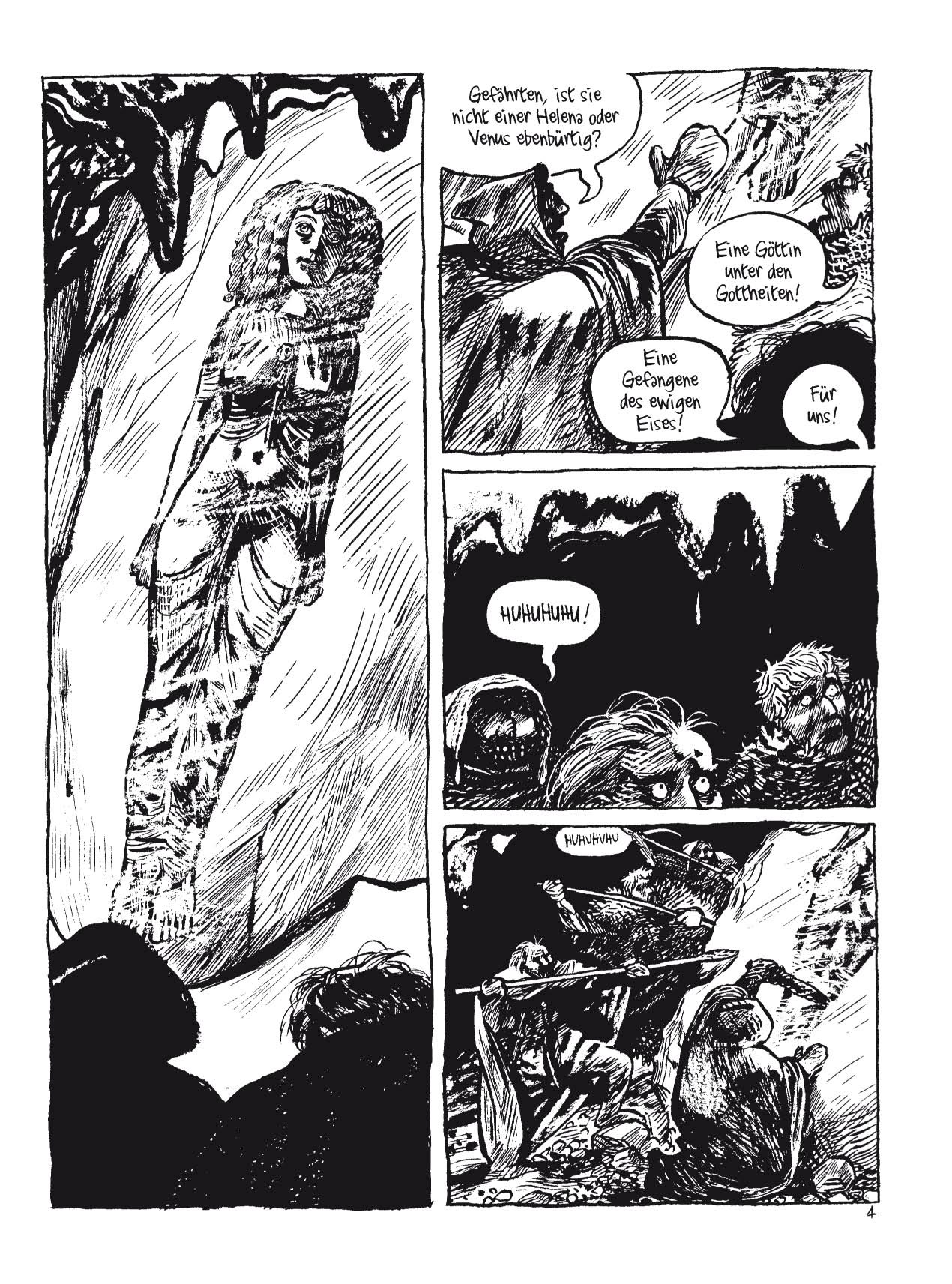

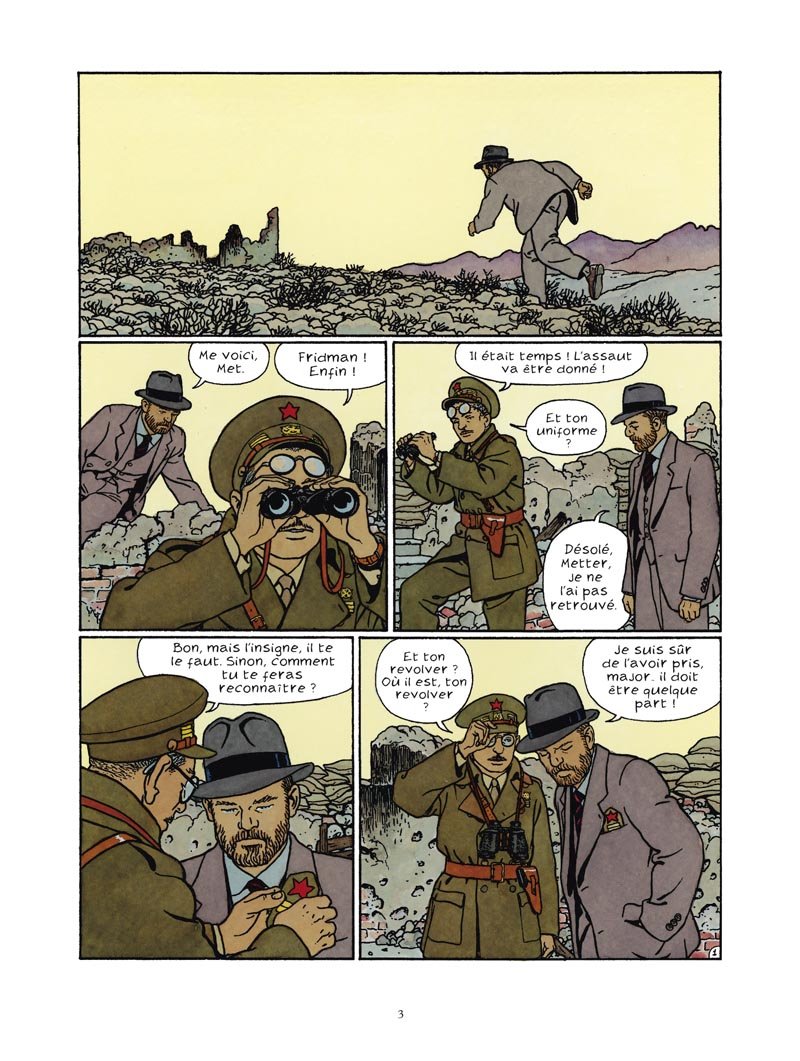

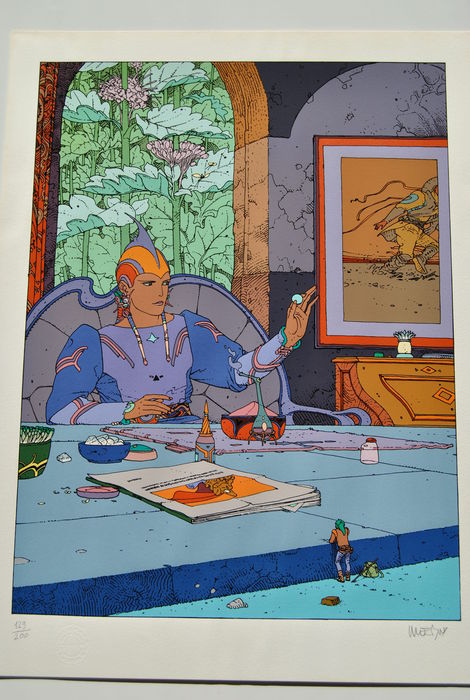

“…. a grand, strange dream of ancient Rome. At the edge of the empire, a gang of bandits discovers the body of a beautiful woman in a cave; she is encased in ice but may still be alive. One of the bandits, bearing a stolen name and with the frozen maiden in tow, makes his way toward Rome—seeking power, or maybe just survival, as the world unravels…. Peplum weaves together threads from Shakespeare and the Satyricon along with Blutch’s own distinctive vision.”

Blutch (Christian Hincker) is the 2009 winner of the Grand prix de la ville d’Angoulême.

Is there any suggestion that Blutch’s Peplum is inspired by the Satyricon of Petronius apart from the fact that the author has told us so?

There is the presence of the protagonist’s young male lover, Giton, as well as the licentious poet Eumolpus (both unnamed in the comic but central figures in Petronius’ work). There are also at least two instances where Petronius’ Satyricon is “quoted” if not wholly then at least in part.

Yet the comic is fixed in a strange but plausible landscape; it is less earthy, less strange and altogether less theatrical and decadent then the book and Fellini’s film. Both the original and film versions of Satyricon are filled with the rank physical reality of sex, not the curious delusion which Blutch’s protagonist engages with throughout.

If anything, Peplum is a kind of delightful mongrel taking in the high adventure of the pepla genre, the theatricality of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, the moral entertainments of Eric von Stroheim’s Greed (or even The Treasure of Sierra Madre) as well as Petronius’ fitful and (for historical reasons) fragmented narrative. Edward Gauvin (the translator; citing Blutch himself) suggests the strong influence of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Medea, presumably for its tribal motifs, strange accouterments, sparse landscapes and ritualized violence. All of this told in a virtuoso voice laced with a smattering of European high culture and Blutch’s own conception of the pagan world. The adventure and the splendid drawing is what keeps Blutch’s audience engaged as the artist’s mind wanders across this landscape of high and low.

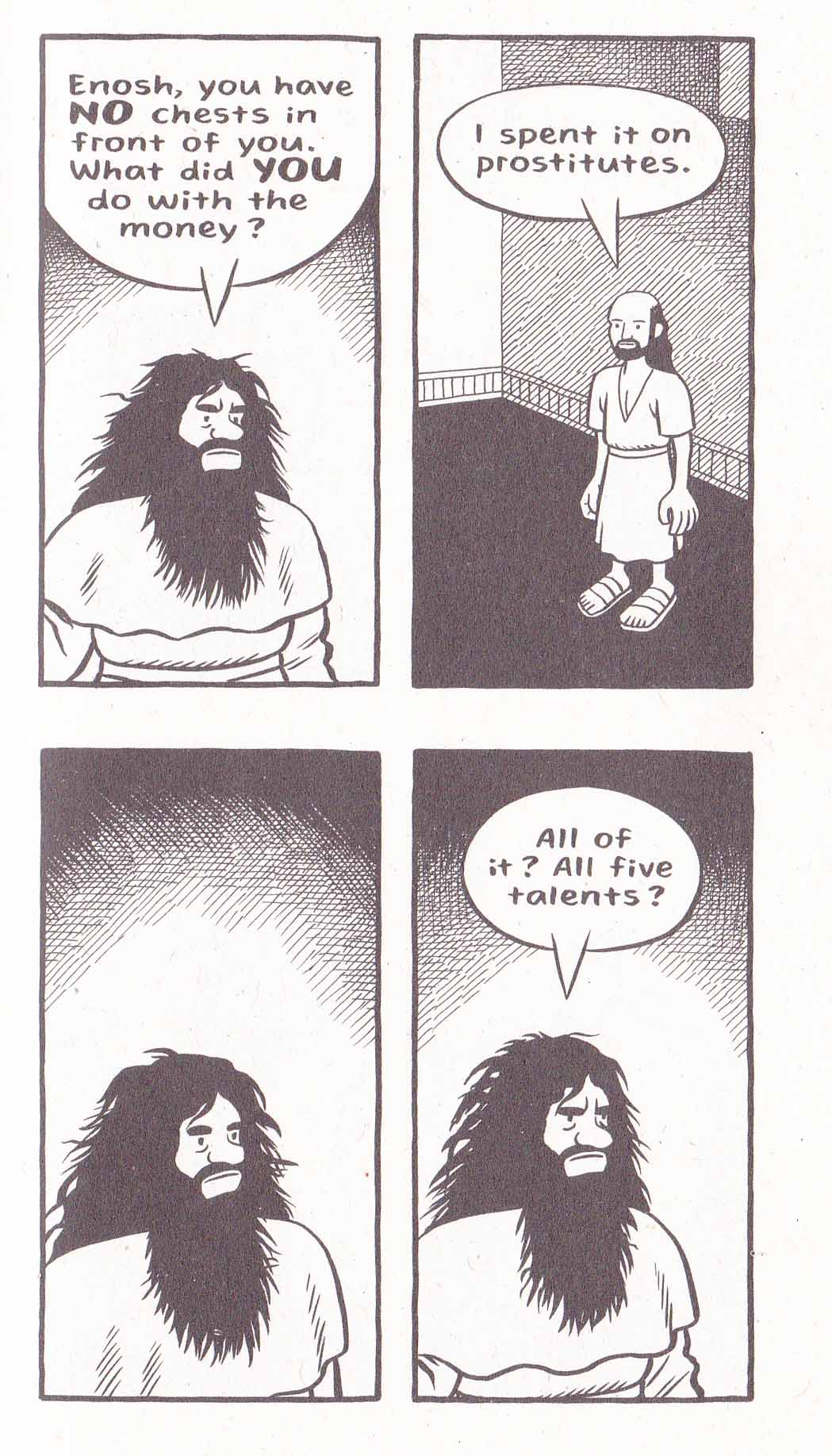

Yet it must be said that even this synthesis has its counterpart in Petronius’ novel. The most famous and well preserved section of the Satyricon is that section known as Trimalchio’s feast where there is an equally debauched mixture of excess and high culture. Here, for example, is the rampant luxury of overeating mixed with recitations of Homer:

“So let’s start enjoying ourselves again, that’ll be better, and let’s watch the recitations from Homer.’

