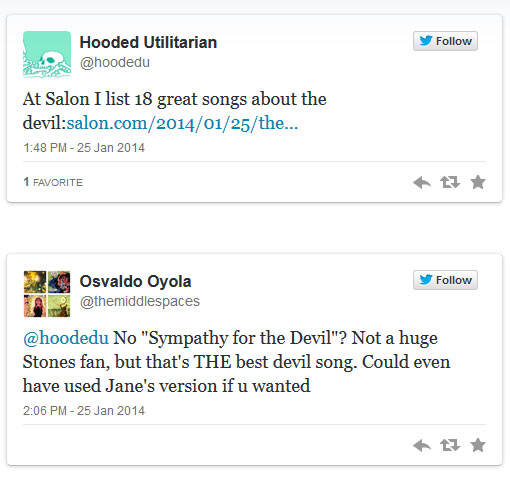

A very slightly different version of this post first appeared at The Middle Spaces.

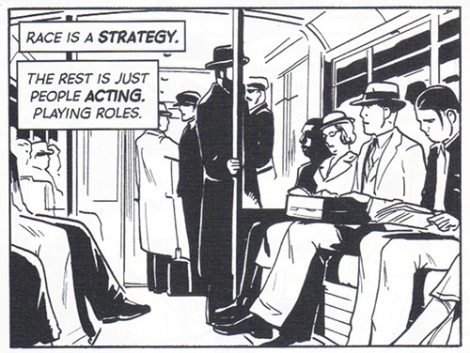

At the end of last year, Orion Martin wrote a piece for The Hooded Utilitarian entitled, “What If the X-Men Were Black?” that argues that the metaphor of Civil Rights issues as persecuted mutants fails, or that at the very least the elasticity of the mutant metaphor to cover race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity means that it’s susceptible to appropriation and undermines any ability to productively comment on those social issues. Impressed by this essay, I thought it would be interesting to look again at the first arc of Brian Wood’s recent X-Men series, which features a much hyped team of all women and see what the result might be of a mutant superhero group in which the persecution metaphor might be peeled away due to the fact that all the team members are women, in favor of a more direct reflection on issues facing women, both as members of the X-team, but also as characters who ostensibly directly represent a real-world (albeit diverse and far from monolithic) political identity.

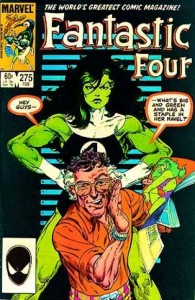

Marvel’s X-Men has a decent history of including women in its super-teams, sometimes even in the role of leader. You have to ignore the original X-Men where Marvel Girl (aka Jean Grey) was the only woman, but later, Jean would be joined by Storm, and then Kitty Pryde, Rogue, Rachel Summers, Psylocke, Dazzler, Jubilee, and so on… The New Mutants had Wolfsbane, Karma, Dani Moonstar, Magma. Various forms of X-Factor and X-Force all had women team members. In fact, take Dazzler and Jean Grey out of that first list and you have the core of Wood’s X-Women team, but that record of including women is still only good in relation to the rest of superhero comics. There are still a ton of more men in the X-Men than women, and aside from Storm and Jubilee, the most popular X-Women have all been white…

Marvel’s X-Men has a decent history of including women in its super-teams, sometimes even in the role of leader. You have to ignore the original X-Men where Marvel Girl (aka Jean Grey) was the only woman, but later, Jean would be joined by Storm, and then Kitty Pryde, Rogue, Rachel Summers, Psylocke, Dazzler, Jubilee, and so on… The New Mutants had Wolfsbane, Karma, Dani Moonstar, Magma. Various forms of X-Factor and X-Force all had women team members. In fact, take Dazzler and Jean Grey out of that first list and you have the core of Wood’s X-Women team, but that record of including women is still only good in relation to the rest of superhero comics. There are still a ton of more men in the X-Men than women, and aside from Storm and Jubilee, the most popular X-Women have all been white…

