This is the second part of a two part essay. The first part is here.

______________

Reconstruction 3: Daddy’s Little Girl

Cooke’s campaign to reconstruct Watchmen into a conventional male-affirming narrative continues in his four-part Silk Spectre series with artist Amanda Conner. A series based on Laurie has the potential to be very interesting, since Moore’s handling of her character has often been cited as a weakness.[i] Yet, while there is validity to the criticism that Laurie tends to be overshadowed by the men around her, there has been too little attention paid to how her characterization functions as a critical commentary on comic conventions.

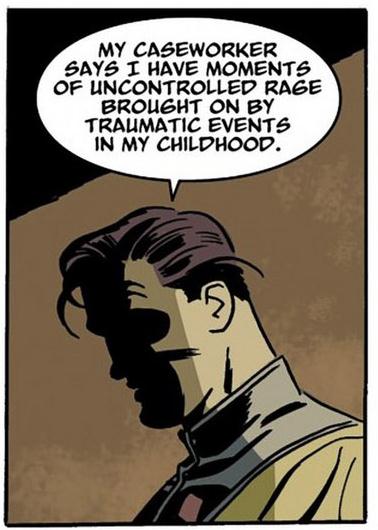

First, it’s unfair to suggest that Moore’s handling of Laurie is completely unoriginal: nearly three decades after Watchmen, there still aren’t many superheroines who fit the description of a thirty-five-year-old, sexually active, cynical, swearing, hard-drinking, puking, chain-smoking ball-breaker (Figure C1).

Second, too many critics have unjustly assumed that Laurie isn’t important enough to warrant analysis (e.g. Klock 65-66). Critics have been quick to recognize the male characters as displacements of various comic book archetypes. There is no reason why this analysis shouldn’t apply to Laurie as well. Like her male peers, Laurie can be read as a deconstructed version of an iconic superhero: William Moulton Marston’s Wonder Woman.[ii]

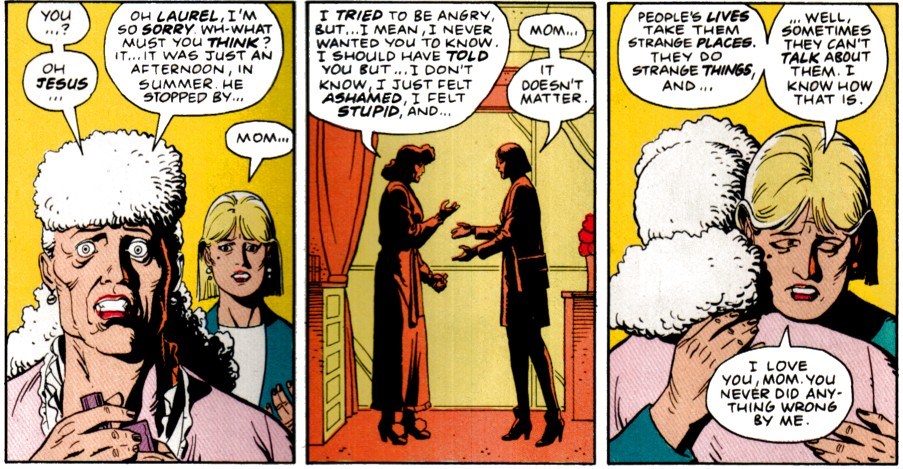

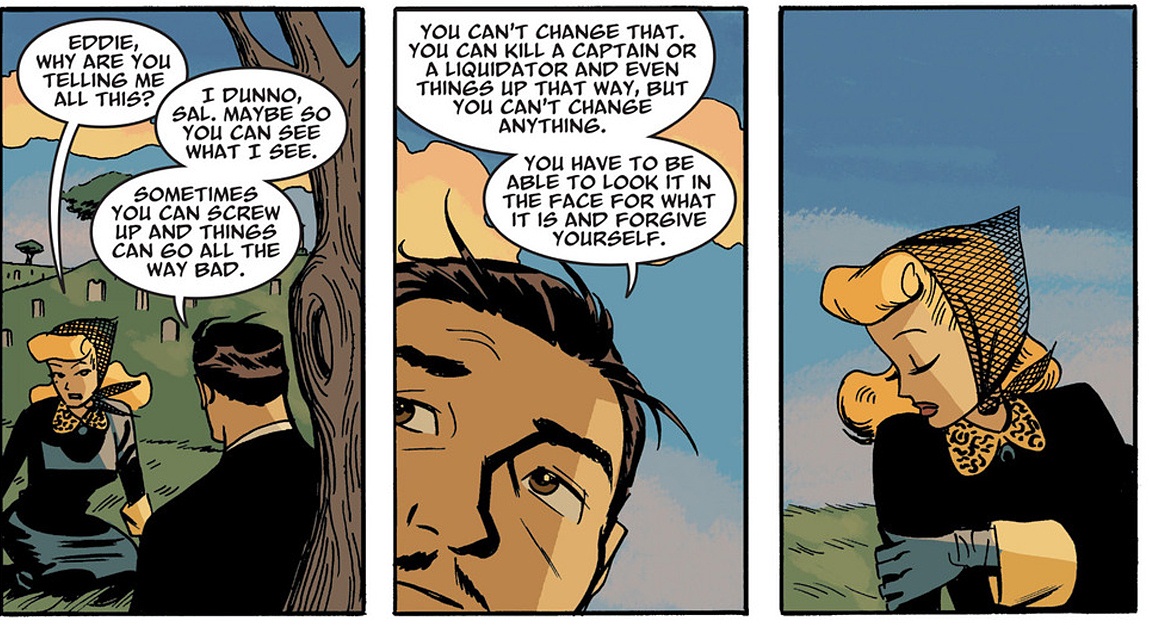

Marston offered a feminist empowerment fantasy in which a powerful heroine is moulded from clay by her mother as a symbol of female redemption from male violence.[iii] Moore deconstructed this fantasy by muddying the heroine’s origin and drawing out the physical, emotional and psychological consequences of rape and abuse. But the deconstruction isn’t about whitewashing male violence or disempowering women. Rather, it is about offering a down-to-earth, non-escapist form of empowerment. In the real world, heroism rarely comes from magical power, divine intervention and ass-kicking antics. It’s more likely to come from tolerance, compassion and forgiveness (Figure C2).

Lacking Diana’s lasso of truth, Laurie finds out a devastating truth which fractures her personal identity and challenges her most cherished beliefs. But rather than demanding heroic perfection, Laurie’s greatest strength turns out to be her compassionate acceptance of human imperfection. Laurie claims Dan as her man, not because he is the most powerful hero in the world, but because he is a decent guy who loves and appreciates her.[iv] She reaches out to Sally, not because she condones rape, but because Sally’s sufferings have made Laurie appreciate all the more everything that her less-than-heroic mother has done for her. She forgives Eddie, not because he deserves forgiveness, but because Sally still loves him and love must be stronger than hate. Out of her parents’ messed-up union, Laurie emerges as a strong, mature, compassionate woman, a true “thermodynamic miracle”.

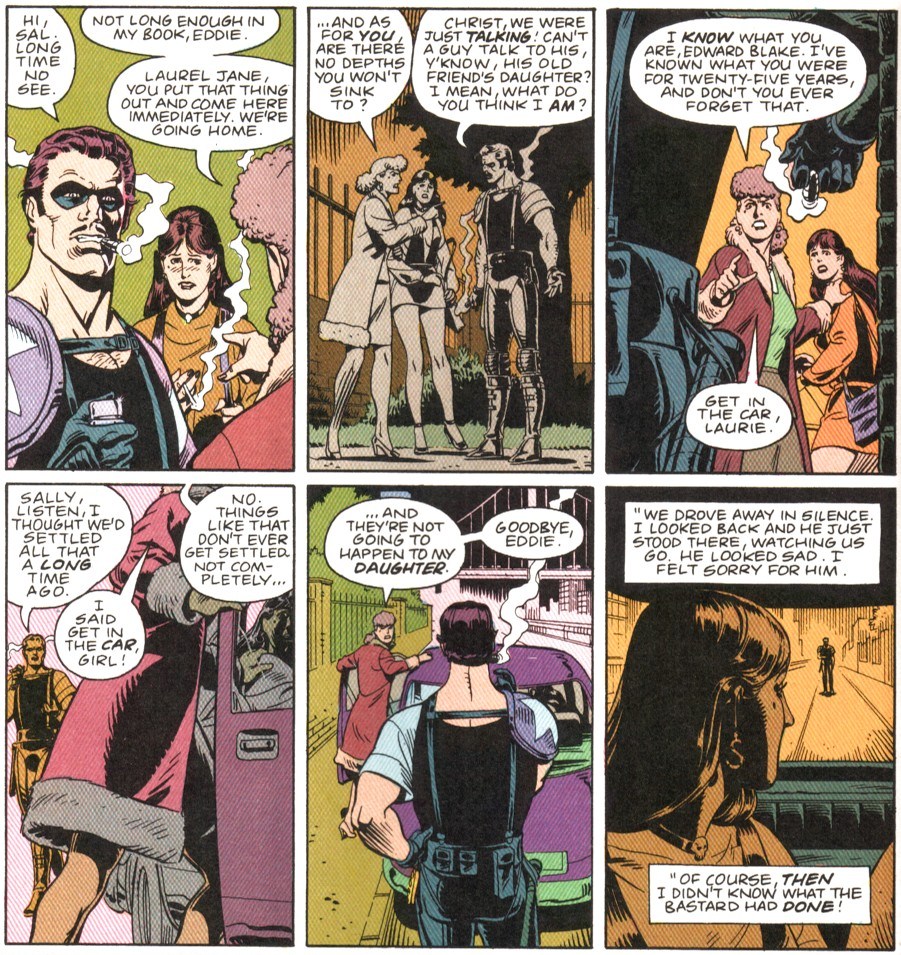

In Silk Spectre, Cooke and Conner attempt to offer a backstory about Laurie’s teenage years. Their story has two main strands: Laurie’s escape from home to join the “summer of love” with her boyfriend, Greg, and her crusade against an evil drug syndicate targeting impressionable youths.[v] Cooke’s decision to frame Laurie’s story as a rebellion against Sally is especially worthy of comment. In the original, Sally’s and Laurie’s relationship gives a rare and important focus to women and rebuts the criticism that the female characters are only relevant in terms of how they relate to the male characters. Moore deconstructed the utopianism of Marston’s all-female Paradise Island by presenting a prosaic scenario in which women might find themselves isolated from men: in the house of a single mother raising an only daughter. In creating this mother-daughter relationship, Moore subjected the comic book assumption that women enjoy fighting crimes in sexy outfits to a much-needed reality-check[vi]—Laurie hates being a superhero and did it mostly to please her mother—but he also used the characters’ motivations and conflicts to offer a humane redefinition of heroism. It is Sally’s sense of weakness and shame that makes her determined to bring Laurie up to be strong and courageous. Sally is able to do this all by herself (in her row with Larry, she tells him: “[D]on’t you worry about [Laurie’s] future. That’s taken care of” (IX.7))—and she did it so well that she dreaded the day when Laurie would find out the truth and expose her as a weakling and hypocrite. That Laurie’s greatest act of heroism should be her compassionate acceptance of Sally’s lack of heroism is one of the touching ironies of their relationship.

