In her article on Graphic Journalism, Erin Polgreen states that:

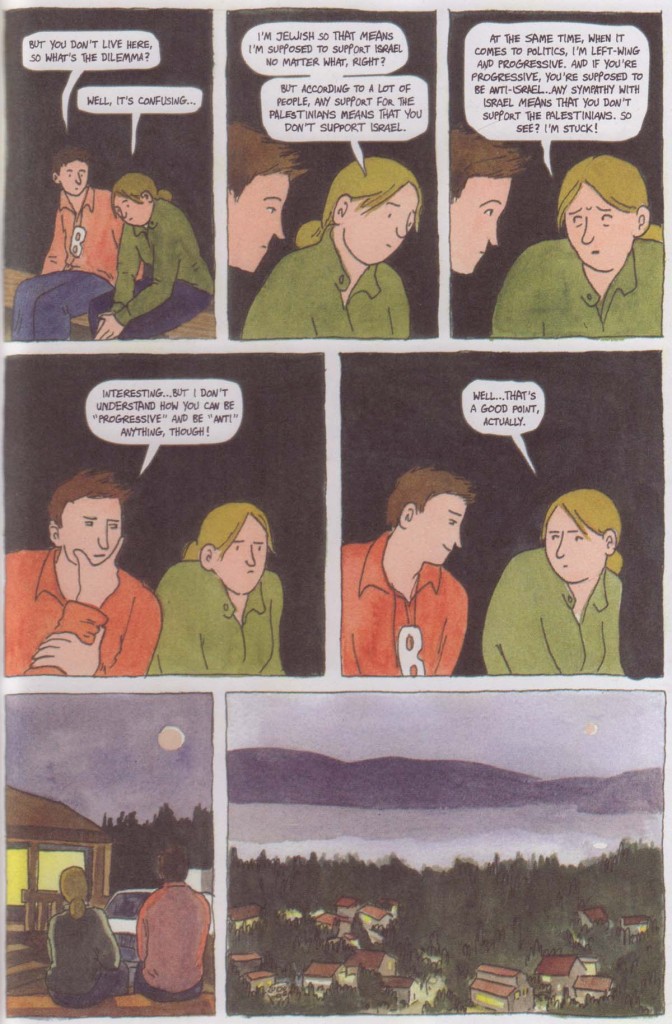

“[Travelogues] are often meditative explorations of a foreign landscape in which the reader unpacks their cultural baggage with the author, exploring a strange land with them. The key here is in viewer identification: The comics creator has a strong voice leading the narrative, and we trust them to impart facts and dissect stereotypes for us. Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less is a near flawless example of the travelogue. Glidden isn’t going for an objective non-fiction work here, which can seem counter-intuitive to journalists. Rather, she’s looking to use her experiences as a lens for dissecting her own cultural (mis)perceptions and takes the reader along for the ride.” [Emphasis mine]

There are many words which come to mind when I think of Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, but “flawless” doesn’t even come close to capturing the essence of any of them.

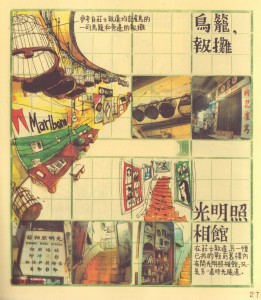

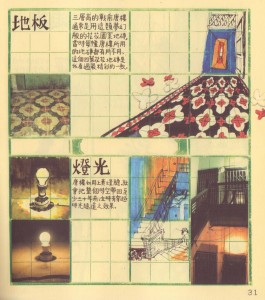

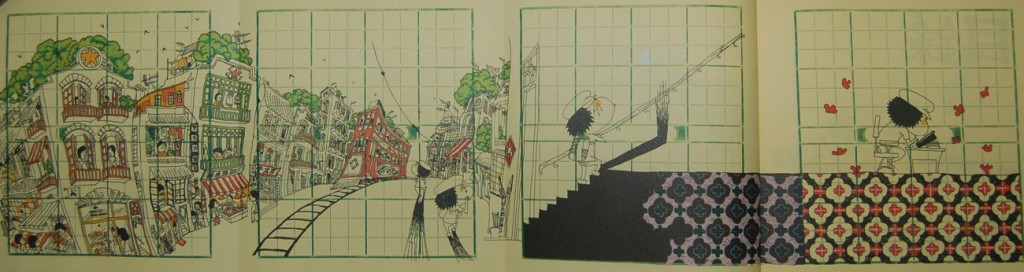

An overwhelming emptiness developed in my gut as I was reading this slim volume of tightly arranged panels depicting a young woman’s frankly insipid account of her first trip to Israel on a “Birthright Israel” tour. Glidden’s comic condenses the “promised land” into a series of flat, non-descript images and dialog sequences. Hence Masada becomes a mound of amorphous light brown soil, its history and controversies distilled to a shallow recital comparing the works of Josephus to her guide’s Zionist spiel. Would that she had read better books and developed a better mind for such analysis.

