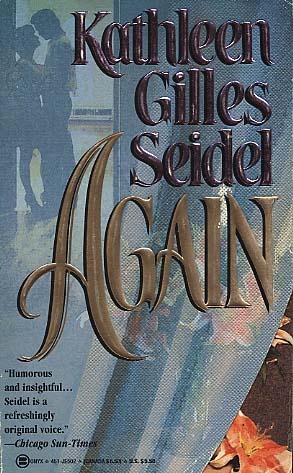

Many romances are meta, but surely few can be as meta on their meta as Kathleen Gilles Seidel’s iteratively titled Again. The novel’s heroine, Jenny Cotton, is the chief writer on a soap opera, My Lady’s Chamber, which is set in the Regency period. The novel, then, is both a historical and a contemporary, with the two constantly commenting on each other, as Jenny distributes the characteristics of her unsatisfying maybe-soon ex Brian and her possibly potential suitor Alec to various period figments of her imagination. Jenny has been with Brian since they both were children, but she only discovers that he’s a selfish git incapable of generosity or caring when Alec, playing the evil duke Lydgate (where’d that name come from?) picks up on one of Brian’s characteristic mannerisms. So Jenny reads Brian by reading Alec, or more accurately, Jenny reads Jenny by reading Alec reading Jenny reading Brian — which is to say, Jenny figures out that she has modeled Lydgate on Brian when Alec playing Lydgate picks up on Brian’s mannerisms to portray the character. Past, present, self and other, and, most emphatically, reader and read are shuffled about as in a shell game; the heart (whose heart? everyone’s heart?) is revealed simultaneously through reading and being read — the protagonist as text, reader, and critic.

Many romances are meta, but surely few can be as meta on their meta as Kathleen Gilles Seidel’s iteratively titled Again. The novel’s heroine, Jenny Cotton, is the chief writer on a soap opera, My Lady’s Chamber, which is set in the Regency period. The novel, then, is both a historical and a contemporary, with the two constantly commenting on each other, as Jenny distributes the characteristics of her unsatisfying maybe-soon ex Brian and her possibly potential suitor Alec to various period figments of her imagination. Jenny has been with Brian since they both were children, but she only discovers that he’s a selfish git incapable of generosity or caring when Alec, playing the evil duke Lydgate (where’d that name come from?) picks up on one of Brian’s characteristic mannerisms. So Jenny reads Brian by reading Alec, or more accurately, Jenny reads Jenny by reading Alec reading Jenny reading Brian — which is to say, Jenny figures out that she has modeled Lydgate on Brian when Alec playing Lydgate picks up on Brian’s mannerisms to portray the character. Past, present, self and other, and, most emphatically, reader and read are shuffled about as in a shell game; the heart (whose heart? everyone’s heart?) is revealed simultaneously through reading and being read — the protagonist as text, reader, and critic.

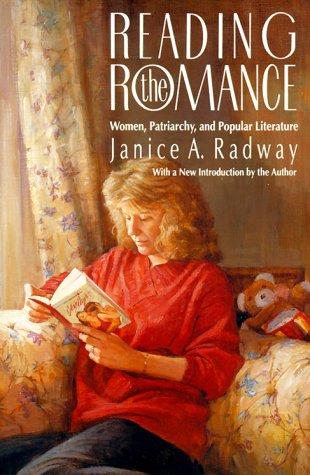

Not just any critic, either. Like Jennifer Crusie’s Welcome to Temptation, Seidel seems to deliberately reference and engage with the major early feminist critic of romance, Janice Radway (and probably also with Tania Modleski, whose work drew explicit parallels between romance and soap opera.) Radway argued, following Nancy Chodorow, that the romance genre was a fantasy of reconcilement with the mother. Romances, she said, presented brutal men who were eventually melted by love into unexpectedly maternal softies, providing women with the consolatory dream of a caring patriarchy of love and empowerment, and so enabling them to tolerate their inadequate marriages and lives.

Radway’s thesis is quite unpopular with many current romance readers, if my experience mentioning her name on social media is any guide, and Seidel is undoubtedly being arch when she provides an almost parodically perfect Radway narrative of man-as-mother-substitute. Jenny’s own mother died when she was a year old, and as a result she feels that she never learned how to be a woman, and never had anyone to take care of her. For his part, Alec is an obsessive care-taker; in just about his first meeting with Jenny, he discovers she’s having a miscarriage and bustles her off to the hospital, literally sweeping her off her feet to carry her at one point. She needs a mother; he’s a mother. The Radway formula, illustrated.

Except it doesn’t quite work that way. While Jenny wants a mother, she rather hates being taken care of. For his part, Alec over the course of the novel runs through his emotional reserves; he falls in love with Jenny, but the strain of constantly trying to take care of everyone (as he once took care of his terminally ill sister) eventually renders him inert. The storyline resolves not through Jenny discovering a mother in Alec, but rather through her realization that she, herself is her mother. She always thought that her mother would have been good at the “girly stuff” — dressing up, being frilly and elegant and glamorous. But after breaking up with Brian the jerk, Jenny realizes that her mother (whose chief love was driving around from pool hall to pool hall with Jenny’s pool shark dad) was just as much of a tomboy as her daughter. Jenny doesn’t need a guy to be a mother because she was always already her mother herself. Instead, it’s the mothering guy who needs to be taken care of. Or as Alec puts it (after some coaching from Jenny, feeding him his lines as is her wont) “I need you to explain to me how I need you.”