In came the troupe immediately and banged their shields with their spears. Trimalchio sat up on his cushion and while the reciters spouted their Greek lines at one another in their usual impudent way, he read aloud in Latin in a sing-song voice.”

It seems improbable that Peplum was cast together haphazardly if only because of its rhetorical symmetry. As Gauvin, relates in his introduction:

“[Jean-Louis] Gauthey commissioned an epilogue from Blutch and devised the book’s structure: Ten chapters prefaced with new vignettes and chapters heads.”

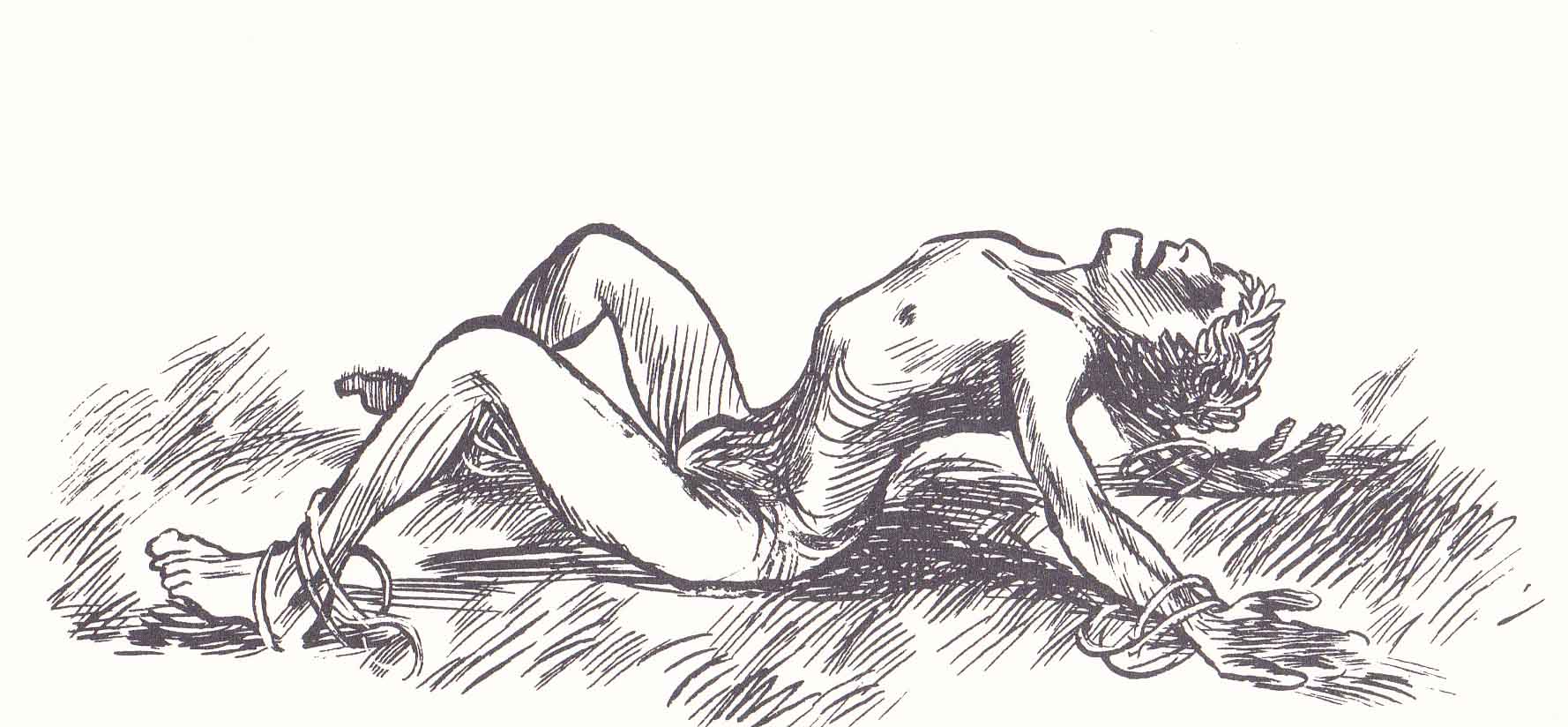

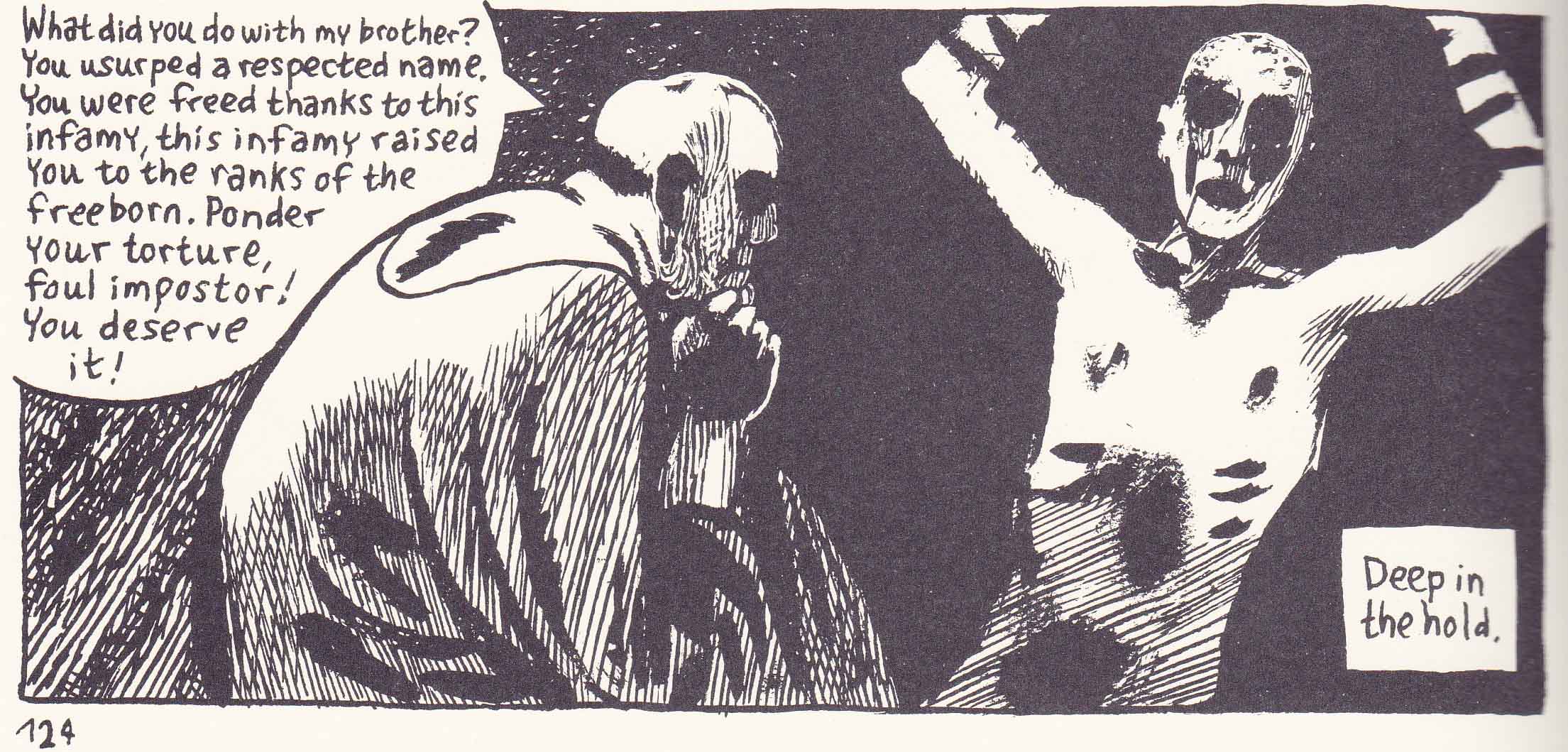

The album begins and ends with Encolpius greeting his goddess, first as a miraculous vision and at the end as a deathly visage. In our second encounter with Encolpius, he murders Publius Cimber in private and gains his name, while in the penultimate section of Peplum he kills a rabid woman perhaps to save his own life, perhaps to protect his very chastity. In the third chapter of Peplum, Encolpius is tortured by severe sea-sickness and asks for the merciful release of death; in the corresponding section in Chapter 8, he is tortured (on a ship) for posing as Publius Cimber by the brother of the same.

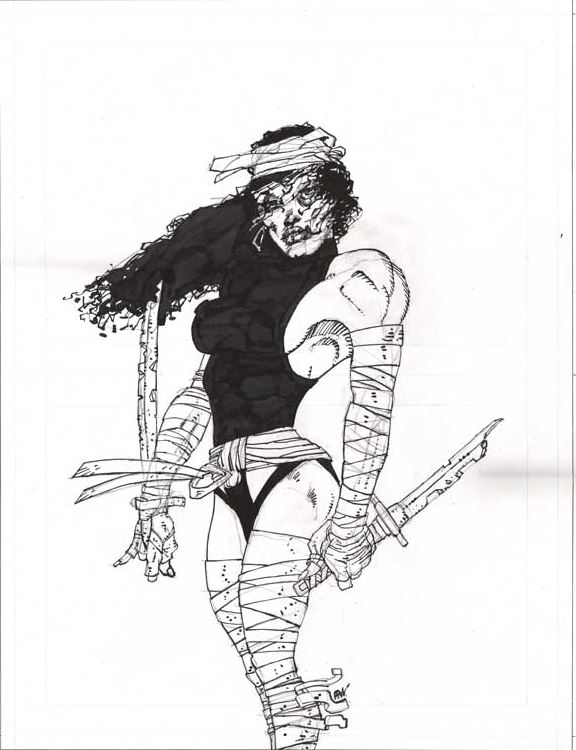

In the fourth chapter, Encolpius encounters a tribe of women with amputated limbs. He is tied down and pummeled by a rush of phallic arms and promptly ejaculates.

