So that hatefest, pretty amazing right? Fun, fun. Let’s palette-cleanse the hate with some love.

I wish there were more pulp manga criticism in the English-speaking world, maybe I’m greedy. The enthusiasm is there, but the western fanbase for manga is its own separate animal, intersecting very selectively with the western comics fanbase as a whole. Comics, around these parts, is already a medium encumbered with a lot of self-loathing baggage (“This comic has proven itself a worthy piece of literature because it bears only a passing resemblance to a comic book, having evolved to the Higher Art™ of being comparable to paintings or novels, because me hate comics”) and manga receives the same treatment, if not worse, due to having to pass the same threshold of judgement twice. Manga considered worthy of fair dissection is generally the stuff considered the seminal work of the fundamental, albeit tirelessly namedropped, Tezuka, Tatsumi, Tezuka, Koike, Tezuka, Tezuka, and so forth.

This leaves pulp manga in a curious place. We aren’t talking about it enough. (Not that there’s ever ‘enough’ for me)

Which is odd, because you wouldn’t know it. Especially considering the sheer volume of how many comic book artists across the board, young ones in particular, grew up with genre manga. The influence manifests itself in the stylistic quirks and narrative framing many modern cartoonists employ in their own work. For so many western readers, manga provided an enormous range of reading material, filling in the gaps where shops full of superhero comics left wanting. Readers who grew up with stuff like Berserk and Dorohedoro are eager to unearth foundational genre manga that isn’t only Tezuka, and resonates with them in a familiar way. People who spent their pimplier years eating up Utena and Sailor Moon are tickled to find the studly women in Rose of Versailles, people into dense scifi will dig the romantic Matsumoto space operas, and no-good briny punks like me get into Devilman.

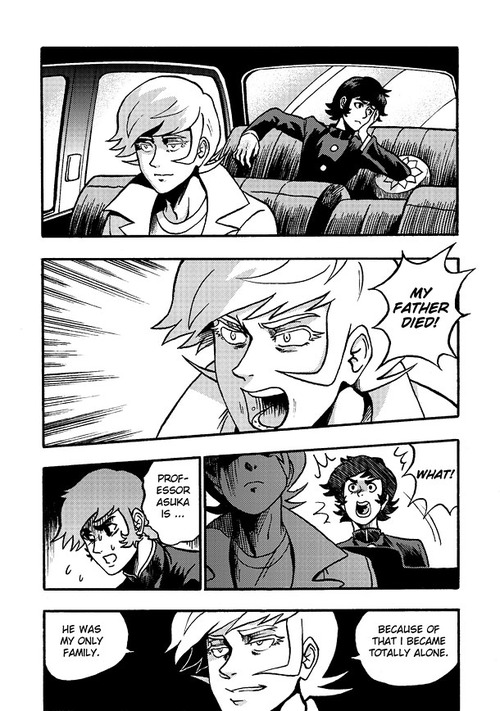

A resurging interest in Devilman-creator Go Nagai’s work yields these fabulous re-paneled versions of the Devilman page in which Ryo recalls the loss of his father. The artists who produced these are as follows: Rachel Morris, Tara S., more can be seen here

A resurging interest in Devilman-creator Go Nagai’s work yields these fabulous re-paneled versions of the Devilman page in which Ryo recalls the loss of his father. The artists who produced these are as follows: Rachel Morris, Tara S., more can be seen here

The 1972 horror manga Devilman is arguably Go Nagai’s most iconic series and most iconic character. It generally doesn’t receive as much recognition here as Nagai’s super robots, and though I could talk super robot all day, many of those comics have not aged especially well. Devilman’s influence on other comics and animation is sprawling in ways that can’t be covered in one article written by one dick-for-brains Rory D. It has affected abstraction in manga ever since its initial run, and has been reprinted several times, given countless bizarre spinoffs, an upsetting PSX game, all that good stuff. The entire series has never been formally licensed in America, only a few issues having been published in the states under Glenn Danzig’s comics joint, and the Kodansha bilingual volumes are a little harder to procure. The only easily accessible finished translations are fan-translations found online, which may be a turn-off to purists and may be totally desirable to people with a special kind of appreciation for those 90s Mangavideo dubs where everybody says ‘fuck’ and ‘shit’ like a million times.

