This review originally appeared in the Comics Journal.

When I was thirteen I spent a week with my grandparents at their house in New Jersey. At the time I was interested in Japanese console role-playing games, and increasingly frustrated with how few games actually made it into English translation. In fact, I told my mild-mannered Catholic grandfather, a man who loved radios and computers and science fiction novels, I was thinking about learning Japanese. “Japanese, huh,” he said quietly, looking away from me. “Only one word I ever learned in Japanese.” He paused. “That was “surrender.””

It is doubtful that 89-year-old cartoonist Shigeru Mizuki will ever forget his war time experiences, either. At the age of 20 he was drafted into the Japanese army and stationed at Rabaul, on New Britain in Papua New Guinea, where he survived several near-collisions with death. His friends were not so fortunate. Possibly his most significant personal loss, though, is one immediately apparent from photographs of the man himself—the loss of his left arm.

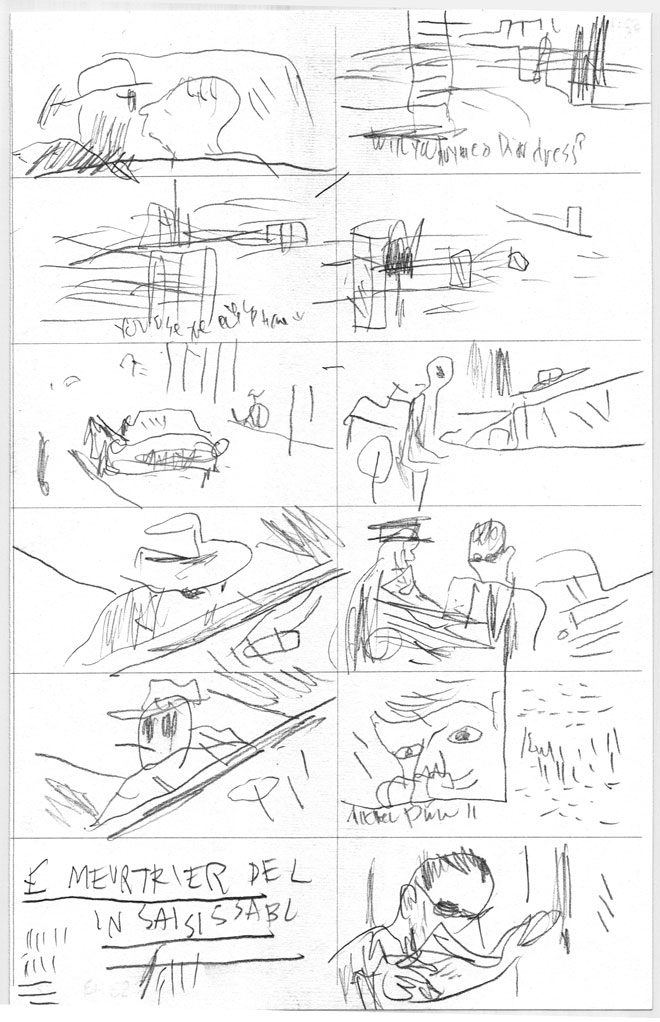

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths (Soin Gyokusai Seyo!) first appeared in 1973, and was inspired by Mizuki’s unintentional reunion with his commanding officer, which led him back to Rabaul after a 26-year absence. It is, according to Mizuki’s afterword, a book of “90 percent fact.” And for that reason, as well as its many strengths and virtues, it is a very difficult book to criticize.