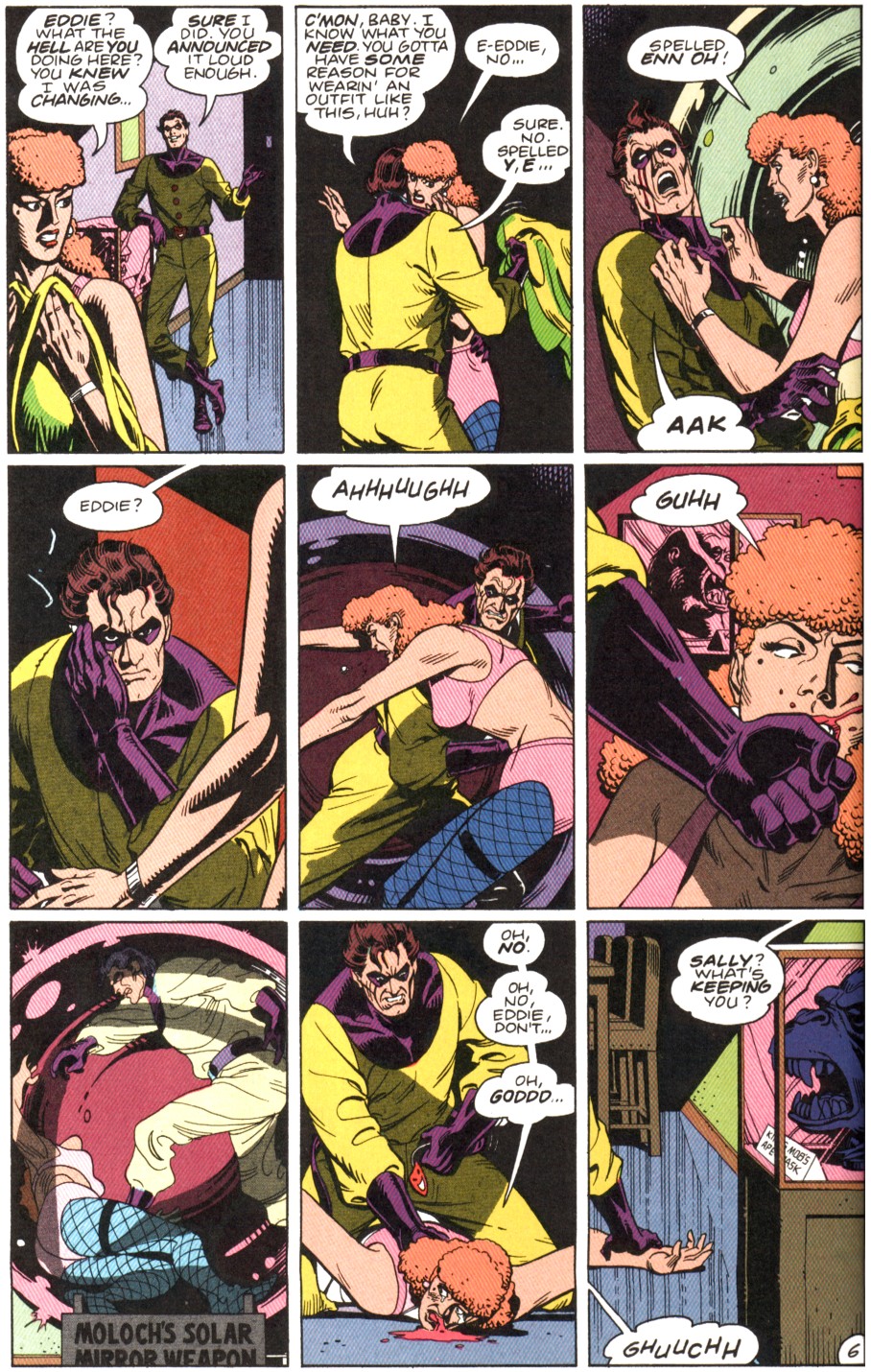

In Cooke’s revisionist take on Laurie’s story, this sensitive, observant, psychologically believable focus on a mother and daughter working through their difficult relationship gives way to a chest-thumping, pedantic valorization of men and fathers. Laurie is given two father figures: Hollis and Eddie. After a melodramatic setup of events which involve Sally’s masquerading as an intruder to ambush her daughter (a superhero-in-training trope more befitting of Kick-Ass than Watchmen) and Laurie freaking out and running off with Greg to San Francisco, Sally is made entirely redundant in Laurie’s life. The focus is then shifted to Laurie’s personal growth outside the shadow of Sally and under the covert surveillance of Hollis and Eddie.

