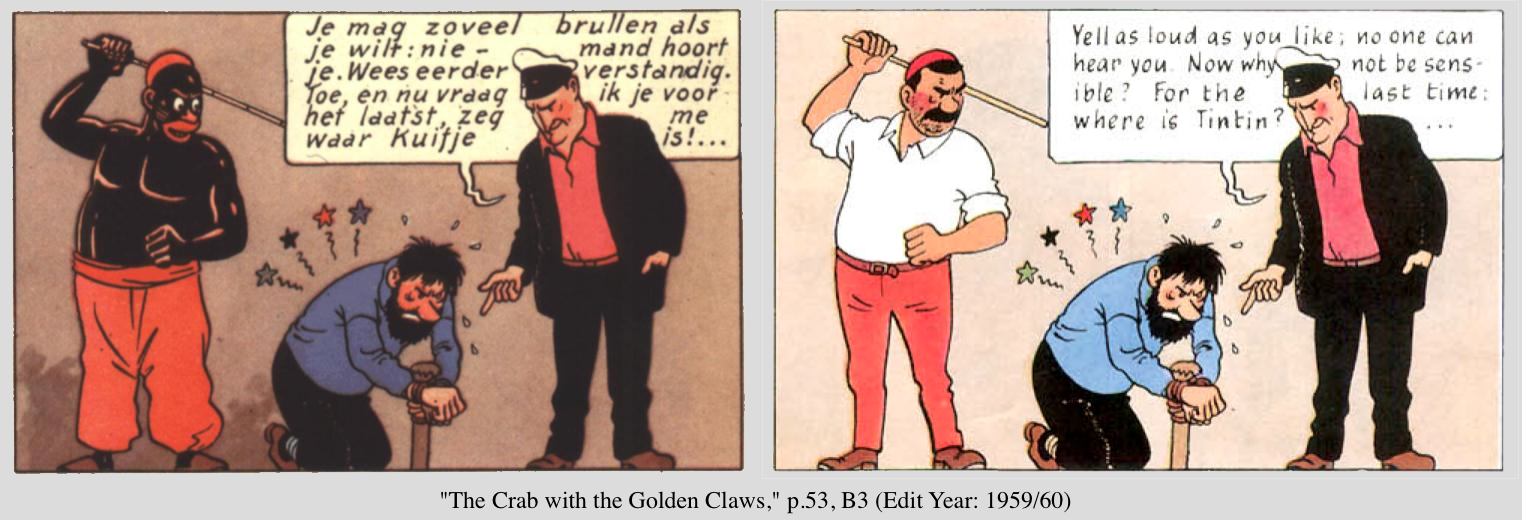

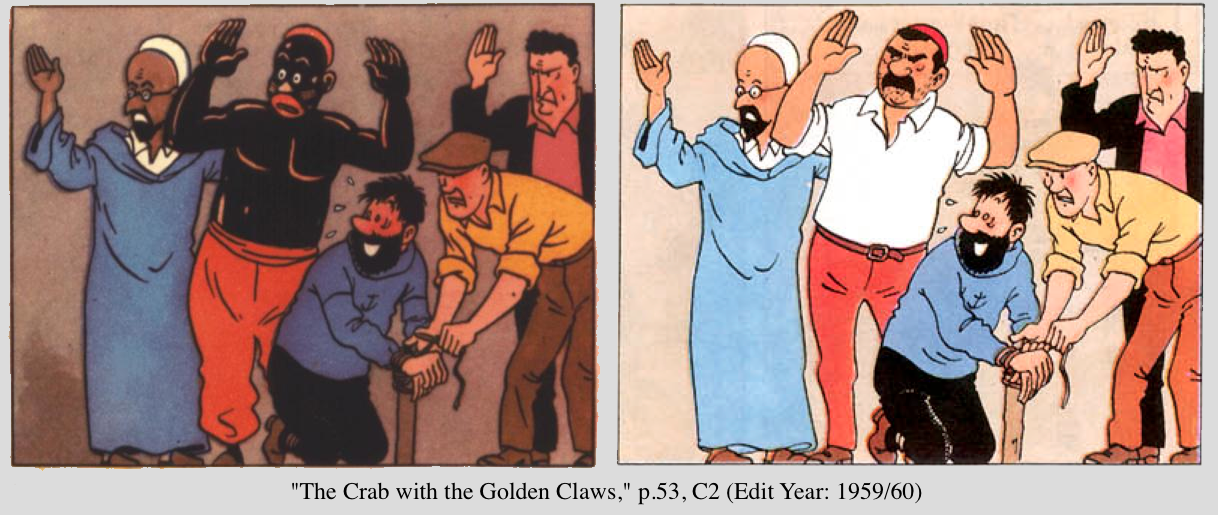