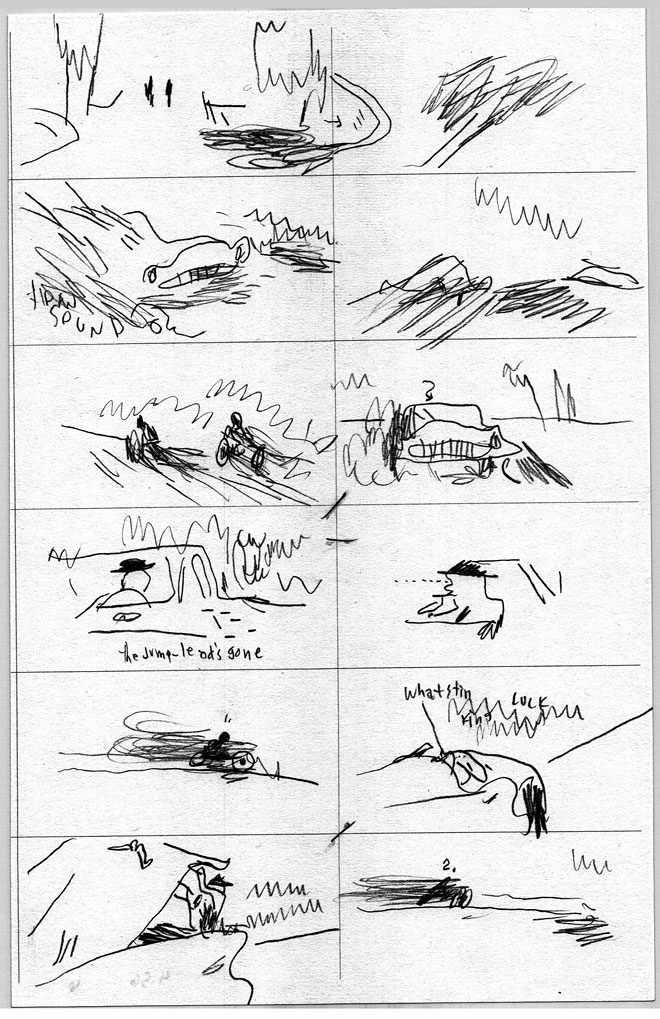

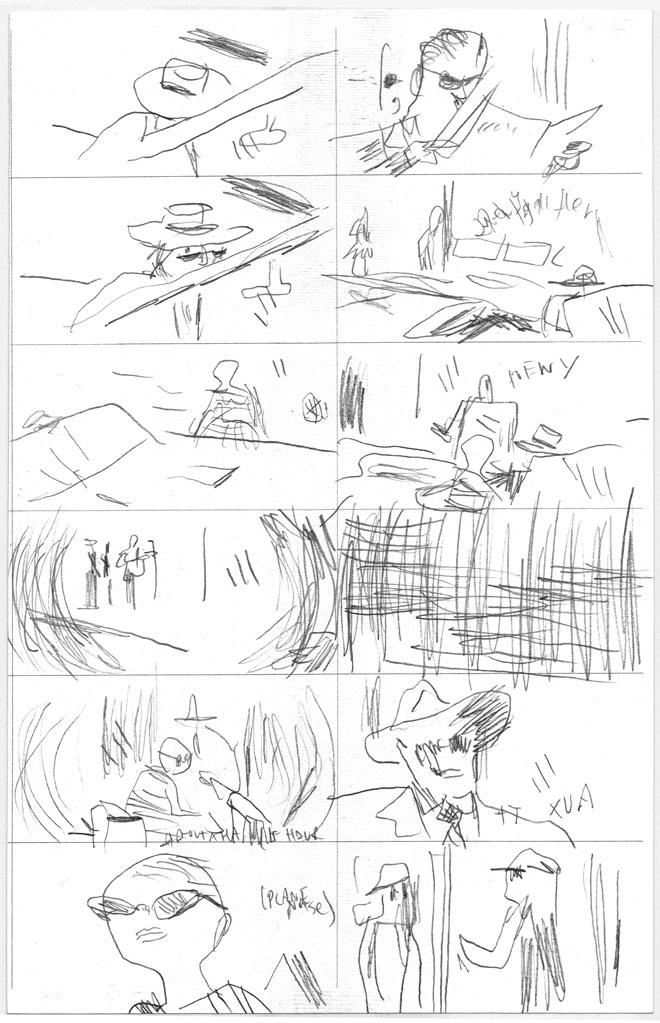

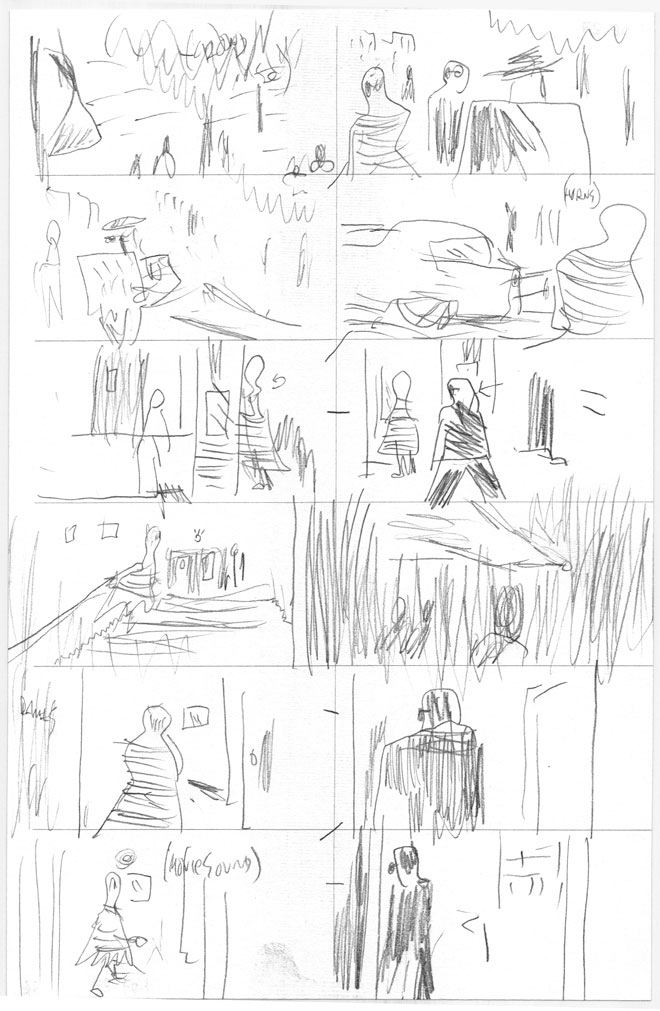

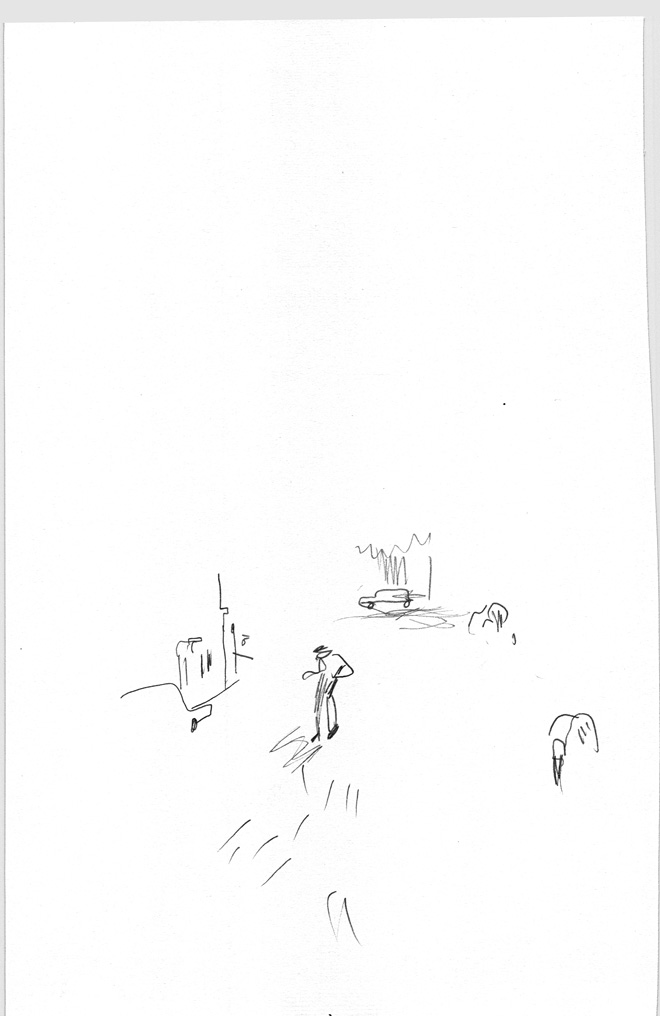

OTOND is an on-the-ground perspective on the inanity and ultimate inhumanity of war, told from the viewpoint of a detachment of soldiers who occupy a portion of New Britain. The soldiers themselves are differentiated mainly by their facial shapes and the unique ways they deal with their hunger and their misery. They pick their noses, build encampments, run fruitless errands for their superior officers who berate and beat them. They dream about women and food, and attempt to satisfy both cravings through talk and pursuit of the latter, including hunting fish with grenades.

The inevitability of death hangs over everything, not just for the reader, but the soldiers as well. As Mizuki said in an interview with the Japan Times, “You feel death already when you receive the call-up papers.” In OTOND, which smartly confines its scope solely to the island on which the soldiers are stationed, the suggestion of the tenuous nature of the lives of these characters comes immediately. Their history- and honor-obsessed (and very green) commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Tadokoro, leads them to claim a bit of new territory south of their current position. When they arrive, bayonets affixed and rifles ready, to find no resistance at all, no people other than themselves, their commander bellows, “WE HAVE TAKEN THIS PLACE WITHOUT BLOODSHED!” “We took this place, he says,” one soldier says to another. “It is almost like heaven, just like you said,” says another as the sun goes down, men silhouetted among the lush palms. And overlapping that sunset, one of the sole instances of narration in the book: “Actually, we were not that far from paradise…”

“Not that far from paradise…”

“Not that far from paradise…”

But death doesn’t need a machine gun and an American flag—death is all around these men. The first to go is crushed by a tree he was carrying, killed in his weakened condition by dengue fever, no doubt made worse by his exhaustion and malnutrition. Another is felled, with no witnesses, by an alligator, another, horrifically, by a fish that he has in his hunger stuffed greedily into his mouth.

