Red Flowers. Sayako Kikuchi is lying in the shade of her tea shop. It is a warm summer day and far too hot to count the meager takings from the morning. There is the sound of cicadas in the background and we gaze up at this incessant activity with the girl. The tree before us is as firm and immovable as nature itself. The tea shop is cradled in its grasp, nestling in a womb-like clearing with tendrils and fruit running through its thatched roof.

Author Archives: Ng Suat Tong

Review: Josh Simmons’ House

In an interview given in conjunction with Archi et BD, la Ville Dessinée (see Alex Buchet’s post), Jean-Marc Thévenet suggests there is in many comics “a psychological pressure suffered by a hero who is more often than not dominated by the environment in which they live.” This is, perhaps, the most common manifestation of architecture in American comics.

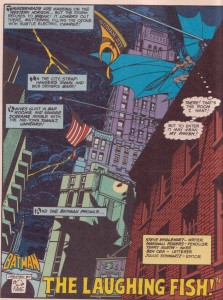

At a more popular and utilitarian level, we have Marshall Rogers’ delineation of the ornamented skyscrapers, alleyways, fire escapes and bricks that make up the borders of Batman’s Gotham, casting the caped crusader into realistic space, Rogers’ occasionally clumsy anatomy and staging notwithstanding.

Review: The Playwright

Warning: Spoilers Throughout

The latest comic by Eddie Campbell is conventional in a number of ways peculiar to the form. It is a collaboration with a writer, in this instance Daren White, the editor of the Australian anthology DeeVee. Also familiar is the presentation which is not dissimilar to what you might find in a newspaper strip collection with the panels laid out in single file across a squat rectangular book. The pages only lack the closing punchlines once deemed so necessary to such endeavors, but these occur frequently enough so as to negate any perceived differences; the temporary conclusions and logical ellipses between the pages being the very stuff of modernity (see Campbell’s remarks on the rearrangement of the strip from 9 panels per page to its current format in the interviews below).

A Response to Alan Choate’s Defense of R. Crumb’s Genesis

The Interview as Criticism: Gil Kane

“One cannot overstate how significant [Gil Kane’s] 1969 interview in Alter Ego(conducted by Benson) was to those of us floundering around trying to make some critical sense of comics. I’ve spoken to literally dozens of people over the years who read that interview when it was originally published and they all had pretty much the same reaction: Kane’s was a jaw-droppingly invigorating way of looking at comics. He took the only intelligent path a critical mind could given the comics he had to work with; he dismissed the scripting out of hand and focused on the distinctive but theretofore recondite visual virtues of specific artists. He articulated what many of us impressionistically loved about Jack Kirby and John Severin and Alex Toth but couldn’t put into words — or even into cohesive thought. He provided a ray of hope that comics could indeed be admired without abandoning one’s brains.” Gary Groth

“To be more concrete, some of the best comics criticism has come in the form of interviews done by artists like Gil Kane, Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman.” Jeet Heer

“FWIW, I also tend to agree with Jeet that, in practice, much of the best comics criticism has been through the interview form…just because of the history of comics criticism (which has been pretty spotty).” Eric B.

“I agree, Noah, but notice how much communication interference there continues to be: the assumptions that led to the interference in the original post go very deep. And they’re the same, deep assumptions that lead to the point you originally noticed: the valorization of interviews over analytic essays… The comments thread here has largely been about decoding the resistance to the ideas in both your original post and here, rather than decoding the ideas. Although I think your explication is indeed productive, I think the resistance is still pretty strong…this is a resistance deeply tied to nostalgia and to nostalgic identification — the “retrospective idealization” of the author or creator as the anchor and truth of meaning. That’s one thing you lose if you topple the interview from its pride of place. I think this is probably the mechanism by which the art comics subclique has managed to reproduce the dynamics of the larger superhero subculture: they’ve simply replaced the superhero with the Author, without actually disrupting the nostalgic relationship to the comic art form. That’s how you get the “fetishization of interviews” you reference in the original post.” Caro

Robert Crumb’s The Book of Genesis: A Reply to Alan Choate

This is a reply to some of Alan Choate’s comments on my original article on The Book of Genesis (see comments 52 to 58). Rest assured, this won’t disrupt the regular programming on HU.

Firstly, Alan, thanks for putting all these thoughts down. Given their length, you might have been better served by a proper blog entry rebutting my article but we’ll have to make do with what we have. My first instinct was to let your comments stand as a useful antidote to the ambivalence or sheer negativity you detect in my article. But allow me to take on a few of them if in haste:

A comment on Ken Parille’s discussion of Robert Crumb’s Genesis

Before I forget and these connections are lost in the mists of time, I just wanted to add a link to Ken Parille’s lucid explanation of the attractions of The Book of Genesis. Some notable excerpts:

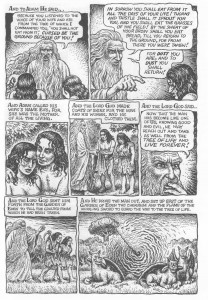

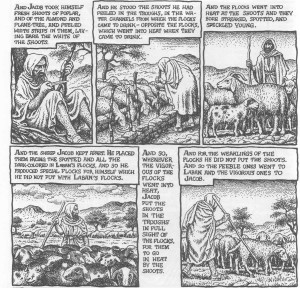

“The fundamental achievement of Crumb’s Genesis for me is that it avoids something that’s central to so many illustrated versions of the bible or representations of biblical scenes: Crumb rarely idealizes his subject matter. He is not creating an inspirational text, a magical text, or a sympathetic mythology — nor is he mocking the bible. The wonder of Crumb’s Genesis is not the unknowable wonder of God’s ways but of people’s actions as the bible recounts them. If there is reverence in Crumb’s work, it’s for the flesh, for the materiality, both ugly and beautiful (though more often ugly), of biblical characters and the things they do.”

” I feel a greater sympathy with Crumb’s strategy than I do with, say, Michelangelo’s. In its refusal to idealize, Crumb’s seems more ‘real’ to me. The thickness and gritty texture of Crumb’s line and character designs (thick legs, thick lips, thick fingers) tell a truth about the Book of Genesis obscured by more reverential approaches. (It’s almost as if the medium of cartooning is better than painting for this text . . .)”