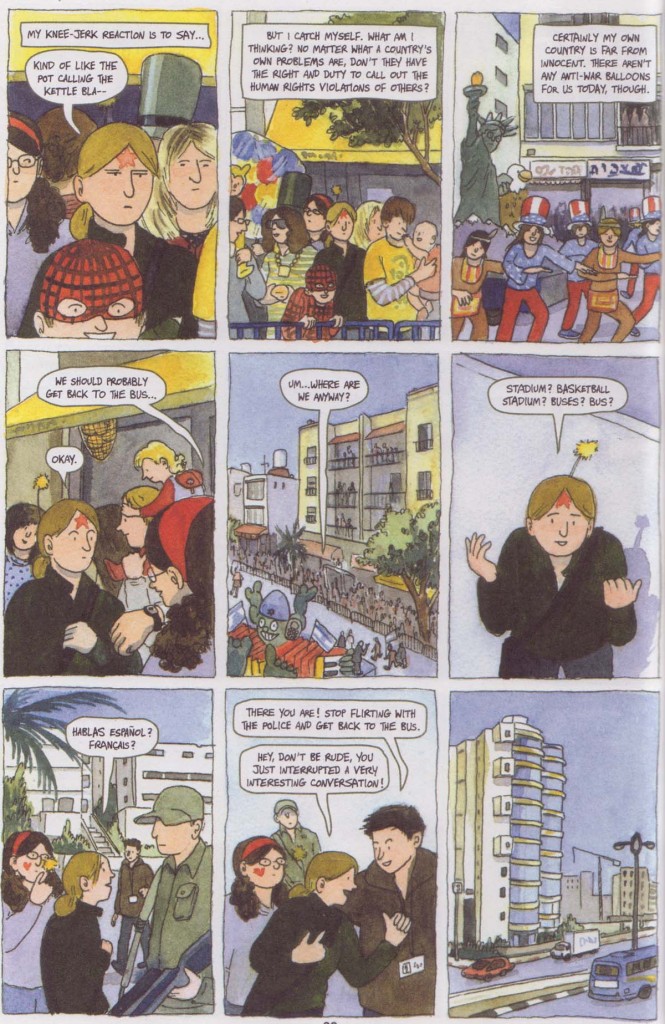

Where Matisse once suggested that “one square centimeter of any blue is not as blue as a square meter of the same blue,” Glidden proposes that a systematic dabbing of color will do the trick. Her vistas are almost infallibly debased to non-entities. Here a village landscape becomes only a momentary pause — an empty space — and quite secondary to the dialog preceding it.

The following montage of a street parade has much the same problem, passing fleetingly before our eyes like a colleague’s holiday slideshow.