And then the enemy arrives.

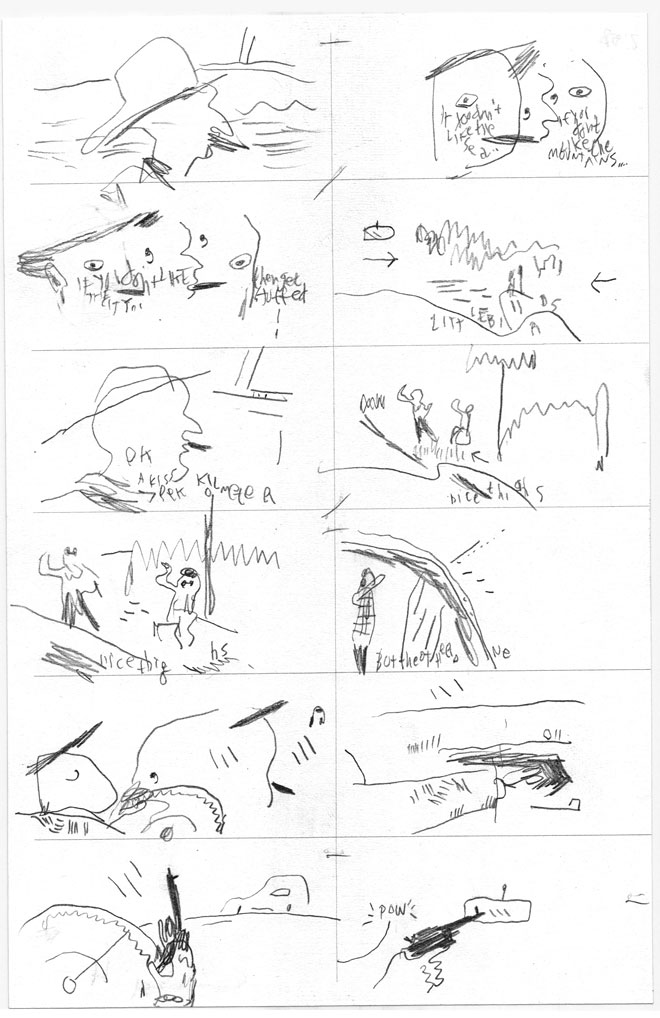

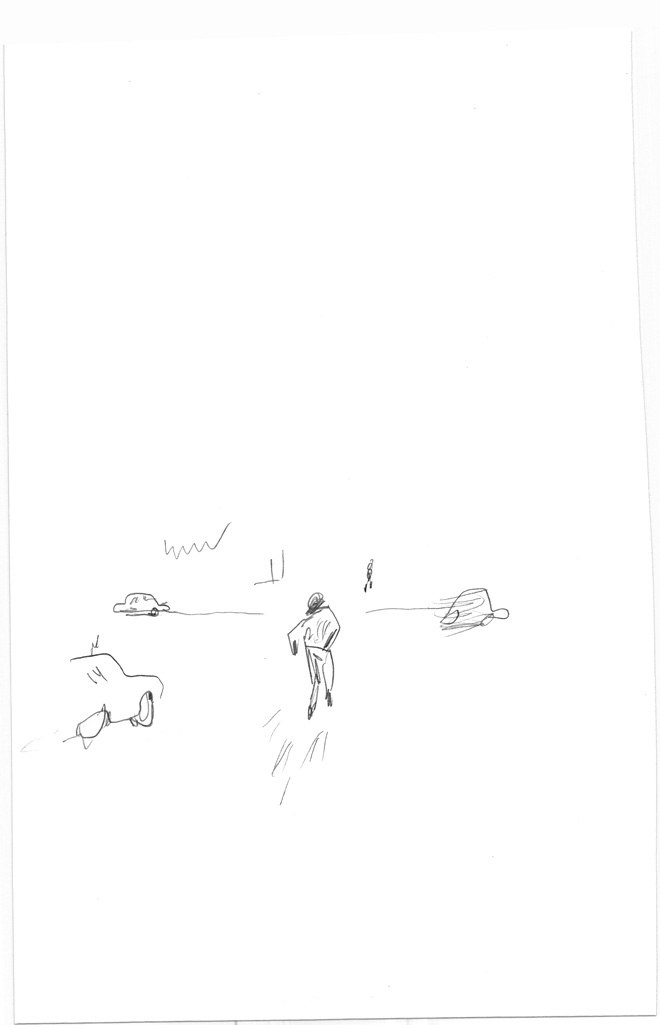

The early fighting is scatter-shot, furtive, small pockets of men shooting at great distances and then retreating, picking off a few here, a few there. The first truly significant encounter with the enemy is not face-to-face, but with their superior foodstuffs—after driving off a presumably small contingent of American soldiers (presumably, because we as reader haven’t seen them at all at this point), the soldiers find a hut full of provisions, including canned goods and chocolate. “Those bastards are living like kings fighting this war,” says one of the soldiers. “Now that I’ve eaten all of this food I can die a happy man,” says another.