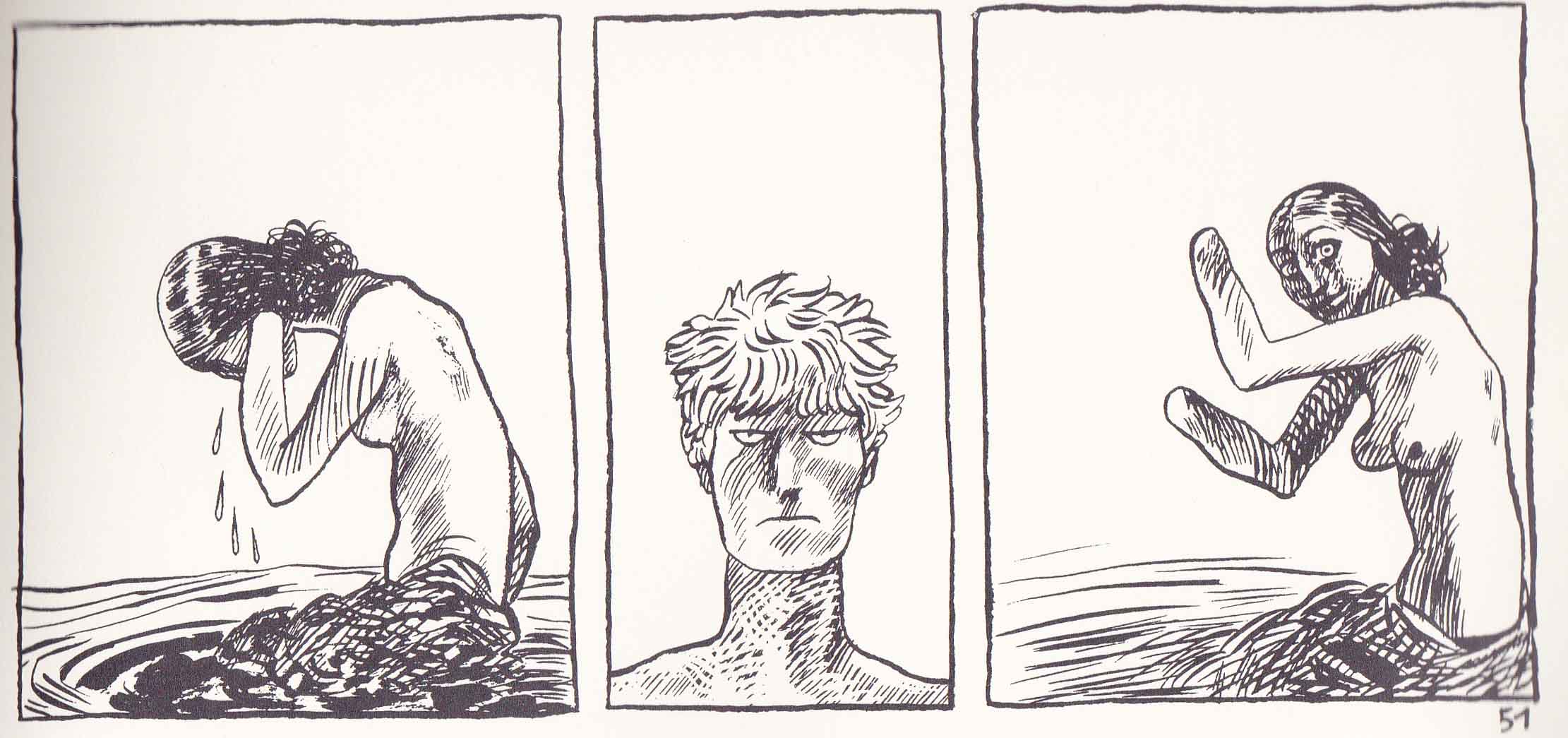

In the analogous seventh chapter, he longs for coitus with the most beautiful woman he has ever seen but is ultimately impotent. There is every reason to believe that Peplum is in part a study of repressed homosexuality. It will seem odd to state something so obvious but neither of the comic’s illustrious forebears seem the least bit concerned about the sexuality of its protagonists despite the rampant pederasty on display.

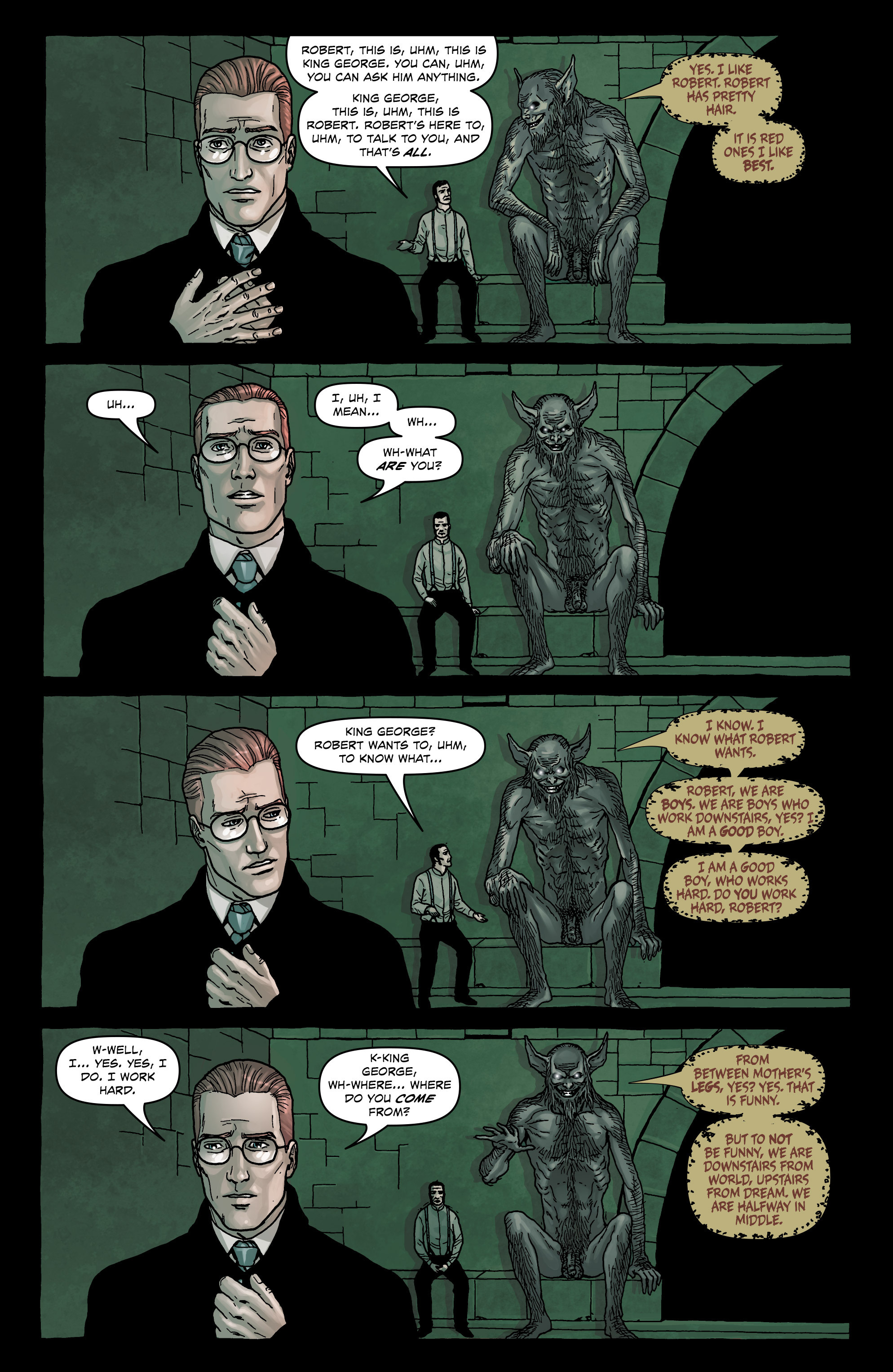

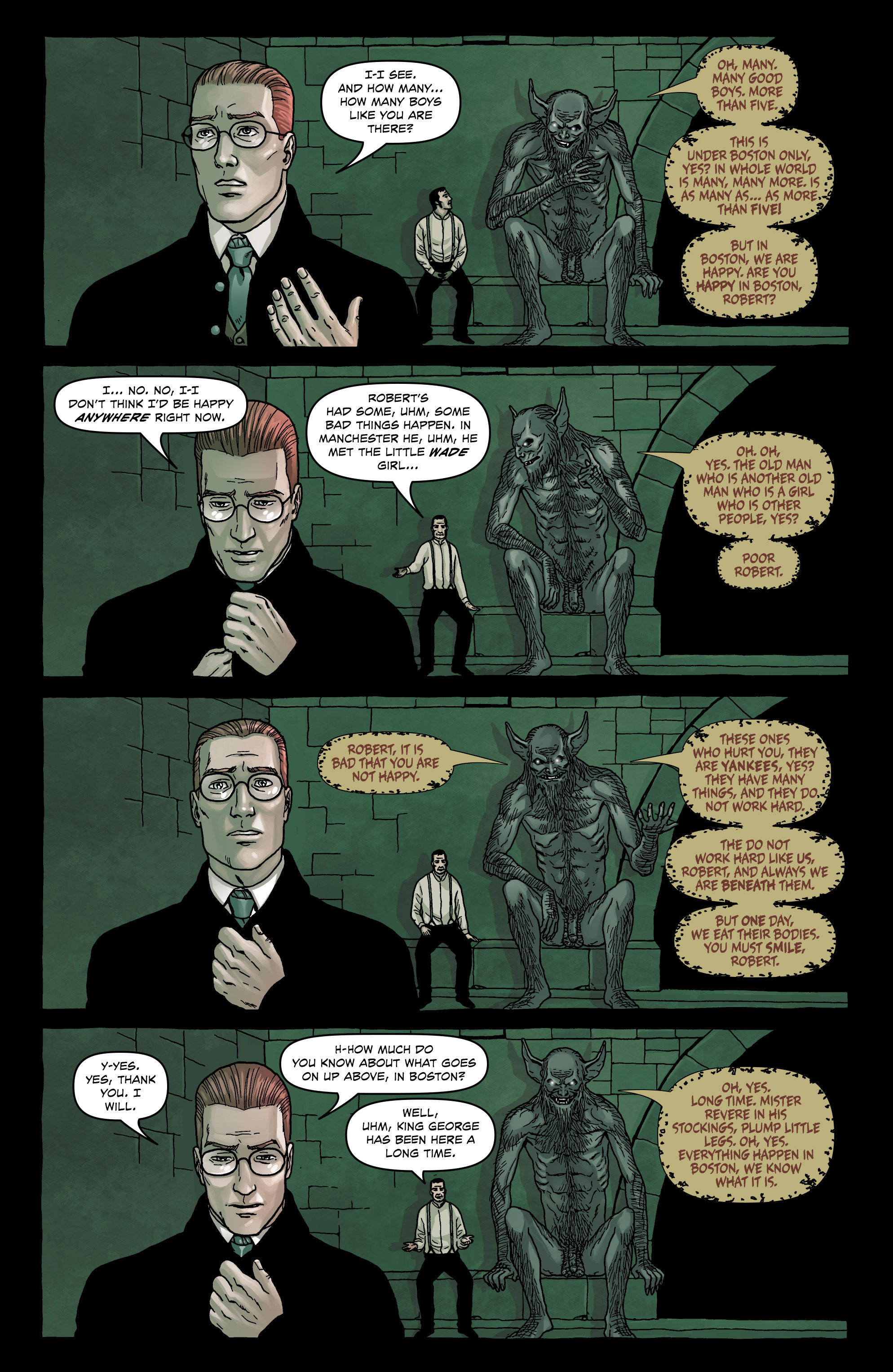

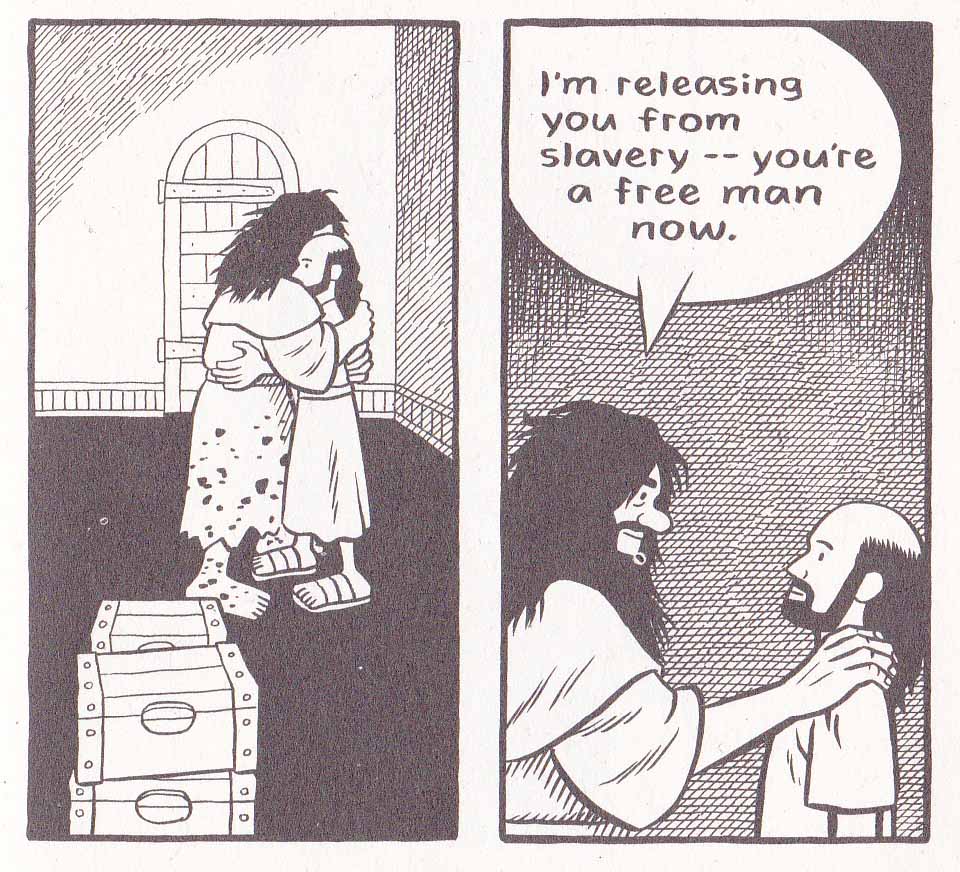

What the comics does share with the Satyricon is that element of class conflict, that vivid description of lower class Roman society coming into contact with the upper classes. Like Trimlachio, the wealthy freedman of the Satyricon, Encolpius has risen through the ranks if not in kind then at least in name. His shifting fortunes—first tortured for impersonating a noble man and then celebrated for the act of killing—reflects the way in which the “supernatural” was thought to have a part in the acquisition of wealth. When he finally reaches the center of empire in the epilogue, he is distinctly out of step, a stick in the mud. Peplum isn’t as rich as its source material in this respect but neither is this its central theme.

