Yesterday, Chris Gavaler wrote about female superheroes, arguing that they’ve been around for a while, that people of all genders love them, and that it’s about time we got to see a film dedicated to watching female superheroes hit things. Chris cited a study by Kaysee Baker and Arthur Raney that showed that, in superhero cartoons, women and men behaved just about the same — they hit things, they saved people, and so forth. Baker and Raney found this a little disturbing; they were worried that heroes of either gender had to be more masculine and aggressive to be heroic. To which Chris responds, well, who says that aggression has to be masculine? “Because if aggression is now gender-neutral, how can being aggressive also be “more masculine”?”

Chris has a point — and that point is a neat summation of empowerment feminism, which is the feminist perspective which says that women should be able to do everything men do, especially if that “everything men do” includes holding and wielding power. The lean in movement is empowerment feminism, and so (as Chris shows) is the enthusiasm for female superhero movies and the desire to see Hawkgirl bash in some baddie with her mace. America is really into power (we’re a superpower, after all) and so it’s not a surprise that empowerment feminism is generally speaking the most popular manifestation of feminism.

It’s so popular, in fact, that it can be easy to forget that it doesn’t necessarily appeal to everyone all the time. But here, at least, is one dissenting voice.

[Wonder Woman’s] creator had…seen straight into my heart and understood the secret fears of violence hidden there. No longer did I have to pretend to like the “Pow!” and “Crunch!” style of Captain Marvel or the Green Hornet. No longer did I have nightmares after reading ghoulish comics filled with torture and mayhem, comics made all the more horrifying by their real-life setting in World War II…. Here was a heroic person who might conquer with force, but only a force that was tempered by love and justice.

That’s Gloria Steinem, describing her relief at discovering the original Marston/Peter Wonder Woman comics, in which, as she intimates, there weren’t a ton of fisticuffs and violence. Instead, Wonder Woman tied the bad guys up with her rope of love — and was tied up by them. Loving submission and bondage games, yes; bashing people’s heads in with maces, not so much.