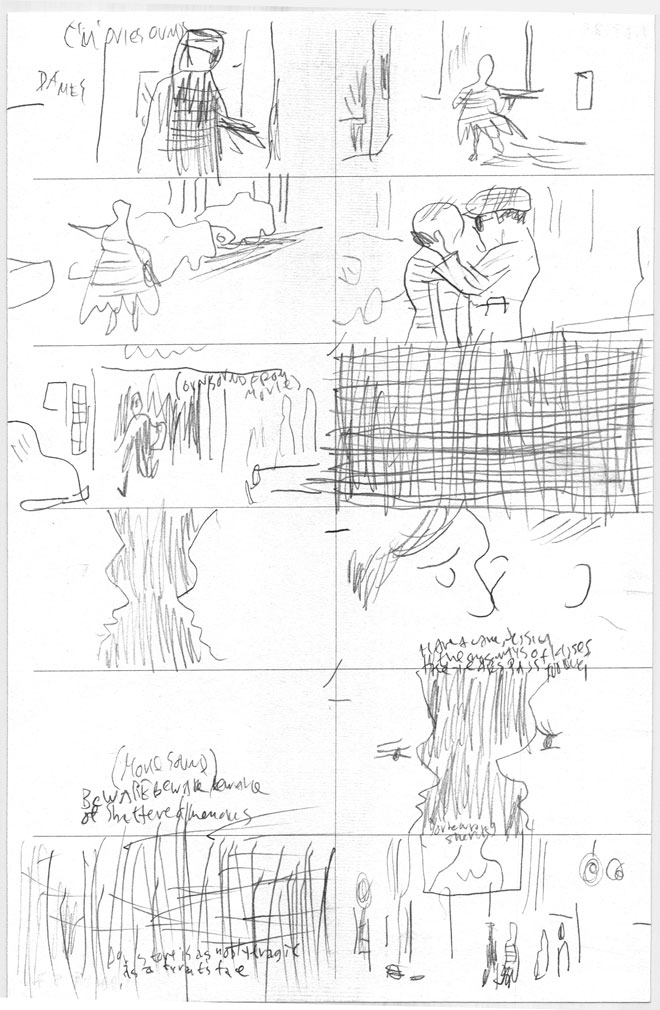

When the fighting finally comes, it comes in bursts of violent punctuation, at a distance, the violence gruesome, inevitable and also somehow impersonal. “Maybe during the Russo-Japanese War you had a chance to ‘see’ the enemy forces,” Mizuki told the Japan Times, “but in the Pacific War, the moment you met the enemy you knew whether you were dead or alive. It was that fast.”

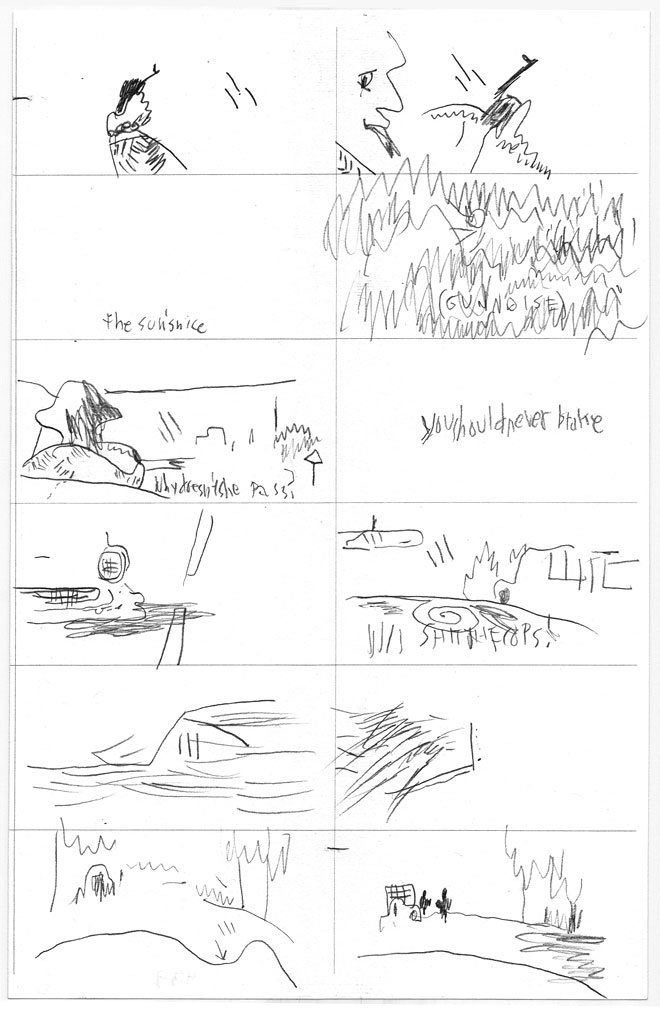

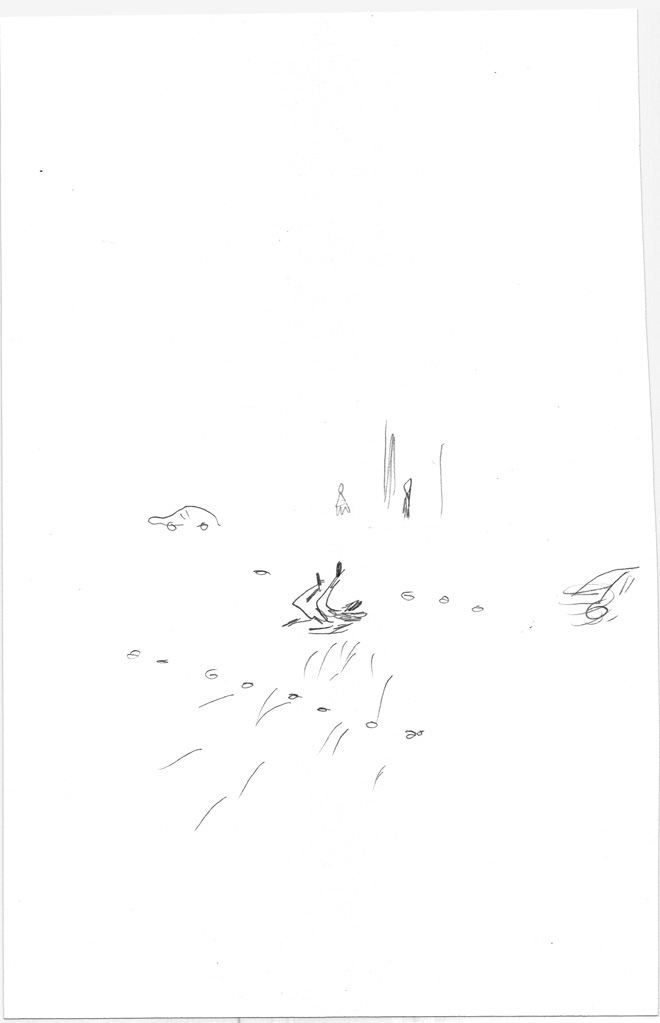

The conflict escalates. Engaging a force superior in numbers and equipment, the specter of annihilation that has so far hovered over the soldiers finally descends. Against the recommendations of his advisers, who plea for strategic retreat, Lieutenant-Colonel Tadokoro orders his men in a suicide charge against the enemy. The men spend their last nights drinking and singing. In the morning Tadokoro instructs his men to turn “towards our beloved homeland and bow in farewell.” “To the RIGHT!” he bellows to the bewildered men. “RIGHT!” They bow, affix their bayonets, and plunge headlong into the enemy.

