“It’s even more mesmerizing simply because Sandell is a natural storyteller…Every page seems to scream, “See how easy it is to tell the truth? You just do it!” If only it were that simple…I fell in love with this book and its raw honesty. It’s gut-wrenching and compelling.” John Hogan, Graphic Novel Reporter

“We’ve had a really good summer for graphic novels, haven’t we? There’s universally well received work like THE HUNTER by Darwyn Cooke, and stuff that doesn’t seem to be on anyone’s radar, like THE IMPOSTOR’S DAUGHTER from Laurie Sandell (I thought it was a terrific little book!)…” Brian Hibbs, The Savage Critic(s)

“The Impostor’s Daughter is funny, frank, and absolutely engaging…” Susan Orlean, author of The Orchid Thief

“Sophisticated and spellbinding…The Impostor’s Daughter, is rife with dramatic family dynamics, secrets, and subterfuges….By uncovering the buried truths of [her father’s] past life, she claims her own coming-of-age story.” Elle

“In this delightfully composed graphic novel, journalist Sandell (Glamour) illustrates a touchingly youthful story about a daughter’s gushing love for her father. Using a winning mixture of straightforward comic-book illustrations with a first-person diarylike commentary,” Publisher’s Weekly Review

“I was very disappointed by The Impostor’s Daughter, because there’s a tremendous story in here, one that occasionally peeks through before being overwhelmed by a story about a spoiled girl who just needs to grow up. That she does eventually grow up doesn’t excuse the many events in her life that drive us nuts because of her immaturity. I’m not sorry that I bought it, because a lot of it is fairly interesting, but Sandell never gets below the surface of any of her characters, including, to a degree, herself, and that means the book is ultimately unfulfilling. When your journey to maturation is spurred on by Ashley Judd, as it is in the comic, I find it a bit shallow. That could just be me, though.”

Greg Burgas, Comic Book Resources

“Frankly I think it is just you. Loved it. Think it is an amazing, honest, well written memoir. Looking forward to her next book.” – “Mandy” in reply to Burgas’ review

_______________________________________

The synopsis provided on the inside flaps of Laurie Sandell’s comic provide as good a summary as any with regards the contents of The Impostor’s Daughter:

The Impostor’s Daughter begins with a relatively sedate depiction of Sandell’s childhood: a mixture of parental awe and familial tensions.

The publisher’s synopsis, however, prevents any easy acceptance of this largely idyllic childhood. A fifth of the way into the book, we see the cracks appearing in the form of some credit card fraud and broken confidences on the part of Sandell’s father. He remains largely unrepentant to the end despite his acquiescence to the truth with regards his path of destruction through his gullible friends and relatives.

The rest of Sandell’s book is a kind of psychotherapeutic journey of soul baring and self-analysis. We see her searching for her identity through a host of jobs and self-destructive relationships in various countries. The gradual realization of her father’s deceptions and lies fuels her own depression and Ambien (Zolpidem) addiction. Sandell finally finds a path to inner peace via some psychiatric advice from Ashley Judd and her self-admission to Shades of Hope Treatment Center in the closing pages of the book.

Greg Burgas’ negative review of Sandell’s book is instructive because it highlights a particular emotional critical approach. He is annoyed by Sandell’s seeming immaturity well past the age of 30, her clichéd depiction of one of her long term relationships and the needlessly ruinous course of her early life (pills, alcohol and idol worship). In short, he finds the narrative uninspiring and the character depicted therein unsympathetic. The latter aspect, of course, has little bearing on the quality of the final work for there have been many fine works of art depicting the most fatuous and despicable characters ever imagined.

Burgas is not incorrect in pointing out Sandell’s fondness for celebrities and what comes across as self-satisfied preening in front of her readers earlier in the book (as she chalks up interviews with various stars). The nature of Sandell’s day job, of course, virtually necessitates such a relationship.

One of Sandell’s supporters (“Angie”) attempts to put this into context in the comments section of Burgas’ review:

“Sure, I agree that celebrity worship is shallow, but it’s here that you so obviously missed the point. Sandell herself draws the parallel between her larger than life father and her predilection toward celebrities. It makes perfect sense that someone whose entire childhood is based on appearance rather than substance would struggle mightily with the concept of self-worth. Sandell’s childhood was filled with one message: you’re nothing without something. Now, with that type of upbringing, how in the world would you expect for her to know the right thing to do as an adult?…Why am I so vehemently defending this book against your review? Because I was raised by a narcissist and I know the agony of trying to separate out people who are good for you and people who are not. I have spent nearly my entire adult life having to learn the very basic rules you clearly learned as a child. Not all of us are so lucky. It takes one mistake after another to gain insight. Sandell seems to make these mistakes, but you seem a bit lost to the insight.”