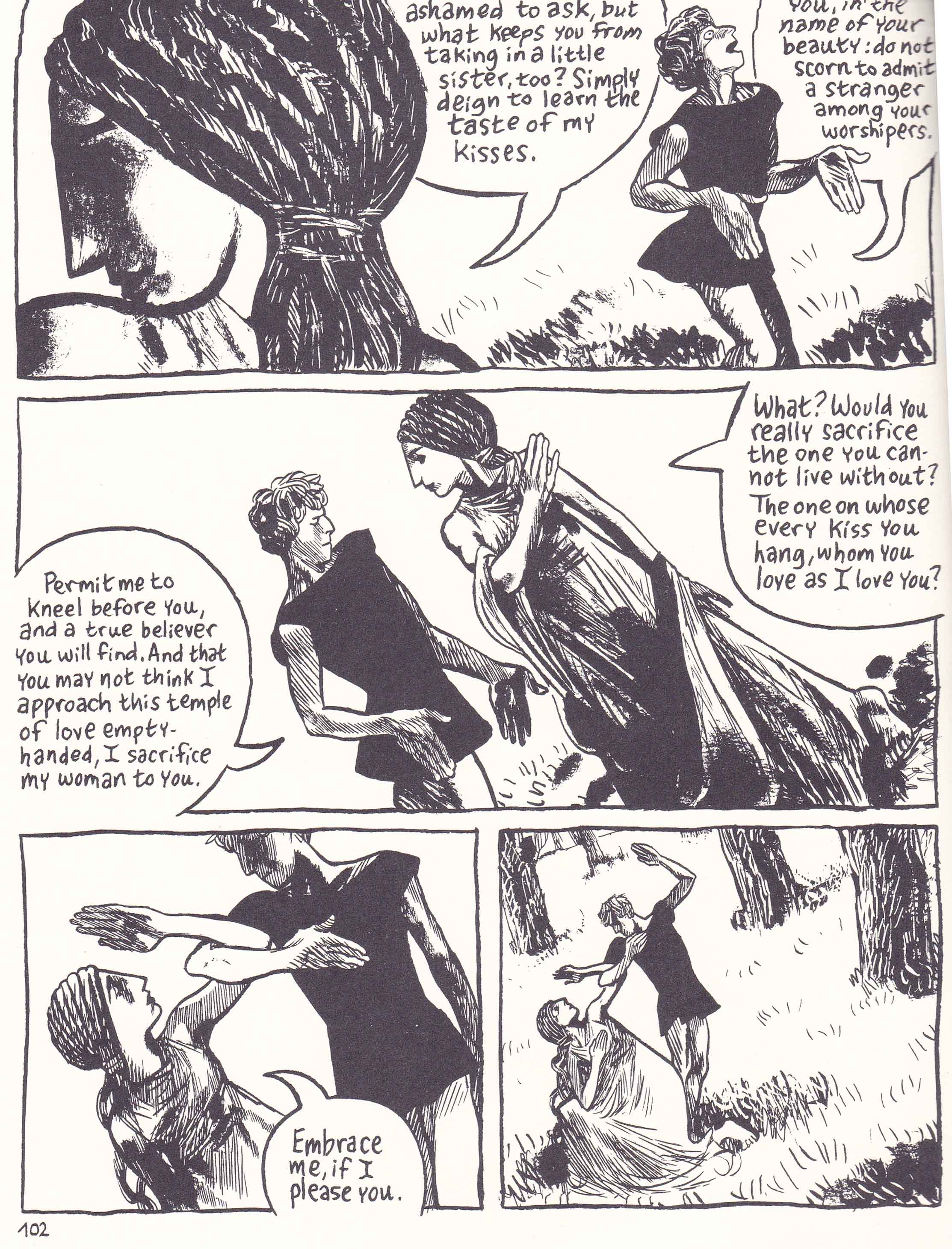

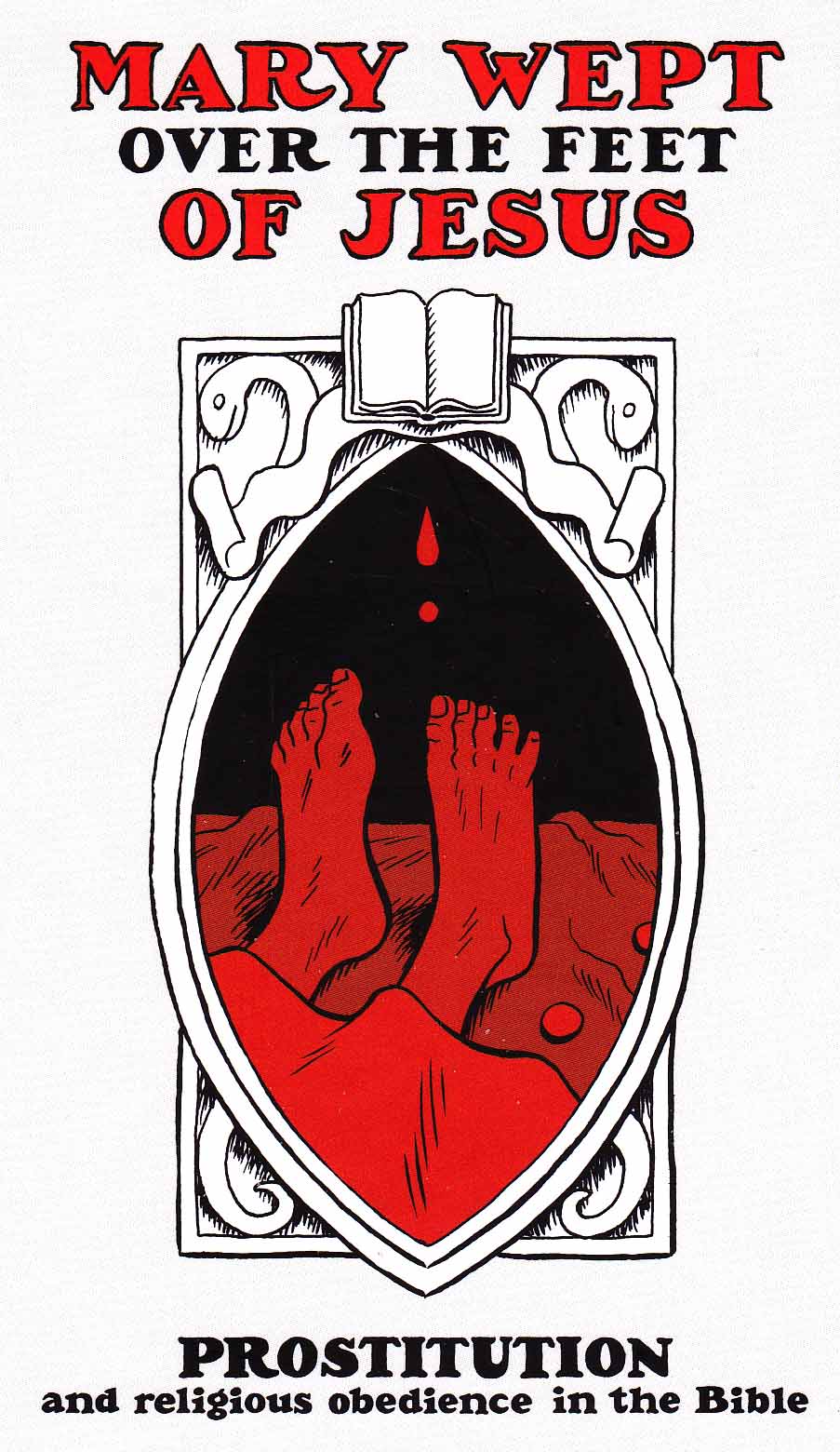

At the pivot point of chapters 5 and 6, Encolpius first finds his young Ganymede, Giton, before forsaking him for the illusion of his goddess (his Lady of Auxerre), a speechless statue (or human?) frozen against all reason and physical probability. Encolpius doggedly persists in his denial of the tangible world, its substances and its consequences: first interrupting a staged mythological performance of Theseus, Ariadne, and the Minotaur, killing the latter for his lack of grace on stage; then suffering impotence in the face of real physical (heterosexual) desire, any semblance of love thwarted by his idealization and greed.

This section constitutes Blutch’s main transcription from Petronius, namely Encolopius’ (impotent) encounter with Circe. From J. P. Sullivan’s translation of chapter 128 of Petronius’ Satyricon:

‘What is it?’ she said. ‘Does my mouth offend you in some way? Does my breath smell through not eating? Is it the unwashed sweat from my armpits? If it’s not any of these, am I to suppose you’re somehow frightened of Giton?’

Flushed with obvious embarrassment, I even lost whatever virility I had. My whole body was limp, and I said:

‘Please, my queen, don’t add insults to my misery. I’ve been bewitched.’

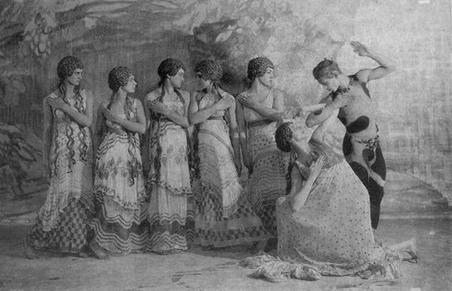

It is a loose adaptation but done with a kind of subtle commentary; for a number of panels have been lifted from old photographs of Nijinsky’s ballet for the Ballets Russes, The Afternoon of a Faun.

The ballet is inspired by the famous poem of the same name by Stéphane Mallarmé (L’Après-midi d’un faune, 1876) and imagines a dream-like state where the faun encounters two nymphs and cannot be entirely sure if they are real or imagined.

“I’d love to make them linger on, those nymphs.

So fair,

their frail incarnate, that it flutters in the air

drowsy with tousled slumbers.

Did I love a dream?

My doubt, hoard of old darkness, ends in a whole stream

of subtle branches which, remaining as the true

forests, show that I’ve offered myself (quite alone, too)

the roses’ ideal failing as something glorious––

Let me reflect . . .

what if these women you discuss,

faun, represent desires of your own fabulous senses!”

The faun, like Encolpius, is navigating the realms of reality and the purely intellectual, eroding the lines between both. In an article at the New York Times, Jeffrey M. Perl explains that his is a “search” for the:

”…distinction between real and imagined experiences…[…]… The skeptic faun has proof the nymphs existed—the love bite on his chest—but he mistakes proof for a mystery. The faun’s doubt about his afternoon has become the real experience. The creations of the mind, like poetry, exist.”

Unlike the faun of Mallarmé’s poem who remains at rest, wandering in his imagination undecided and unresolved, the protagonist of Peplum, the false Publius Cimber, exchanges the reality of his pederastic love for the fantasy of an unattainable goddess—a desire so absolute that he ignores the gold and precious stones in the treasure house where this goddess is stored, a delusion so captivating that all other encounters are rendered sterile.

What follows is Encolpius’ capture, unmasking as a false Publius Cimber and torture.

