This is part of a roundtable on The Best Band No One Has Ever Heard Of. The index to the roundtable is here.

___________

Let’s get this out of the way: this post contains no recorded music. There are no YouTube clips, no media files, nothing ripped from my iTunes library. How frustrating: after finishing this “best band you’ve never heard of” post, you still won’t have heard a thing.

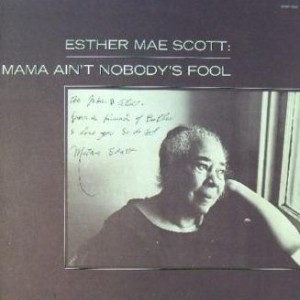

It’s not a sadistic joke, just a matter of fact. Esther Mae “Mother” Scott performed for over seven decades, but she made just one album, at the age of 78. There are only a few copies of “Mama Ain’t Nobody’s Fool” floating around, some of them in archival collections (which is where I heard her for the first time). The reality is that there is still so very much in our musical past that does not exist digitally, and Mother Scott’s music fits in that category. Still, I’ve decided not to let the lack of digital access to her music prevent me from writing about her here.

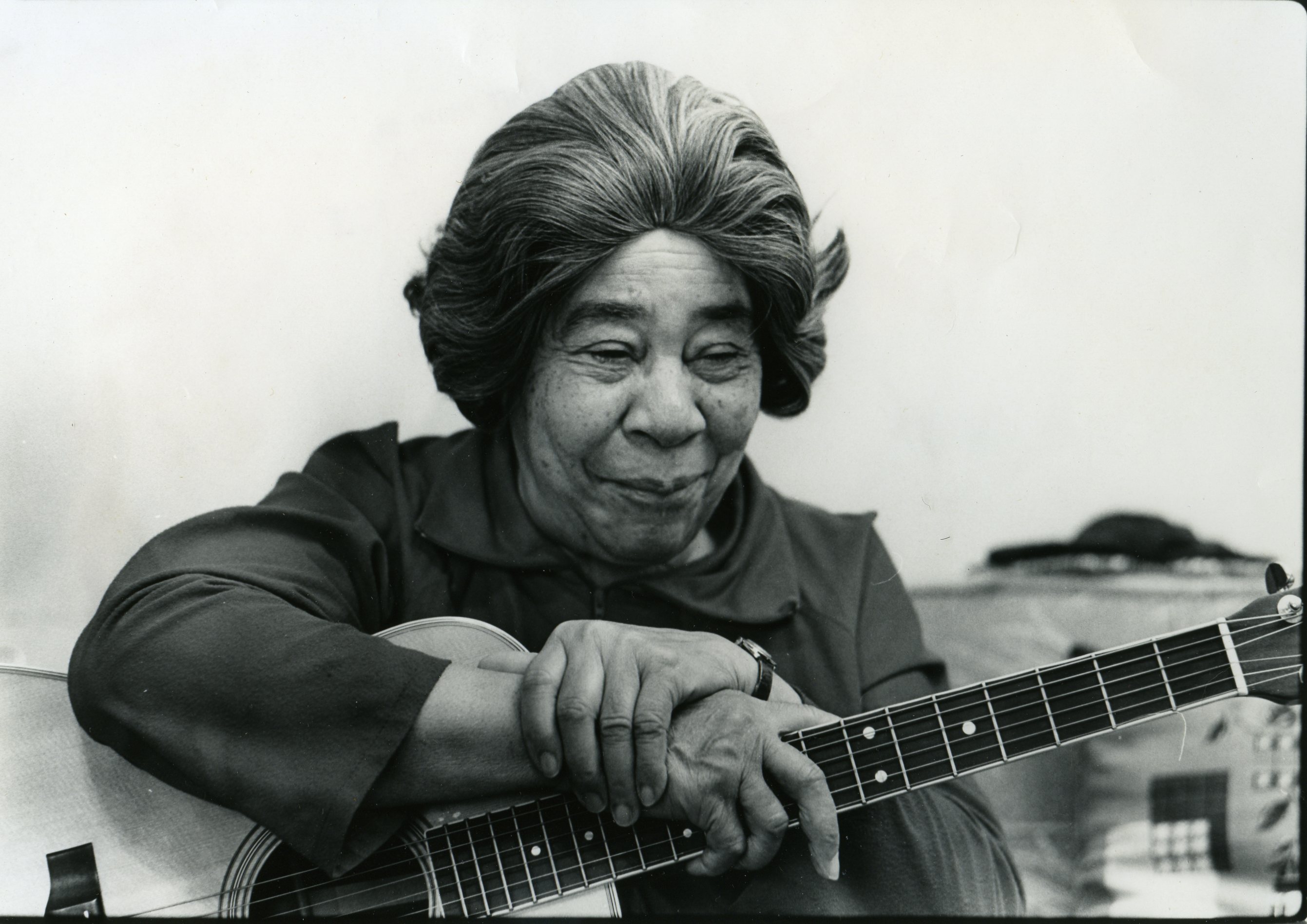

Esther Mae Prentiss was born in 1893 in the Delta town of Bovina, Mississippi. She was a contemporary of better-known musicians, including Gertrude “Ma” Rainey (born 1886) and Bessie Smith (born 1894) and the trajectory of her early life mirrored theirs. Like Rainey and Smith, Prentiss (who soon was to become Scott) left home at an early age—she told an interviewer that she claimed to be 16 when she was actually 14—to join F.S. Wolcott’s Rabbit’s Foot Minstrels, a traveling tent show of musicians, dancers, animal acts, acrobats, and medicine hawkers. Asked to describe her work on the show, which traveled throughout the Mississippi Delta, Louisiana, and other parts of the Mid-South, Scott—whose stage name was “Big Baby”—said, “I’d play and sing and act and lie!” Like Rainey, Smith, and other blueswomen, her personal history blurs the boundaries between singer, dancer, actress, and entrepreneur, for she was all of these things. Life on the touring circuit was hard, but it provided access to the wider world and a sense of freedom and self-determination not provided by agricultural work or domestic service (the two options most available to black women in the South).

I’ve written elsewhere about the importance of the traveling tent and minstrel shows (as have Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff in their amazing book Ragged But Right), and how attending carefully to these shows helps reframe our understanding of early blues. Here’s what the earliest blues was not: a man walking down a dusty road by himself, a guitar slung over his shoulder. The public in the teens and twenties primarily understood blues to be a women’s form, a popular form, and a theatrical form. It is for this reason that Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and, yes, Esther Mae Scott, should be considered the foremothers of blues, a form and a mythology which was later almost entirely turned over to men.