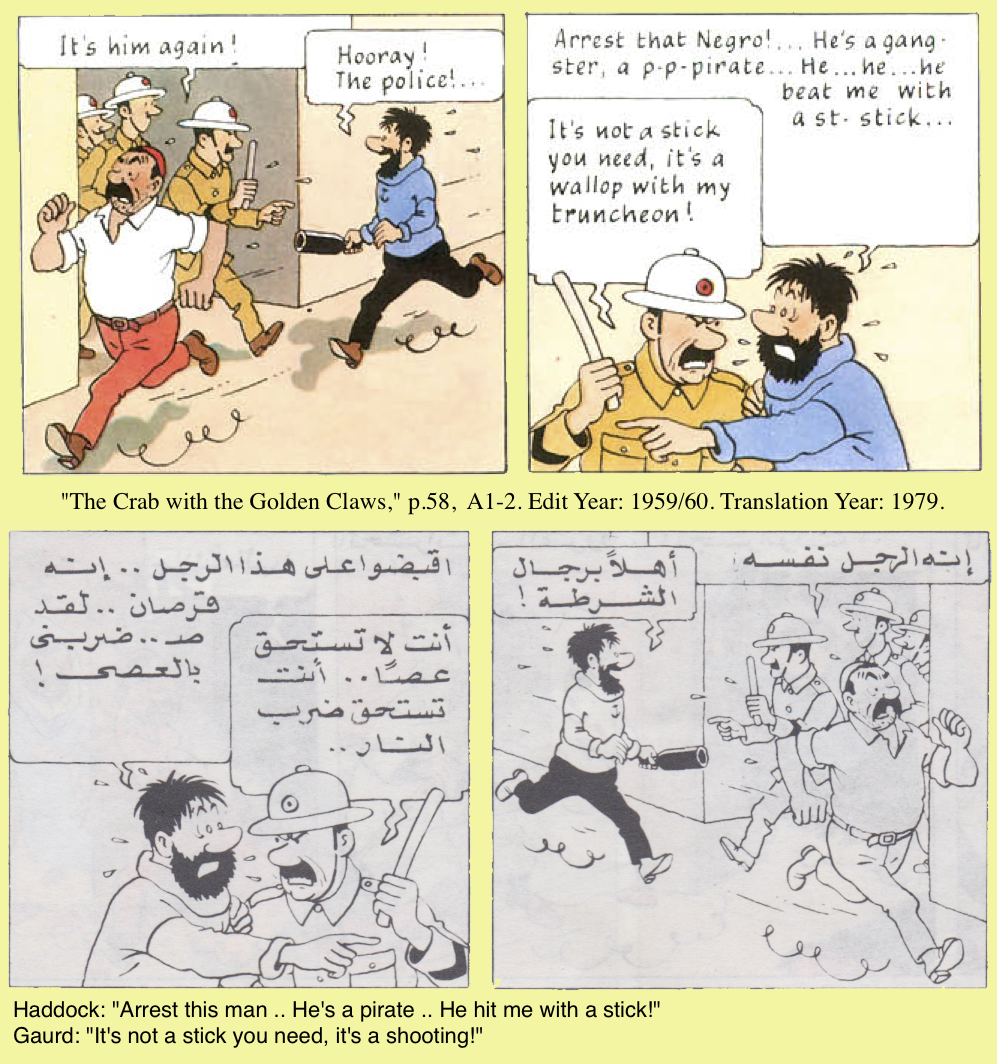

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.