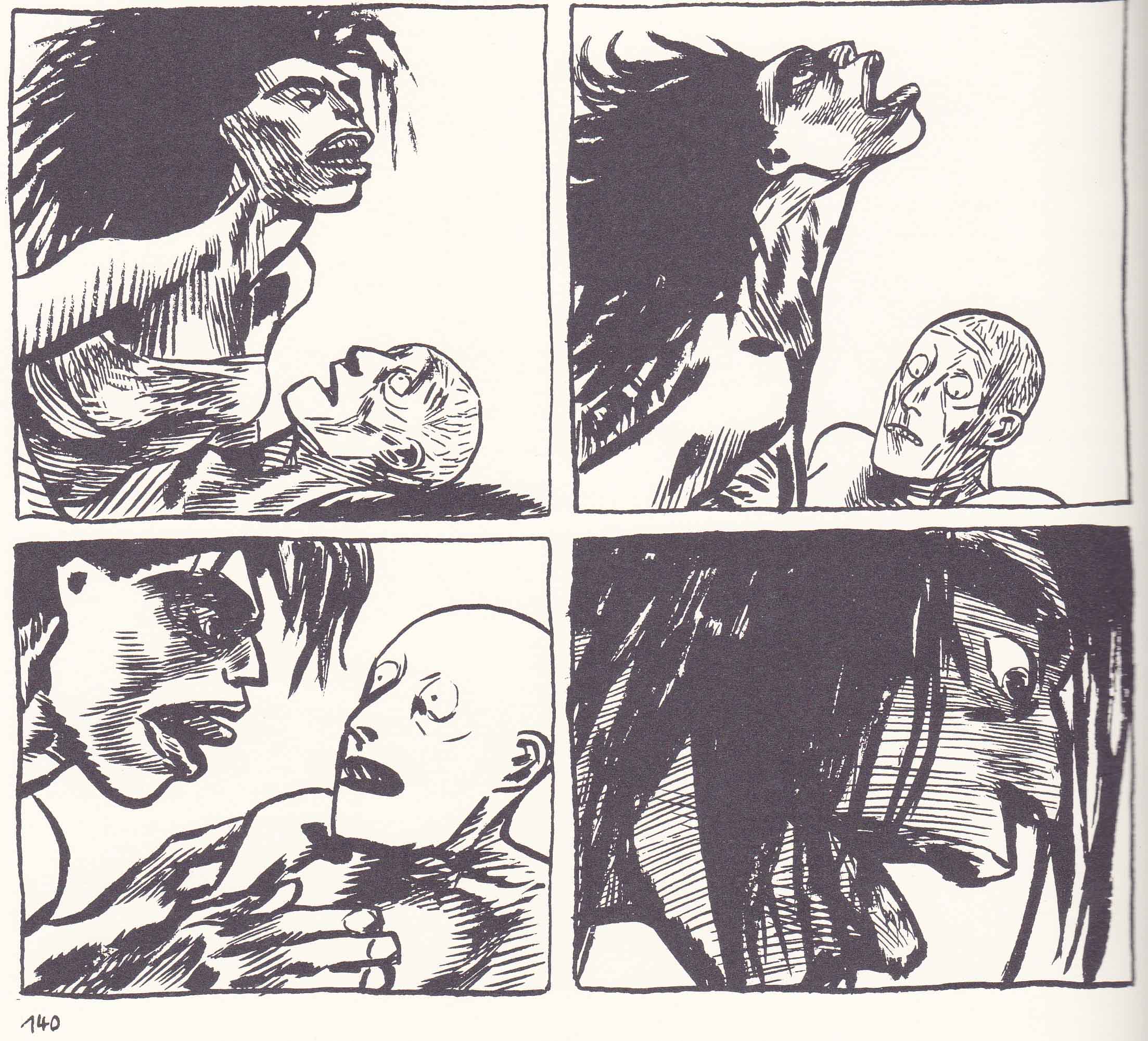

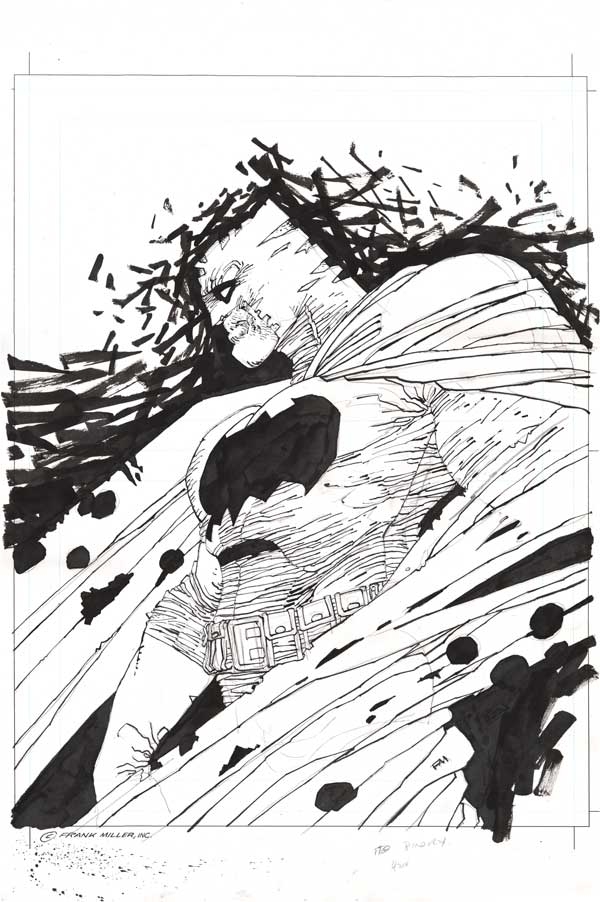

Then somehow miraculously the ship sinks and he is cast upon an island where he immediately faces a life and death struggle with a blood thirsty ravenous woman who he promptly cuts down.

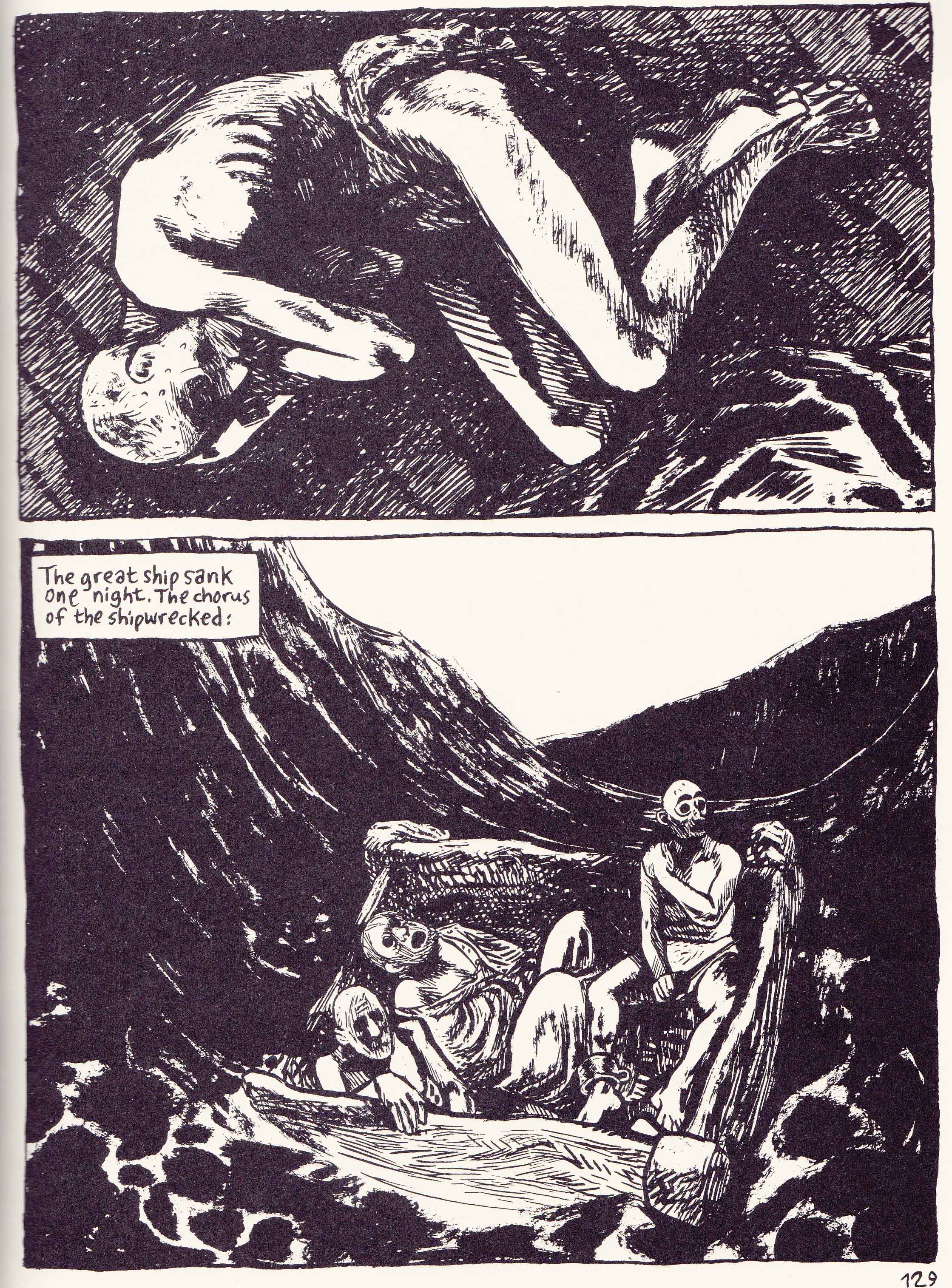

But not is all as it seems. Consider the fact that the protagonist is last seen in chapter 8 with his eyes gouged out and is then seen lying in the hold of the ship in painful slumber before a caption enigmatically states that:

“The great ship sank one night. The chorus of the shipwrecked.”

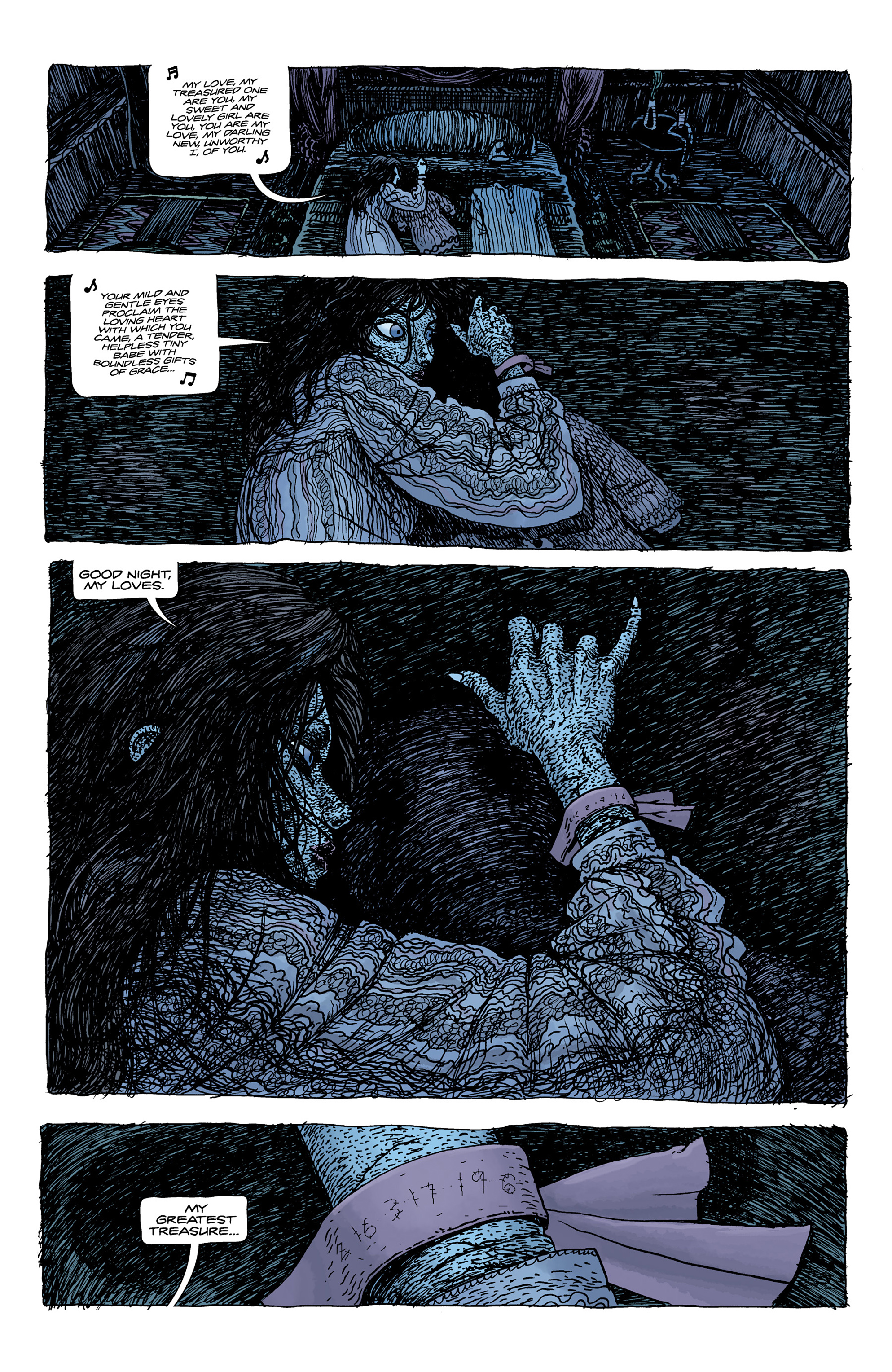

Why then are his eyes suddenly restored even as he lies in the bottom of a small boat (a ship of fools) rowed by an equally blind Charon mercifully dispatching his compatriots with a knife. It is almost as if Encolpius has to be blinded before he can truly see. Is all that follows merely a specter before death? Has he finally arrived at the end of his travels on an isle of the dead, an Elysium where his one wish, his one desire for a reunion with his goddess is fulfilled and shown to be absolutely corrupt and extinct? And is this land of the dead merely the one which most of us take for that of the living? This is by no means a happy or desirable end; this awakening from a pliable and abstract slumber to a haggard reality.