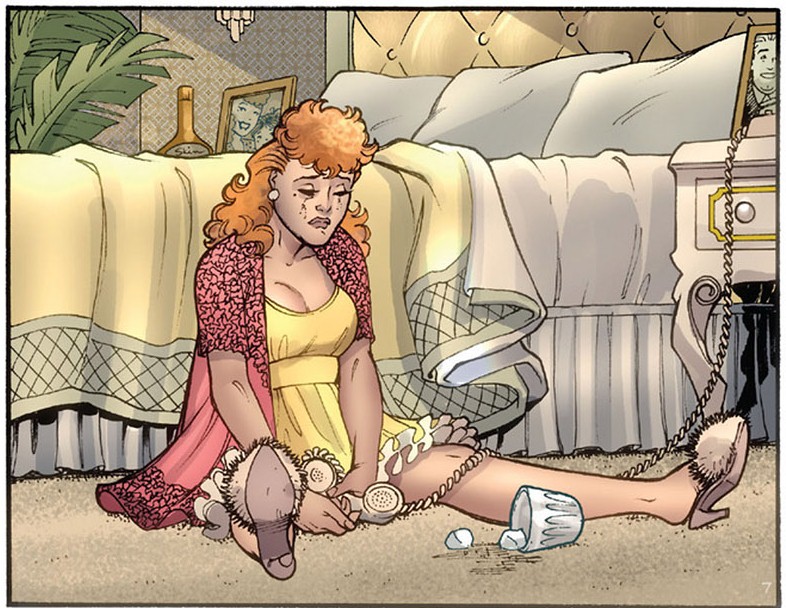

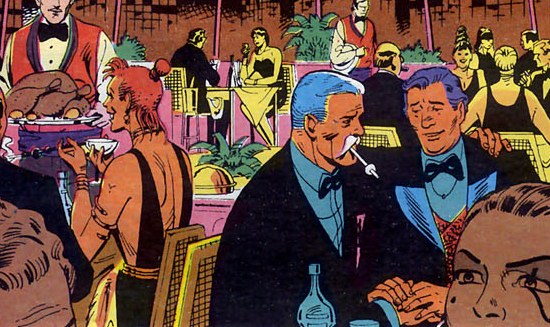

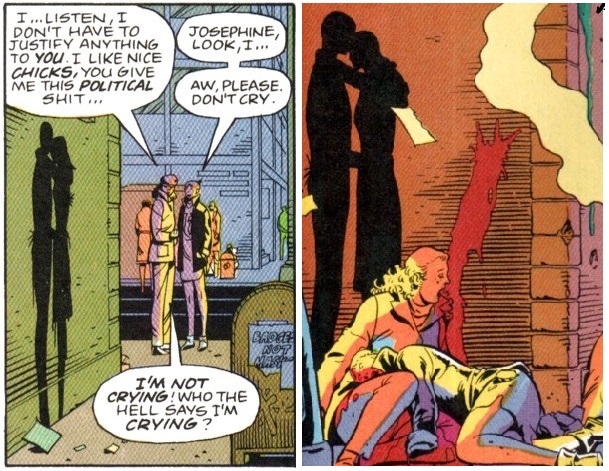

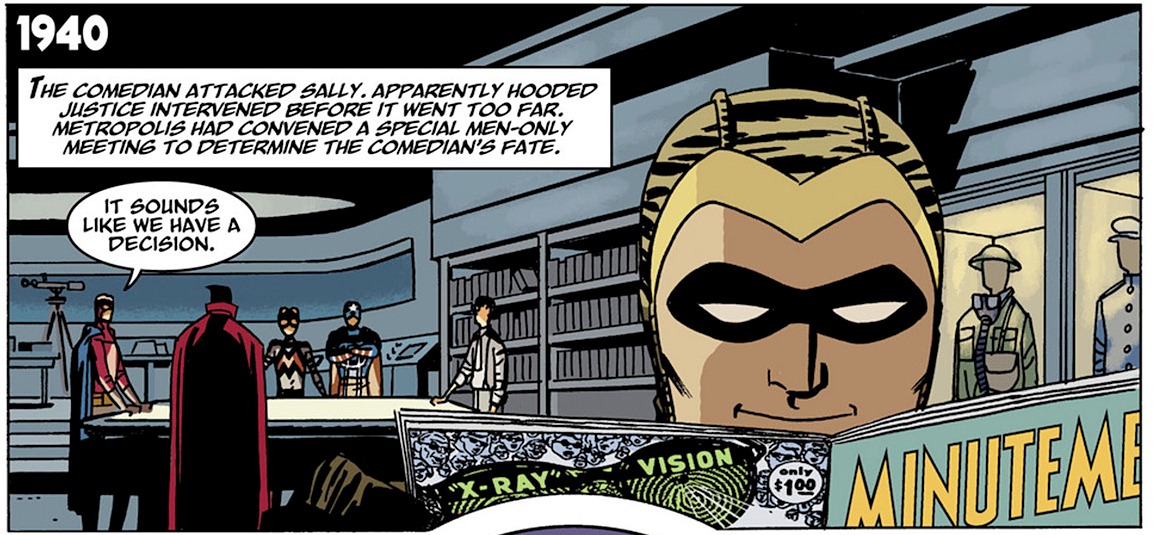

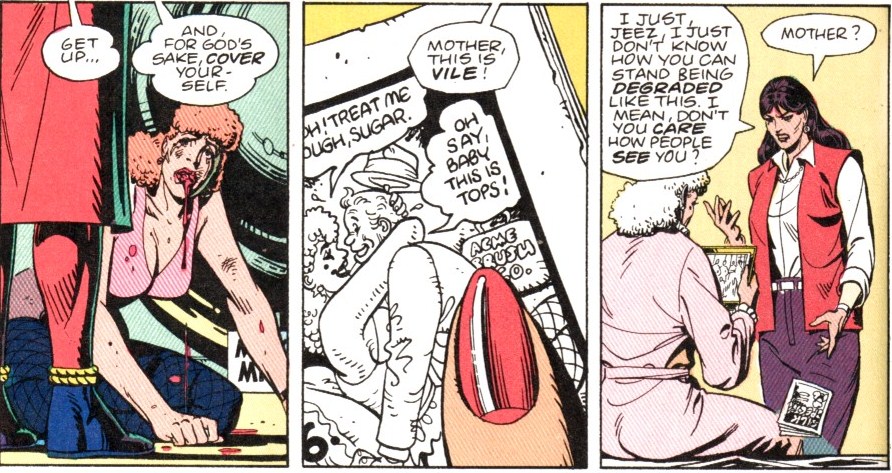

As if making a “dear uncle” out of Hollis isn’t already straining the creative license,[vii] Hollis’ role is expanded by Cooke into practically that of a surrogate father, one who dispenses sage parenting advice to Sally and undertakes to track Laurie down for her. This not only marginalizes Sally but also makes a mockery of her parenting ability, as she alternates between being a sentimental sob, a control freak, a mind poisoner, a basket case and an infantile drunk (Figure C3).

In comic book terms, the devolution of the Wonder Woman fantasy is complete. Marston created an anti-patriarchal fantasy in which women founded a paradise without men. Moore brought this fantasy down to earth by depicting the conflicts and reconciliation between a mother and daughter forced by circumstances to fend for themselves. Cooke reconstructs this reality into a patriarchal fantasy in which chivalric men can make everything okay for neurotic, incompetent women.

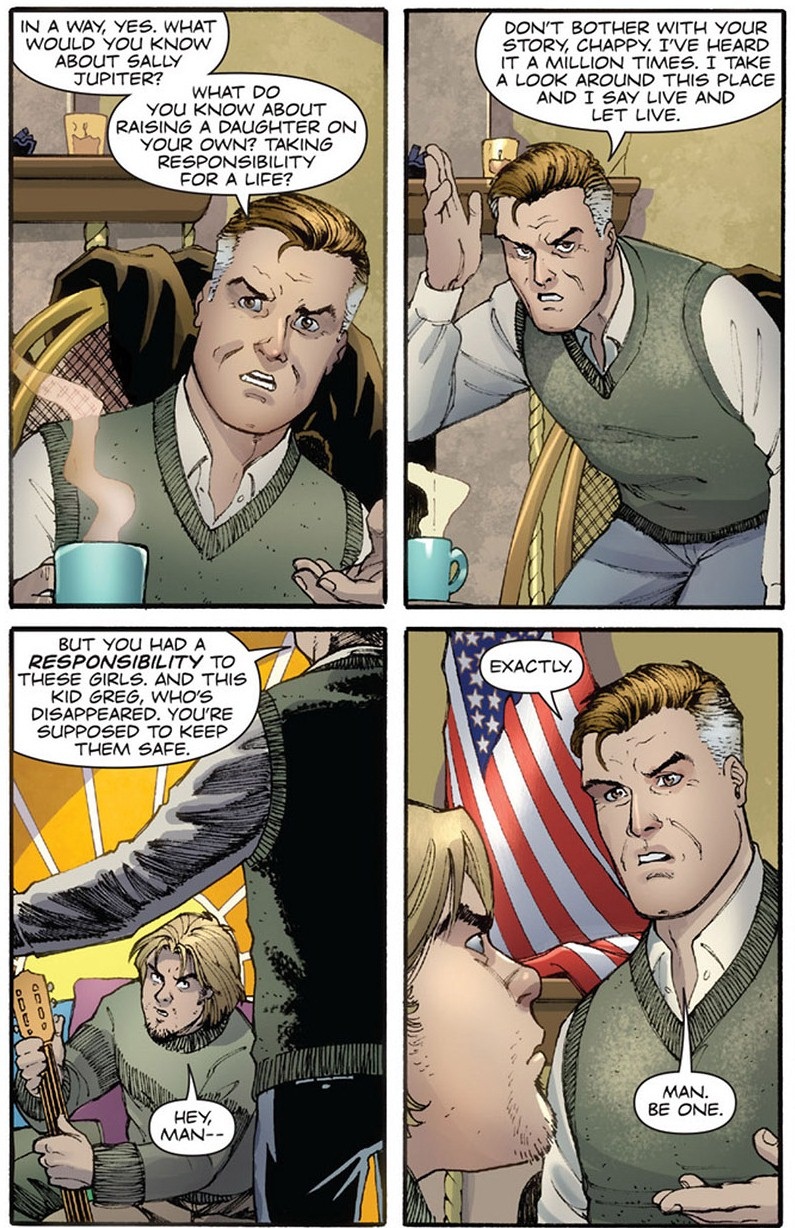

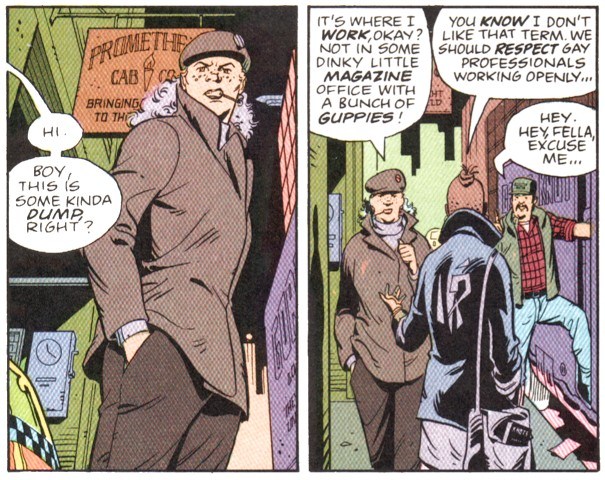

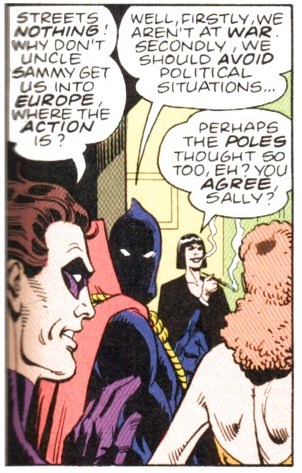

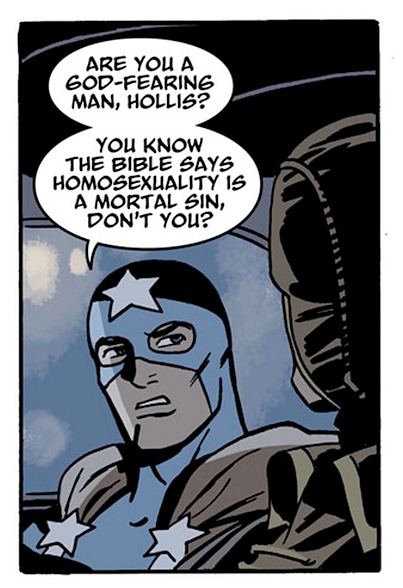

This paternalistic message is forcefully stated in Hollis’ “be a man” speech to Laurie’s hippie friend, Chappy (Figure C4).

It is one of those moments about which it wouldn’t be exaggerating to claim an author is speaking through his character and articulating his “heroic ideal”: namely, the patriotic value of traditional gender roles (note the American flag next to the Mitch Romney-lookalike Hollis in the last panel). Being a man, according to this ideal, is about being chivalric to women, and the plot validates this by presenting a male-affirmative fantasy in which the hardship of women is articulated by a man and the rift between a mother and daughter is healed by the intervention of a man.