We are introduced to Akira Fudo, a meek high school student with no apparent desire to impress others via manufactured aggression, the way his peers do. Within the first few pages he and his platonic lady friend Miki are threatened by three mincing goons. Akira is helpless to stop them until his childhood friend Ryo Asuka shows up, goes ham, and scares the goons off with a rifle. It’s at this point we’re given a microcosm of the Akira’s entire character arc: Akira describes himself as a pacifist, chiding Miki when she threatens these same dudes with a knife, and yet he’s drawn immediately to Ryo’s overt display of intimidation, and follows him without question, leaving Miki behind to stand around and gawk. When we reach the spooky Satan mansion-slash-hedonistic teen orgy nightclub, Ryo explains that because Akira is pure of heart, he can command satanic powers and bloody up bad guys, all while conveniently retaining his humanity. This is the payoff. This is what young boy readers look forward to seeing, to open the box of curiosity, and wield that sort of power without consequence.

Alright, full disclosure: I am a big stupid meathead. I love violent comics unapologetically, I love satanic metal and Fulci movies, and I probably spraypainted a wiener onto a wall once. I like a lot of things I would otherwise totally harp on if I were to actually sit down and talk about them. I do not think even the most schmaltzy, unyielding violent comics will turn anybody into an amoral weirdo on their own. However, I still explore the subject of violence in fiction and the contention therein regularly, it’s unavoidable, as my own work is so heavily influenced by splatter horror. Because the most vocal opponents to violence in fiction are often the most sanctimonious and ignorant, those of us who are really into that sort of thing hand-wave many opportunities to explore our relationship with violence in artwork and in storytelling.

