40 Years of the Same Damn Story, Pt.1

I call it “Story A.”

I wasn’t very clever that day; tired, maybe a little worn to the nub by reading yet *another* story that felt awfully like all the other stories I had read recently.

Sometimes Story A is a genuine delight to read – other times it’s a chore.

“Story A” is the story, the basic setup that defines a genre. Every genre has a Story A. Suspense stories have psychotic serial killers who stalk and kidnap the investigator (if she is a woman) or the female dearest to the investigator (if he is a man.) Fantasy stories have (or at least had for many years) long journey-quests with teams of ill-suited partners. We all know Story A in our genres.

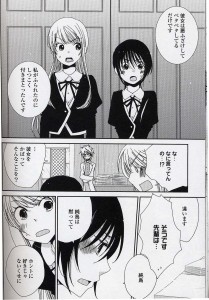

In my chosen area of saturation, Yuri, Story A looks like this:

There is a girl, she likes another girl. The other girl likes her. They like each other. The end.

Sometimes “The end” is signified by a kiss, more often it is signified by holding hands and perhaps looking each other in the eyes. Recognition of mutual affection is as likely to be the final scene as riding off with the Prince to live happily-ever-after is in a fairy tale.

For those of us reading Yuri manga, Story A is the same damn story…and has been for nearly 40 years.

The roots of “Story A” can be traced back at least as far as 1919, with the publication of Yaneura no Nishojo, by Yoshiya Nobuko.

In this book, introverted Akiko meets and falls into passionate, one-sided love with Akitsu. In what was a remarkable ending for its time, the two girls decide to leave school to make a life together, independent of their families or of husbands. In the end, the love was not so one-sided after all, perhaps. (Although some critics have dismissed the idea that they were in love, and instead insisted that Akitsu was leading Akiko into the idea of a politically aware adulthood.) More importantly for our purposes today, this novel has given the manga world any number of tropes that underlie much of “manga for girls” and a whole truckload of Yuri manga tropes, such as life in a Catholic school dorm, intimate piano duet, room in the tower, and others.

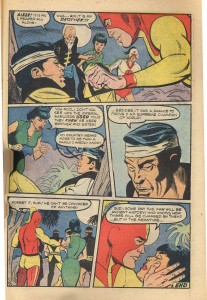

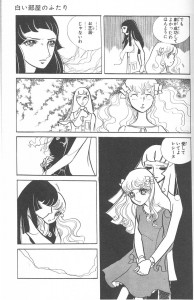

Not quite 40 years ago, a manga appeared on the scene which took these themes and wrapped them in a melodramatic love affair…and “Story A” was born.

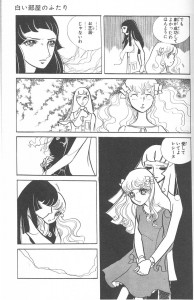

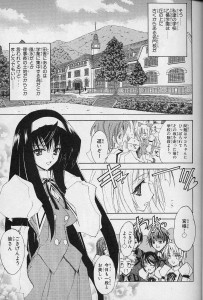

This prototype “Story A,” Shiroi Heya no Futari, also cemented the idea of a tall “Yamato Nadesico,” a traditional Japanese beauty with long black hair, and a shorter, energetic/cheerful girl with blonde or brown hair as the tropiest of Yuri couples.

In the beginning, “Story A” rarely had a happy ending. This is not because of the same-sex love, very few romance manga in the 70’s had happy endings. The typical couple were doomed to never be together for one reason or another. In the case of “Yuri” couples, the options were mostly one partner died or left to get married. In Shiroi Heya no Futari, we get to enjoy one, with a premonition of the other.

The 1980s were not good years for Yuri. The sexual revolution of the 1970s passed, leaving shoujo manga too tired and commercial to take risks. In the 1990s, however, something happened that changed everything…Sailor Moon. I won’t get into how it revitalized manga and anime for girls, but suffice to say that it left a strong impact on many. And it brought same-sex relationships between girls back as a potential manga topic.