Racial Aside #1: Psylocke complicates the “white women” aspect of this analysis, but in a way that highlights the deep problems with representations of race and ethnicity in superhero comics. I never gotten over her 1989 transformation from Captain Britain’s big-haired hippie sister into hottie Asian ninja in butt-floss. My complaint about Psylocke is not the race-bending—I am all in favor of black Human Torch or Heimdall and support people’s desire to see an Asian-American Iron Fist—but that her transformation was written into the X-narrative to fulfill the dual fetish of the Asian woman and the exotic ninja killer trope is egregious. She just looks “Asian.” (Well, kind of. There was also some kind of genetic manipulation of the body afterwards or something. Who can keep this stuff straight?) She is literally an Anglo woman whose mind has been put in an Asian woman’s body with no connection to any form of Asian culture or family or community, except in the most facile way that being a “ninja” makes that the case.

Racial Aside #2: Bling! (yes, the exclamation point is part of her name) is a queer African-American student and X-Man in training at the school during this series. However, her crystalline appearance obscures any physical racial markers, and more troubling, her codename and backstory (she is the daughter of a famous rapper couple) become the primary way race is encoded on her.

Racial Aside #2: Bling! (yes, the exclamation point is part of her name) is a queer African-American student and X-Man in training at the school during this series. However, her crystalline appearance obscures any physical racial markers, and more troubling, her codename and backstory (she is the daughter of a famous rapper couple) become the primary way race is encoded on her.

So with that history of better than average—but not good enough—representation of women in X-Men comics and of the team itself being used as a metaphor for disenfranchised groups, it seems fair to judge this X-Women comic with that in mind, and as such, I can say with some confidence, that it fails. Furthermore, if a focus on a new team of women characters was to any degree supposed to attract new readers—more women and/or folks intimidated by the steep learning curve of 50 years of continuity who might see this as a fresh start—it totally fails on that account as well.

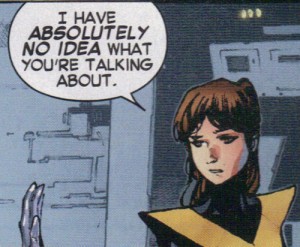

I first picked up these issues of Wood’s X-Men not only because I was interested in the representation of women in this comic, but mostly because Rogue, Kitty, Storm and Rachel are sentimental favorites of mine. The height of my collecting X-Men was in the 1980s, and if you don’t count the handful of issues of Grant Morrison’s early New X-Men run (in 2001) that I quickly got rid of, I bought no X-Men comics between 1988 and 2004 when Whedon and Cassaday’s Astonishing X-Men series came out (a series that managed to capture something akin to my memory of the X-Men’s voices from the 1980s—as opposed to the Claremont-reality, which in returning to those early issues I found to not be as good as I remembered), and those 80s comics shaped what I consider my ideal and “most authentic X-Men.” I don’t know from Gambit or Bishop or Jubilee or whoever. That said, despite my fragmentary knowledge regarding 1990s X-Men, I do not count myself as a total neophyte regarding the comics’ characters and major tropes. I’ve managed to glean some info from that era via friends and Wikipedia, and yet in reading this series I found myself struggling to follow what was going on, what was at stake, and why I should care. It’s not hard to imagine that someone totally new to the comics would have been even more lost.