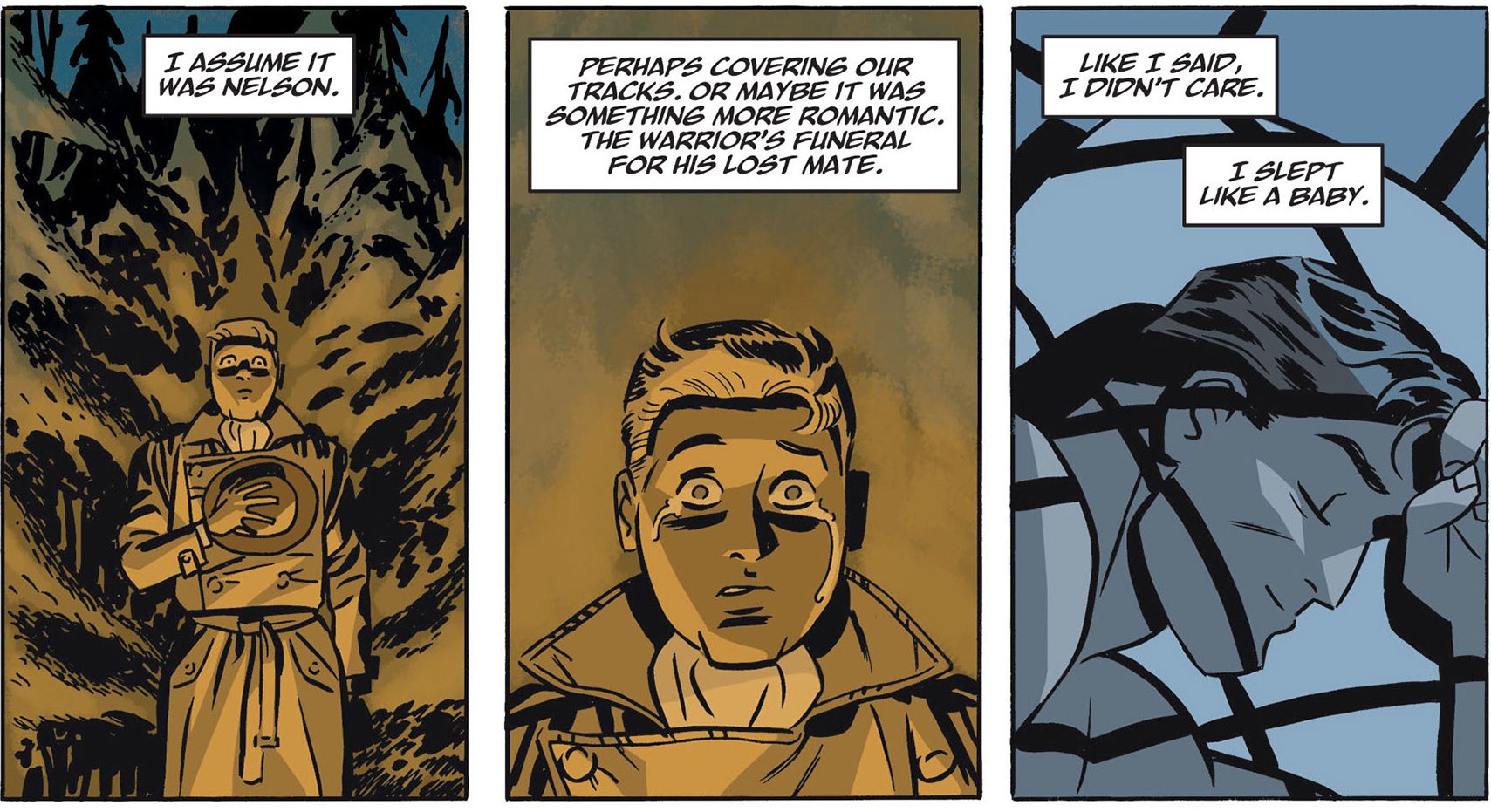

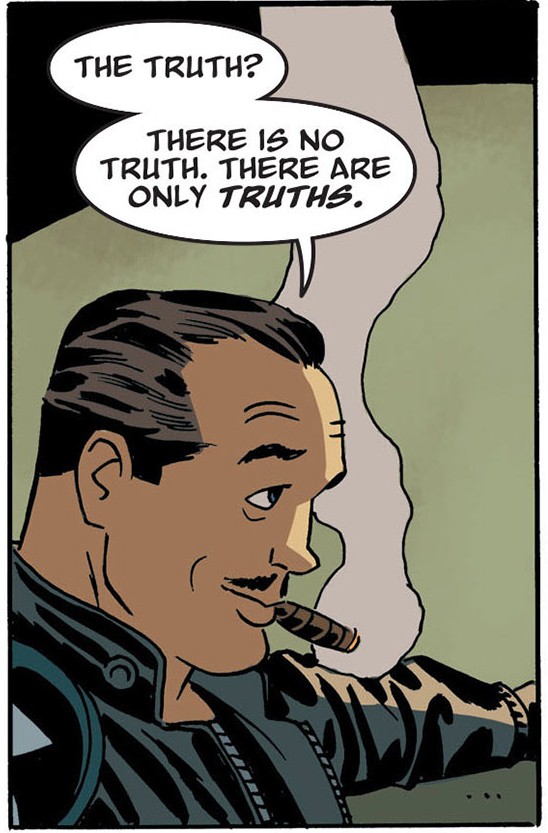

Even more problematic is Cooke’s inclusion of yet another bow-wow cameo for the macho antihero, Eddie. In Moore, Eddie’s failure as a father and human being is one of the book’s cautionary examples of power abuse. The price Eddie has to pay for his addiction to aggressive power-play is the severing of every meaningful human tie, and the bully who has spent his life thrusting the “truth” in people’s faces finds in the end that the joke is on him as he couldn’t even bring himself to own up to his biological daughter.

