The Blair Witch Project (1999) is the most likely starting point for the “found footage” sub-genre of horror. If you want to nit-pick, the first film to use the found footage concept was the Italian sleazefest Cannibal Holocaust (1980). But the film never pretended that the found footage (filmed by a “lost” documentary crew) was real in our world. Instead, the documentary footage was contained within a narrative that was clearly fictional. The Blair Witch Project, on the other hand, never stopped pretending. Even the marketing campaign (which included a fake documentary on the “legend” of the Blair Witch) passed the film off as real footage of the filmmakers’ last days.

Since Blair Witch there’s been a steady trickle of these films. They are not a new genre so much as a hybrid genre that steals ideas from older horror movies, and combines them with the conceit that the film depicts real events, or at least that the film was produced by individuals who are actually present within the story (usually amateur filmmakers). This means poor lighting, shaky camera-work, and unknown actors who can pass as normal people. But the films still contain the tropes that moviegoers expect from mainstream horror. After The Blair Witch Project (killer in the woods genre) came [REC] and its inferior American remake Quarantine (pseudo-zombie genre), Diary of the Dead (zombie apocalypse genre), Cloverfield (giant monster genre), Apollo 18 (alien genre), and Paranormal Activity (haunted house genre).

But how real is found footage? If I were being stalked by a ghost/slasher/zombie/serial killer/tropical cannibal, the last thing I would do is record my demise for posterity. No offense to my tiny audience, but I don’t give a flying fuck about entertaining you in my final moments. And who in their right mind would waste time recording the ghost or giant monster that’s trying to kill them (as well as the touching romantic sub-plot during the lulls in the violence)? The common defense of the genre is that we live in the Youtube and cellphone camera age, and the genre simply reflects the fact that we are saturated with amateur video. But amateur footage of protests, crimes, terrorist attacks, etc. tends to be brief, incompetently filmed, and rarely has anything resembling likable characters or a plot. In other words, actual amateur video bares no resemblance to the professionally crafted narratives that lurk underneath the “found footage” concept. And there’s the little fact that it’s impossible to record video of ghosts, zombies, or giant monsters because those creatures don’t exist.

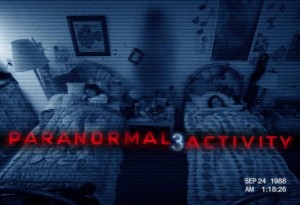

And yet audiences eat this shit up, and I’m right there with them. My favorite set of films in the genre is the Paranormal Activity franchise. The first Paranormal Activity is not particularly innovative. It’s cut from the exact same cloth as a thousand other haunted house movies, and it’s at least as campy as anything starring Vincent Price. But I found it scarier and far more entertaining than The Haunting, Amityville Horror, The Others, or any other haunted house movie that exists in a fictional universe. Paranormal Activity 3 is the perfect example of the genre. The entire premise is ridiculous: a demon is terrorizing a family in 1988, and the dad just happens to be an audio/video expert who rigs his house with video cameras and always walks around with a massive camcorder. The film is unabashedly cheesy, and even includes the old ghost-under-the-sheet gag. But it’s great! The simple plot sucks you in and the old-fashioned scares still work. The viewer quickly forgives the implausibility of a man walking around with a camcorder all the time, because how else would there even be a movie?

It’s not the phony realism that matters, but how that realism connects the audience with a familiar narrative. To put it another way, found footage works not because we belong to the Youtube generation, but because we belong to the Real World generation (youngsters can replace Real World with Survivor or Real Housewives of Who Cares or whatever reality TV series floats your boat). So-called reality TV is quite fake. Real people are encouraged to behave in unnatural ways for the sake of our entertainment. They are less inhibited, more reckless, and generally stupider when in front of the camera. Then a team of professional editors and writers crafts an artificial narrative from countless hours of random shit caught on tape. Through this process reality TV creates the ultimate illusion – that normal people are actually interesting to watch. Normal people can have exciting singing careers, or scheme to win a million dollars, or have lives filled with catfights, hot tub sex, and soap opera drama.

The found footage genre works in much the same way. The pretense that the film is real isn’t so much about fooling people but in bringing the audience further into familiar narratives that they love. The shaky camera and unknown actors create an illusion of reality. Scary and exciting things don’t just happen to movie stars. They can happen to normal people, just like you or me! But this illusion of reality is plastered over a conventional genre film. So the scares are structured in a narrative format that we instantly recognized and appreciate. In movies and in “real life,” a ghost wouldn’t reveal itself right away, but would instead spends several days doing little things to build up the suspense. It would be a disappointment if the “real” haunted house experience lacked the requisite tension and cheap thrills. After all, what’s the point of being haunted by a demon if he doesn’t even do it right?