I am not one to complain about the frequent re-booting of numbers in contemporary superhero comics. Personally, I’d prefer for all on-going titles to be series of varying lengths—volumes bound together by time period and or theme, and creative team. I think this would help overcome the crippling burden of continuity, make comic stories easier to organize, and most importantly provide frequent places for new readers to jump on. What is the point of starting a new series with a new number one, if the very first arc is so enmeshed in established continuity that the reader is struggling to catch up with stuff that happened years before in some other version of the series? This is especially the case when the guest star/villain is someone that is basically an obscure character that does not have connection to the iconic stories of X-Men past that might have some reach beyond the die-hard comic fans. Back in the height of my collecting days as a kid, Jim Shooter, Marvel’s editor-in-chief, enforced the philosophy that every comic was potentially someone’s first, and as such writers should write with that in mind. I am not suggesting that we need to go back to the days where a page or two of every issue is dedicated to re-cap, but I do think that, if all that “Marvel NOW!” bullshit is going to really mean anything, any new series needs to make an effort to introduce characters and situations. And I do think it is bullshit, because let’s face it, the urge to completism is what pushes modern comic marketing—own the whole series, own all the variant covers, get the collected trades if you miss something, so that you can understand what happens next. The reason folks complain about the rebooting of numbers, is not so much the numbers themselves, is because despite the editorial lipservice to creating places for new readers to jump on, the re-numbering is about manipulating the collecting culture’s penchant to obsessively pick up first issues despite the harsh lessons of the 1990s comic market collapse. The weak effort of these Marvel NOW! issues and series to actually introduce characters and create something of a fresh start (at least narratively) just reinforces that Marvel is more interested in wringing out every last sale from current readers than finding new ones. It is a classic case of diminishing returns.

There is no effort in this “new” series to establish the characters, but even worse there is no effort to establish or explain why this particular iteration of X-Men…X-Women…exists. It seems like these characters just happen to be the ones who are around when Jubilee calls to say she needs help. If anything, the fact that Jubilee’s problem includes a baby she has recently adopted and is responsible for, suggests that her entre into maternity is what makes this a case for the women of the X-team.

Jubilee is being pursued by John Sublime… Who? Some villain from the X-Men’s past we are told is immensely powerful and dangerous, but if you don’t know who John Sublime is (and I had never heard of him), there is no sense of what he is really capable of, what he has done in the past, and what is at stake in potentially trusting him when he claims to have arrived not to hurt Jubilee, her baby or the X-Men, but to warn them of a new threat. I used Google to look up Sublime’s history and found his backstory to be nauseatingly convoluted and kind of stupid. Stupidity I can handle. These are superhero comics after all, but without any real introduction his presence loses any impact it might have to all save the most informed X-Men fan. I guess he is some kind of hyper-evolved sentient bacteria that can possess people and has psychic powers? Maybe? Actually, even after reading the comic I am not sure what his powers are, because even though he ends up allying with the X-Men, he is never depicted using them.

Jubilee is being pursued by John Sublime… Who? Some villain from the X-Men’s past we are told is immensely powerful and dangerous, but if you don’t know who John Sublime is (and I had never heard of him), there is no sense of what he is really capable of, what he has done in the past, and what is at stake in potentially trusting him when he claims to have arrived not to hurt Jubilee, her baby or the X-Men, but to warn them of a new threat. I used Google to look up Sublime’s history and found his backstory to be nauseatingly convoluted and kind of stupid. Stupidity I can handle. These are superhero comics after all, but without any real introduction his presence loses any impact it might have to all save the most informed X-Men fan. I guess he is some kind of hyper-evolved sentient bacteria that can possess people and has psychic powers? Maybe? Actually, even after reading the comic I am not sure what his powers are, because even though he ends up allying with the X-Men, he is never depicted using them.

The new threat to which Sublime has come to warn the X-Men is his sister, Arkea (I didn’t know bacteria had sibling relationships or identified as a particular genders—like I said stupid—but I am willing to overlook this), except she doesn’t possess people, she possesses machines. That is, except for Jubilee’s baby. She hitches a ride on him, but this is never explained. . I guess it is possible that this baby has a neuro-prosthetic device that allowed Arkea to possess him, since he comes from a hospital where we are told that work is done, but again, it is not explained. In fact, a simple three-issue arc can’t even keep the effects of the possession on the baby (Shogo) straight. Sublime tells Jubilee in issue #3 the reason the baby has been asleep the whole time is because of the possession, but we are shown the baby awake in a panel in issue #1 when he is ostensibly still possessed.