Sandell’s apologist would appear to be suggesting that the author’s celebrity worship is simply the product of an imbalanced mind but she goes a bit too far in claiming some form of epiphany on the part of the author. If anything there is at most a negotiated balance by the end of the book. There is every reason to believe that there are a number of people who find such a devotion to and respect for celebrity perfectly healthy and fruitful. If anything, Sandell’s book is one written in sympathy with this point of view as well as other similarly traumatized individuals.

There is certainly a degree of vanity on display throughout the length of Sandell’s book – in particular, the chosen ending and the author’s self-serving justification for her comic’s existence:

These traits are, however, far from exclusive to Sandell’s memoir and hardly a prescription for bad art.

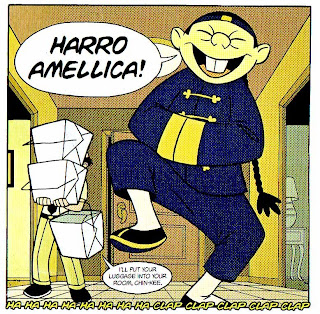

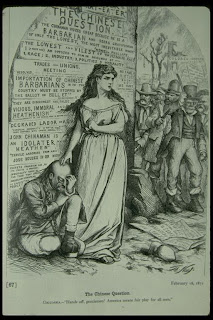

While Sandell’s book presents itself as therapy, there is no suggestion on the part of the author that she has achieved a complete “cure”. Whether by intent or accident, the author has laid herself bare for all the sticks and stones such public self-analysis and exhibitionism entails. Far worse deeds have been done in the pages of autobiographical comics – the comics of Joe Matt being a case in point:

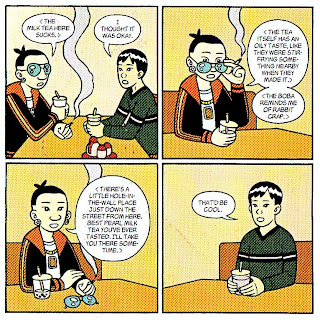

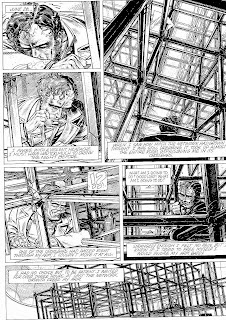

Joe Matt’s Peepshow provides an interesting comparison if only because no reader would imagine the author to be anything but an unpleasant character to befriend. Both Matt and Sandell derive a considerable amount of mileage from a degree of sensationalism – if anything, Matt is much bolder in his drive for “untouchability”. While some of Matt’s earliest multi-paneled autobiographical works delve into some degree of comics formalism, his later works are presented as straight narratives just as Sandell’s is. The real difference between the early works of Matt and Sandell’s comic lies in Matt’s firm grasp of cartooning, panel composition, comic timing and narrative pacing.

Sandell’s story by contrast is flatly narrated in a monotonous voice. Her narrative is both drawn out and tedious in its reiterations of the same subject matter. There is a distinct lack of creative structure and The Impostor’s Daughter reads like a book which was thrown together with little planning and forethought. If Sandell’s work has drawn more notice from the mainstream press, it is simply because of the stories’ greater accessibility and more “worthy” subject matter (as well as her publisher’s marketing abilities).

As for Sandell’s cartooning abilities, the less said the better. Her lettering skills are non-existent…

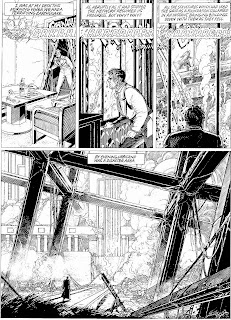

…and the range of emotions at her disposal limited. Her inability to convincingly depict anger or forcefulness is a crippling blow to the effectiveness of her narrative [dialogue removed for comparison].

Is Sandell’s mother having a blow out in the middle of a restaurant or excitedly telling her daughter about the latest collection from Manolo Blahnik? These are drawings that would make a grade school teacher cry in shame.

