Alternate Title: Barbarians at the Blog!

Back in 2000, the world was a better, simpler place.* The American comics market exemplified this simplicity. It consisted of Marvel superheroes, DC superheroes, Image superheroes, a few dark fantasies from Vertigo, and those Star Wars comics that Dark Horse keeps churning out. Not exactly a broad selection, but perfect for aging nerds who grew up reading superhero comics and watching Star Wars.

But something happened over the past decade. Publishers started producing more comics that had nothing to do with superheroes. Suddenly, there were a lot more horror comics, crime comics, science fiction comics, war comics, and even Westerns (you know something big is going down when Westerns make a comeback). If the comics industry didn’t grow much in size, it at least grew in variety.

Over the next couple months, I plan to see what the American comics market has to offer that doesn’t involve capes and tights. Because I’m interested in what the comics industry is producing at the beginning of the new decade, I’ll only be looking at recent titles, not reprinted material. To keep myself focused, I’m going to organize the books into genres and review a sample of titles. I have no intention of reading and reviewing every title of every genre, so instead I’ll rely upon a complex scientific formula to select titles that are most representative of each genre. The explanation of my method is provided in footnote **. After the reviews, I’ll summarize the state of each genre, looking at both its size in the market and the overall quality of its titles.

I’ll begin with a genre that has had its share of ups-and-downs in the comics market … barbarians! For the sake of clarity, barbarian comics are fantasy stories about muscular men in loin clothes killing shit with swords and axes. Of course, there’s room for variation on this basic model. For example, woman in chainmail bikini can be substituted in for man in loin cloth. But barbarian stories are not simply high fantasy tales; there needs to be a significant amount of violence, sex, and characters who never wear pants (as a counterexample, The Lord of the Rings has some violence but no sex and way too many pants). Also, comics about fantasy strongmen who arrive in the present day and fight crime are not barbarian stories. They’re superhero stories that steal the surface appeal of barbarian stories.

I looked hard for recently published barbarian comics, but I found only about half a dozen titles, four of which I chose to review below. None of these titles were selling well in the Direct Market, but all of the titles had prior storylines collected and sold as trades, so presumably the DM isn’t the only source of sales. Now, onto the reviews…

Conan the Cimmerian #16

Writer: Timothy Truman

Artists: Timothy Truman and Tomas Giorello

Colorist: Jose Villarrubia

Publisher: Dark Horse Comics

Fact: The Cimmerians were a real people who inhabited the region around the Black Sea in the 8th and 7th centuries B.C.

Fact: They didn’t look like Austrian bodybuilders.

Of course, the Conan story has nothing to do with history and everything to do with Robert E. Howard‘s testosterone-fueled fantasies. But Conan isn’t just another masculine power fantasy. He pretty much is THE masculine power fantasy, the epitome of violence, sex, and rugged individualism. And no survey of barbarian comics would be complete without covering the latest iteration of the muscle bound brute who started it all.

I lucked out with Conan the Cimmerian #16, because it’s the beginning of a new storyline. There’s no recap page, but I had no problem figuring out what was going on. Conan somehow landed himself a sweet gig as the military adviser to a hot princess named Yasmela. Conan’s in love with her, but she only has eyes for an exiled prince named Julion, who’s girly compared to Conan. We know he’s a girly man because he does girly things, like giving flowers to girls and using multisyllabic words.

So Conan decides to impress her by doing something stupid, which results in his war band getting ambushed, and then Conan almost gets eaten by a velociraptor (it’s fantasy, not history).

As Conan stories go, this isn’t bad. It has character-driven conflict, Conan is a badass but not infallible, and there’s violence and (implied) sex.

The comic falters on the art. Tomas Giorello does the first seven pages and the final page, and his work is perfectly suited to a Conan book. His backgrounds are lush, and he uses numerous small lines to give more detail to his characters, which would be annoying in a different context, but in a barbarian book it gives the characters a distinctly savage look. But the majority of the comic is drawn by writer Timothy Truman, and his style is far less detailed and far more cartoonish. It isn’t terrible art, but the transition from Giorello to Hutton and back again is jarring, especially in a comic that’s only 24 pages.

Overall, a decent barbarian comic, but not one that entices me to follow the series.

Hercules: The Knives of Kush #1

Writer: Steve Moore

Artist: Cris Bolson

Colorist: Doug Sirois

Publisher: Radical Comics

Reading Hercules, I couldn’t help but take pity on the Nemean Lion. The Nemean Lion was just doing what lions do when a violent Greek showed up and killed him, skinned him, and decided to hear the Lion’s head as a hat.

I spent a lot of time thinking about the Nemean Lion because this comic wasn’t very interesting.

The plot is serviceable: Hercules and his band of misfits arrive in Egypt during a civil war. They decide to work as mercenaries for the legitimate pharaoh, who’s losing the war to his half-brother. It seems that the would-be-usurper has formed an alliance with a sorcerer who leads the titular Knives of Kush.

Unfortunately, nothing else about the comic is the least bit engaging. Most of the characters, including Hercules, lack a distinguishable personality or voice, and in any case they spend spend the entire issue delivering page after page of exposition and occasionally engage in non-witty banter.

The art is also pretty bad. Cris Bolson puts a lot of detail into his panels, but his characters look stiff and plastic. As a result, the fight scenes resemble action figures posed in mid-attack, which robs the violence of any excitement. His sexy women aren’t very sexy either.