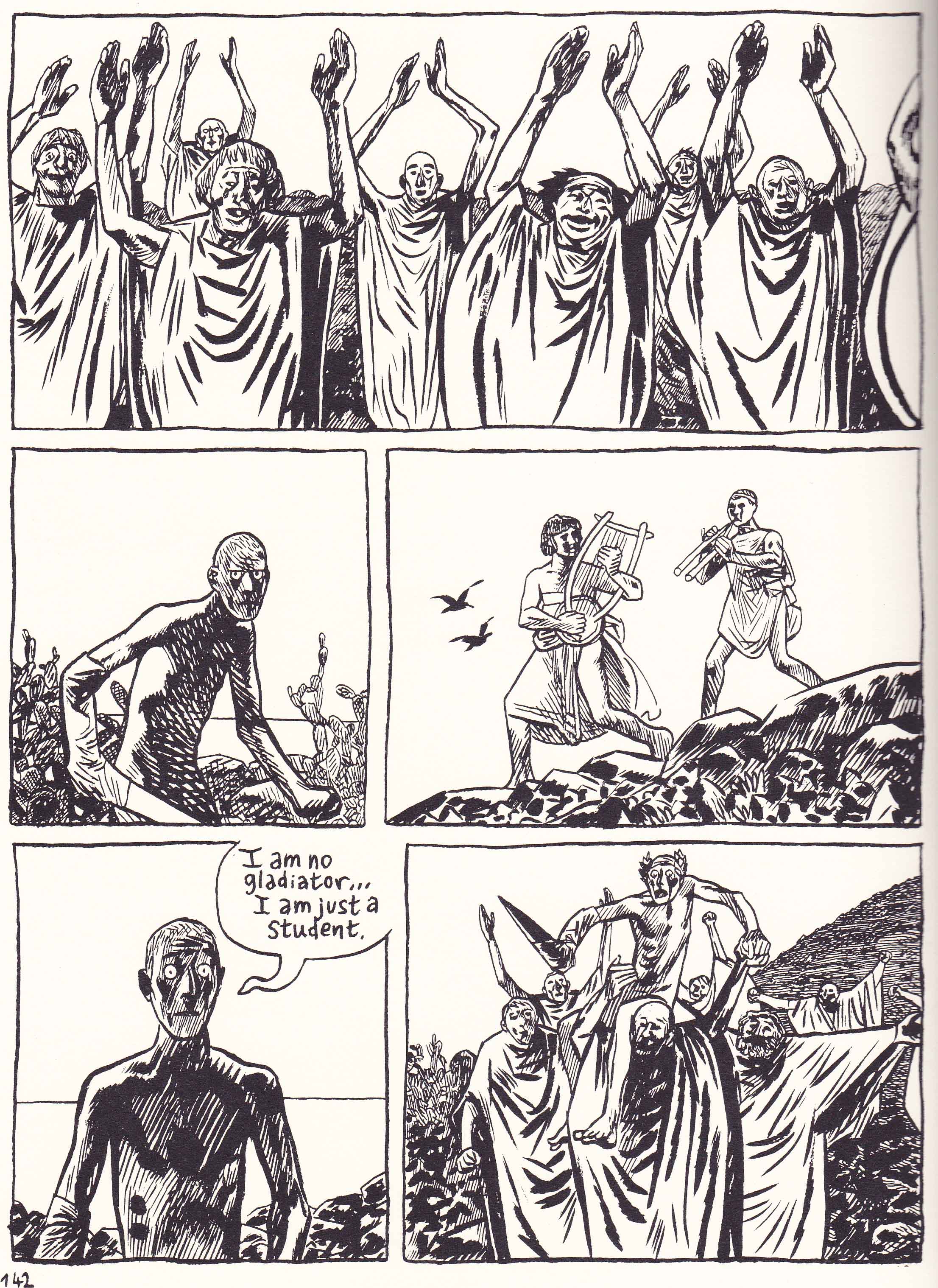

And here is where the comic’s chiastic structure lends additional meaning to the proceedings. Where the performance of Julius Caesar’s assassination was greeted with the silence of the murderers and readers at the start of Peplum, the gladiatorial might of Encolpius against the ghastly apparition of death is heralded with a laurel wreath and acclaim despite his protestations—he is the new champion and Caesar of this nether world, his face scarred with the shadowy countenance of brutality and revelation.

Writing at TCJ.com, Sarah Horrocks sees the central motif of Peplum as being that of surviving “the after-effects of an encounter with sublime beauty”:

“The question of how to negotiate desire in the face of the thing which destroys all other desires; how to live after seeing death–this is the panic that terrifies Peplum’s central protagonist…[…]… He has seen part of God’s face, and been driven mad by her…When finally his goddess abandons the mortal plane and assumes her shape as abject corpse, Encolpius has been deranged into this dark strange howl of a man who answers humor with horror. If in the presence of the divine he was rendered into infantile psychopathy, in its absence he has become the demonic knowing man, suffused with the horror of living.”