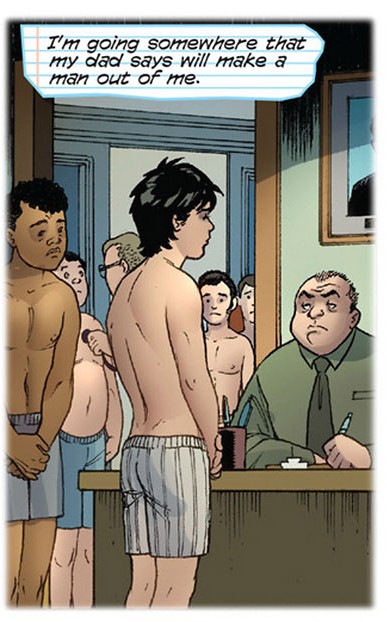

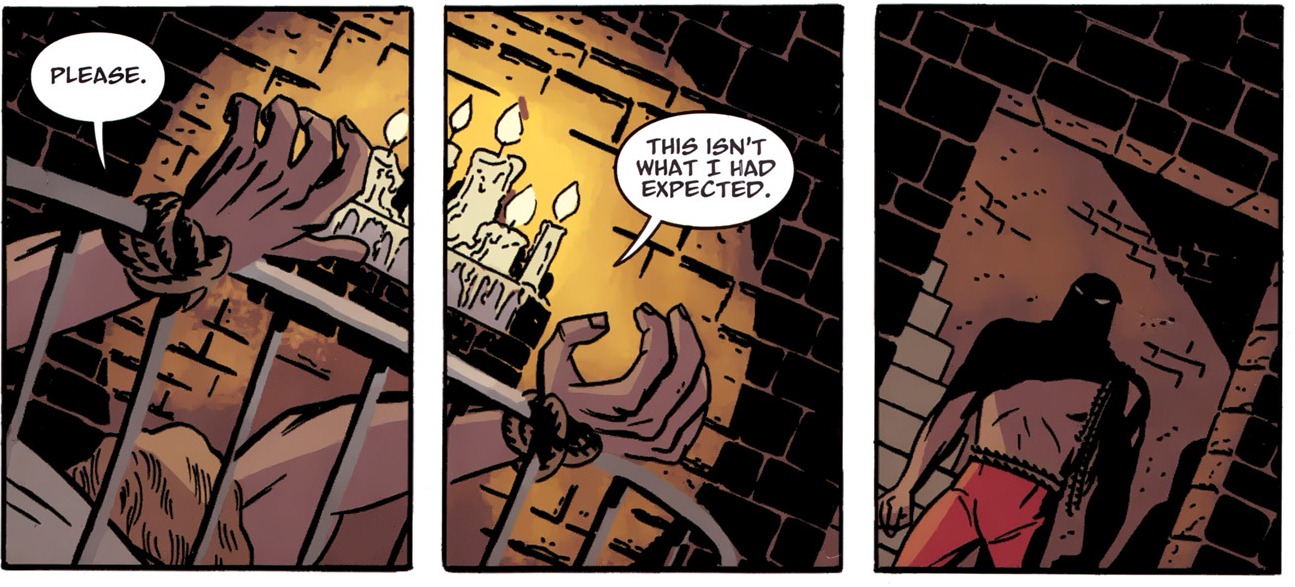

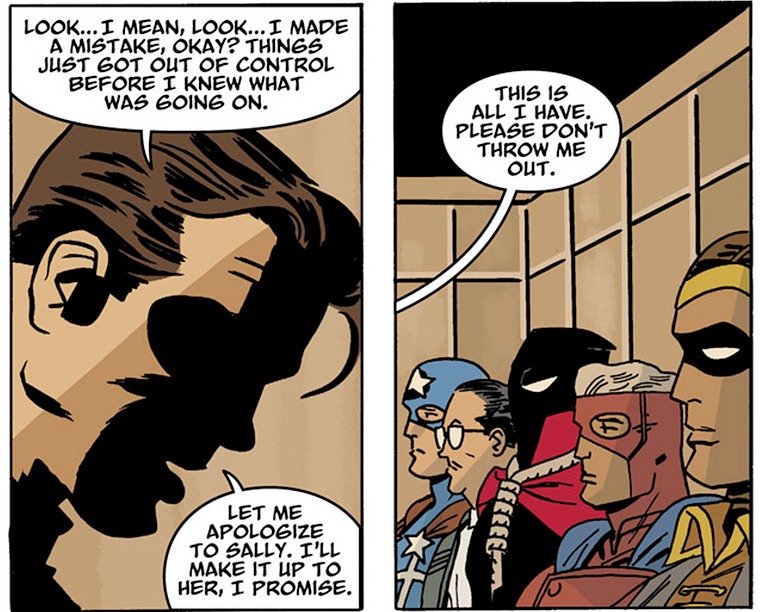

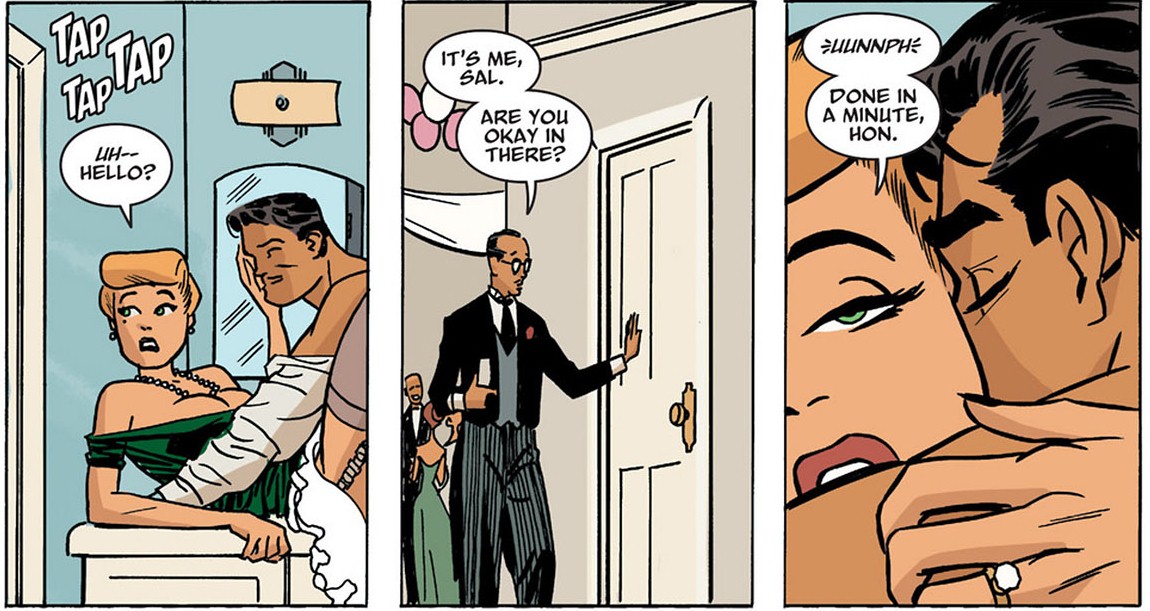

In Cooke, no wrong exists which isn’t rightable when it comes to good old Eddie. Force and aggression only enhance his worth and efficacy as a father. He is the trump card and secret weapon Sally summons in an emergency to sort out Laurie’s problems. Although big daddy may seem rough and tough, he always has a soft spot in his heart for his little princess. Eddie kidnaps Greg and roughs him up for inadvertently supplying Laurie with drugs. However, Cooke is quick to assure us that Eddie is only being cruel to be kind: he forces Greg to break off his relationship with Laurie and sends him to the army to make a man of him (Figure C5).