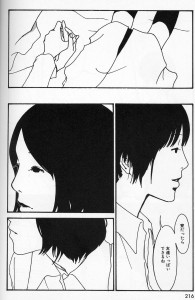

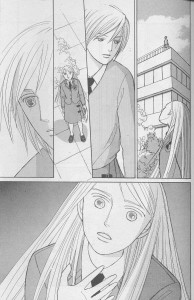

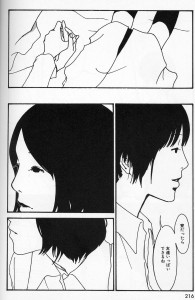

In 1995, Nananan Kiriko drew a very realistic version of “Story A” called Blue, which has been translated into English by Fanfare/ Ponent Mont.

In Blue, we are treated to an alternate version of the “go off to get married” ending, in which Kayako goes “off to Tokyo,” leaving Masami behind.

Blue does not have the Nadesico/cute couple stereotype, but in every other way it fulfills our expectations of “Story A.” If anything, it’s more of a throwback to Yaneura no Nishojo, with a more realistic vision of life in a girls’ school and the resulting drama.

Masami and Kayako meet and find themselves attracted to one another. It’s easy enough to categorize this story as akogare, a Japanese word that means feelings of admiration that are tinged with desire – what we would probably call a schoolgirl crush. Even if one interpreted their feelings as “real,” we can have no real expectation of a “Happily Every After” ending here.

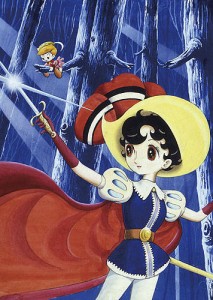

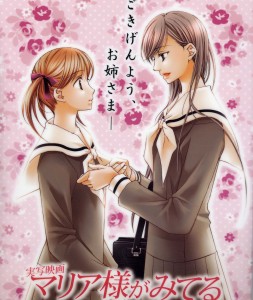

Shiroi Heya no Futari had a profound impact on many series that came out in later years. Not just manga, but Light Novels were also influenced by the Yuri couple trope.

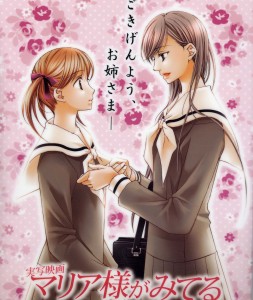

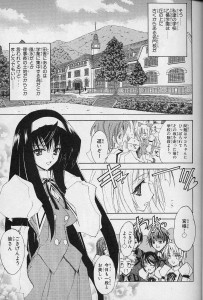

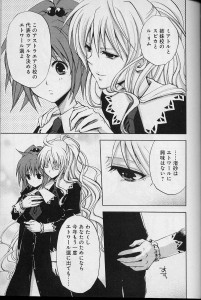

Maria-sama ga Miteru began in 1998 as a serialized “Light Novel” and it continues to this very day. The couple to the right, Yumi and Sachiko, are instantly recognizable to any fan of Yuri and the series, at least at first, is a set of “Story A”s among the students at a private Catholic girls’ school.

Most of these relationships are platonic romance, but within the initial few volumes at least one story went beyond the confines of “Story A,” to tell what can only be seen as a “lesbian” narrative. However popular that story, Ibara no Mori, was, the bulk of the relationships in Maria-sama ga Miteru sit well within the confines of “Story A.” As much as we might wish for it, Noriko and Shimako, Yumi and Sachiko, Rei and Yoshino, will never go running off to make a life together, outside the confines of family or husbands.

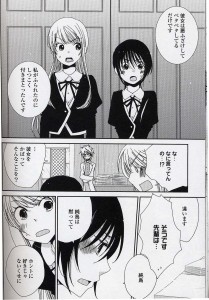

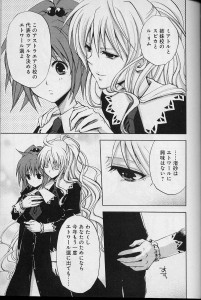

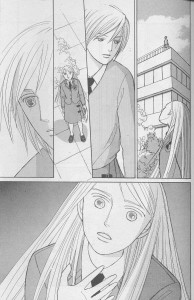

The meme of “love between girls in private girls’ schools” which was initially set by Yaneura no Nishojo, really gained traction in the late 90’s with the success of Maria-sama ga Miteru and, for the next dozen years, it has been a main component of our definitive genre story. “Story A” was to take place in a girl’s private school. Exhibit 4376, this page from Pieta from 2000.