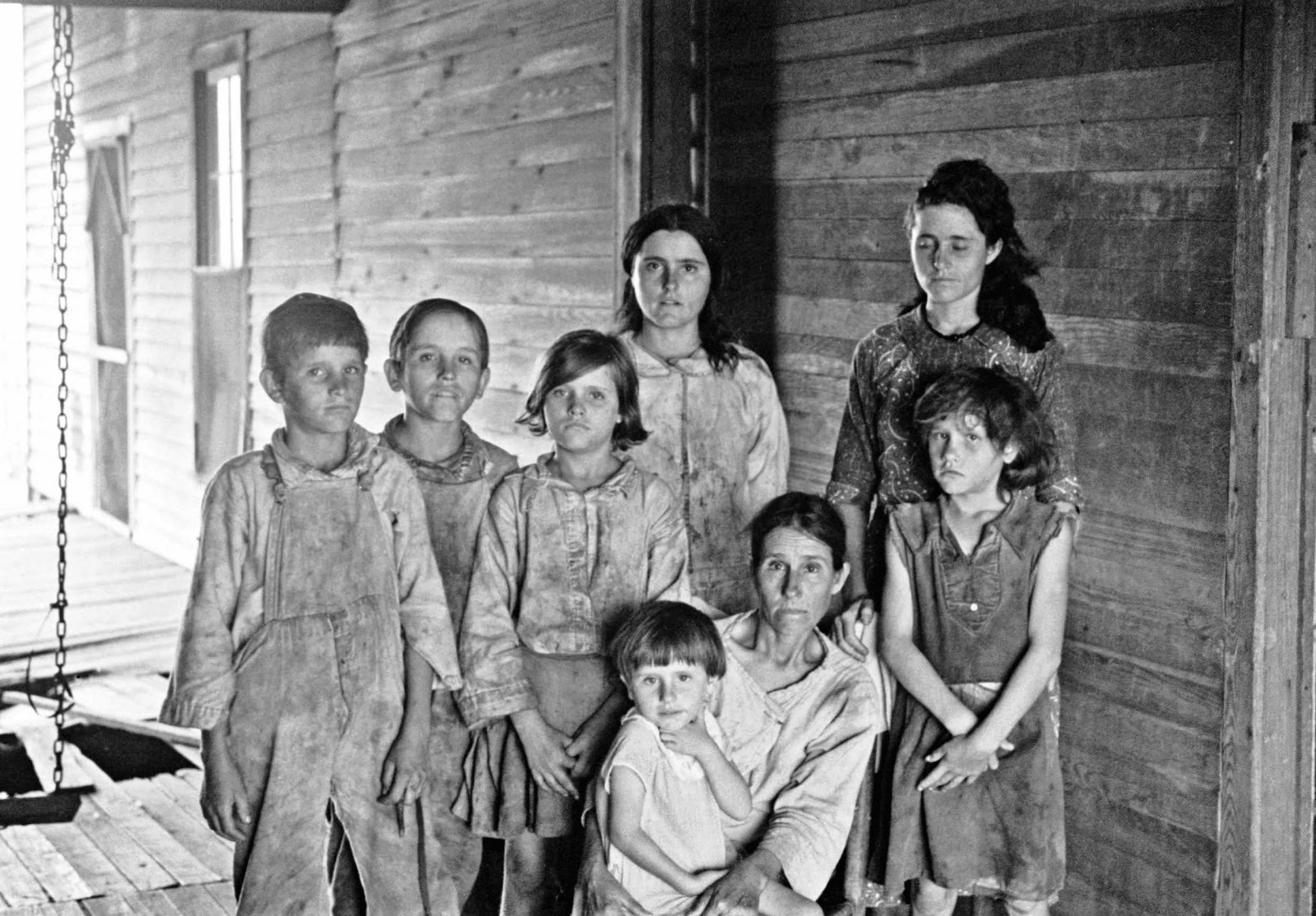

Chris rightly points out that there isn’t anything essentially masculine about violence; there are plenty of women throughout history who have enjoyed hurting other folks. And yet, at the same time, you don’t just get out from under millenia of culture by having Scarlet Johansson kick somebody. Violence and aggression and war have traditionally been encoded male. Lots of feminists, from Steinem to Virginia Woolf to William Marston, have pointed out that masculinity is wrapped up in an ethos of force and violence — that being a man means, in many respects, being violent. And while one reaction to that can be, with empowerment feminism, to point out that women can be violent too, another approach is to say that the non-violence which has traditionally been associated with women is not an aberration or a failing, but a resource. Women do not have to be embarrassed or ashamed that they don’t like Captain Marvel hitting people; rather, they can point out that hitting people is possibly not such a great way to solve problems, and that equating goodness manliness and heroism with hitting people is, perhaps, a failure of imagination which can, under the right circumstances, get people needlessly killed.

Along those lines, one of the things that I most enjoy about the new Ms. Marvel series by G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona is how uninterested it is in uber-violence. Three issues in, and our teen protagonist, Kamala Khan, has encountered exactly zero supervillains. After she gains her shape-shifting powers, the first thing she does is to turn her hand giant (embiggen!) and fish a damsel in distress out of a lake. The damsell in question fell in the lake after her boyfriend knocked her in — not in the process of a sexual assault, as you’d think if you’d read too many superhero comics, but simply out of stupidity and drunken horsing around. This is a world in which heroes exist and heroism matters, but it’s not a world in which that heroism is necessarily linked to violence.

In issue #3, Kamala does have her first fight. She sees her friend/sweetie-in-waiting Bruno getting held up at the convenience store where she works, and (after trying to call for help and discovering her cell phone is out of batteries) she transforms into Ms. Marvel and starts swinging with her giant embiggened fist.

Sort of. The robber is Bruno’s brother, and he’d already given up on the theft before Kamala barged in. She easily defeats him, crushing him in with that fist (“you’re squeezing really hard!”)…but not before she does far more property damage than he ever could have managed by himself. And then, after she lets him go (he’s promised to apologize and never come back) he accidentally shoots her. The last image of the comic is of Ms. Marvel sitting on the ground, her giant hand extended out in front of her, looking shocked and confused, an iconic hero reduced to a confused adolescent girl, as the guy she was saving freaks out and the “villain” sits off to the side looking at the gun in his hand in horror.

My suspicion is that Ms. Marvel is going to discover that her rubbery hide is effectively bullet proof, and hopefully all will end more or less well. But it’s rather nice to have a superhero story where violence ends up being, not a solution, but a complication.

Ms. Marvel, in other words, critiques super-hero violence — and the reason it’s able to do that is absolutely in part because the series is not just a superhero story, but a girl YA coming of age story. The narrative is interested in Kamala having adventures, definitely, but it’s also interested in her figuring out who she is, which means (among other things) working out her relationship with her (shape shifting, sometimes adult Caucasian va-va-voom superhero, sometimes adolescent Muslim girl) body and discovering that her annoying good geeky friend is in love with her. Lee and Ditko couldn’t figure out how to make Spider-Man a man except through violence and trauma and more violence. G. Willow Wilson, though, is drawing on a narrative tradition quite different from boys’ adventure, which means that for her, growing up doesn’t need to mean watching your dad die and beating up his killer.

Ms. Marvel has been exceedingly popular (it keeps selling out at my local comics store) — but, given the low sales of even really popular comics, it seems unlikely that it will be turned into a superhero movie any time soon. Still,it’s worth noting, perhaps, that other superhero stories about women on the big screen — the Hunger Games, say, or Twilight (where Bella gets to be a superhero by the end) are significantly more ambivalent about violence, its effects, and its efficacy than the standard Marvel/DC superhero/supervillain thump-fests tend to be. Maybe that’s because they’re working to appeal to women (and for that matter men) like Gloria Steinem, for whom narratives of violence are alienating rather than empowering.