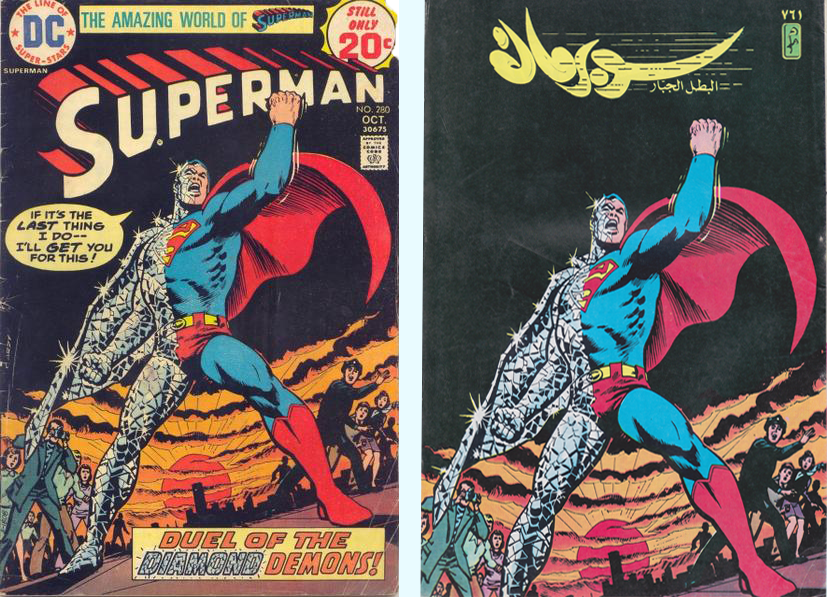

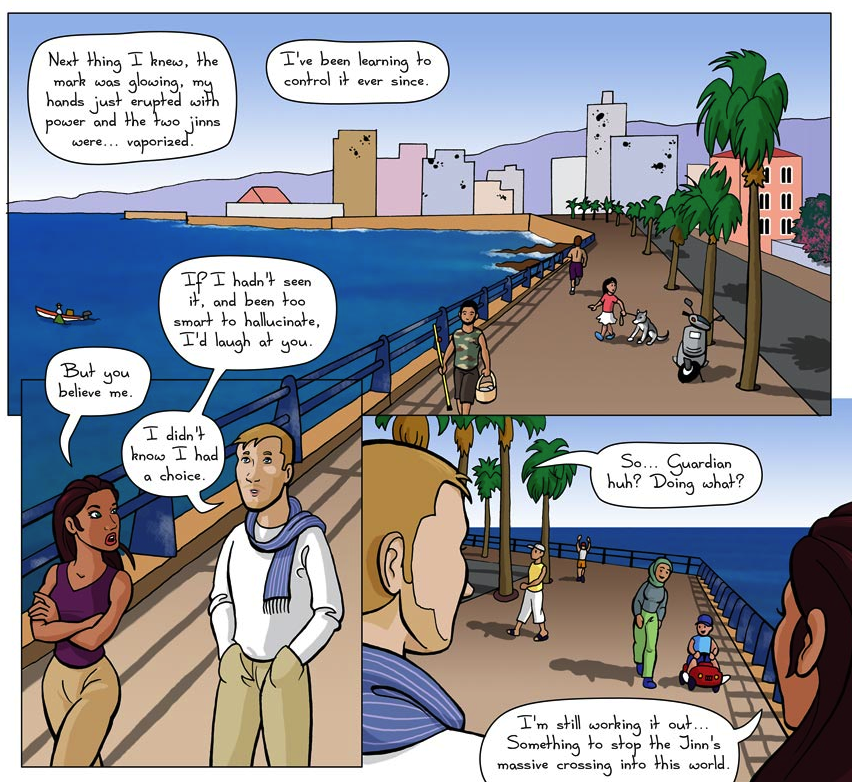

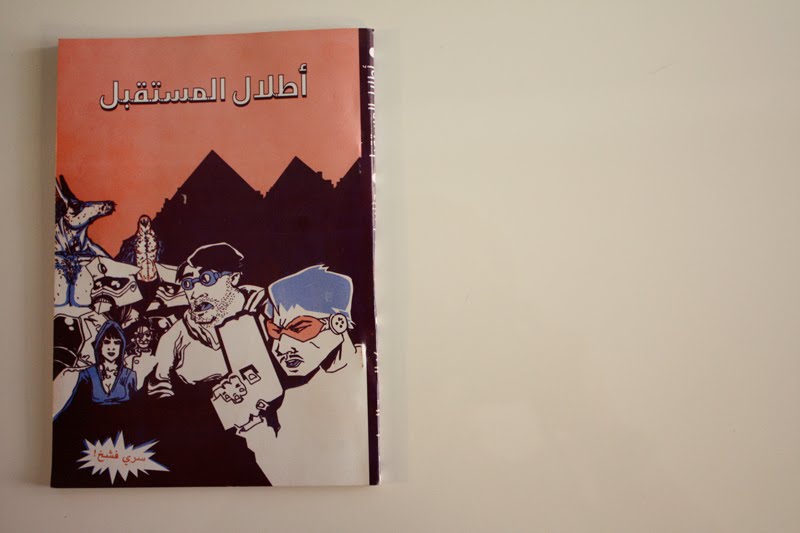

