This is part of a roundtable on The Best Band No One Has Ever Heard Of. The index to the roundtable is here.

_____

The Music Machine were —

Sean Bonniwell – vocals, guitar

Keith Olsen – bass

Ron Edgar – drums, vocals

Mark Landon – lead guitar

Doug Rhodes – organ, flute, vocals

I’m going to say it again – the “Canon” means nothing. Not in comics, not in literature. And certainly not in music.

There are the little demolitions. The knocks, the craters, the crumbling walls. But it’s not just the Harold Blooms of the world that hang onto the idea, however stupid, that popularity can ever be indicative of quality, that, in the end, in matters of taste, history is always right.

A simple demonstration.

What was the fiercest band of the mid to late sixties “garage rock” explosion? The smartest songs? How about the most adventuresome?

Ever heard of the Music Machine?

No biographical summary of mine would ever be equal to the writing of Richie Unterberger, who interviewed Music Machine singer/songwriter Sean Bonniwell for his 1998 classic book Unknown Legends of Rock and Roll. So for a more thorough overview of the band’s history, pick up a copy of the book, or check out a full transcription of Unterberger’s interview with Bonniwell here.

But really, the songs and performances are their own justification.

The Music Machine hailed from Los Angeles, California, and were formed out of the trio The Ragamuffins. Bonniwell, him of the tough songs and gruff voice, was a graduate of folk quartet The Wayfarers, who released three LPs for RCA in the early 60’s. Listening to those recordings now, it’s hard to imagine the sounds to which that sweet voice would be twisted.

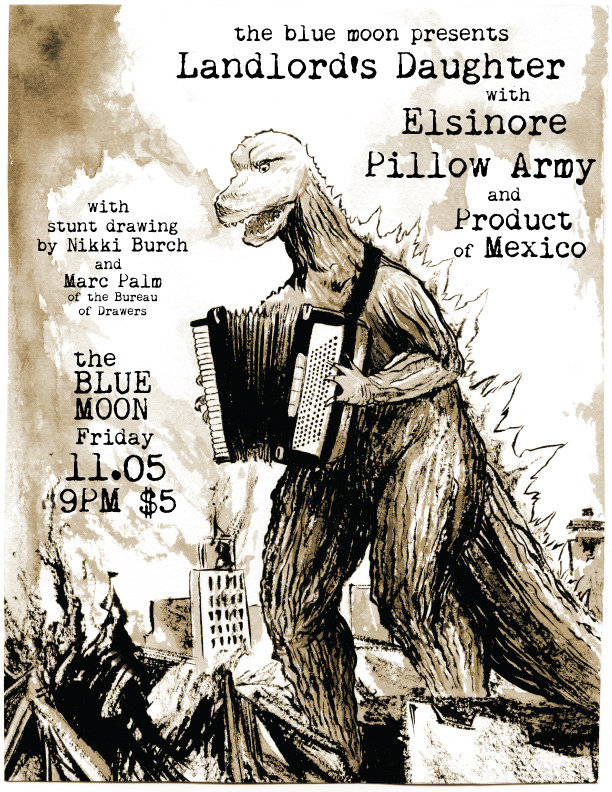

Driven by Bonniwell’s taut songwriting and unhinged voice, the band rose to prominence in the L.A. rock and roll scene and spilled over nationally, scoring a top 20 hit with “Talk Talk,” their scattered, stabbing first single. Like all of the greats, they were discovered in a bowling alley, performing continuous, uninterrupted 90 minute sets for their attentive fans and, presumably, bewildered bowlers. These days, they’re primarily known as “that band” that future Fleetwood Mac producer/engineer Keith Olsen got his start in. (It’s him playing the mean detuned bass guitar on these recordings. He also designed and built the fuzz boxes used by the band.)

At this distance, what you might hear in the Music Machine is really dependent on your own familiar frames of reference. For 60’s popular music enthusiasts, what you have in this soup is essentially a smart, violent Iron Butterfly on speed instead of downers. (A glance at the relevant time lines will tell you which direction this influence lies — the L.A.-via San Diego band Iron Butterfly released their debut album in 1968, two years after the national success of the Music Machine’s “Talk Talk.”) As this comparison might suggest, as much as the “proto-punk” label has been thrown at the Music Machine, it’s perhaps “proto-prog” that’s most present in the arrangements, specifically the segmented nature of the instrumental hand-offs. The songs are rarely constructed by block chords moving around the neck of the guitar – rather, the unusual, doomy chords are suggested by interlocking melodic lines carried by multiple instruments, each staying within its own narrowly defined frequency range.

In the above, “Talk Me Down,” and “You’ll Love Me Again,” you’ll hear the same arrangement sensibilities, stop-start dynamics, gruff then shrieking vocals, wordless screams and pseudo-James Brown mannerisms and funky bass with roller-rink Farfisa organ skating along atop. The line up of the band that recorded (and apparently, endlessly rehearsed) these songs didn’t last long — breaking up sometime in 1967, less than two years into the life of the band. They were, it is said, plagued by bad luck, negligence, short-sightedness, and mismanagement at every turn. And yet, somehow, they managed to squeeze out at least a dozen perfect songs, even if a real full-length statement eluded them.

It’s a fate that could easily have met their contemporaries, Love, or The Zombies, both bands which had tremendous early success with singles that were just indications of the greatness to come, both of which managed to put together transcendent full-length albums before retiring to that great rock and roll second-hand shop in the sky– Forever Changes and Odessey and Oracle, respectively.

But in The Music Machine, we just have those scattered singles, two-minute angry screeds against, what, exactly? Girls. Loneliness. The human struggle for life in a hostile, hateful world of selfish pursuit and gluttonous predation? Complete with horrifying duck calls? Hell yes!

What’s that? You love that terrifying song, but you’d much rather hear it whilst watching the band limply mime the tune? And you’d really like them to be introduced by Casey Kasem? Here you go! Happy to oblige!

What happened to the Music Machine is almost too mundane to summarize. Dissatisfaction. Too little money, too many ways to split it. Exploitation and exhaustion. Too many bowling alleys, not enough nights in the studio. Regardless of the details, they went the way of any great group, leaving, unfortunately, with their ultimate promise unfulfilled.

But oh, what wonderful remains.

You can purchase the entire Music Machine catalogue in two meticulous releases from Big Beat– The Bonniwell Music Machine and the Ultimate Turn-On. If you’ve enjoyed these clips, you’ll love the heck out of these reissues.

It’s an interesting mental exercise to imagine future music enthusiasts digging through the past decade of music, looking for hidden gems of the era, unknown or forgotten bands of that time period. In the case of the Music Machine, they had the serious advantage of lots of regional exposure, hell, of a national hit, even if the trick wasn’t repeated. And even though the rest of their catalog was obscure, the flag, the signal flare, was there. “Here we are. Come listen.”

What hope, exactly, does a band have today?

The bowling alleys, the bars of listeners, the VFWs, the dance halls, the venues, all gone, as is regional radio. All the ways a band had to make themselves known to their neighbors. And so even while recording equipment gets cheaper and cheaper, cheap instruments better and better, the audience continues to shrink. What brave soul would wade into that sea of unfiltered musical content in an attempt to extract the unknown gem?

I don’t envy them the attempt.

I’ll leave you all with two last songs — “In My Neighborhood,” a Music Machine novel in two minutes, and a track from the much-maligned and almost completely invisible Sean Bonniwell follow-up to the Music Machine, which turns a more nostalgic eye toward the past, in retreat from the present.