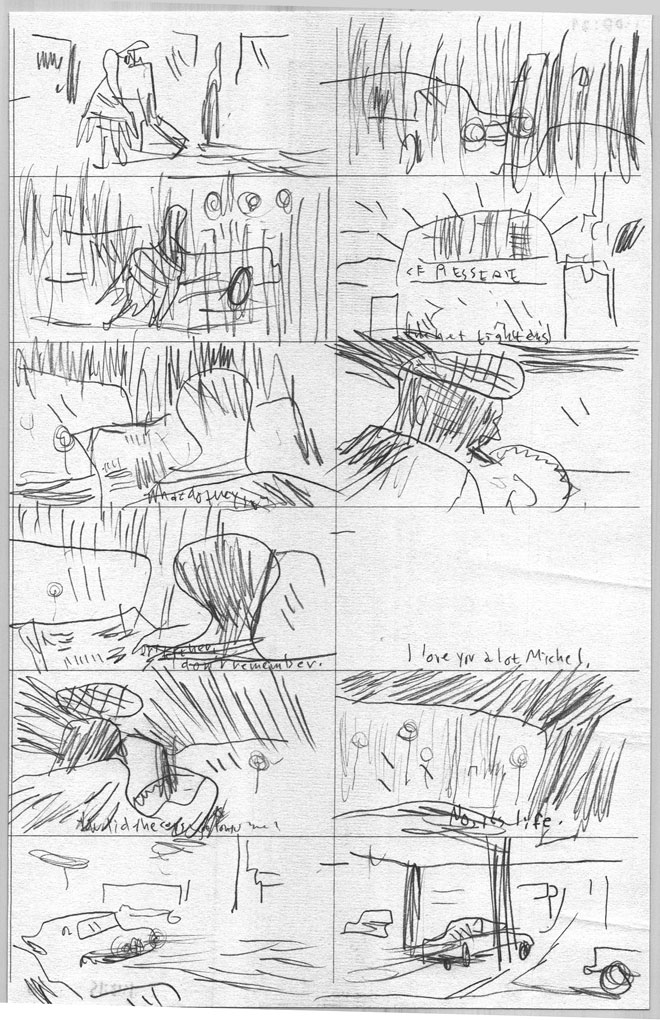

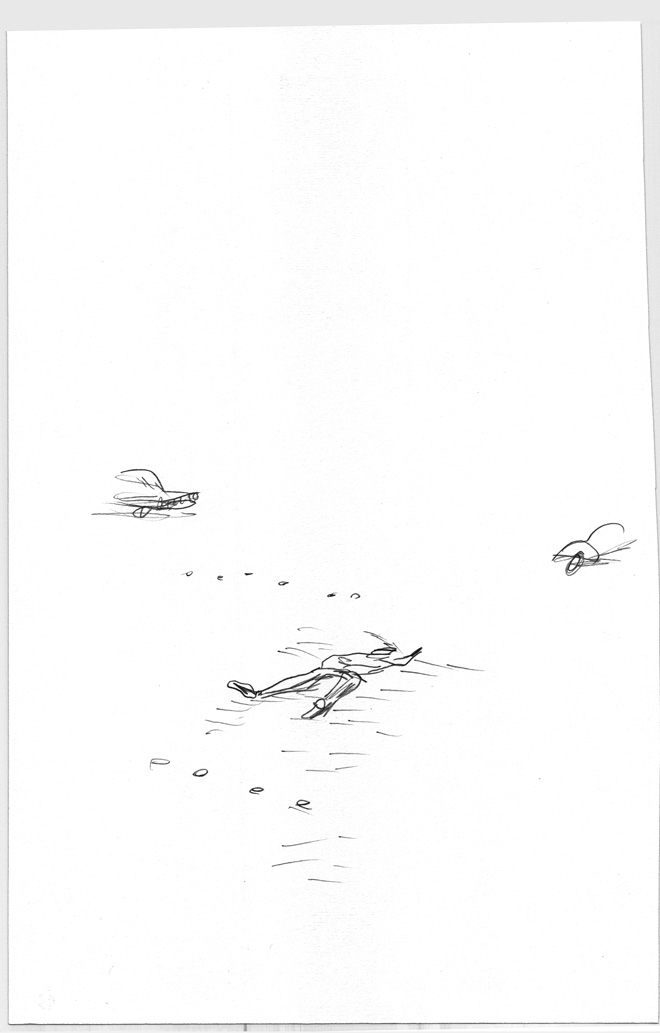

But not all men are so eager to die as their commander, and some survive the horrific battle. The survivors make their way back to their division base, only to find that their deaths have already been reported to headquarters. The only possible reaction to their cowardice in surviving, they are told, is another charge. Coerced from a new arrival from division HQ, beaten down and demoralized, the eighty-odd remaining men raise their voices to sing and charge the enemy in one last pointless push. The last to die is Maruyama, who earlier we have seen illustrating playing cards for his commanding officers, offering to draw their portraits when they all return home. Now his face is grotesquely distorted, maggots in the fresh hole in his face, a song still on his swollen, bleeding lips. He stands, laughing, among the dead, facing an American tank. His abdomen bursts from artillery fire, and he falls, facing us in closeup. He is the last to die, this artist’s surrogate, the sole character with any interiority, whose thoughts we hear at the moment of death.

His body joins the bodies of his friends, now all texture and value, rendered how one might draw a mass of palm tree logs, felled and scattered. As our view gets closer, the piles of bodies turn to stacks of bone, and, finally, crushed remnants, barely recognizable save a few stray bits; a femur, a portion of a skull.

The decision to stage the book solely on the island neatly side-steps details and potential arguments about cause for the conflict and instead forces the reader to address the situation from the situation of these conscripts—men without hope, trapped in a absurd, grotesque situation in which they have few choices, no individual agency to act.