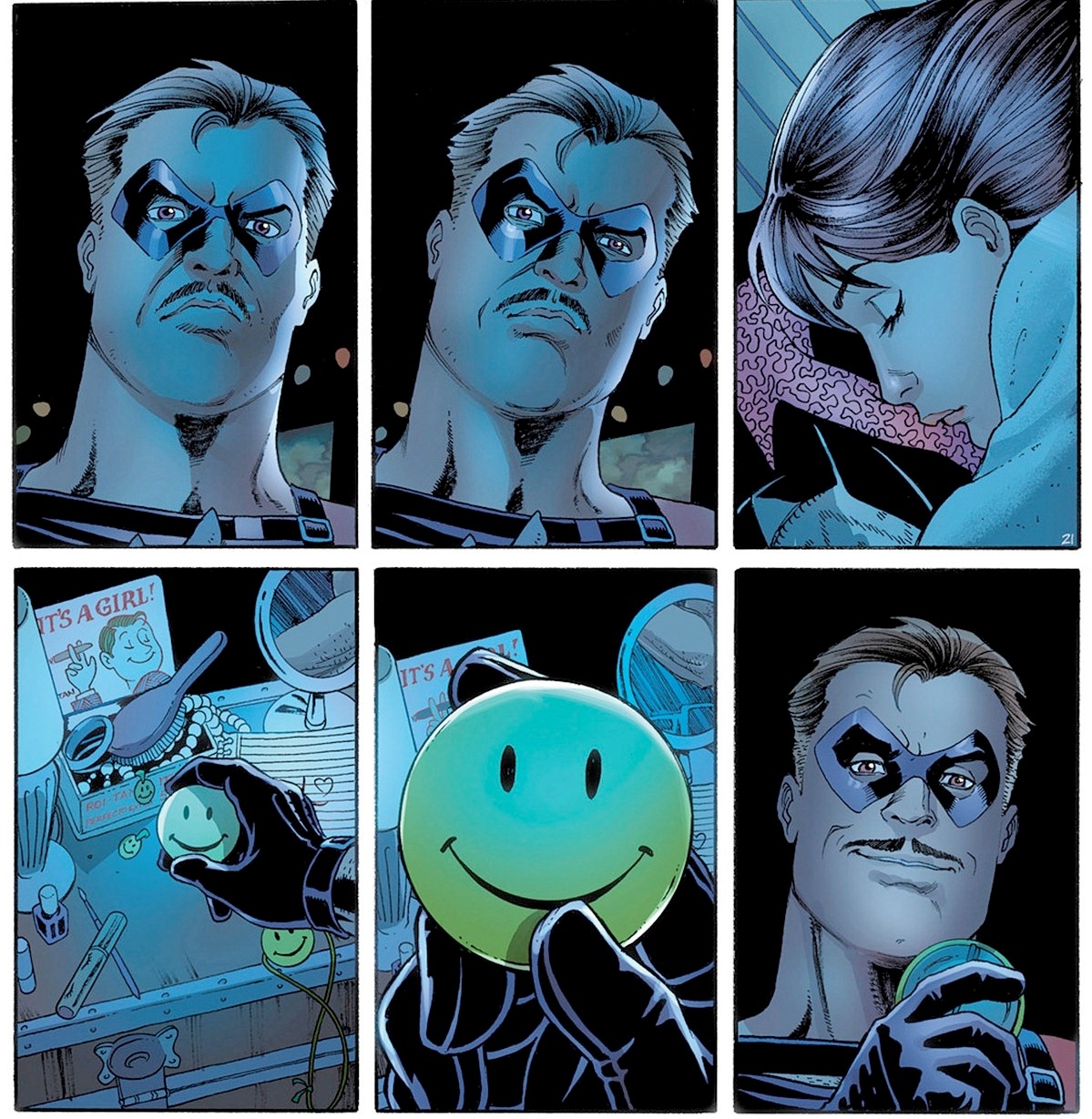

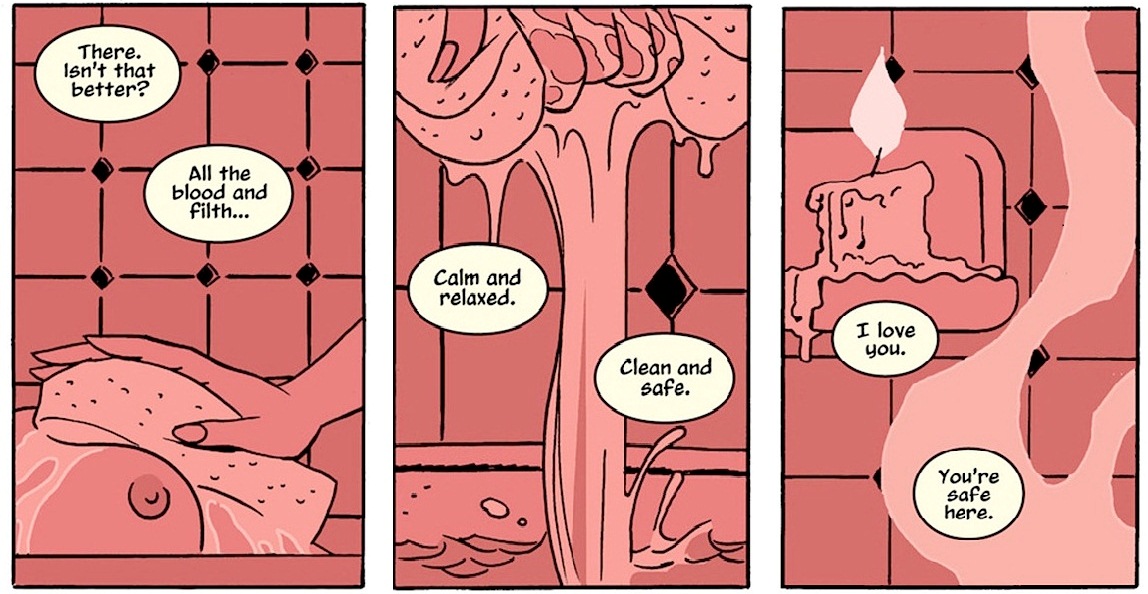

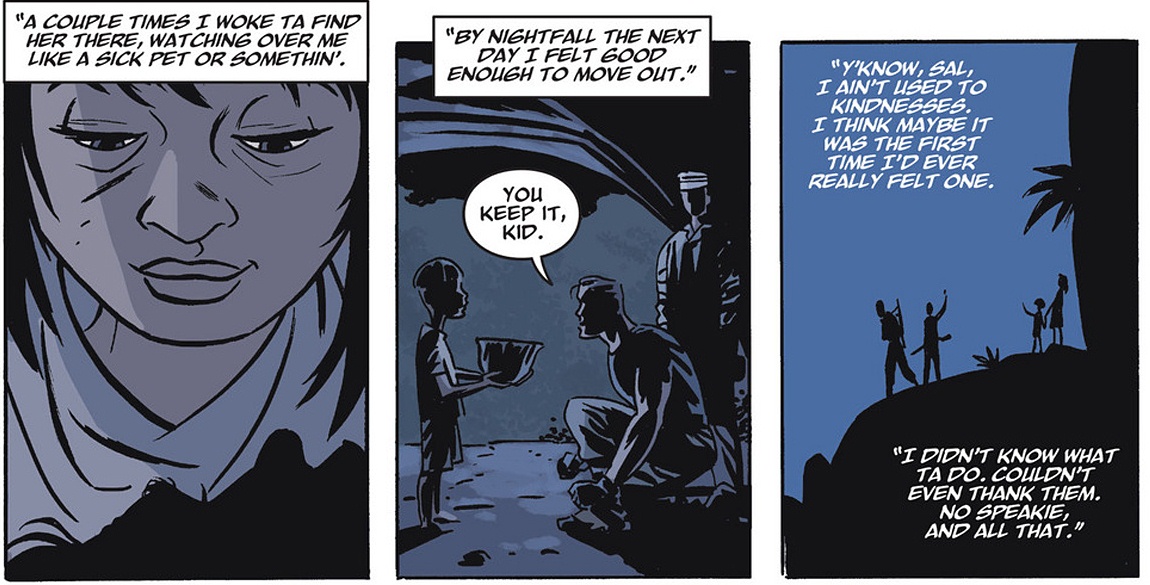

Using “enhanced interrogation techniques” as an effective means to an end, Eddie is no longer a borderline psychopath who enjoys domination and destruction for their own sakes. He is now a Batman-like figure who uses violence and intimidation to achieve the noble purpose of teaching soft-hearted boys to become action-ready, responsible men. And Eddie’s caring, paternal side is fully exhibited when he drops by to visit Laurie in the middle of the night (Figure C6).

He steals into his daughter’s bedroom, coddles her pussy cat, gazes fondly at her sleeping face, and smiles approvingly at her collection of Comedian-inspired accessories untainted by human bean juice. He has become literally her “watchman”.

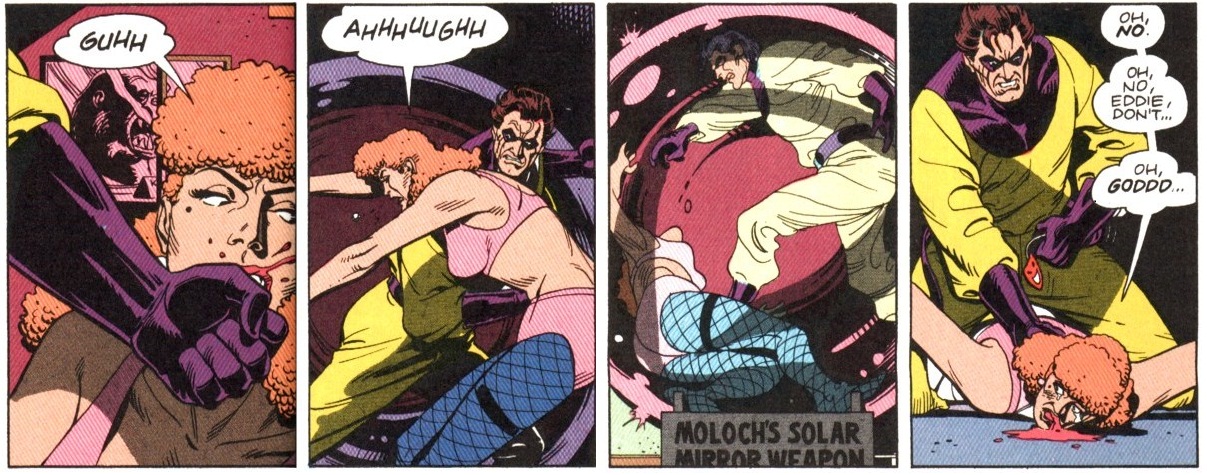

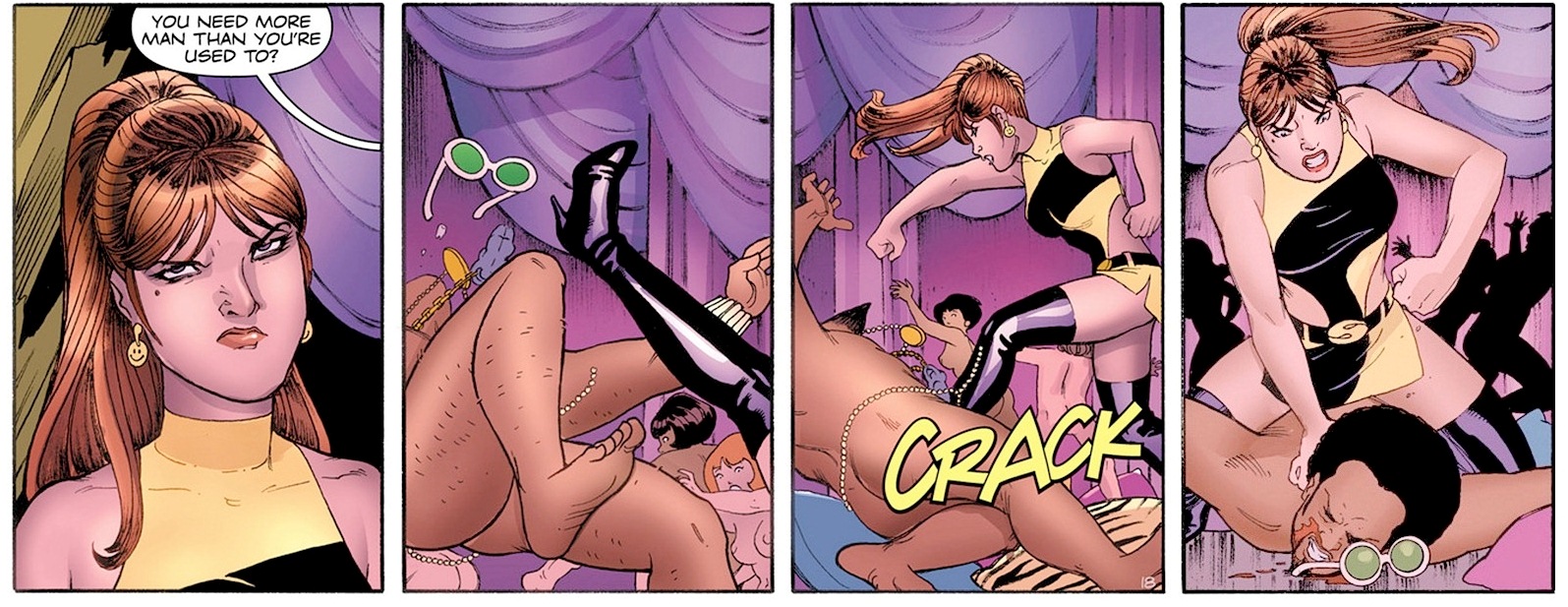

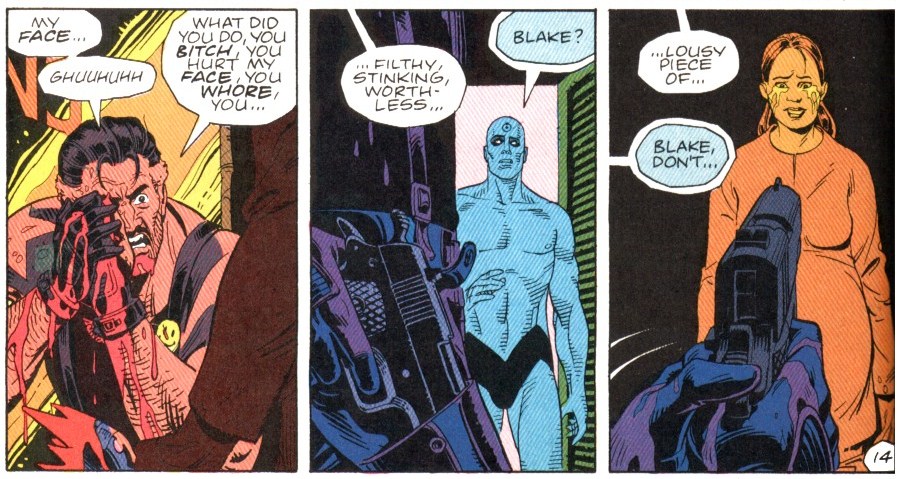

More disturbingly, Cooke’s determination to valorize Eddie’s fatherhood even leads him to re-envision Eddie’s attempted rape of Sally as a positive influence on Laurie. This is demonstrated in Laurie’s first major heroic outing in which she breaks up a drunken orgy, knocks down the seedy drug lord Gurustein, and proudly calls herself “Silk Spectre” to her defeated foes. What is shocking about the sequence isn’t the nudity or pretence of liberal sexuality—compared to the frank, nuanced, mature exploration of sex in Moore’s other writings, Cooke’s and Conner’s try-hard attempt to be daring is almost puerile. The shock comes from Cooke’s and Conner’s gobsmacking decision to depict Laurie’s crowning moment of heroism as a re-enactment of Eddie’s violation of Sally (Figures C7-8).