There are several things like this in the narrative—small details that seem to be explaining something, but that only lead to more questions. For example, I guess Rogue can’t fly anymore without absorbing someone else’s power to do so, but still has super-strength and invulnerability? I am sure some X-Men superfan would be able to explain it to me, and a reference to Northstar suggests he was the source of her flight and speed, but since Northstar doesn’t actually appear in the comic, it remains unclear. Again, I can imagine that an X-Men neophyte would really have no idea what that meant despite this being an introductory issue.

Arkea is mostly a direct threat through her possession of Karima Shapandar. Who? This is another character I had never heard of and whose history as an “Omega Sentinel” is deeply convoluted. So, we have a new foe who wants to take over the world who is connected to one former villain turned temporary ally, to another one-time villain turned ally who was in some kind of coma in Beast’s lab until possession by Arkea wakes her up. We are told that Karima the Omega Sentinel is also very dangerous, but since we are simply told all of this in a way that mostly relies on previous knowledge, there is little sense of what is at stake in this story-arc except the most generic idea of Arkea “dominating the world.” Oh, and I guess Karima is their friend, so the X-Men are reluctant to harm her body even though her brain is likely dead.

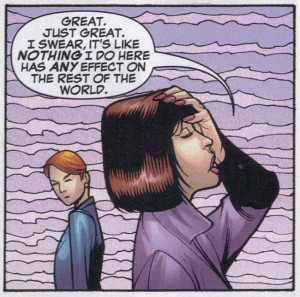

It is certainly possible that some, if not all of these omissions and poor plotting and characterization are addressed in later plot arcs in Wood’s X-series, but I wouldn’t know because I gave up after the first three issues. There was nothing that made me want to keep up with it, and I am confident that a new reader drawn to a point where in theory they could jump on would likely feel the same way. In fact, I would go as far to argue that this would be especially true of a reader drawn to the ostensible appeal of an all-women X-team, since there is never any effort to make this iteration of the team cohere except as the most cynical sales ploy that is only notable on the meta-level. And if it were to bomb, well then editorial would have an example of an all-women comic that failed to point to when explaining that they just don’t sell—rather than examining their own publishing practice and the flaws in the story-telling (See the recent Fearless Defenders series for another example).

