This first appeared on Comixology.

______

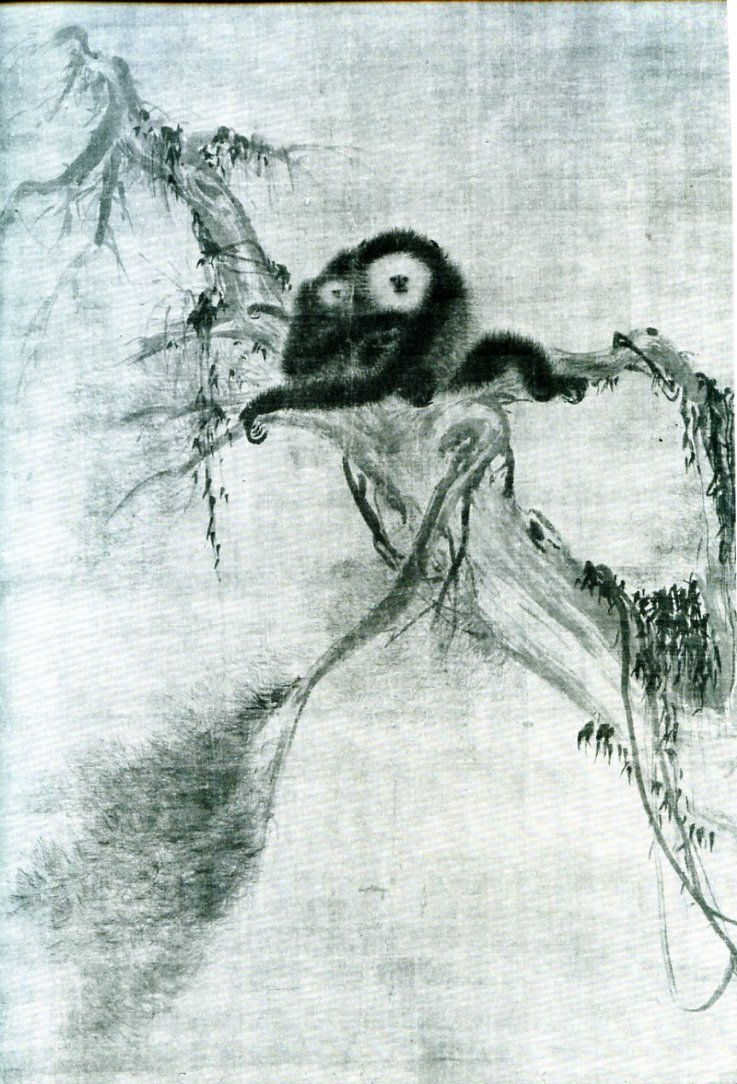

The triptych above was supposedly painted by Mu-ch’i, a Chinese monk, in the 1200s. The middle picture is of Kuan-yin, a much-revered bodhisattva, who had decided to remain on earth and help others to attain enlightenment rather than preceding on to a higher plane. The other pictures, obviously, are of a monkey and a crane.

In the book, Zen Ink Paintings, Sylvan Barnet and William Burto suggest several possible reasons for the juxtaposition of bodhisattva and random fauna. On the one hand, they say, the crane may symbolize intellect, while the monkey (with its child) may symbolize love, the suggestion being that Kuan-yin is a fusion of the two — as, indeed the bodhisattva is generally seen as a fusion of both male and female. Or, alternately, the authors say, the placement of the animals beside the bodhisattva may be a way to connect the human, the divine, and the animal in a single harmony. Or, possibly, the crane may be meant to stand for extended life, thereby making fun of the Taoist desire for immortality, while the monkey stands for family, satirizing the Confucian emphasis on household harmony.

My favorite interpretation, though, is based on these lines from a contemporary poem which Barnet and Burto quote:

An old monk arrayed in purple

Would be laughed at by monkeys and cranes.

