Defining the concept COMIC has, perhaps, been the cause of more ink spillage and deforestation than any other single theoretical topic in comics studies. Interestingly (and rather predictably), work on this topic has loosely followed the same trajectory as earlier attempts to define the concept ART.

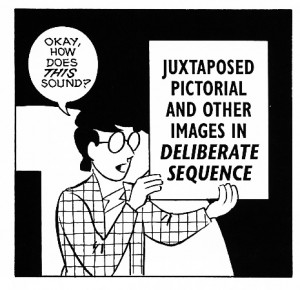

First, we have formal, aesthetic, and/or moral definitions of comics roughly paralleling traditional, pre-twentieth century definitions of art. Nontable examples include David Kunzle (The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825, 1973), Will Eisner (Comics and Sequential Art, 1985), Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 1993), David Carrier (The Aesthetics of Comics, 2000), and Thierry Groensteen (The System of Comics, 1999/2007). Comparisons are easily made to Plato, Kant, and even John Dewey’s accounts of the nature of art. But, just as the second-half of the twentieth century saw a widespread rejection of any such account of the nature of art that entails that an object is an artwork solely in terms of some properties (whether formal, aesthetic, or moral) that inhere in the object itself, during the early twenty-first century comic studies has seen a similar turn away from formal definitions in favor of other approaches. Interestingly, the three main alternative approaches to defining comics match almost exactly the three main approaches found in earlier, twentieth century work on defining art.

First, we have formal, aesthetic, and/or moral definitions of comics roughly paralleling traditional, pre-twentieth century definitions of art. Nontable examples include David Kunzle (The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825, 1973), Will Eisner (Comics and Sequential Art, 1985), Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, 1993), David Carrier (The Aesthetics of Comics, 2000), and Thierry Groensteen (The System of Comics, 1999/2007). Comparisons are easily made to Plato, Kant, and even John Dewey’s accounts of the nature of art. But, just as the second-half of the twentieth century saw a widespread rejection of any such account of the nature of art that entails that an object is an artwork solely in terms of some properties (whether formal, aesthetic, or moral) that inhere in the object itself, during the early twenty-first century comic studies has seen a similar turn away from formal definitions in favor of other approaches. Interestingly, the three main alternative approaches to defining comics match almost exactly the three main approaches found in earlier, twentieth century work on defining art.

First, there is the outright rejection of either the necessity of, or even the possibility of, a definition of the concept at all. Notable examples of such an approach in comic studies include Samuel Delaney (“The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism”, 1996), Douglas Wolk (Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean, 2007), and Charles Hatfield (“Defining Comics in the Classroom, or the Pros and Cons of Unfixability”, 2009). The connection to Morris Weitz’s (and others’) Wittgensteinian rejection of definitions of art, and his embrace of the “open-endedness” of art, is obvious.

First, there is the outright rejection of either the necessity of, or even the possibility of, a definition of the concept at all. Notable examples of such an approach in comic studies include Samuel Delaney (“The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism”, 1996), Douglas Wolk (Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean, 2007), and Charles Hatfield (“Defining Comics in the Classroom, or the Pros and Cons of Unfixability”, 2009). The connection to Morris Weitz’s (and others’) Wittgensteinian rejection of definitions of art, and his embrace of the “open-endedness” of art, is obvious.

Next we have historical definitions – those accounts that locate the “comicness” of comics in the historical role played by particular comics, and in the history that led to their production (and, perhaps, in intentions, on the part of either creators or consumers, that a particular object play a historically appropriate role). One notable example of an historically-oriented approach to the definition of comics is to be found in Aaron Meskin’s work (in particular, in the concluding remarks to “Defining Comics” 2007, which is otherwise rather hostile to the definitional project). Meskin’s comments (and likely any other account along these lines, although this seems to be the least developed of the options) owes much to Jerrold Levinson’s historical definition of art, whereby an object is an artwork if and only if its creator intends it to be appreciated in ways previous (actual) artworks have been appreciated.