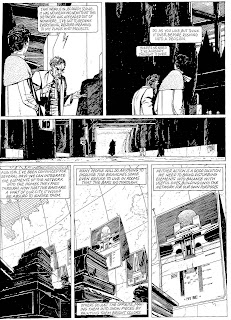

The next few images are from one of the most effective sequences in the book – a confrontation between the author and her father following her extensive investigations into his past. Consider Sandell’s rather basic grasp of cartooning which I’ll highlight once again by removing the dialogue:

Little of the effect of this scene is derived from Sandell’s drawings. The draftsmanship here is shoddy and Sandell’s grasp of body language limited. Her mother’s hasty disappearance is hardly more than a footnote done in barely discernible (and clumsy) shorthand. The drawings are in short merely functional – providing some immediacy to the encounter with the facial expressions giving some inkling as to the tone of the dialogue. The panel compositions, page layouts, lettering and coloring (done by Paige Pooler) give off little sense of darkness or danger. This scene, while critical in the development of the protagonist, is delivered as blandly as any other in the book.

One of the reasons why Sandell decided to create a comic about her childhood trauma is given in a publicity blurb in The Wall Street Journal:

“The idea hit her when she discovered a box of her childhood drawings in her parents’ attic. There were some 300 cartoons, mostly about her father, that she’d drawn between the ages of 7 and 10. “I saw that the entire story was there,” said Ms. Sandell, 38 years old, a contributing editor at Glamour magazine. “I’ve always been able to tell the truth about my father in cartoons.”

The decision to draw her story instead of simply writing it would appear to have been based primarily on the therapeutic possibilities of this choice. Yet the negative influence of Sandell’s drawing goes well beyond that of an aesthetic irritant. It significantly detracts from whatever message she hopes to communicate, removing the reader from any sense of reality or empathy with her situation. It is a sad comment on the effect of the book that I found more humanity in Sandell’s blog and level-headed response to Greg Burgas’ criticism than anything in her comic. Sandell becomes a “real” person in her blog (her spot illustrations adding charm to her writing), she’s a poorly drawn caricature in her comic.

While a master cartoonist like Lynda Barry may suggest (in books like What It Is) that anyone can create a story or comic, it is all too clear that a great comic is the product of years of honing one’s skill. Barry’s thinly disguised and deeply felt autobiographical comics demonstrate a beautiful sense of design and page composition. She has an exquisite ear for dialogue and a gift for clear emotive writing. Carol Tyler’s “The Hannah Story” is yet another example of such skills directed at a concentrated and elegantly structured tragedy.

Scott McCloud, a comics evangelist by nature, is far kinder about the effect of these drawings:

“Meanwhile, Sandell’s graphic novel is a mainstream book in nearly every sense. The (presumably) true story is told as literally as possible. Sandell is no virtuoso artist, but her layouts are sensible and the drawings get the job done. Cars look like cars, bottles look like bottles, and hands have five fingers. Every line and color choice serve the story, and the story is an engaging one, filled with mystery, sex, addiction, and the parade of celebrities Sandell encountered as a reporter and contributing editor at Glamour. It’s a beach read…I can imagine each of these books rubbing someone the wrong way. In some respects, Sandell’s glamour-sprinkled tell-all is a hard-core comics lover’s worst nightmare; a book deal fueled by celebrity, completely bypassing comics history and craft, ready to leapfrog more serious or well-crafted graphic novels onto The Today Show or even Oprah…I like Sandell’s book though, because it was a fun read. It can gently coax new readers into comics who would have never cracked open an Asterios Polyp much less a Blankets, and because a healthy mainstream has never precluded a healthy alternative.”

McCloud view is valuable because it explains why a distinctly amateurish work was given the full color hardcover treatment where more worthy work has often been allowed to fester neglected in the shadows. In all probability, what appears undemanding and insipid to me may in fact provide an entry point for a person new to comics. I am also disposed to believe that this was an attempt by Little Brown and Company to tap into the audience for graphic memoirs demonstrated by the success of works by Marjane Satrapi and Alison Bechdel.

Of course, one could easily posit the idea that a work like Sandell’s may confirm the prejudices of a reader not enamored of comics thus driving said person away from the medium forever. This problem is made more acute by the host of positive critical notices suggesting that this is a work of the highest order and not the comics equivalent of a “beach” novel as suggested by McCloud. There are certain standards which can be applied across all playing fields and Sandell’s comic clearly comes up short when these are applied.