The school was not “St. Whoever’s”, but the hothouse atmosphere of an all-girl school is still the setting, allowing Rio (boyishly attired here in sweater and tie,) to be a school playgirl, while “good girl” Sahako is close to the traditional Nadesico type.

Pieta also contained a common trope for its time – that of linking lesbian romance with mental illness. Rio has a history of hysteria and suicide attempts…all of which have a perfectly excellent explanations and have almost nothing to do with her romance with Sahoko. If anything, their feelings for one another are what redeem Rio and pull her back from the brink of insanity. Nonetheless, it was very fashionable for manga of the time period to have unstable lesbian characters.

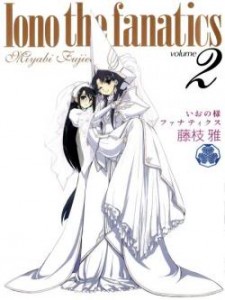

When male manga artists started to pick up what had mostly been a meme in girls’ manga, a distinct “checklist” of tropes became a common feature of “Story A.” Absurdly luxurious private school? Check. Nadesico-type with wealth, power, athletic and scholastic prowess? Check. Genki blonde who is poor, but sincere and inexplicably the object of desire for everyone in the series? Check. Breast-highlighting tight uniforms? Check. In the mid-2000s, Kannazuki no Miko created a whole new wave of Yuri fans, with an action riff on the couple from Shiroi Heya no Futari. Instead of 70s melodrama and partying, we were given giant robots and apocalyptic prophecies.

At the same time Kannazuki was recreating “Story A,” another series that was playing with the same key elements fooled a whole generation into thinking it was telling an original story, by stealing from *every* Yuri story that had gone before it. Strawberry Panic! added a new twist to “Story A,” – a pretend glimpse past the gauze boudoir curtains of an all-girls, no-guys-allowed world. This concept quickly became a typical feature of Yuri “Story A”s aimed at men. (Presumably to heighten the sensation of forbidden love they enjoyed in Yuri.) This added thrill has retroactively invaded popular girl’s series, such as Maria-sama ga Miteru. The radio and live shows – the audience of which are mostly men – now begin with a warning that boys are not allowed. And many Yuri anthologies that target a male audience provide that same warning on the cover, just so the audience knows it’s getting a glimpse of some forbidden women’s mystery.

Where Strawberry Panic! really excelled was as an homage to “Story A” through the ages.

The manga riffed on series like Card Captor Sakura, Himitsu no Kaidan and Maria-sama ga Miteru, while the anime stole openly from Kannazuki no Miko, the above series and even Western stories such as The Graduate and Wuthering Heights. (Amusingly, it wasn’t even the first Yuri anime to borrow from Wuthering Heights. That honor would probably have to go to Cream Lemon: Escalation.)

Take a moment to compare this page with the page from Shiroi Heya no Futari. Do not think that this was accidental.

Take a moment to compare this page with the page from Shiroi Heya no Futari. Do not think that this was accidental.

By 2005, the Yuri ball was rolling well. Not coincidentally, in 2005 I held a Yuricon event in Tokyo, and was able to be there at the formation of a new Yuri-focused magazine, Comic Yuri Hime. Now manga was being created explicitly for readers of “Yuri” as opposed to being one fetish in a series for men, or a schoolgirl crush in a story for girls. But, “Story A” was safe space, where no political, social or emotional commitments had to be made, which made it an attractive “space” in which to create a Yuri story.

The emotions might be real, the attraction may or may not be physical, but the implicit understanding of “Story A,” is that this is not forever – it is for now. As long as we are in school, as long as we are protected from the pressures of our duty to family, friends, jobs, society, we can be together.

What Yuri Hime could do – and has, in recent years done – is give us something that, like Akiko and Akitsu in Yaneura no Nishojo, escape the confines of societal pressure, to create a more realistic “Happily Ever After.”