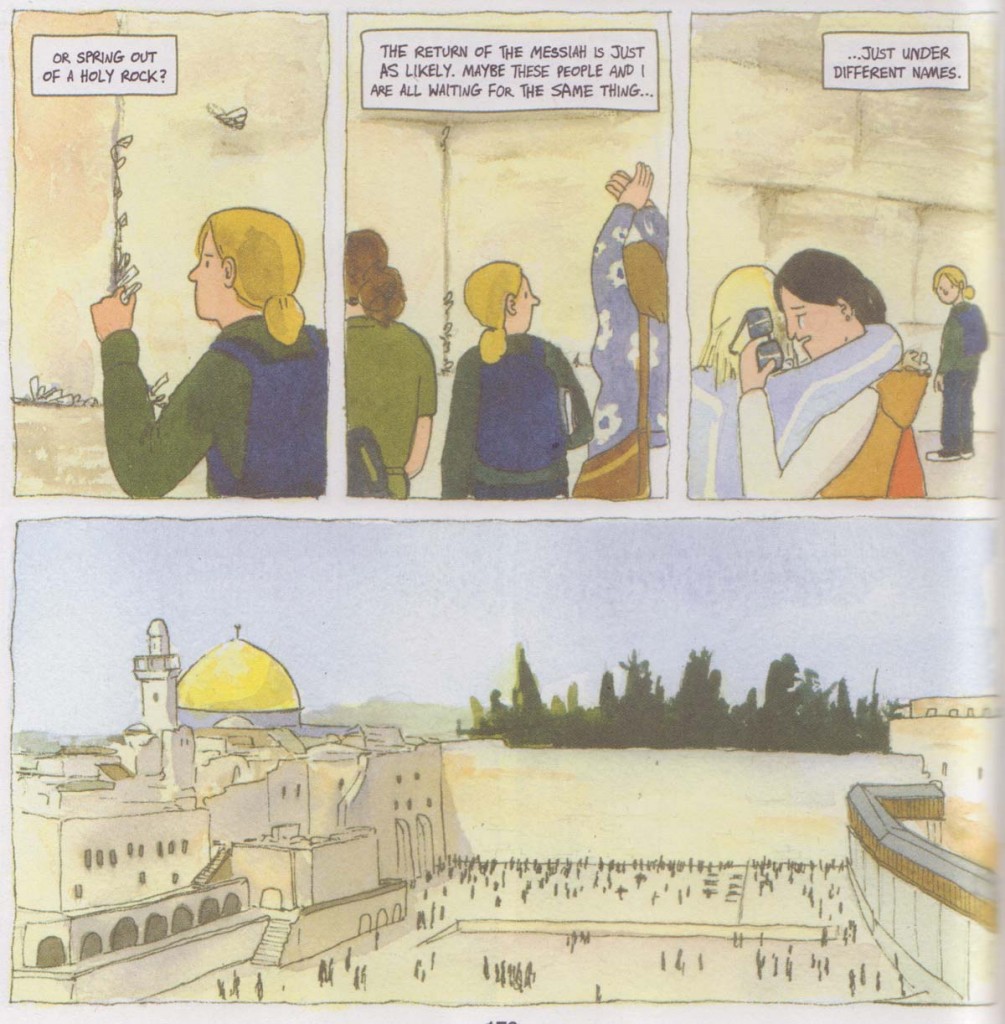

Only close to the Western Wall and the Dome of the Rock do we see a some recourse to the establishment of atmosphere and place, though still to somewhat hollow effect.

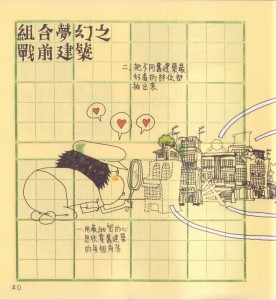

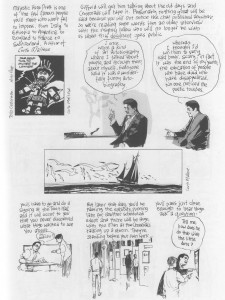

Once free of the strictures of the tour (and in the final chapter of the book), the cartooning which was once crudely serviceable begins to display a bit more polish, a dividend from weeks of practice and, perhaps, a process of trial and error. A more skillful practitioner might have used variations on the nine panel grid to engineer some points of conjunction and disjunction between text and image, but Glidden uses this device largely to preserve the steady voice of the storyteller and hence an effortless flow in her account. This is a hallmark of the plain narration advocated by autobiographical stalwarts like Harvey Pekar and his ilk. As such, Glidden’s authorial voice resides largely in her simple drawings and not in whatever talent she has for narrative or language.

What follows is a summation of Glidden’s entire experience (and conclusions) in the form of a series of conversations between the author and various people: citizens, both young and old, who have made Aliyah; a progressive rabbi delivering a message of reconciliation and calling for a striking of archaic laws from the Talmud; and, finally, an Israeli with whom she finds the peace to disagree. Those who have a place in their hearts for Glidden’s comic will undoubtedly point to these exchanges as the basis for their affection; the author’s heart always on her sleeve, her emotions ever on tap, her youthful idealism and barely formed intellect crushing all before her. This is a vision of comics journalism as a mediator for those who have little interest in reading.

I was about three quarters of the way through this comic before I realized that there was a fatal flaw in my approach to this comic. I was half expecting a travelogue in the tradition of Theroux if not Levi-Strauss. But the potential reader will need to reorient herself to the requirements of this cartoon journal for the best results. It is altogether more pleasing if one sees it as a self-lacerating memoir impaling the author’s younger and more foolish self (of course, Glidden recently celebrated the revolution in Egypt with all the superficiality of a 10 word Twitter missive, but I suppose that too could be seen as self-satire.)