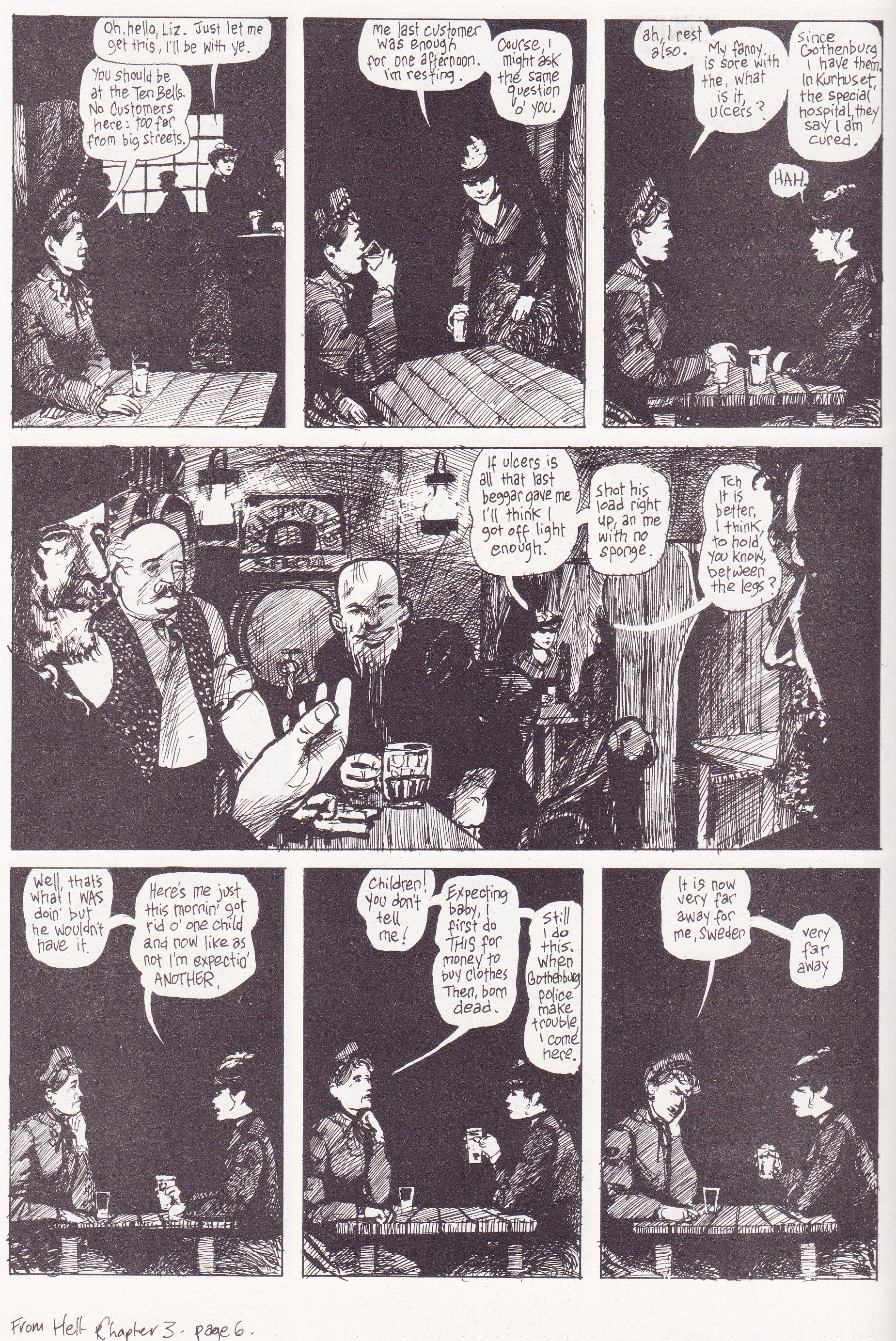

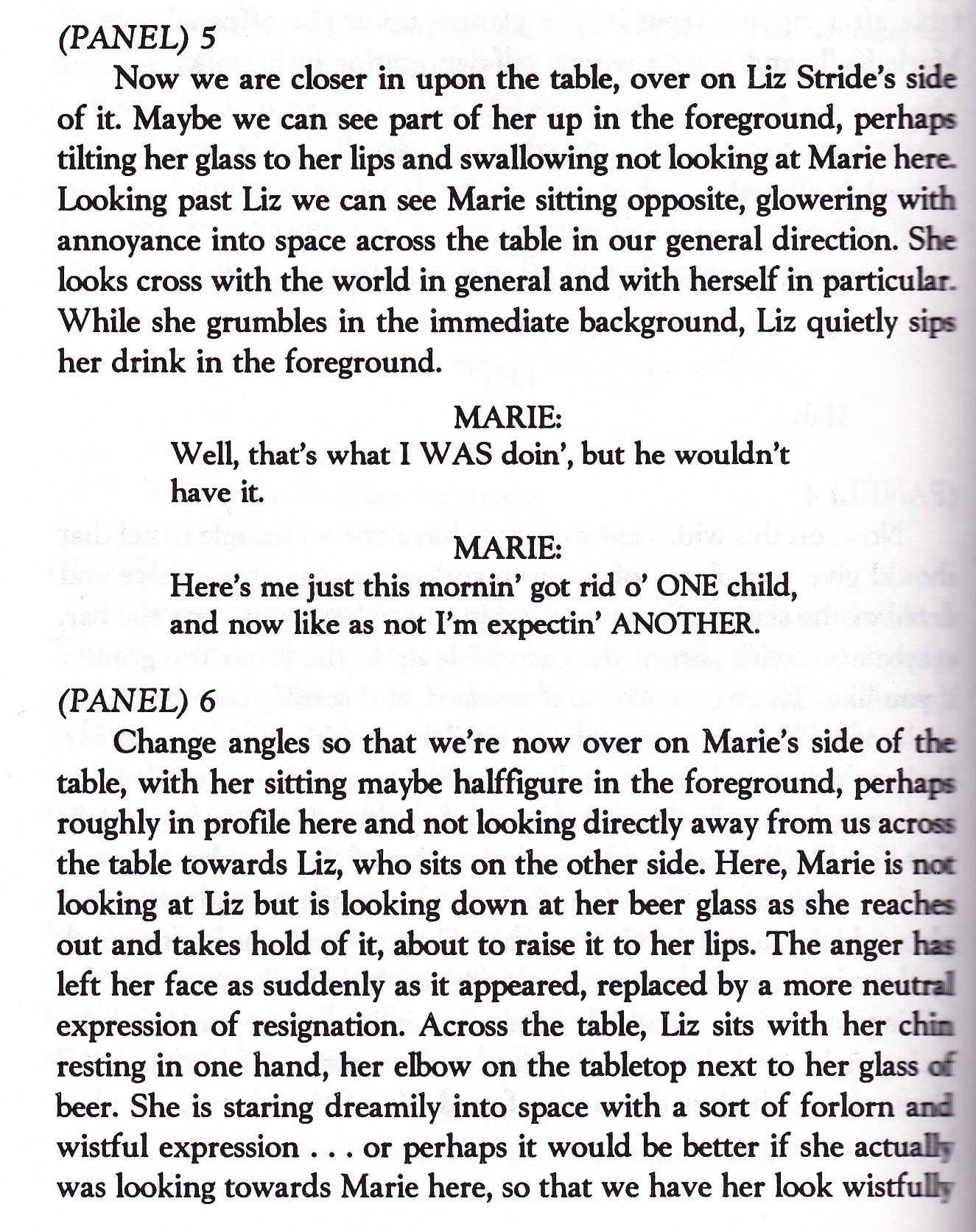

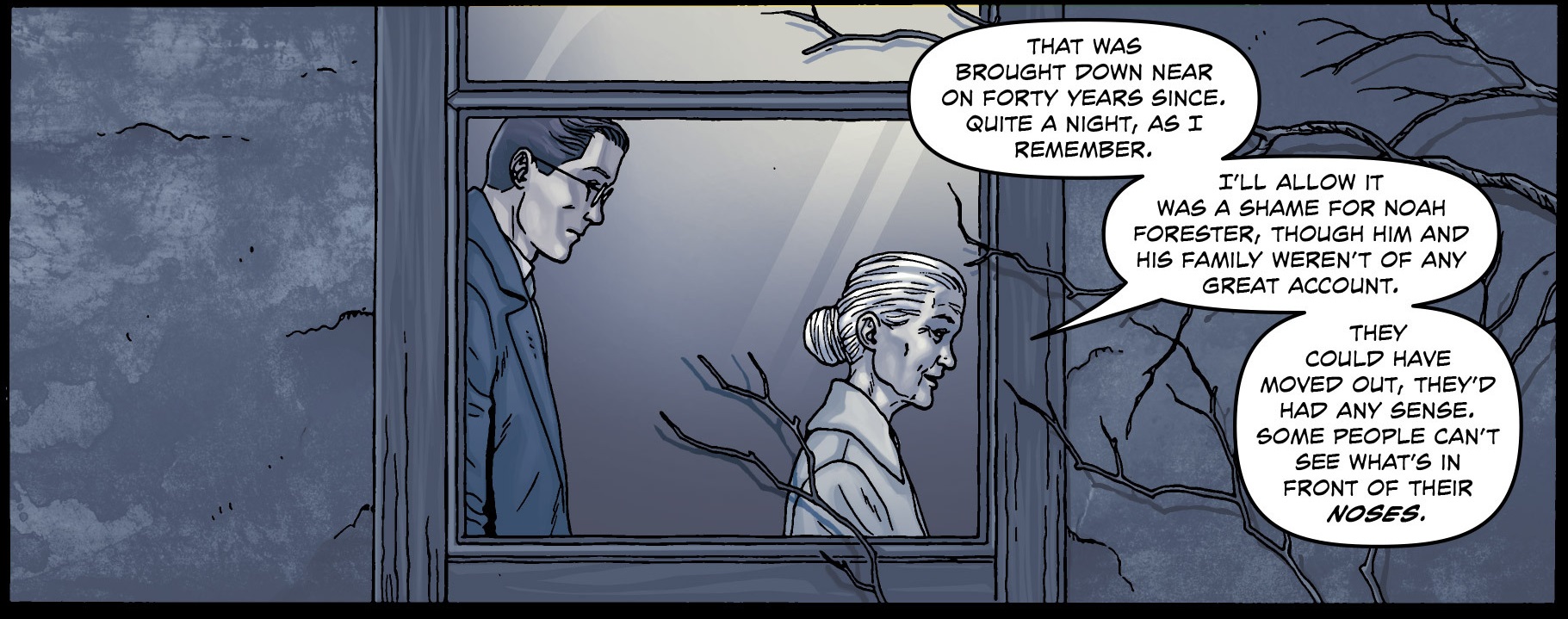

One of Ryan Holmberg’s complaints in the bellicose comments section of Horrocks’ review is that Blutch’s comic revels in its vulgarity and the deplorable view that serious works of art should engage in the sheer sordidness of life:

“It felt like skimming across the surface of cliches of “edginess,” accentuated with moody brushwork and smudges, without taking anything too far too any extreme to break with good taste…[…]…I think this graphic novel participates in that common move, where representations of evil are automatically taken as more authentic than representations of good, where death and violence are seen as more real, where shock is used (or attempted to be used) as a substitute for more subtle thinking about a subject.”

This thesis is worth considering.

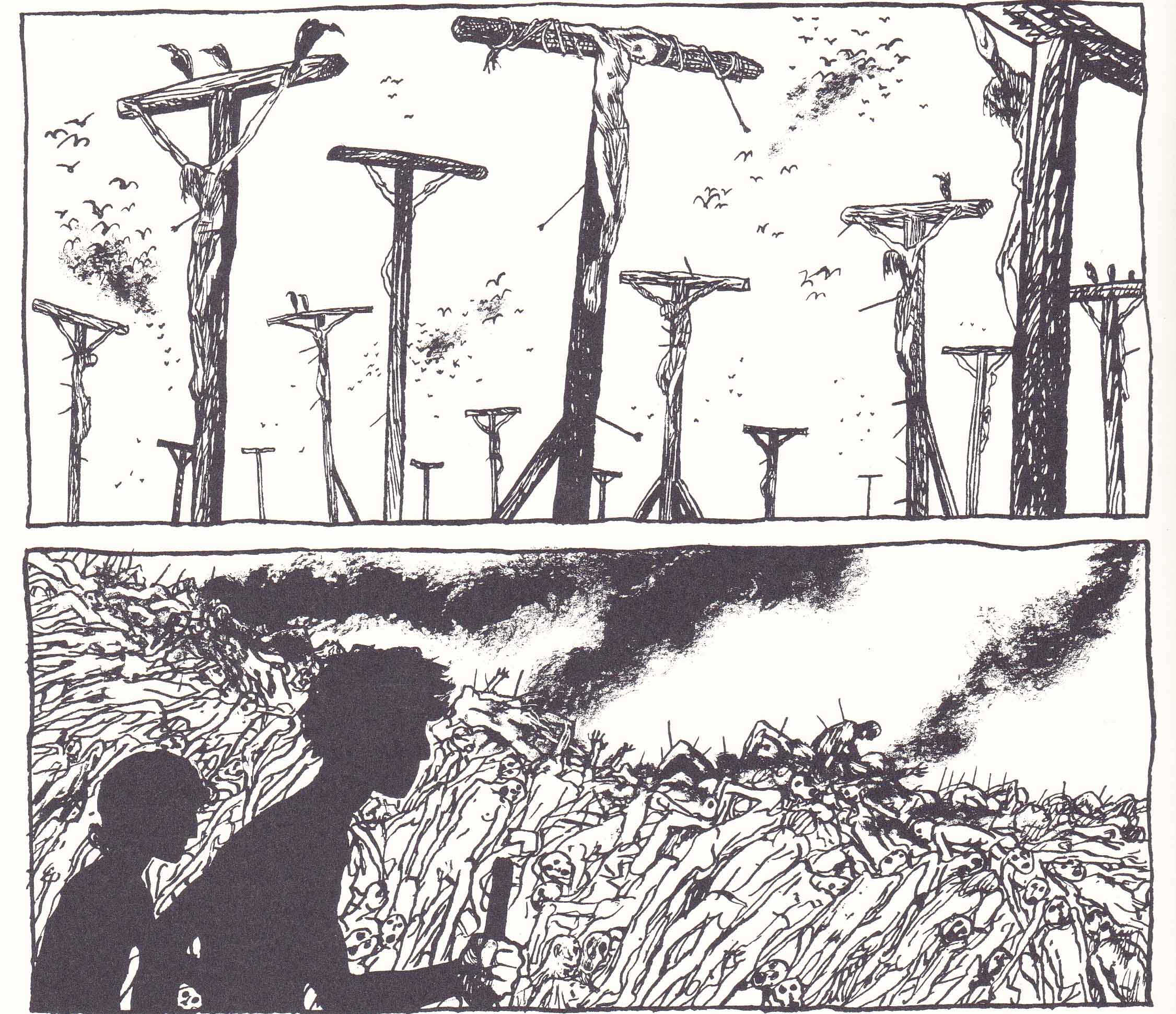

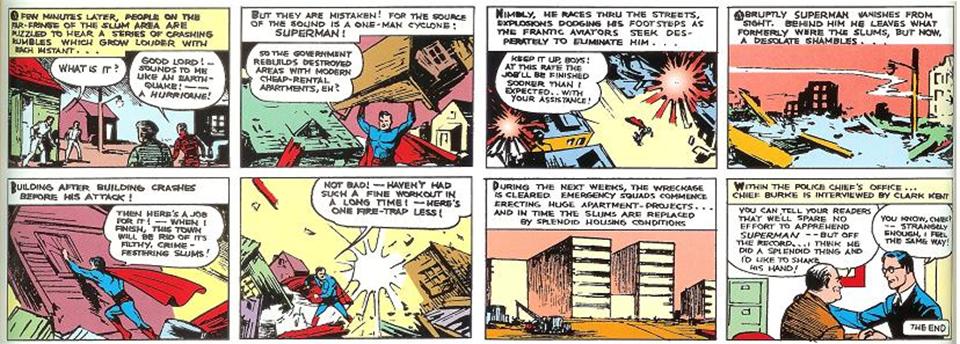

At one level, it does seem that Blutch is providing a counterpoint to the light-hearted easy heroics of the pepla (that strangely bloodless yet epic world of the ancient Romans) as well as the bizarre sexual antics of the Satyricon (or even Apuleius’ The Golden Ass). What we get are intermittent injections of violence and the fruits of violence, the bestial nature of the ancient world.