However, many of the initial Yuri manga that ran in Yuri Hime fell solidly under the auspices of “Story A.” Some hit all the buttons. Hatsukoi Shimai managed to cover exactly “Story A” territory and not too much more. Compare Haruna and Chika here to Sachiko and Yumi in Maria-sama ga Miteru.

Private girls’ school? Check. Nadesico beauty who is smart? Check. Cute energetic girl who is sincere, but not smart? Check? Impossible to understand feelings? Stupid plot complications that keep us apart for no real reason – including, but not limited to interfering seductive person; poor communications issues, and; horrible secret? Check.

In the late 2000s, Yuri took a major jump from elements in various stories to distinct category of its own. Comic Yuri Hime had split into two magazines, each targeting a specific gender audience with some distinct elements, and other manga magazines began running more Yuri-themed manga, many of which continued to follow previously established “Story A” tropes.

In 2007’s Sasamekikoto, the Nadesico beauty Sumika retains her superiority not by wealth and status (as did Sachiko or Chikane,) but by being an accomplished student and good at sports.

The cheerful, energetic girl, Ushio, now is also the doofus-y, somewhat clueless girl, a quality that we see back in Shiroi Heya no Futari with Resine’s lack of awareness of Simone’s feelings – even after they have been explicitly expressed.

Sasamekikoto is on-going, and thankfully for readers everywhere, Ushio has moved away from cluelessness, as the story itself has shifted out of exploration of Yuri tropes and wallowing in “Story A”-ness to having actual lesbian awareness and identity. (I sometimes define “Yuri” as lesbian content without lesbian identity.) By making the characters aware of the impact of their relationship on the people around them – and how it might affect their future – this story has ceased to be purely “Story A.”

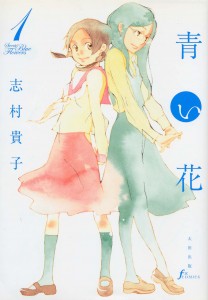

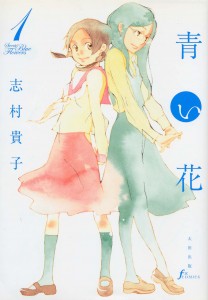

Aoi Hana was another mid-2000’s series that has now become an iconic series for Yuri fans, in part due to stellar writing and characterization and in part due to a not financially successful, but very beautifully made anime in 2009.

Aoi Hana was another mid-2000’s series that has now become an iconic series for Yuri fans, in part due to stellar writing and characterization and in part due to a not financially successful, but very beautifully made anime in 2009.

As you can see, even in color, Fumi fits the Nadesico type, this time with the added attraction of “shy glasses girl,” and Akira is the by now quite-stereotypical energetic, cheerful pig-tailed girl. Don’t let the fact that it appears to be a typical “Story A” fool you – this is a top-notch manga. It is “Story A.” It just happens to be a best of breed.

Like Sasamekikoto, Aoi Hana has some recognition of what it might mean to “be lesbian” and how one’s decisions about one’s self can impact the other people in a life. And, while there are more stories being written now with this awareness, Aoi Hana also shows Fumi coming out, which is still extremely rare in “Yuri” manga.

Story A doesn’t always look exactly the same. In many cases, it looks different…it just feels the same. The characters’ heights may change, their hair color and length may change. Their backgrounds, their previous relationships, their feelings about having these feelings at all. The private school might have a legend of two girls that ran off or attempted suicide together. There may be a tapestry or stained glass under which whispered vows become lifelong committments.

But in the end, there is a girl, she likes another girl. The other girl likes her. They like each other. The end.

And, even though nearly four decades has passed since Shiroi Heya no Futari began, sometimes it just feels like we’re reading the same damn story over and over again.

Sometimes. Every once in a while. We’re not.

But mostly, we are.

Aoi Hana was another mid-2000’s series that has now become an iconic series for Yuri fans, in part due to stellar writing and characterization and in part due to a not financially successful, but very beautifully made anime in 2009.

Aoi Hana was another mid-2000’s series that has now become an iconic series for Yuri fans, in part due to stellar writing and characterization and in part due to a not financially successful, but very beautifully made anime in 2009.