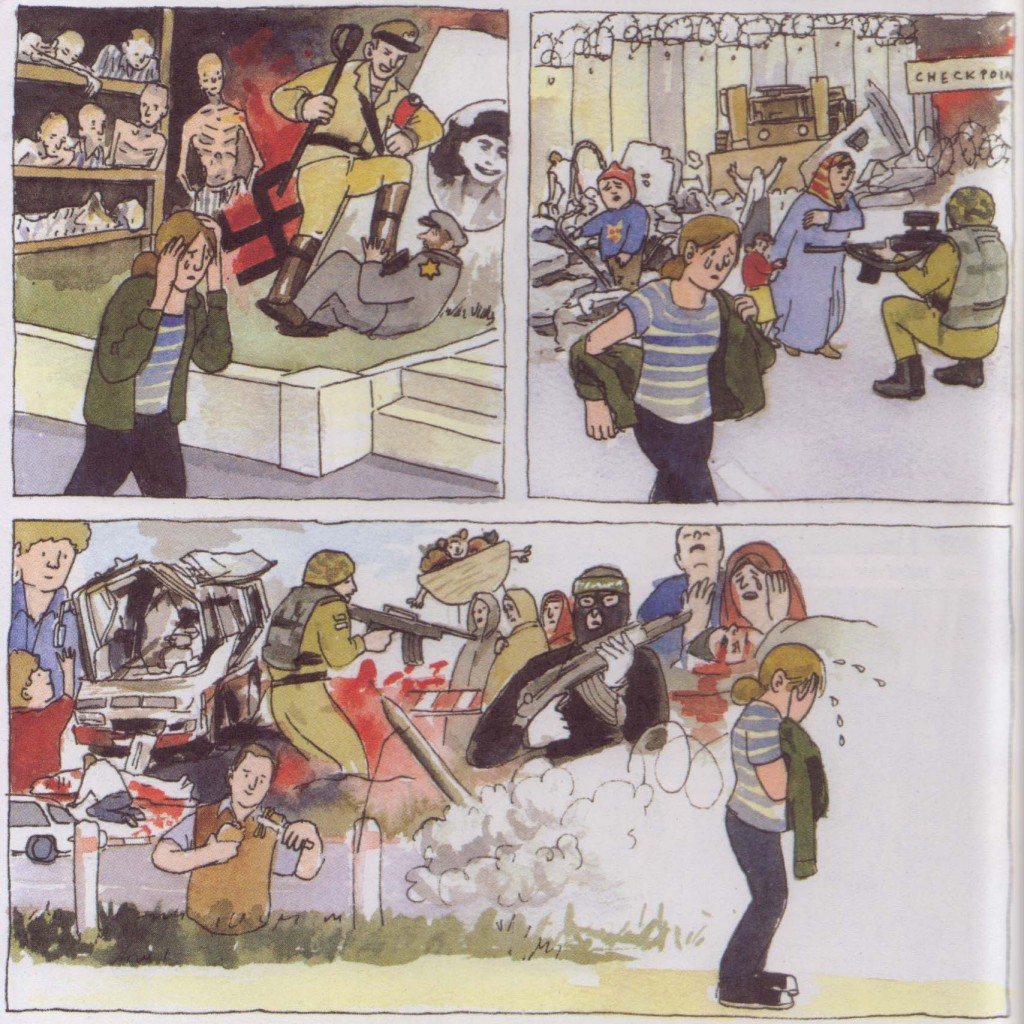

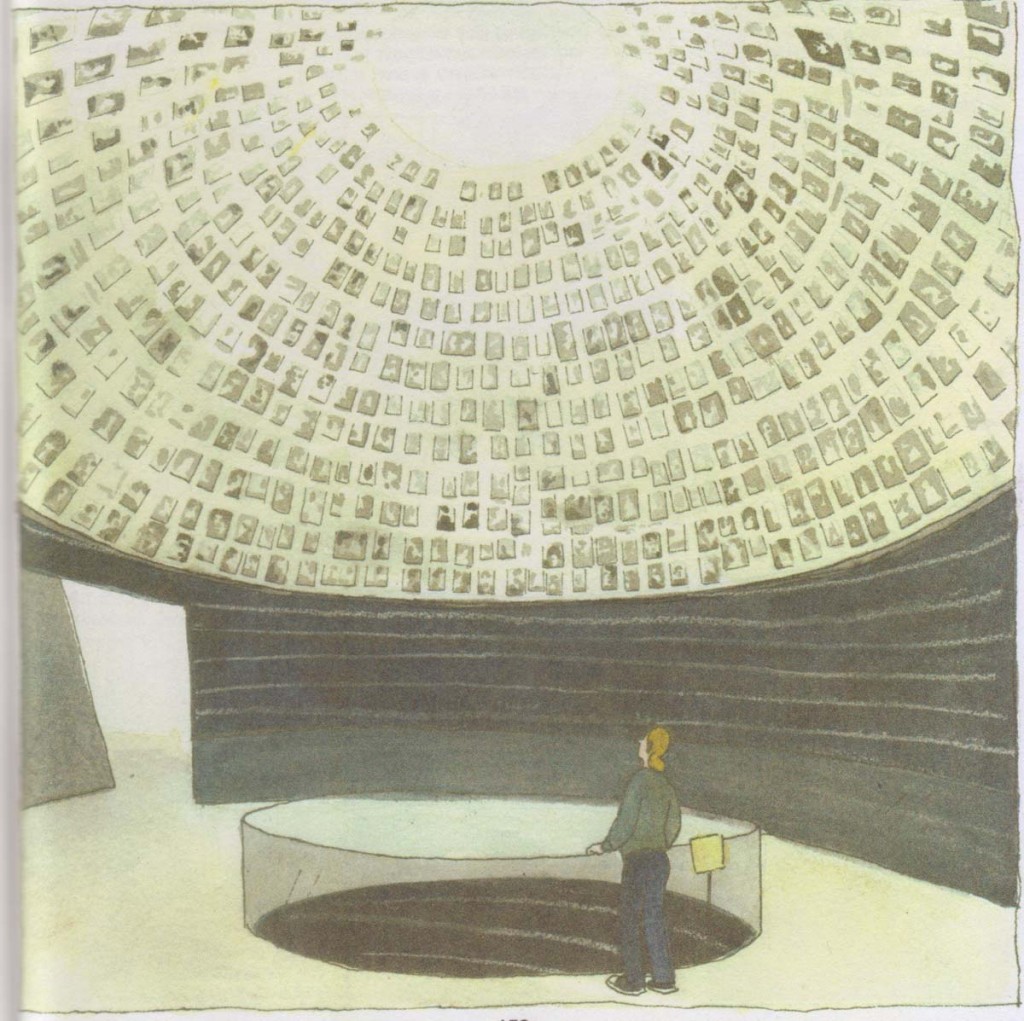

Nowhere is this more evident than in Glidden’s visit to Yad Vashem. The author is justifiably irritated by one of the more prevalent experiences you might find on a package tour — the headlong rush through a famous museum in order to get to a meal (or some shopping). Yad Vashem is quite naturally reduced to that complaint, probably a purposeful disclosure of her rather mean spirit at that point in time.

The guide’s voice becomes a consistent drone, and the sights and sounds of the Holocaust distilled into an understated bitching session.

When all is over and she is given some time to herself, a moment of tranquility in the Hall of Names; Glidden’s tribute to what the Holocaust experience is all about:

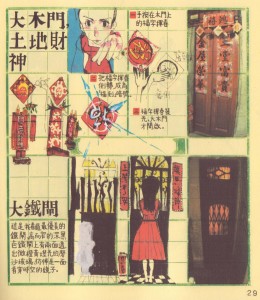

What lies beneath this is of course much more insidious and encapsulated in the following sequence of panels:

Here Glidden yearns for the “true” Holocaust experience; to connect and emote with the inhumanity dealt to some 6 million Jews — she wants to be that crying child in the group in front of her. Perhaps she wanted to be struck with awe at the incalculable evil and misery; to feel deep in her heart of hearts the tragedy of it all.

Like a friend who once told me eagerly about his tour of Auschwtiz, this is Yad Vashem as an amusement park ride; that all too familiar cry of, “What can I get out of it,” from cattle on a drive through unfamiliar territory. More damning than the reams of sexposès or masturbatory fantasies in the indy comics of the early 90s, for here Glidden reveals herself as a tourist and travel writer with absolutely nothing to say. That dullness captured in the ironic title of her book — How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less — for the creator knows full well that the country of her visitation is impossible to capture in that period of time. Glidden’s comic is a work of self-condemnation; a “warts and all” cautionary to all those who would seek to traffic in their trifling insights, for therein lies undistinguished banality. It is the rotting carcass of the autobiographical genre in comics.