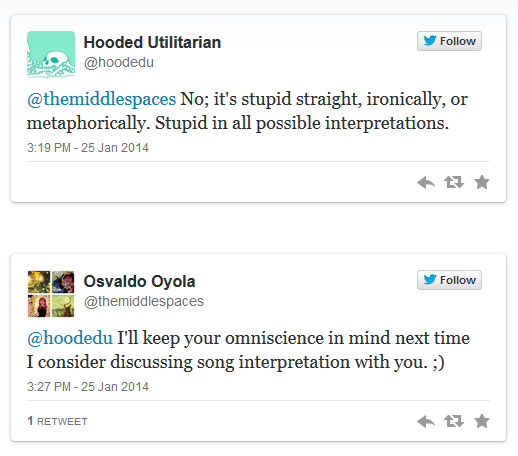

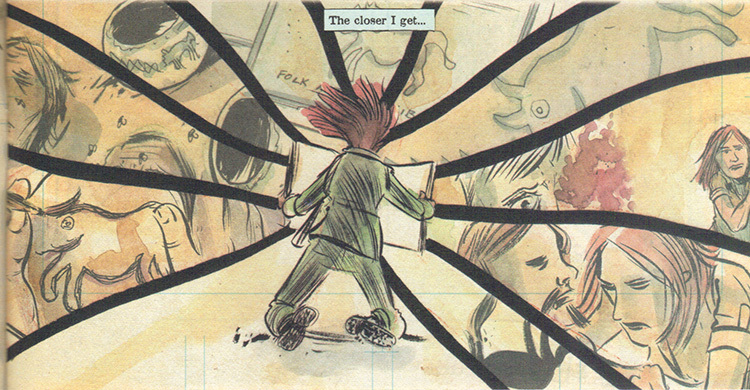

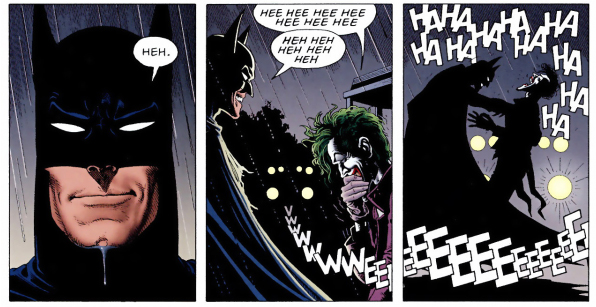

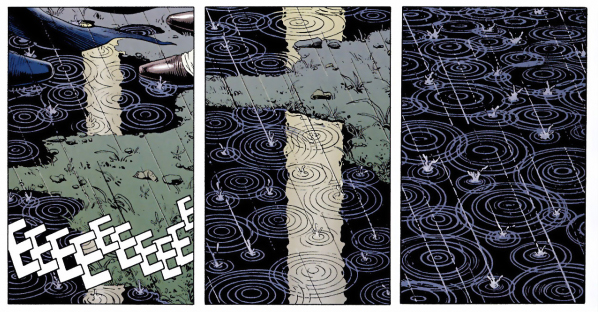

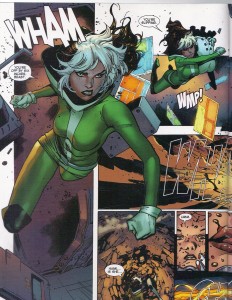

The only saving grace of these three issues is the art by Olivier Copiel and a team of inkers and colorists. In particular, I enjoy the depiction of a scene in issue #2, where Rogue smashes her way into Beast’s lab and seems to break through the panels to evoke her strength and sudden arrival. Generally, speaking the women in these issues are not drawn in the awkward positions meant to display all their physical assets at once, leading to ridiculous contortions, and even Psylocke is drawn with a different uniform from her purple butt-floss ninja classic. I like Rachel Summers Final Fantasy-inspired long red leather coat as well. But there is still some of the typical comics cheesecake, like Akrea/Karima’s semi-supine form when she first awakens or the way Psylocke seems to stick out her butt when she uses her psi-bow, or whatever it’s called. Some of the action sequences are also well-conveyed by the art, though, especially the train derailment sequence in the first issue.

The only saving grace of these three issues is the art by Olivier Copiel and a team of inkers and colorists. In particular, I enjoy the depiction of a scene in issue #2, where Rogue smashes her way into Beast’s lab and seems to break through the panels to evoke her strength and sudden arrival. Generally, speaking the women in these issues are not drawn in the awkward positions meant to display all their physical assets at once, leading to ridiculous contortions, and even Psylocke is drawn with a different uniform from her purple butt-floss ninja classic. I like Rachel Summers Final Fantasy-inspired long red leather coat as well. But there is still some of the typical comics cheesecake, like Akrea/Karima’s semi-supine form when she first awakens or the way Psylocke seems to stick out her butt when she uses her psi-bow, or whatever it’s called. Some of the action sequences are also well-conveyed by the art, though, especially the train derailment sequence in the first issue.