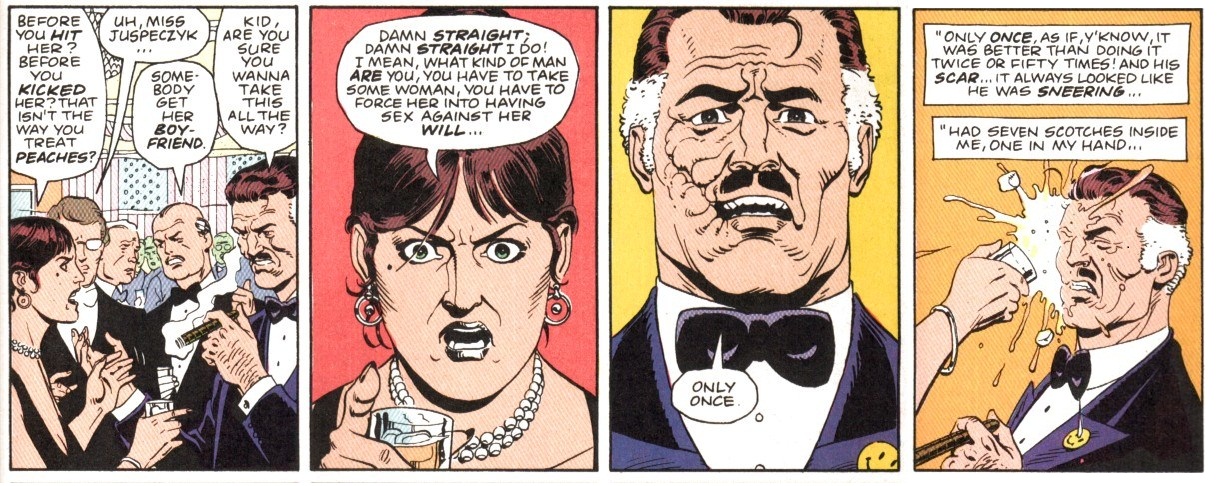

Wearing smiley earrings and a cute pout on her face, Laurie is a badass chick delivering rough justice to a mean black dude. Like father, like daughter. It is blatantly obvious what effect Cooke and Conner are aiming for here. But the question they apparently didn’t have the wits to ask themselves is what on earth led them to think it’s okay to use Moore’s serious critique of misogynistic violence as a vehicle for their shallow indulgence in kick-ass theatrics. Cooke may do all the talking he wants about respecting female characters and Conner may present herself as a champion of her gender in a male-dominated industry (e.g. Zalben, “FanExpo” pars. 4-7); but to take the most well-known rape scene in mainstream comics and turn it into a celebration of the rapist’s progeny bespeaks gross insensitivity and moral blindness, not to mention being deeply offensive to the spirit and intelligence of the original Watchmen. Reading the scene almost made me want to toss a glass of scotch into Cooke’s and Conner’s faces by way of affirming the original Laurie’s rage at the White House cocktail party (Figure C9).

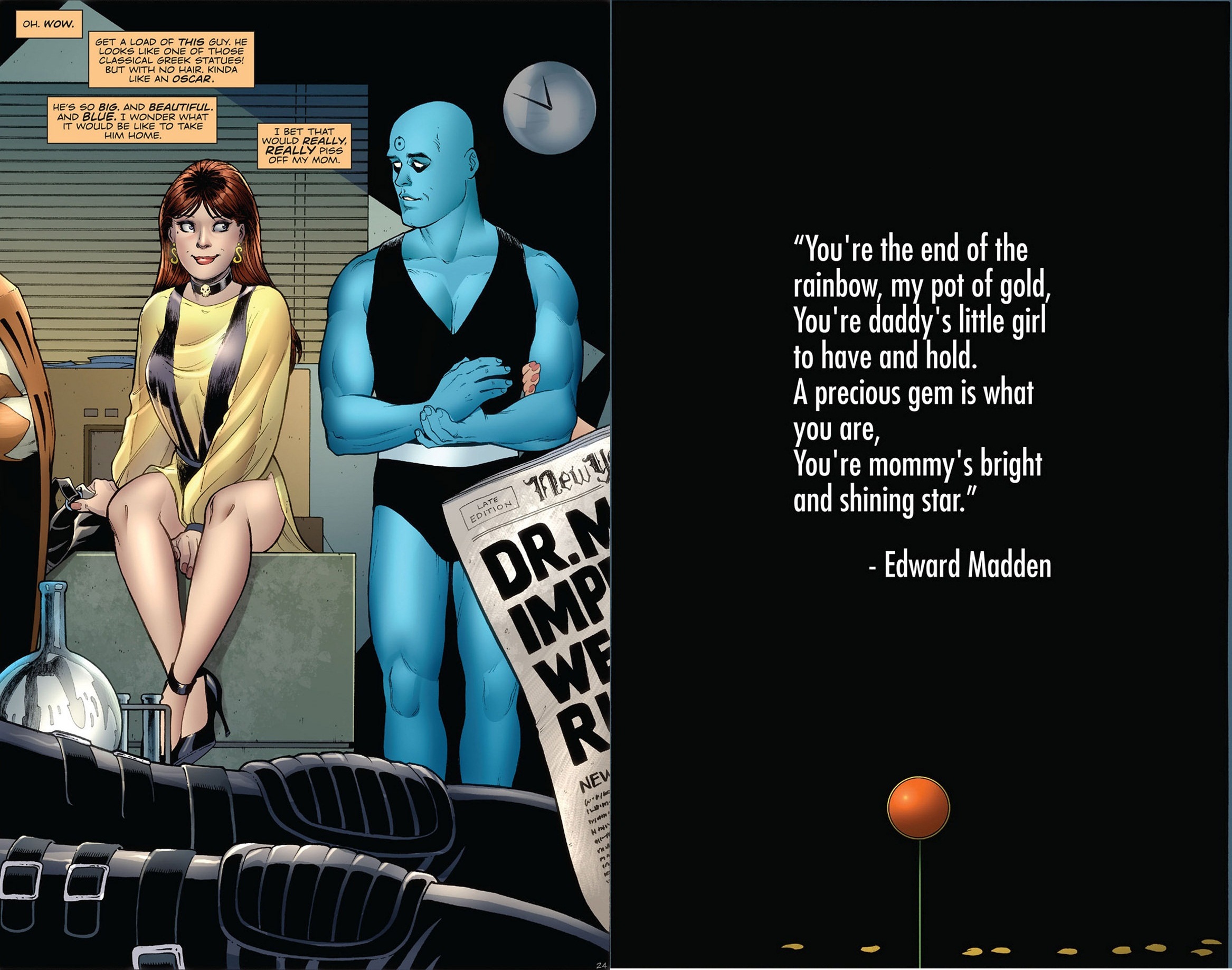

Proving that ignorance is the best excuse, Cooke and Conner see no evil and press on with the rest of the story. Hollis tracks down Laurie; she agrees to go home to mum; tears, hugs and kisses all round, leading to a quick conclusion showing Laurie’s attendance at her first Crimebuster meeting. The story purports to be about a young woman’s search for her freedom and identity, but the tone of condescending paternalism is detectable to the end. In the final image, Cooke and Conner depict Laurie being surrounded by all the important men in her life (Figure C10)—Sally is nowhere to be seen; her influence is reduced to an afterthought.

On Laurie’s left-hand side is Jon, in whom she is interested; on her right-hand side is Dan, with whom she will end up. But the most problematic is once again the presentation of Eddie. True to the original comic’s depiction of the Crimebuster meeting, Eddie is reading a newspaper with his feet propped up on a desk. But going beyond the original, Eddie’s stretched-out legs are visualized in close-up extending across the lower section of the panel, so that Laurie is symbolically sitting on his lap. The corner of his newspaper touches Jon’s crotch, suggesting that daddy is keeping a close eye on the blue man’s interest in his little girl.

In Moore, Sally’s and Laurie’s relationship is the primary focus that saves the story from being mostly about men. In Cooke, Laurie’s relationship with men is reinscribed as a primary focus even in a story that is supposed to be mostly about her.[viii] In an attempt to replicate Moore’s narrative style, Cooke ends the series with an epigrammatic quotation. Yet, possessing neither Moore’s encyclopaedic knowledge of high/pop culture nor discriminating taste for apposite, insightful citation, Cooke settles on a cringe-worthy passage from Edward Madden’s banal pop tune “Daddy’s Little Girl”. The impact of this dumbing-down cannot be overstated. To the provocative philosophical question on which the original Watchmen concludes—“Quis custodiet ipsos custodes. Who watches the watchmen?”—Cooke seems happy to offer a chauvinistic answer: “Daddy is watching; everything is fine”. The exploration of a mother’s and daughter’s relationship and a young woman’s search for her identity is reduced to a cloying male-affirming fantasy about a sexy young chick being watched over by her powerful daddies.

Not Quite an Extraordinary Freelancer

It should be clear from the above that I’m not a fan of Darwyn Cooke. I say this despite knowing that many well-informed people have embraced his Before Watchmen series. I will even concede that he is a highly accomplished visual artist. But any writer who undertakes to revise another writer’s work should expect to be held to the standard of the original. And when almost everything that makes the original incisive and brilliant has been conventionalized and trivialized in the revision, this isn’t a problem that some neat drawings can make up for. Moreover, Cooke hasn’t been slow to criticize other people’s interpretations of Watchmen: he has likened the experience of watching Zack Snyder’s 2009 film to “being bored to death in slow motion” (Zalben “FanExpo” par.13). While I too have reservations about that film, I would point out that at least Snyder didn’t pander to fanboy prejudice by romanticizing lesbians, villainizing gay men, and whitewashing heterosexist violence. At least rape is still condemned as rape, and a subplot about women dealing with the consequences of male aggression isn’t reconstructed into a chauvinistic tale about “daddy knows best”.[ix] I never thought I would say this, but all things being relative, I’ve even started to find Snyder’s take on Watchmen sensitive and nuanced.

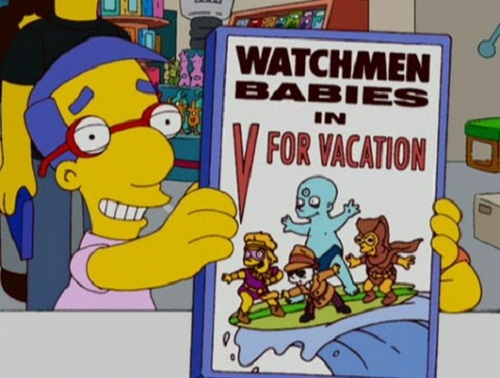

Reading Cooke reminds me of a brilliant Simpsons episode (Season 19, “Husbands and Knives”) featuring Alan Moore in cameo with two other comic book creators he was happy to identify as peers. In the episode, Art Spiegelman, Dan Clowes and Moore appear as animated versions of themselves in a book-signing session at Springfield’s new comic book store. On being approached by Millhouse to sign his “Watchmen Babies” DVD (Figure D1), Moore flies into a mock angry rant about how “those bloody corporations … take your ideas [and] suck them like leeches until they’ve gotten every last drop of the marrow from your bones”.