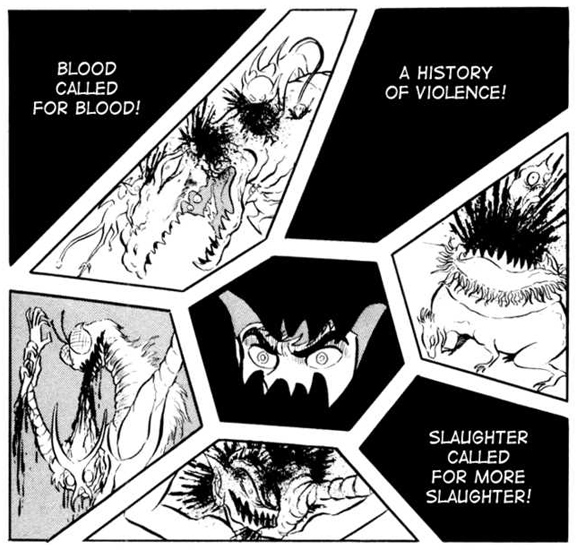

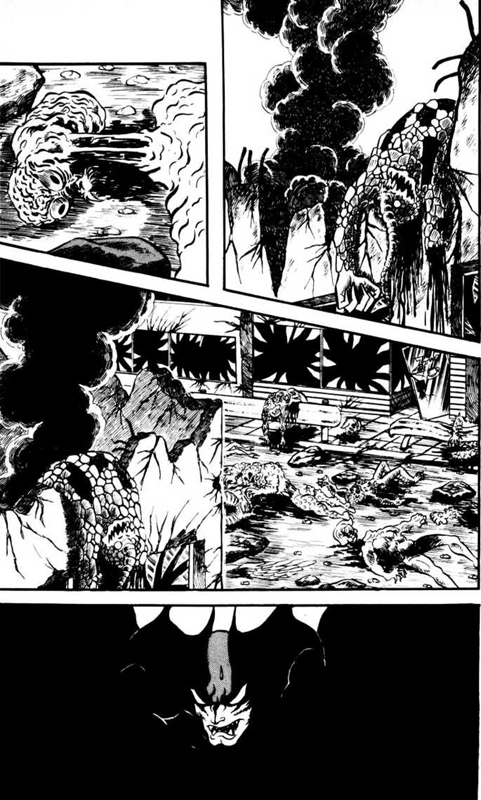

Nagai’s artwork contorts everything, from human beings to the tokusatsu-Bosch-stylized demons, into elongated grotesqueries. The facial expressions are distorted the point of resembling no easily recognizable human emotion, and yet they’re intensely descriptive of the emotive quality in each panel. The gore and dismemberment are not depicted with the same indulgence or attention to detail you may find in many of the comics Devilman would go on to influence. Instead, it plays around with the abstraction of violence, Nagai’s expressionistic viscera is so divorced from reality that it doesn’t feel like a voyeuristic journey through the reader’s expectations of fantasy violence. Not unlike the bellicose swaths in Goya’s Black Paintings, the quality of Nagai’s linework brings out the genuine horror in Devilman’s more emotionally charged sequences of brutality. Even in the safely removed fantasy world, there is a palpable disgust for violence in the visual language of the world itself, more than something like Gantz which wallows in fetishized, baroque torture porn. Not to set a false dichotomy since there are plenty of things I enjoy that are saturated with the latter, but the question to consider: Do we read horror comics to consider the idea of violence, or do we do it to to see violence?

To say brutality is a common thematic element in all of these comics would be an understatement warranting a captain-obvious side-eye. We read contemporaries like Berserk and Hellsing and Blame to see a bunch of faceless dudes and demons get straight murdered. The fetishization of violence is an engendered trope in pulp manga, as it is in all comics (and all things) presenting violence as a selling point. When Devilman first ran, it was so controversially gory that Nagai would sometimes go on vacation to places where no one could find him and still be greeted by mobs of angry mothers upon landing at the airport. It’s long since passed the point of taboo; in order for violence to be interesting, it needs hierarchy and purpose. Hierarchy and purpose delivers through to the end, on the simple premise that Akira retaining his humanity opens the channels of cruelty moreso than if he were one of the expendable crony demons.

Miki is repeatedly endangered as a vehicle for Akira’s development. Out of all the possible scenarios in which Miki could be left vulnerable to be attacked by demons, electing to have her attacked while she’s bathing evokes the familiar gender trouble present in many forms of pulp horror. This is one area where Devilman falls flat on its face. I think there is something to be said of the way Akira’s descent into hard-hearted depersonalization affects the way he treats Miki, but it’s muddied by the fact that she barely registers as a character. The objectification of a woman as a symbol of peace would warrant its own separate article. The ‘monster of the week’ format doesn’t feel like an aimless excuse to peddle more monsters, each monster Akira fights whittles his grasp on his passive nature and other ‘desirable’ human traits a little more. In a particularly gruesome story, Akira blames himself for the death of a young child, and a turtle demon taunts him and feeds off of his wrathful despair as a result, leaving him worsened by the time he’s killed the creature.

In many power fantasies, goring up objectively evil something-or-others without consequence to serve a greater good is something often unquestioned. A cyber-cop shoots a cyber-demon point blank in the face and we move on to the next one. But when Akira is possessed of Devilman qualities, even when not transformed, he becomes crass, emotionally distant, and aggressive. In order to transform, he must lose all reason, giving full reign of his mind to the side of him that was always a senseless destroyer, rather than this side of him being something summoned in the sabbath amidst all the hippie-stabbing. Returning to the first act of the story, when Ryo launches into that long, slow-brewing exposition about the demons, he’s essentially giving Akira an elaborate justification for setting free his id.

The final arc spirals into meandering chaos in which humans callously torture and dissect captured devilmen, nuclear weapons flatten most of the known world, and the identity of Ryo Asuka is revealed. The ending is notoriously ambiguous. No one is rewarded for what has transpired. It’s a counterpoint to the power fantasies in shonen manga that is enjoyable through to the end. Devilman incorporates fun, playful tokusatsu aesthetics against a morally dense cautionary tale.

Anyway, damn, I love Berserk too, I wanna talk about Berserk. ’till next time?