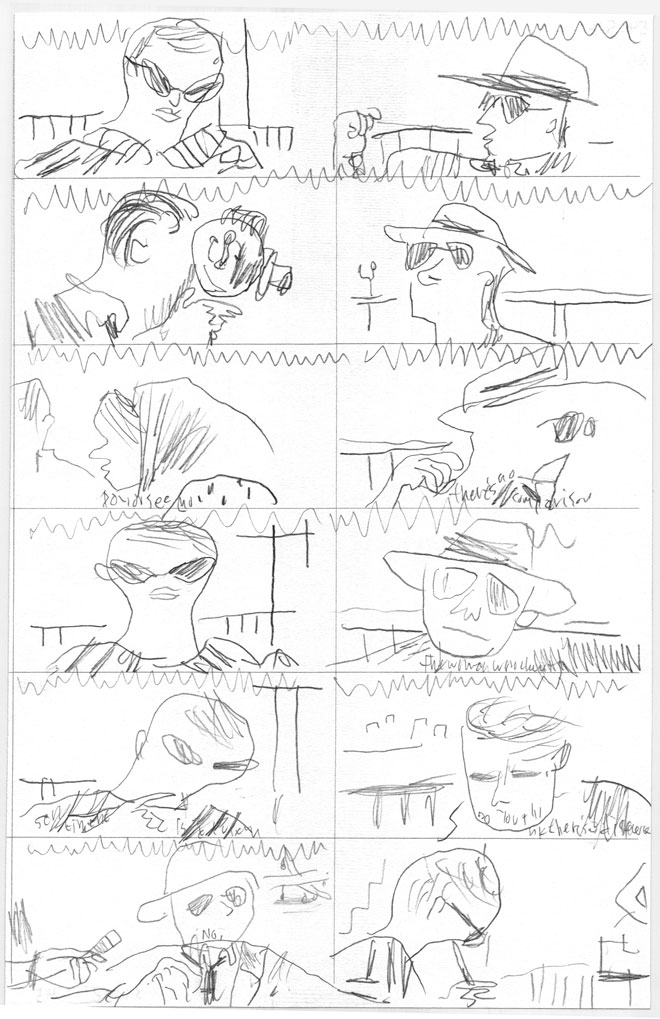

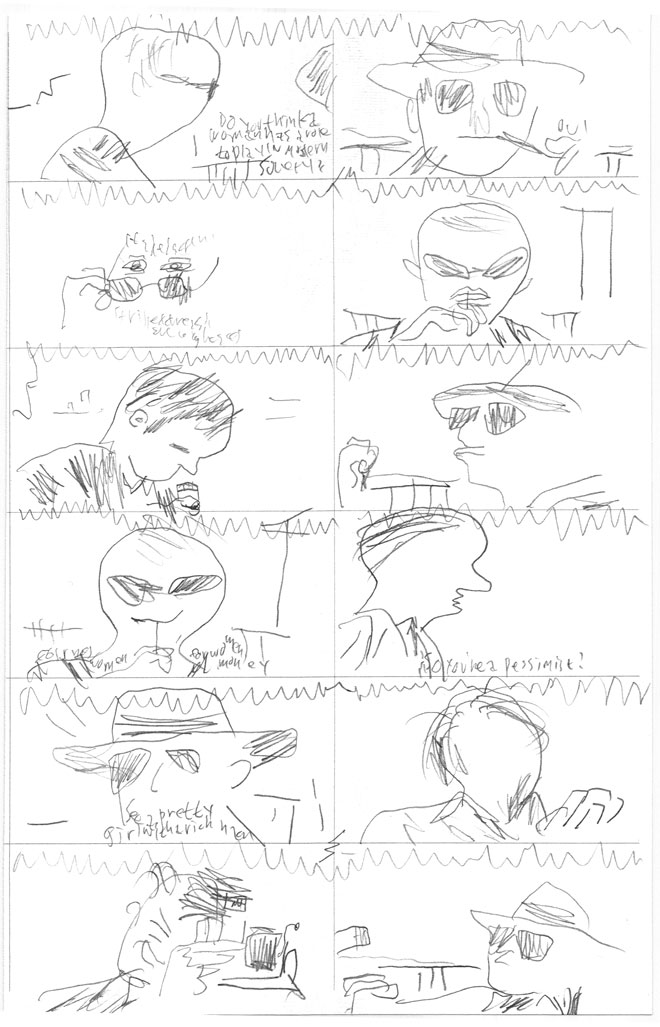

I said earlier that it’s difficult to criticize a work like this. This difficulty is not just in its subject matter, but also in its status as semi-memoir, a category that allows a work to gain significant power from the story of its creator. Regardless of how someone might feel about OTOND, there’s no doubt that it’s enriched by its proximity to Mizuki’s life story, which is truly remarkable. Mizuki is one of the most popular cartoonists in the world, having with his studio created thousands of pages of comics, and yet he did all of this after having lost his left arm in an air raid. He debuted at age 33, ten years later. His biography is inextricably bound to his war comics. When I reacted emotionally at the conclusion of the book, it was not just for the senselessness of the conflict, nor for the loss of Maruyama, who like most of the other soldiers in the book is very loosely characterized; it’s also for the connection of this character to the man who created him, mulling over all of the complex and contradictory reasons that Mizuki might send his stand-in to a death that he himself escaped.

But this connection is also problematic. Earlier in the book, when a character is killed attempting to eat a large fish alive, I found the sequence, and the explanation for the death, grotesque and unbelievable. But my reaction was quickly tempered by the thought: “This is a sort-of-memoir, right? He wouldn’t add something like that in unless it was true, would he?” And ultimately I have no way of knowing whether people have really asphyxiated from attempting to eat large live fish—but the reader’s likelihood of believing it is much greater because of that semi-memoir status. It’s that “semi” that’s so tricky.