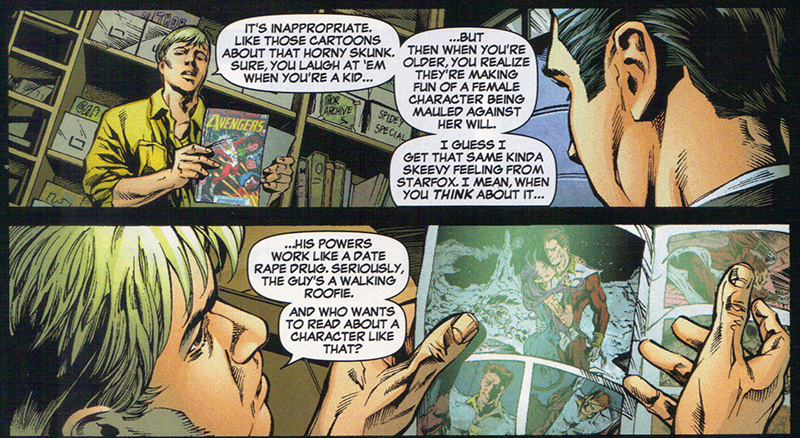

But the art is not enough—at least not by the standard of the first full story-arc (and that seems fair)—to make this series compelling. Perhaps I should not be surprised given Brian Wood’s characterization of the project in an article about the series from USA Today. He says: “I feel like as far as the X-Men go, the women are the X-Men. Cyclops and Wolverine are big names, but taken as a whole, the women kind of rule the franchise.” This could indicate the potential for an interesting take. It brings up the question: why are Cyclops and Wolverine the big names, if the women on the team seem to be the backbone of the franchise? A good series might take up that question more explicitly. Instead, what we get is a series more in line with the second part of his quotation from the news story, “[I]t’s the females that really dominate and are the most interesting and cool to look at. When you have a great artist drawing them, they look so amazing and always have.” Wood gives no indication what makes these women so “interesting,” except perhaps his assertion that they are “cool to look at” and “look so amazing.” When it comes down to it, it is only their appearance as women that makes them interesting in his eyes, not their social position as women in the X-world, or these particular individual characters. They are defined only by their appearance and their sexuality (he makes sure to discuss the potential promiscuity of the characters). Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise given the accusations against Wood by female comics creators, but even if that weren’t the case, I can’t imagine the attitude he displays being all that different from other comics writing dudes, except perhaps that he tries to couch it as liberating to women—as some would say, he is the classic “fake feminist.” Wood seems able to spout the platitudes about how “Most [comics] are written and drawn from a very male point of view, pandering to the largest demographic of readers, and at times with a sexist point of view, with lots of T&A and so on,” but with the inability to see how his own work may fall in line with that tendency as well.

But the art is not enough—at least not by the standard of the first full story-arc (and that seems fair)—to make this series compelling. Perhaps I should not be surprised given Brian Wood’s characterization of the project in an article about the series from USA Today. He says: “I feel like as far as the X-Men go, the women are the X-Men. Cyclops and Wolverine are big names, but taken as a whole, the women kind of rule the franchise.” This could indicate the potential for an interesting take. It brings up the question: why are Cyclops and Wolverine the big names, if the women on the team seem to be the backbone of the franchise? A good series might take up that question more explicitly. Instead, what we get is a series more in line with the second part of his quotation from the news story, “[I]t’s the females that really dominate and are the most interesting and cool to look at. When you have a great artist drawing them, they look so amazing and always have.” Wood gives no indication what makes these women so “interesting,” except perhaps his assertion that they are “cool to look at” and “look so amazing.” When it comes down to it, it is only their appearance as women that makes them interesting in his eyes, not their social position as women in the X-world, or these particular individual characters. They are defined only by their appearance and their sexuality (he makes sure to discuss the potential promiscuity of the characters). Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise given the accusations against Wood by female comics creators, but even if that weren’t the case, I can’t imagine the attitude he displays being all that different from other comics writing dudes, except perhaps that he tries to couch it as liberating to women—as some would say, he is the classic “fake feminist.” Wood seems able to spout the platitudes about how “Most [comics] are written and drawn from a very male point of view, pandering to the largest demographic of readers, and at times with a sexist point of view, with lots of T&A and so on,” but with the inability to see how his own work may fall in line with that tendency as well.

Looking through the list of people who’ve written X-Men comics, I see no women on that list, and while having a woman doing the writing is by no means a guarantee of a good comic, if the women of the series really do dominate it, as Wood would have us believe, then it is beyond time to allow a woman to dominate the series from the writer’s seat for a change. I mean, it’s only been 50 years. Sure, Louise Simonson worked as Claremont’s editor on Uncanny X-Men for four years, and she did get to influence the characters by writing about 60 issues of X-Factor and 30-some issues of The New Mutants, but the flagship title? It has always remained in the hands of men.