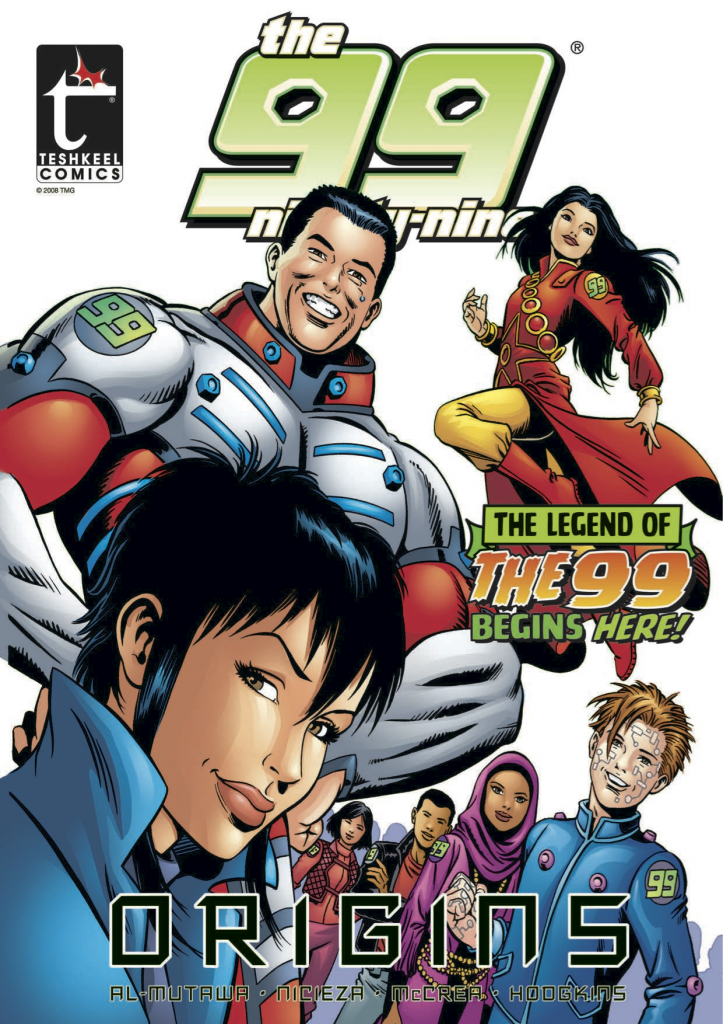

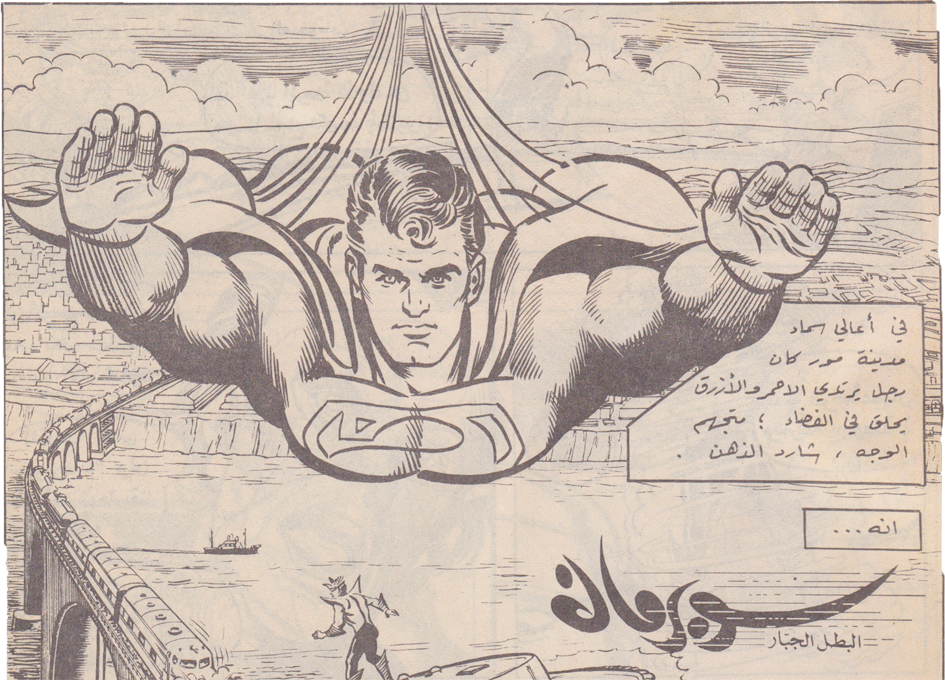

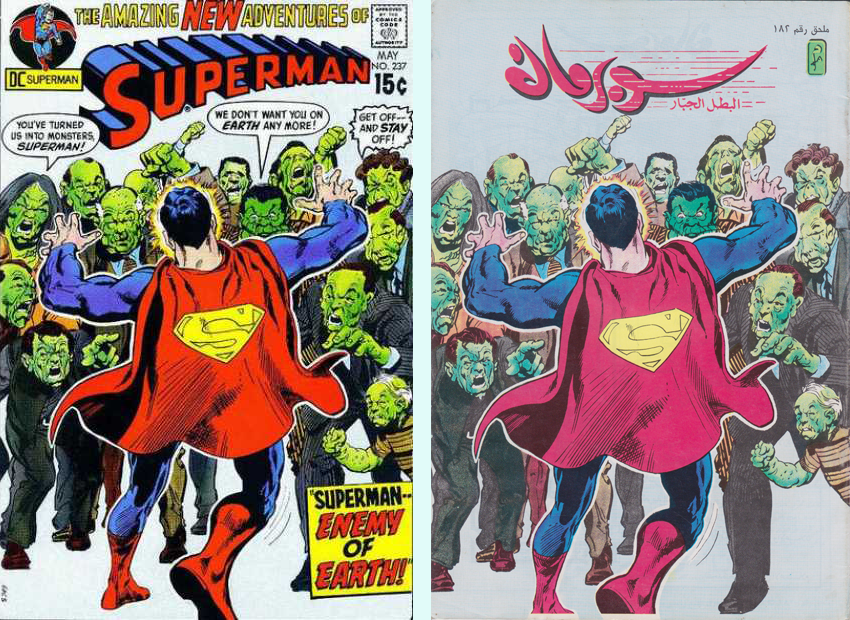