Except it doesn’t quite work that way. While Jenny wants a mother, she rather hates being taken care of. For his part, Alec over the course of the novel runs through his emotional reserves; he falls in love with Jenny, but the strain of constantly trying to take care of everyone (as he once took care of his terminally ill sister) eventually renders him inert. The storyline resolves not through Jenny discovering a mother in Alec, but rather through her realization that she, herself is her mother. She always thought that her mother would have been good at the “girly stuff” — dressing up, being frilly and elegant and glamorous. But after breaking up with Brian the jerk, Jenny realizes that her mother (whose chief love was driving around from pool hall to pool hall with Jenny’s pool shark dad) was just as much of a tomboy as her daughter. Jenny doesn’t need a guy to be a mother because she was always already her mother herself. Instead, it’s the mothering guy who needs to be taken care of. Or as Alec puts it (after some coaching from Jenny, feeding him his lines as is her wont) “I need you to explain to me how I need you.”

In Radway’s formulation, romance is a trans-gendered pleasure — a fantasy of women loving the women within men. Seidel’s reworking doesn’t so much put every gender back in its place as it infinitely iterates (“Again”) the cross-gender swapping. Jenny, the tomboy, becomes the caring man as mother; Alec, caring man as mother, becomes the woman swept away and cared for. “Someone else was making everything absolutely perfect,” he thinks at the end. “There was something to be said for a woman with imagination.” The “woman” there is supposed to refer to Jenny — but given the fact that imagination for Radway is figured specifically as the transgendering of the love object, it must also refer to Alec, who, transgendered himself, is the one experiencing the characteristically Radwayian romance of motherly protection from a strong patriarchal figure (she is, after all, his boss.)

This scrambling of gendered positions is in part a critique of Radway’s critique of romance. Romance, Seidel says, is not (or doesn’t have to be) about fooling oneself into thinking that the patriarchy is your mother; it can be about insisting that women can take care of themselves, both personally and professionally. But if that’s critique, it also seems like conversation — and, perhaps, assurance. Psychoanalysis is always, after all (as that prime fetishist Freud demonstrates) self-psychoanalysis, which means that Radway’s supposed excavation of the romance readers psyche might perhaps better be read as a projection of Radway’s own particular neuroses.

And that is in fact how Seidel reads it. In a footnote to her discussion of Radway in the collection Dangerous Men & Adventurous Women, from 1992 (just two years before Again) Seidel says this:

Janice Radway, in her 1987 introduction to the British edition of Reading the Romance…acknowledges the “residual elitism which assumes that feminist intellectuals alone know what is best for all women.” In a graceful, moving statement, she suggests that such scholars should offer romance readers and writers “our support rather than our criticism or direction.” She follows this generous-hearted position with the most discouraging words I encountered in all the reading I did for this essay as she dismisses the possibility: “Our segregation by class, occupation, and race [race?] works against us.” We are still Other to her; she does not believe either party can speak to the other. I find this inexpressibly sad.

Seidel, then, reads in Radway a tragic fissure, a split between women and women — which is precisely the tragic fissure that Radway reads into romance readers and writers like Seidel. It is not romance readers, but Radway, who is bifurcated; it is not romance readers, but Radway who needs to be reconciled with the mother — or, in Seidel’s version, to realize that she is already reconciled with the mother, and that the romance is already hers.

Again, then, can be read, not as (or not just as) a refutation of Radway, but as a love letter to her. And part of what that love letter says is that Radways’ book is itself a love letter — that “Reading the Romance” can itself be read as a romance.

That romance isn’t utterly untroubled. Seidel has a lot of fun in the novel with a rival soap opera, Aspen!! written by the (significantly) male writer Paul Tomlin, a man who “didn’t know anything about soaps”, and who seems to have contempt for the form and for the audience. The satire of those who hope to save romance and romance readers for better, higher things certainly implicate Radway, tweaking her condescension and her separation of herself from her subject — the way she wants to write in romance without actually writing romance.

But the very act of criticizing the critic puts one, inevitably, in the position of critic. The original name of Aspen!! was Aspen Starring Alec Cameron; the Othering Othered is also the loved one — albeit a loved one who needs to be taught to love. And that teaching is criticism, too. “I suppose we’re to conclude from that that my best chance of being an acceptable human being is to be married to you?” Alec says, after Jenny has explained their relationship to him through a critical reading of the ongoing plot of In My Lady’s Chamber. Criticism speaks romance and romance speaks criticism. And when the genres are so nested in each other, how can you tell who is outside or who is inside, or who is saving whom?