Hercules is a hard character to screw up. But he’s also been so extensively ripped off and parodied that creators need to bring something more to the table than just a standard sword and sorcery plot. That’s about all you get here.

Warlord #9

Writer/Artist: Mike Grell

Colorist: David Curiel

Publisher: DC Comics

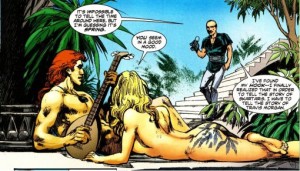

Warlord follows the adventures of Travis Morgan, a man from the regular world who somehow got trapped in the barbarian world of Skartaris. But other than the occasional war, being trapped in Skartaris doesn’t seem like such a bad deal. Morgan has a hot princess girlfriend named Tara and a hot pseudo-girlfriend named Shakira who can turn into a cat. In fact, hot, scantily-clad women are as numerous as trees in Skartaris. And Morgan seems to have embraced the local dress-code because his outfit consists of boots, a helmet, and armored underwear.

Not much happens in this issue, but that may not be a failure in the writing so much as the fact that this is a “down-time” issue. In a superhero comic, down-time issues are normally where characters sit around and whine about their relationships, but in Warlord the characters just have sex. And there is a lot of sex in this issue. Nothing too racy, of course (this is still a DC comic), but Grell manages to include some nice cheesecake. Though the guitar as phallic symbol is a little too obvious.

As an artist, Grell has his share of strengths and weaknesses. His backgrounds are well-designed and his characters can be quite attractive. But his fight scenes lack any real sense of impact, his characters often seem disconnected from the panels they occupy, and panel layout can occasionally be rather confusing.

Problems with the art aside, of all the barbarian comics I read, this seemed the most polished and one with the most depth to its characters and universe. Not surprising, given that Mike Grell created Warlord, and he clearly knows what he’s doing with this book. Unfortunately, this comic has some dense continuity, not just with the previous 9 issues but also with prior Warlord comics. To be fair, there’s a quite a bit of exposition that’s intended to help new readers catch up, but knowing what happened previously isn’t the same as caring. Like so many comics that have been around (off-and-on) for years, Warlord proceeds with the assumption that its readers are already fans, and there’s only minimal effort to show new readers why they should care about any of this.

But I’m curious enough about Warlord that I’ll probably look for the first trade paperback and see whether my opinion changes.

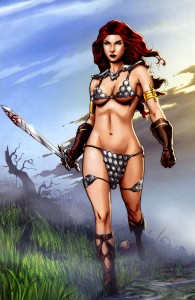

Queen Sonja #1

Writer: Joshua Ortega

Artist: Mel Rubi

Colorist: Vinicius Andrade (*that is an awesome name*)

Publisher: Dynamite

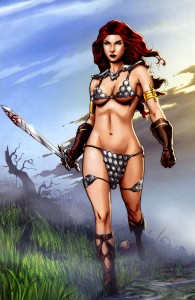

Don’t let the title fool you. This is not a Female Force bio-comic about Queen Sonja of Norway. Rather, this is the sequel to Dynamite’s Red Sonja comic, but there’s no evident continuity with the previous title. As someone who never read a Red Sonja comic, I can appreciate the fresh start.

As the title makes clear, Sonja is now a queen (of Made-up Land), and the comic is mostly a flashback about how she ended up on the throne. Sonja agrees to avenge an old woman’s late husband and recover a family heirloom, and along the way she’s clearly going to come into conflict with an evil empire. There’s also plenty of violence and gore in this comic, in the best barbarian tradition. But the plot and the action (not to mention the one-dimensional characters) are completely overwhelmed by the massive amounts of cheesecake. Every other panel focuses on Sonja’s perfect body and the chainmail bikini that seems perpetually about to fall off.

Now, I don’t have a problem with cheesecake, I just wrote a paragraph praising the cheesecake in Warlord, but in this title the cheesecake was ridiculously excessive. But when I stopped to think about it, the cheesecake is ultimately what this comic is all about. Let’s be honest: the selling point of Red Sonja is not really the violence and it certainly isn’t the plot. It’s a comic about a hot red-head in a chainmail bikini. Either you want to look at a hot red-head in a chainmail bikini, or you don’t. Giving her a more tasteful outfit would only take away the one thing that makes Sonja memorable. And there’s no point in pretending that readers, especially women, are going to be won over by Sonja’s “personality,” or the slim bits of dialogue.

Admittedly, my interest in barbarian comics is that of a casual reader, not a fan, but a monthly comic seems like an expensive way to indulge a fetish for barbarian pin-ups. Still, the current Red Sonja franchise has lasted for over 4 years, so there must be plenty of people out there who like this. And unlike superhero comics, barbarian comics aren’t (or shouldn’t be) marketed towards children, so the cheesecake here isn’t age-inappropriate.

_

State of the Genre: meager. Very few titles to choose from, and most of them lack truly distinctive features that set them apart from the rest. They all satisfy the basic expectations for a barbarian comic (fantasy setting, violence, cheesecake, lack of pants), but only Warlord suggests that it might have something more in content.

The next time I appraise a genre, I’ll try one that’s a bit more robust, maybe horror.

_________________________

*This is not true.