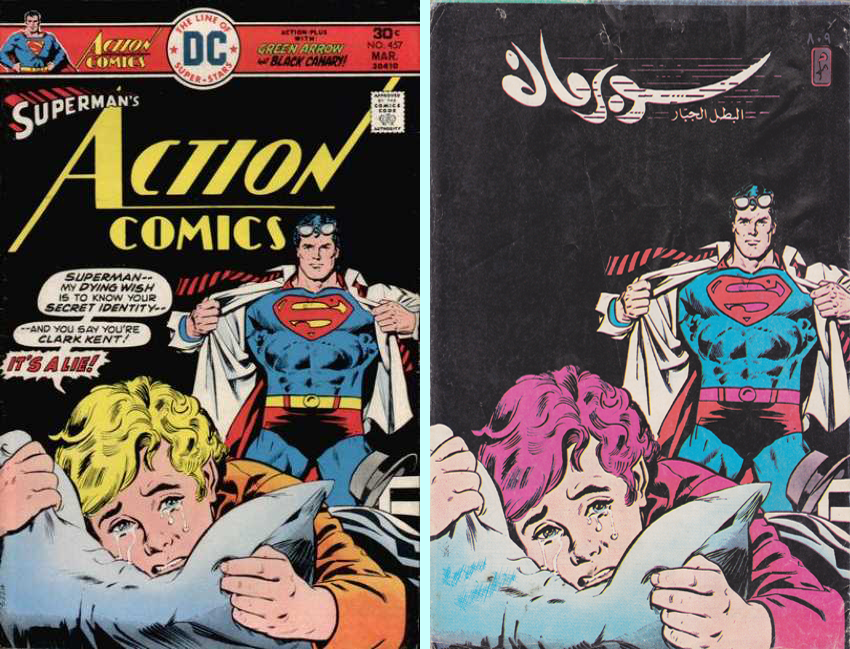

English covers via the archive at

English covers via the archive at