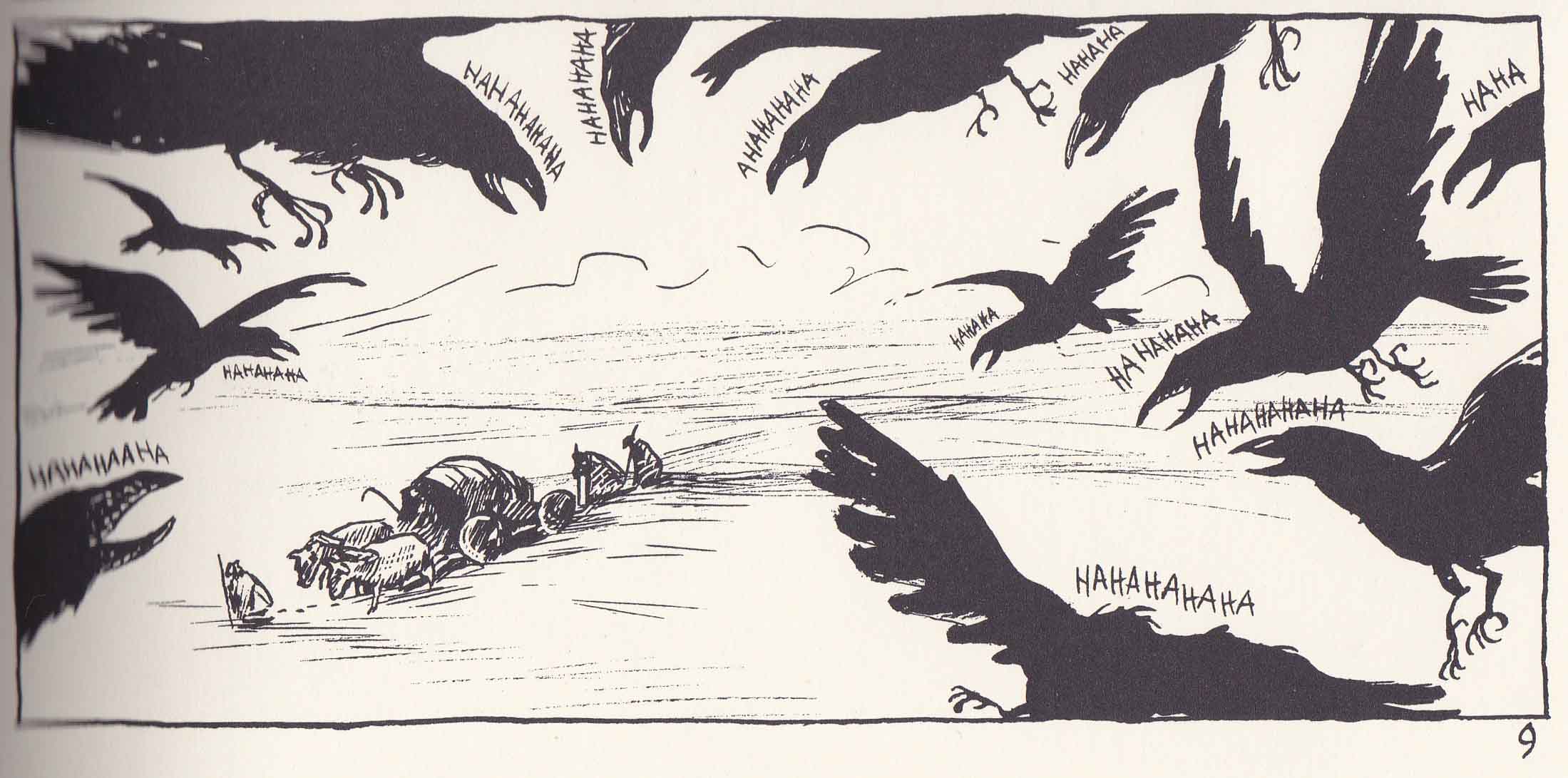

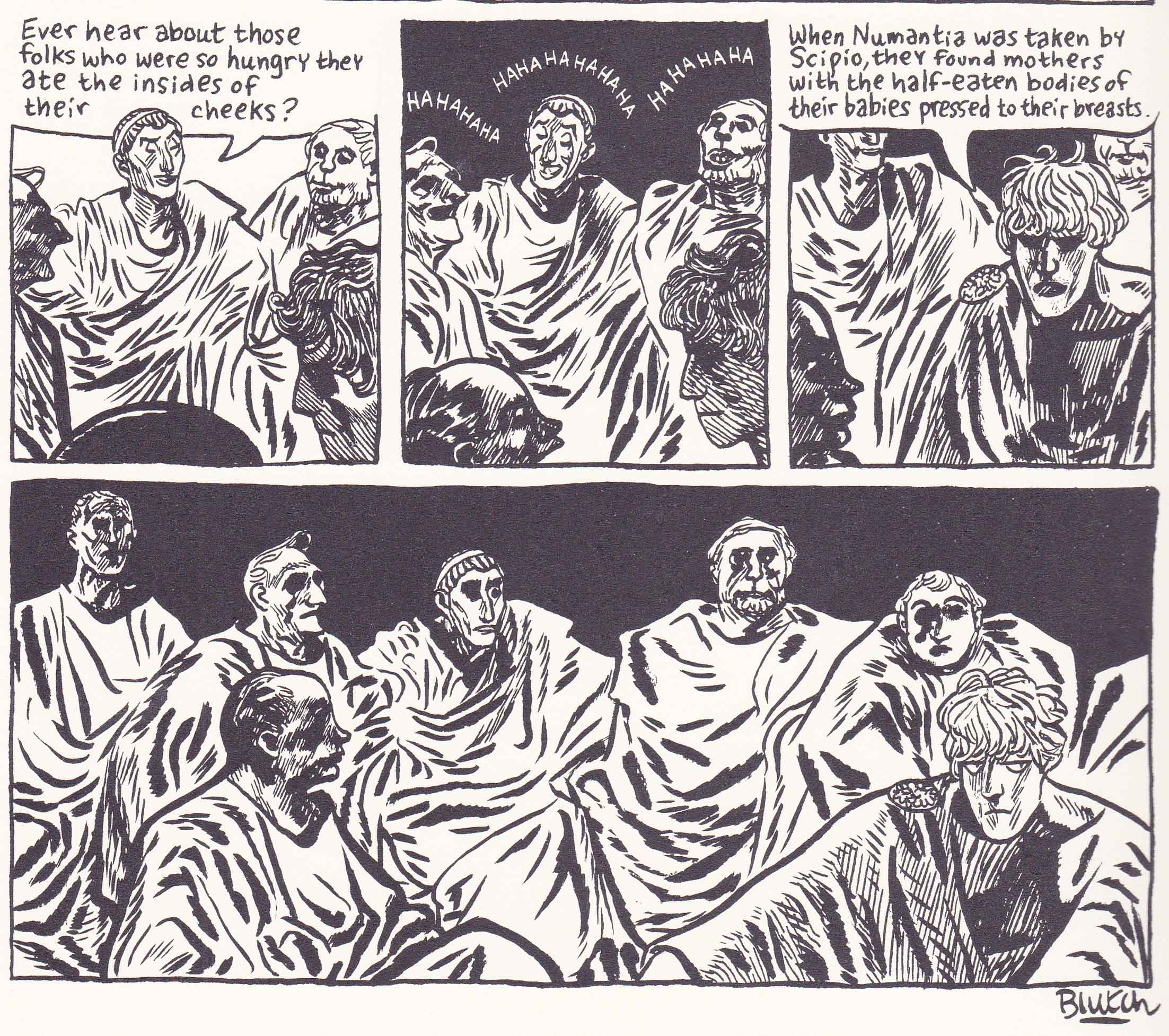

Yet there is little sense that this comparison is taken lightly, or that it dismisses hallucinatory fantasy or the pleasures that can be taken from idealistic art or lighter fare. The audience in Peplum seems to be constantly amused by the antics of Blutch’s hero: from the crows which greet Encolpius and the grave robbers in the first chapter.

…to the strange children hiding in the trees of the barbaric hinterland. There are the thoroughly amused city dwellers watching a mythological play, Giton giggling as he watches his lover murder a cave dweller with absolute callousness; and the exuberant witnesses of Encolpius’ gladiatorial exploits on the isle of the dead—all of them laughing and applauding for seemingly aberrant yet mystical reasons (is this a kind of “sublime laughter”; the knowing chuckles of those who see the complex whole).

The protagonist’s longing for an eternal untarnished beauty is shunned and ridiculed throughout the text but his final act of violence (after a string of atrocities) is greeted with a kind of ironic acclaim which he rejects. There is the sense that the protagonist consistently engages in acts of violence to protect his own avarice, his own sense of what is of eternal worth; like an artist depicting these things without reflecting on their real world counterparts. Blutch is a glorious artist and the inhumanity he depicts so utterly adroit that we can often quite easily suspend the apprehension of its horrors.

Is this a limitation in the artist or a limitation in the art? It might be said that Encolpius’ coupling with the wild woman at the tail end of the comic is more feral, more terrible, and more ugly then the slaughter depicted above; if only because he faces this head on and not as a background to his own avarice; his shaved head suggesting that he has joined his compatriots in the charnel house. In this way at least, Peplum is as much a meditation on the practice of art (its difficulties, dilemmas, and temptations) as it is one centered on artistic influence and aporia.

Yet the final state of the protagonist is hardly one to be desired; now firmly residing in the dour reality of unmitigated brutality, lost to the black humor of life. It is as if both the protagonist (the artist and performer of this strange world) had lost the power to see. And that, in one sense, is the “meaning” of Blutch’s epilogue.

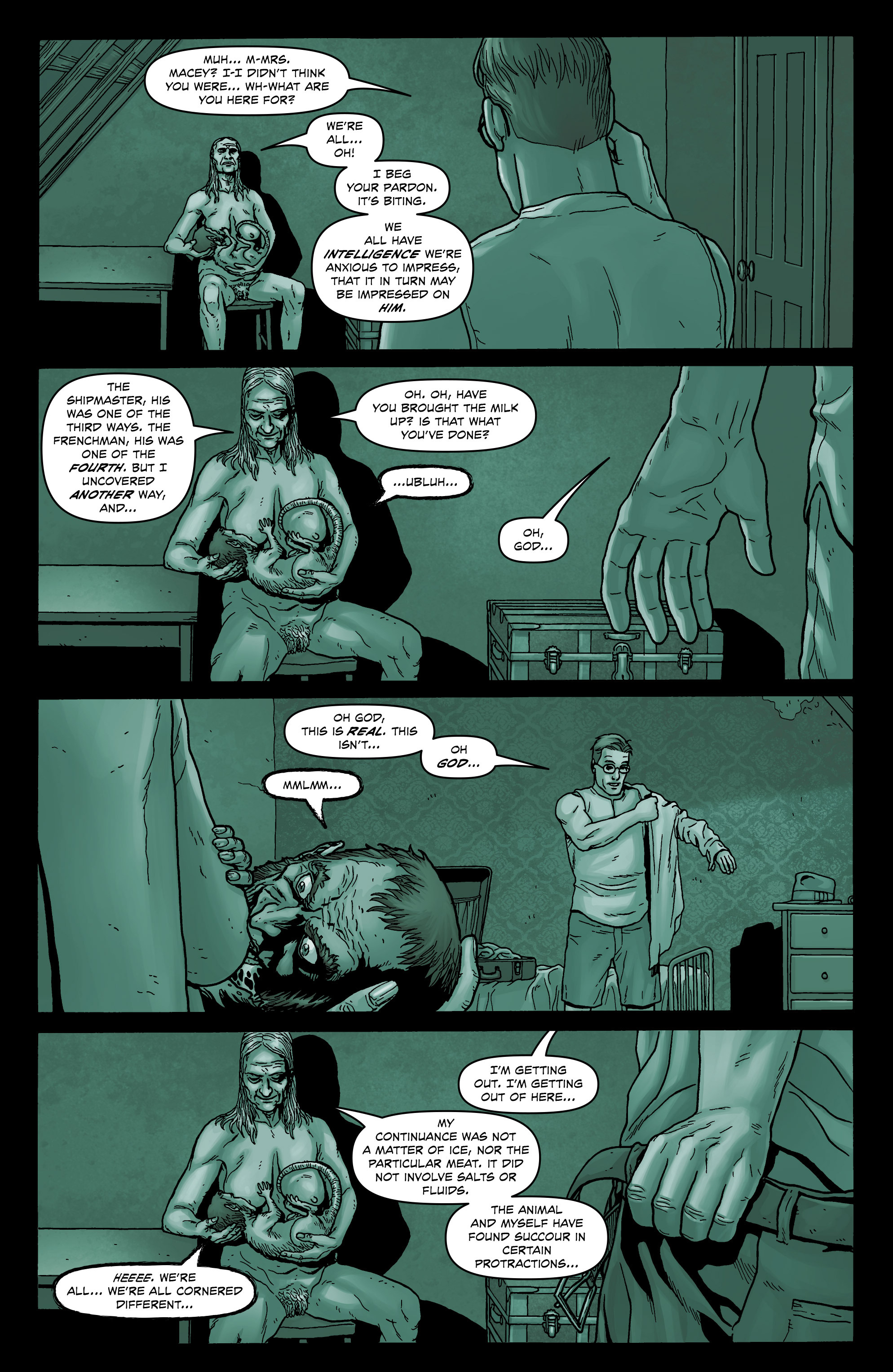

The revelers and storytellers of this latter day Satyricon are gathered in a large space telling tall, humorous tales of human misconduct (are the stories of Peplum the stories they have told?). The secluded villa of their congress is shrouded in the savage inking of darkest night. Their sublime laughter like the birds, children, and Giton before them resounding through the halls. One storyteller speaks of “folks who were so hungry they ate the insides of their cheeks.” The protagonist can only talk sullenly of mothers with half eaten babies clutched to their breasts.

This is the final line of Petronius’ Satryicon, a story without an ending (the work is largely lost) given new meaning in Peplum. Encolpius’ mastery of death and reality seems to flow seamlessly into his insensitivity to pleasure, song and poetry. He has become the unwitting master of Hell.

____________

(1) From an interview with the artist conducted by Matt Madden:

“I adore Fellini Satyricon and I’ve watched it a bunch of times, but I made a decision not to look at it while I was working on Peplum. In fact, I had Orson Welles on my mind instead…[…]… I was especially looking at his low-budget Shakespearean films—Othello, The Chimes at Midnight—that he made with little money or resources. I love how economical he is in those films, those minimal sets, that whole aesthetic was really what I was after. I didn’t want a lavish epic. I wanted something simple…[…]… I really wanted it to feel like a B-movie.”

(2) Sarah Horrocks mentions Blutch’s interest in the “sublime image” and also Julia Kristeva writing’s on the same. So I thought I’d include a short section from Kristeva’s Power of Horror to refresh our memories:

“The ‘sublime’ object dissolves in the raptures of a bottomless memory. It is such a memory, which, from stopping point to stopping point, remembrance to remembrance, love to love, transfers that object to the refulgent point of the dazzlement in which I stray in order to be. As soon as I perceive it, as soon as I name it, the sublime triggers—it has always already triggered—a spree of perceptions and words that expands memory boundlessly. I then forget the point of departure and find myself removed to a secondary universe, set off from the one where ‘I’ am— delight and loss.”