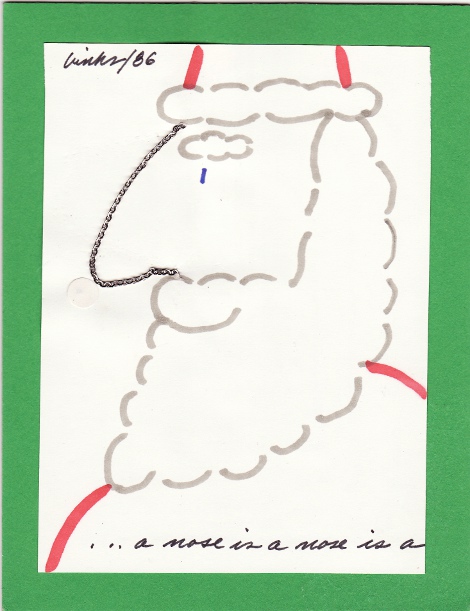

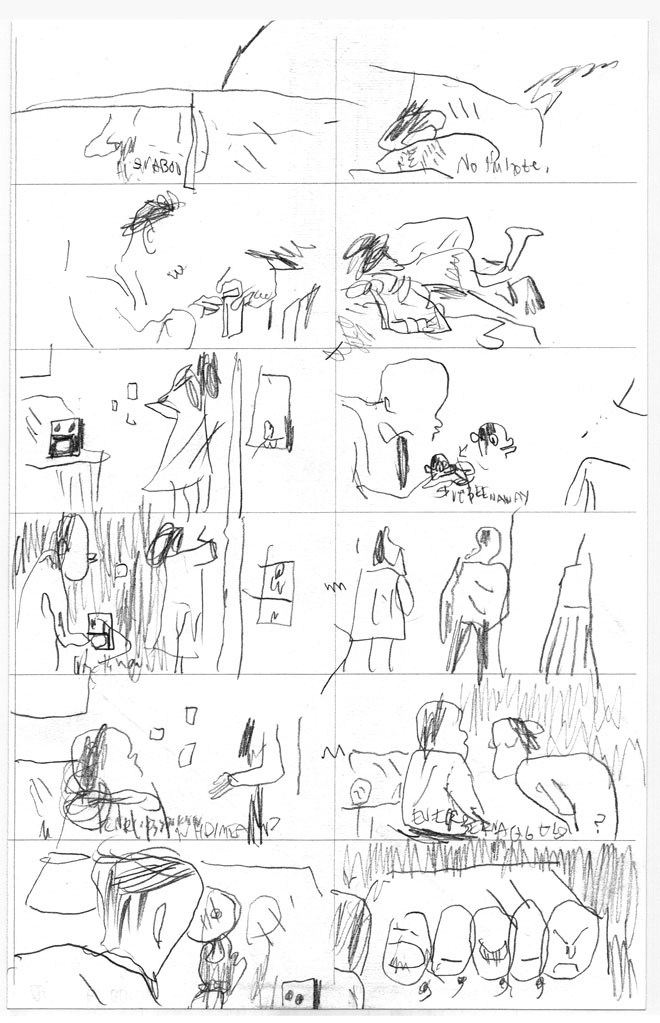

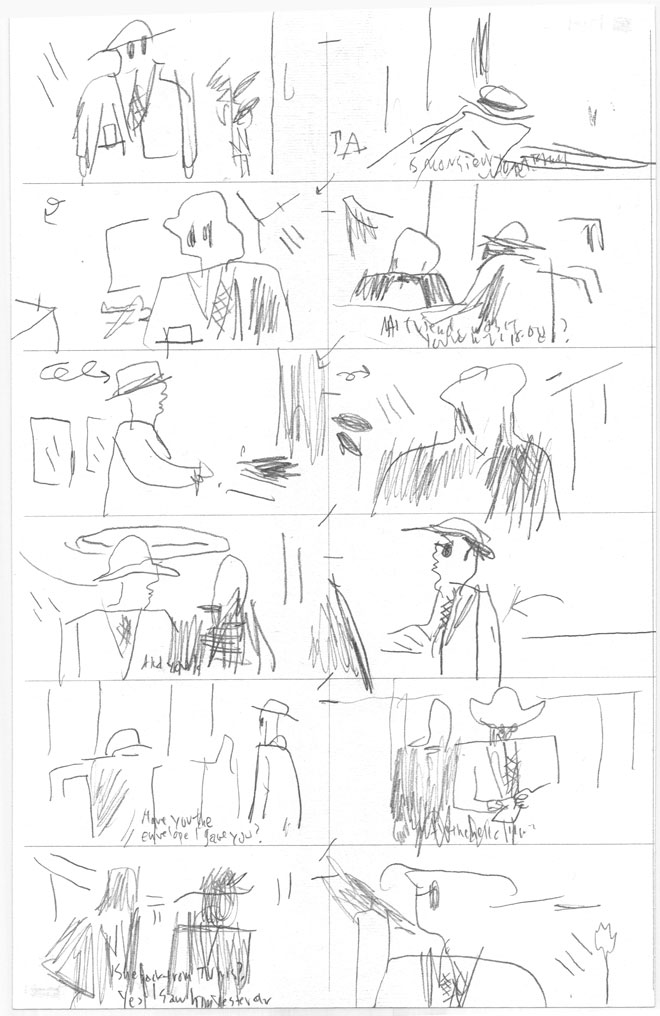

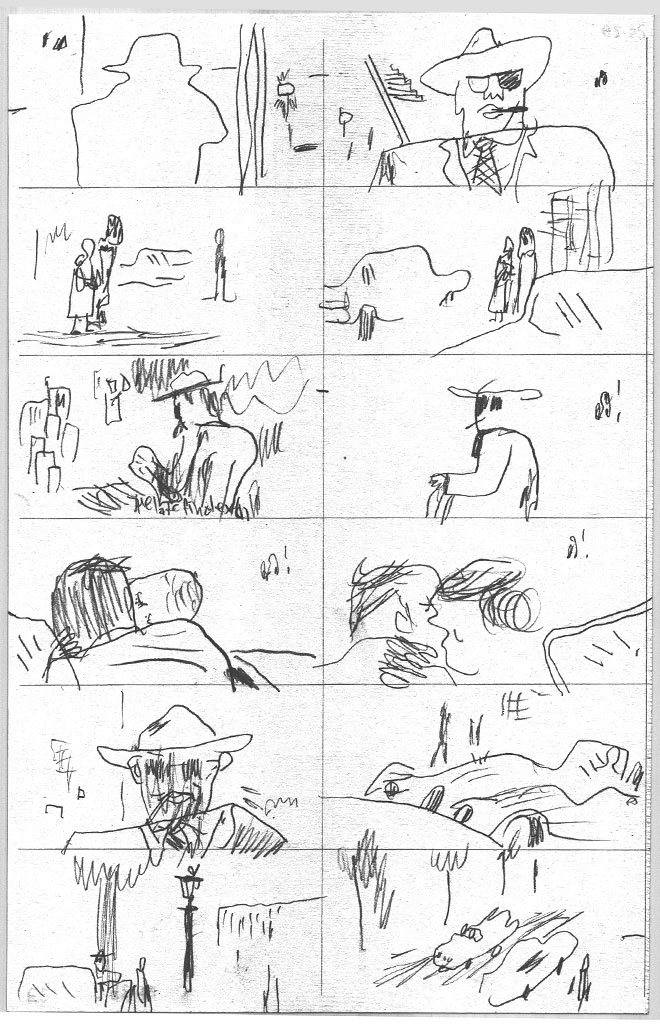