Why don’t we know about Mother Scott the way we know about Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lead Belly, or Son House—or even Rainey or Smith? Though known widely and well as a live performer, Scott made no recordings until very late in life. And when it came time for the largely white male blues revivalists of the 50s and 60s to “rediscover” forgotten legends of blues, their investment in particular narratives of racial authenticity led them not to the commercial, popular, theatrical female performers of the early twentieth century, but to the male agricultural laborers who more clearly fit their image of “authentic” rural folk. Though her work remained unrecognized and unrecorded, Esther Mae Scott was, well into the late twentieth century, a living link with a largely female tradition of blues singing, comedy, and popular entertainment.

Scott retired from show business for the first time in 1941; she left Mississippi, like so many others who were part of the Great Migration, to move to Washington, D.C. She worked as a housekeeper and baby nurse until picking up her guitar again some decades later. As an older woman, she brought her theatricality, her professionalism, and her humor to civil rights campaigns for senior citizens, and the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, one of the highlights of her career.

And about that album (which has a not-yet-famous Emmylou Harris on backing vocals)… “Mama Ain’t Nobody’s Fool” (Bomp Records) shows us just how widely varied the blueswomen’s repertoires were. There are 12-bar blues here, like the “Gulf Coast Blues” Smith made famous. But there’s also a cover of Jimmie Rodgers’ “Blue Yodel No. 1” (here called “T for Texas”), which shows the proximity of “blues” and “country” among traveling tent show and vaudeville performers like Scott and Rodgers, both of whom were from Mississippi. Like her peers, Scott showcased her ability to adapt contemporary popular songs, and produces a swinging “Can’t Buy Me Love,” which imbues the Beatles’ teen-pop hit with the wisdom of a woman who’s lived a long life. Finally, her “Black Jesus/Alleluia” wittily links the domestic labor of her earthly life to the promise of reward in a heaven that belongs to “Black Jesus:” “When I get to heaven, do I enter the back door? Hang up my robe and start scrubbing floors?” “Black Jesus,” like so many of Scott’s songs, links popular, memorable melodies to calls for civil rights that are irresistibly singable. And so while Scott’s music may not endure on countless recordings, her work as a musician, dancer, comedian, and songleader, persists in the less traceable repetition and reinvention of songs sung in churches, around campfires, and recorded by others whose names we do know: Pete Seeger, Lead Belly, Bessie Smith, and Louis Armstrong.

In the late 1970s, Scott was interviewed for the Black Women Oral History Project at Harvard:

http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/45175352

Find more pictures and poetry of Scott’s here: http://esthermaescott.com/