Next we have historical definitions – those accounts that locate the “comicness” of comics in the historical role played by particular comics, and in the history that led to their production (and, perhaps, in intentions, on the part of either creators or consumers, that a particular object play a historically appropriate role). One notable example of an historically-oriented approach to the definition of comics is to be found in Aaron Meskin’s work (in particular, in the concluding remarks to “Defining Comics” 2007, which is otherwise rather hostile to the definitional project). Meskin’s comments (and likely any other account along these lines, although this seems to be the least developed of the options) owes much to Jerrold Levinson’s historical definition of art, whereby an object is an artwork if and only if its creator intends it to be appreciated in ways previous (actual) artworks have been appreciated.

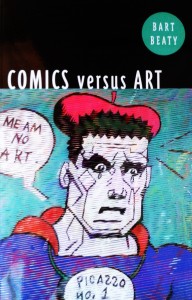

Finally, we have institutional definitions, which take something to be an comic if it is taken to be such by the comics world. The primary proponent of something like an institutional view within comic studies is Bart Beaty (Comics versus Art, 2012). Such views obviously owe much to similar, earlier approaches to the nature of art due to Arthur Danto, George Dickie, and others. Of course, one of the primary challenges here is to determine what counts as the “comics world” in a way that is informative and not viciously circular (i.e., an account where the comics world is not defined merely as those of us who take comics seriously).

Finally, we have institutional definitions, which take something to be an comic if it is taken to be such by the comics world. The primary proponent of something like an institutional view within comic studies is Bart Beaty (Comics versus Art, 2012). Such views obviously owe much to similar, earlier approaches to the nature of art due to Arthur Danto, George Dickie, and others. Of course, one of the primary challenges here is to determine what counts as the “comics world” in a way that is informative and not viciously circular (i.e., an account where the comics world is not defined merely as those of us who take comics seriously).

Thus, the work on defining comics has closely mimicked earlier debates about the definition of, and nature of, the larger category of art (presumably, all, most, or at least typical comics are artworks – even if possibly bad artworks – solely in virtue of being comics). This much seems undeniable, but it also seems somewhat problematic. After all, sticking solely to approaches and strategies that appeared plausible when used to define art is only a wise strategy if we have some sort of prior conviction that the properties and relations that make an object an artwork (i.e. that explain the artwork/non-artwork distinction) are the same properties and relations (or at the very least, the same kind of properties and relations) that make an object a comic (i.e. that explain the comic/non-comic distinction). And to my knowledge no argument has been given that this is the case. As a result, it behooves us to ask if comic studies has been too traditional, and too unimaginative, in this regard. Isn’t it possible that we could be convinced that there is an adequate definition of comics, but also convinced that such a definition should look very different from extant attempts at defining art (i.e. it would take very different kinds of factors into consideration)? And, more to the point, isn’t it possible that such an attitude could be correct? If so, then the close parallel between work on the definition of comics and work on the definition of art seems unfortunate, since it seems to ignore this possibility in favor of recapitulation of past history.

Thus, the work on defining comics has closely mimicked earlier debates about the definition of, and nature of, the larger category of art (presumably, all, most, or at least typical comics are artworks – even if possibly bad artworks – solely in virtue of being comics). This much seems undeniable, but it also seems somewhat problematic. After all, sticking solely to approaches and strategies that appeared plausible when used to define art is only a wise strategy if we have some sort of prior conviction that the properties and relations that make an object an artwork (i.e. that explain the artwork/non-artwork distinction) are the same properties and relations (or at the very least, the same kind of properties and relations) that make an object a comic (i.e. that explain the comic/non-comic distinction). And to my knowledge no argument has been given that this is the case. As a result, it behooves us to ask if comic studies has been too traditional, and too unimaginative, in this regard. Isn’t it possible that we could be convinced that there is an adequate definition of comics, but also convinced that such a definition should look very different from extant attempts at defining art (i.e. it would take very different kinds of factors into consideration)? And, more to the point, isn’t it possible that such an attitude could be correct? If so, then the close parallel between work on the definition of comics and work on the definition of art seems unfortunate, since it seems to ignore this possibility in favor of recapitulation of past history.