Yet, when Comic Book Guy later sneaks into the store and tries to sabotage his rival’s business, the three writers activate their League of Extraordinary Freelancers’ superpower, tear off their shirts to reveal their unbelievably ripped torsos (Figure D2), and take turns beating the crap out of Comic Book Guy.

The point of the satire is obvious. Moore, Clowes, Spiegelman—and I would add Harvey Pekar to the list—call themselves “alternative comic book creators” precisely because they aren’t interested in patriarchal fantasies about the “heroic ideal”. Instead of stroking male egos and peddling fanboy clichés, their best works turn the “heroic ideal” on its head and remind us that there are enough pathos, wonders and “thermodynamic miracles” in the lives of ordinary men and women to form the basis of profound, purposeful, original storytelling. They are the visionary deconstructers of the medium, not its reactionary reconstructers.[x] Cooke might think that he is worthy to follow in Moore’s and Gibbons’ footsteps, but on the evidence of his work in Minutemen and Silk Spectre, I suggest that he either: (a) doesn’t truly “get” what Moore and Gibbons were doing, or (b) is so attached to his “heroic ideal” that he has no scruples about hijacking their masterpiece to peddle his own nostalgic heterosexist agenda. If this is the best he can do, perhaps he should consider sticking to The New Frontier-type material in the future. I don’t think it’s safe to leave Watchmen entirely in his hands.

WORKS CITED

Amacker, Kurt. “An Interview with Alan Moore by Kurt Amacker.” Seraphemera Books 13 Mar. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://www.seraphemera.org/seraphemera_books/AlanMoore_Page4.html>.

“Comic Book Roundup: Before Watchmen.” Comic Book Roundup 13 May 2013. 18 May 2013. <http://www.comicbookroundup.com/search_results.php?f_search=before+watchmen&Find= >.

Cooke, Jon B. “Toasting Absent Heroes: Alan Moore Discusses the Charlton-Watchmen Connection.” TwoMorrows Publishing. Aug. 2000. 18 May 2013. <http://twomorrows.com/comicbookartist/articles/09moore.html>.

Callahan, Timothy. “Somebody Has to Save the World: Captain Metropolis and Role-Playing Watchmen.” In Richard Bensam, ed. Minutes to Midnight: Twelve Essays on Watchmen. Edwardsville, Illinois: Sequart Research and Literacy Organization, 2012. Kindle Edition.

Gaines, Dixon T. “Alan Moore Didn’t Just Make Comics an Art Form, He Made Them Gay, Too.” Queerty 4 Mar. 2009. 18 May 2013. <http://www.queerty.com/alan-moore-didnt-just-make-comics-an-art-form-he-made-them-gay-too-20090304/>.

Gifford, James. “Occulted Watchmen: The True Fate of ‘Hooded Justice’ and ‘Captain Metropolis’.” 2003. 18 May 2013. <http://www.nitrosyncretic.com/pdfs/occulted_watchmen_2003.pdf>.

Hughes, Mark. “Alan Moore is Wrong about Before Watchmen.” Forbes 2 Feb. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://www.forbes.com/sites/markhughes/2012/02/01/alan-moore-is-wrong-about-before-watchmen/>.

Keating, Erin M. “The Female Link: Citation and Continuity in Watchmen.” Journal of Popular Culture 45.6 (2012): 1266-1288.

Khoury, George. The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing, 2003.

Klock, Geoff. How to Read Superhero Comics and Why. New York: Continuum, 2002.

Moore, Alan, “Invisible Girls and Phantom Ladies”. The Daredevils #4-#6 (Apr.-Jun.1983), Marvel UK. <http://glycon.livejournal.com/15725.html>.

Pepose, David. “Best Shots Extra Reviews: Before Watchmen: Minutemen, AVX VS”. 29 Aug. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://www.newsarama.com/10092-best-shots-extra-reviews-before-watchmen-minutemen-avx-vs.html>.

Perry, Spencer. “Comics: Before Watchmen: Minutemen Review.” Superhero Hype. 6 Jun. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://www.superherohype.com/features/articles/170975-comics-review-before-watchmen-minutemen-1>.

———. “Comics: Before Watchmen: Silk Spectre Review.” Superhero Hype 13 Jun. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://www.superherohype.com/features/articles/171113-comics-before-watchmen-silk-spectre-review>.

Pindling, Lejorne. “Alan Moore #5 ~ On Super Heroes [Street Law Productions].” YouTube.com 27 Jun. 2008. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=a72aqEwjYOg> [account deleted]

Robinson, Lillian S. Wonder Women. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Sneddon, Laura. “Grant Morrison: Why I’m Stepping away from Superheroes.” New Statesmen 15 Sep. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://www.newstatesman.com/blogs/voices/2012/09/grant-morrison-gay-batman-superheroes-wonder-woman>.

Thomson, Iain. “Deconstructing the Hero.” Comics as Philosophy. Ed. Jeff McLaughlin. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2005. 100-129.

Truitt, Brian. “Before Watchmen: Darwyn Cooke Spends Time with Minutemen.” USA Today 4 Jun. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/life/comics/story/2012-06-04/Before-Watchmen-Minutemen-comic-book-series/55380956/1>.

Yin-Poole, Wesley. “Comics, Games and—of Course—Watchmen: Dave Gibbons Interview.” Eurogamer.net 27 Jul. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2012-07-27-comics-games-and-of-course-watchmen-dave-gibbon-interview>.

Zalben, Alex. “Before Watchmen: Minutemen 1 is the Very Best Modern Comics Have to Offer”. MTV Geek 12 Jun. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://geek-news.mtv.com/2012/06/06/before-watchmen-minutemen-1-review/>.

———. “FanExpo Canada: Darwyn Cooke vs. Amanda Conner … to the Death!” MTV Geek 27 Aug. 2012. 18 May 2013. <http://geek-news.mtv.com/2012/08/27/fanexpo-canada-darwyn-cooke-amanda-conner/>.

[i] As far as I know, the fullest argument against Watchmen’s depiction of women is made by E.M. Keating. My problem with Keating’s reading is that her familiarity with Moore and comic book history is emphatically less assured than her familiarity with postmodernist theory. I suggest a lighter dose of Judith Butler and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and better research into Moore, Trina Robbins and Mark Madrid would have done her argument a world of good.

[ii] Although Moore has never acknowledged this reference—he only mentions Nightshade, Phantom Lady and Black Canary (J. Cooke par. 25)—I think the Wonder Woman analogy is too apposite to be ignored. Diana defies Hippolyta to become a superhero; Sally pressures Laurie into becoming a superhero. Hippolyta is an ageless Amazonian queen on the throne of Paradise Island; Sally is a “bloated, aging whore dying in a Californian rest resort” (I.19) called “Nepenthe Gardens”.

[iii] In Marston, the Amazons were given Paradise Island as their sanctuary after being freed from male slavery by Aphrodite. Athena taught Hippolyta how to mould a child in clay into which Aphrodite breathed life. The necessity of men for the purpose of procreation is completely bypassed. For a feminist reading of Wonder Woman’s origin, see Robinson 27-63.

[iv] Moore explicitly reverses the traditional “active male/passive female” dichotomy with Dan and Laurie: “Dan’s a romantic and Laurie is hardheaded, practical, slightly embittered” (Khoury 114). He also subverts the expectations of a traditional power fantasy in which “the hero gets the girl” by having the girl leave the most powerful man in the world to be with a weaker man. Laurie explains: “I’m edgy in relationships with strong, forceful guys. I mean, with Dan, it isn’t like that. As a lover he’s more sort of receptive; the type you can pour your troubles out to.” (IX.8)

[v] One wonders what Moore, a well-known user and advocate of recreational drugs (“it’s difficult to overestimate the impact of psychedelic drugs on my life and work” (Khoury 19)), make of Cooke’s pious attempt to introduce a morally “correct” anti-drug message in Laurie’s story. Leaving aside the question of morality and focussing solely on artistic merits, it’s still hard to avoid the conclusion that nothing Cooke and Conner have done in Silk Spectre to represent the state of drug-filled hallucination hasn’t been done with ten times the intelligence and originality in Moore’s and J.H. Williams III’s Promethea.

[vi] As Moore wryly observes in “Invisible Girls”: “If I were a female comic character, I think I’d be inclined to dress up warm, wear three pullovers at once and never go anywhere without a pair of scissors.” (16)

[vii] Cooke’s construction of a close uncle-niece relationship between Hollis and Laurie seems at odds with the original Watchmen. After Laurie has walked out on Jon in Book III, she turns to Dan for help because he is the only person she could turn to. When he suggests that they call on Hollis together, she only agrees to walk over there with him and doesn’t indicate any particular closeness to Hollis. After their violent encounter with the knot-tops in the alley, she declines to visit Hollis altogether: “I’ve had enough super-hero stuff for one day” (III.16). Hardly “dear uncle Hollis” stuff.

[viii] A valid question to ask is how prominently do Laurie and Sally feature in the books of the other male characters. The answer should offer a clue as to where the priority of the Before Watchmen series lies.

[ix] It is arguable that the film has even improved the book at this point. By omitting Sally’s kissing of Eddie’s photo and having Sally tell Laurie: “You asked me why I wasn’t mad at him. Because he gave me you,” the emphasis has shifted from the exoneration of Eddie to the reconciliation of the women.

[x] In the same way that Watchmen can be called a “deconstruction” of a superhero comic, Maus can be called a “deconstruction” of a war propaganda comic and Ghost World a “deconstruction” of a sexy teen girl comic. I always find it sad and amusing that in Empire Magazine’s 2008 “The 50 Greatest Comic Book Character” list, Vladek Spiegelman came in at no.13, behind Superman at no.1, Batman at no.2, Judge Dregg at no.7 and Joker at no.8!