From this perspective, the crane and the monkey are there, not to make fun of Taoism or Confucianism, but to make fun of Kuan-yin. Certainly, the crane, with its mouth open, can be seen to be laughing at the serenely oblivious bodhisattva. Moreover, the crane’s oval shape seems to mirror the bundled shape of Kuan-yin’s robes; it’s as if the artist is deliberately mimicking the central figure, turning Kuan-yin from a divine ideal into just a goofy waterbird. Something similar seems to be going on with the monkey too; curled up and staring out of the canvas, she mirrors and parodies the bodhisattva’s solemnity. The one monkey leg reaching out across the branch imitates Kuan-yin’s trailing robes; the long arm reaching crossways across the body seems like a mockery of Kuan-yin’s own crossed arms. On the one hand, the bodhisattva is parodied for being like an animal; on the other, both side-pictures seem to be poking fun at him for his reserve and determined spirituality. The crane’s neck curves as if ready any moment to jerk with a squawk; the monkey’s soft fur almost quivers in the wind — and the bodhisattva just sits there.

If the crane and the monkey are teasing Kuan-yin, perhaps they’re also teasing someone else — specifically, you. The monkey, after all, isn’t staring at Kuan-yin, but out of the picture; its position may mirror the bodhisattva’s, but it also in some sense looks like a mirror. The crane, too, could be a passing onlooker, staring at the bodhisattva’s picture with his or her mouth agape. Kuan-yin’s calm here may be in contrast to these unenlightened viewers, who squat like monkeys or strut like cranes, curious but oblivious. Or, perhaps, the joke isn’t that the audience is unworthy of enlightenment; but rather that they are already enlightened. Because they are as undignified as the monkey or the crane, those who contemplate the picture have their own plain, contingent place within it, like cranes or monkeys who happen to be nearby when the bodhisattva comes.

In an essay titled “Humour and Faith,” Reinhold Niebuhr said,

The intimate relation between humour and faith is derived from the fact that both deal with the inconguities of our existence…. When man surveys the world, he seems to be the very center of it, and his mind appears to the be the unifying power which makes sense out of the whole. But this same man, reduced to the limits of his animal existence, is a little animalcule, preserving a precarious moment of existence within the vastness of space and time.

The joke here, then, is on man, the little animacule, who can reflect on himself like Kuan-yin, and who sees in that reflection a monkey. For Niebuhr, as a Christian, this absence of meaning is finally resolved, at its limits, not by laughter, but by faith. As he says, “We laugh cheerfully at the incongruities on the surface of life, but if we have no other resource but humour to deal with those which reach below the surface, our laughter becomes an expression of our sense of the meaninglessness of life.”

You could see this as the point of this triptych as well, which starts on its outer edges with laughter and moves, at its center to a divinity which binds both animal nature and human watchers together in contemplation of the divine.

The caveat is that the “meaninglessness of life” doesn’t mean quite the same thing for the Protestant Niebuhr as it did for the Buddhist artist. Niebuhr can see laughter as directed at human beings, but when he thinks about laughter directed at divinity, he ends up talking about Jesus’ tormentors mocking Christ on the cross. In this vision of Buddhism, though, laughing at creation doesn’t have the same connotations of blasphemy.

In this context, the best part of the joke here, and maybe the most Buddhist part as well, is that all of these speculations about the triptych— mine and Barnet and Burto’s — are quite likely, and precisely, nonsense. Nobody really knows if the crane and the monkey and Kuan-yin form a triptych. The three may well have been assembled haphazardly long after the artist’s death. The only meaning in the juxtaposition of images is the meaning you graft onto it yourself; the pictures make a story because you say they do. There’s no more sense there than the silent croak when the crane opens its mouth, or than Kuan-yin sitting as poised as a monkey on a branch. The crane laughs at you because it knows it isn’t laughing at you, and the monkey mocks you because it knows it isn’t. Flanked by them both, Kuan-yin seems content to be ridiculed both by the animals’ presence and by their absence. Enlightenment’s a joke that isn’t, then is, then isn’t.