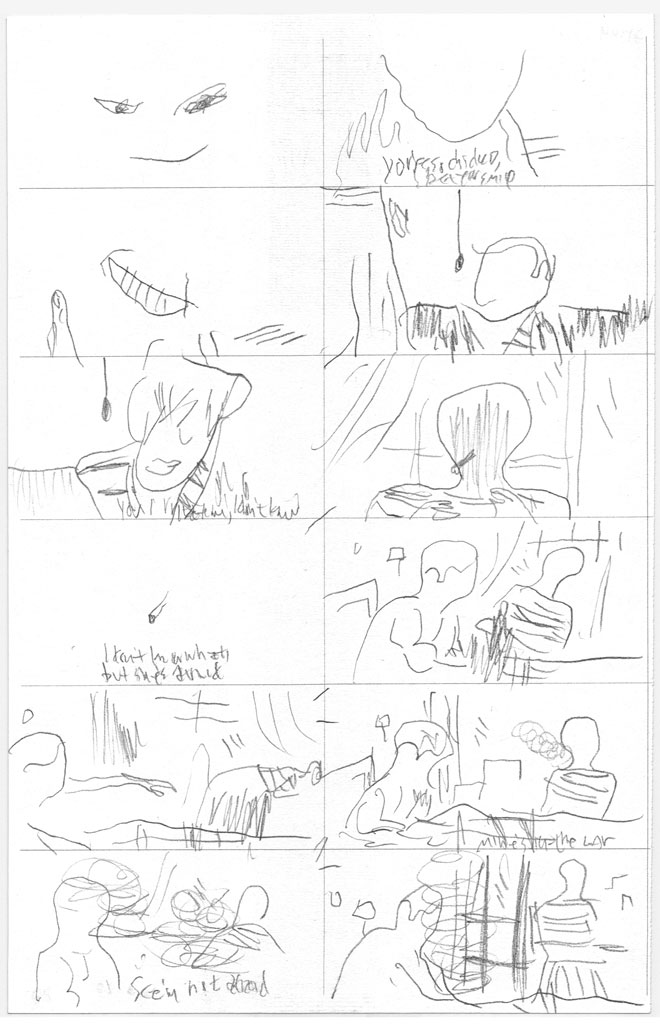

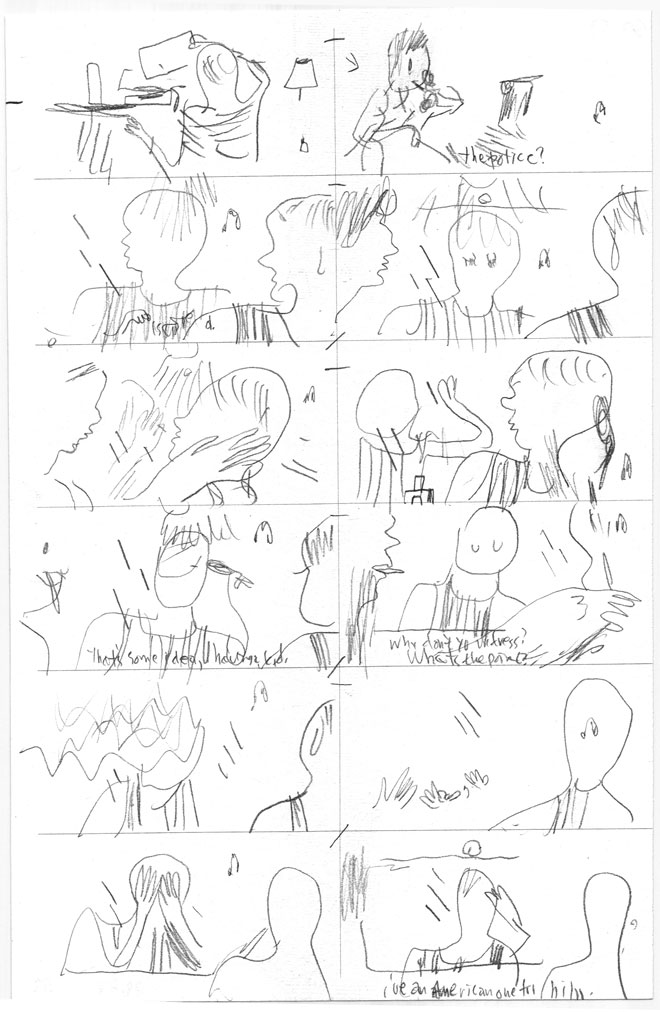

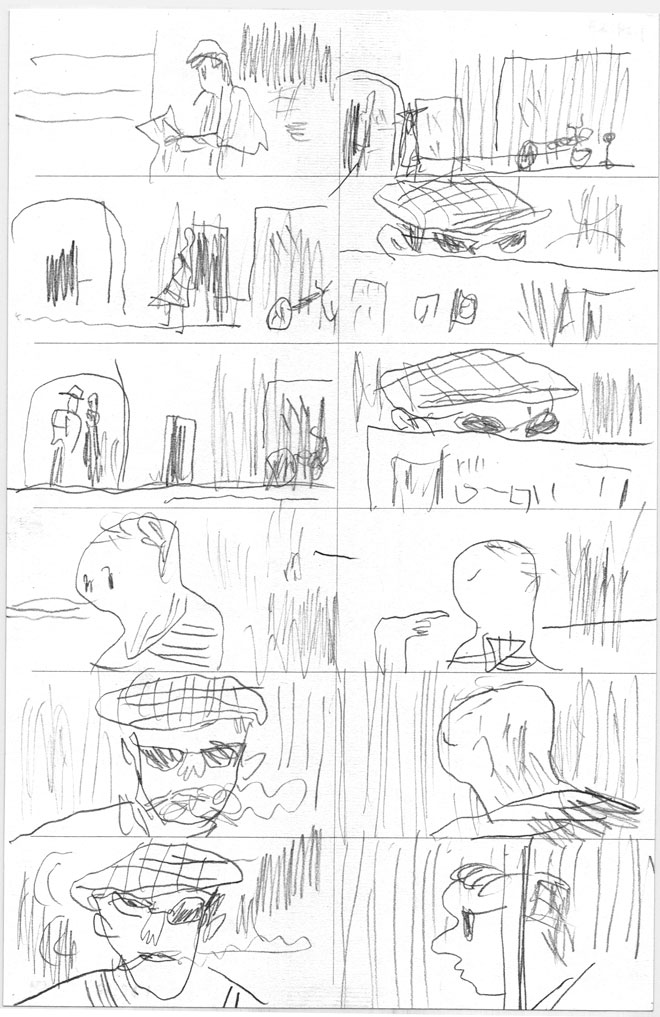

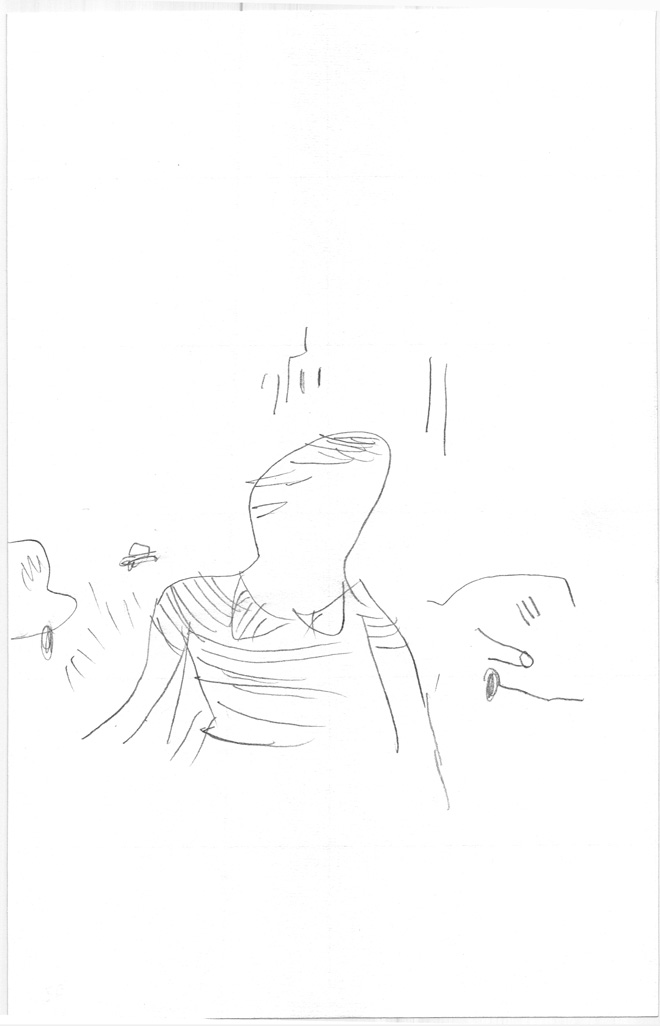

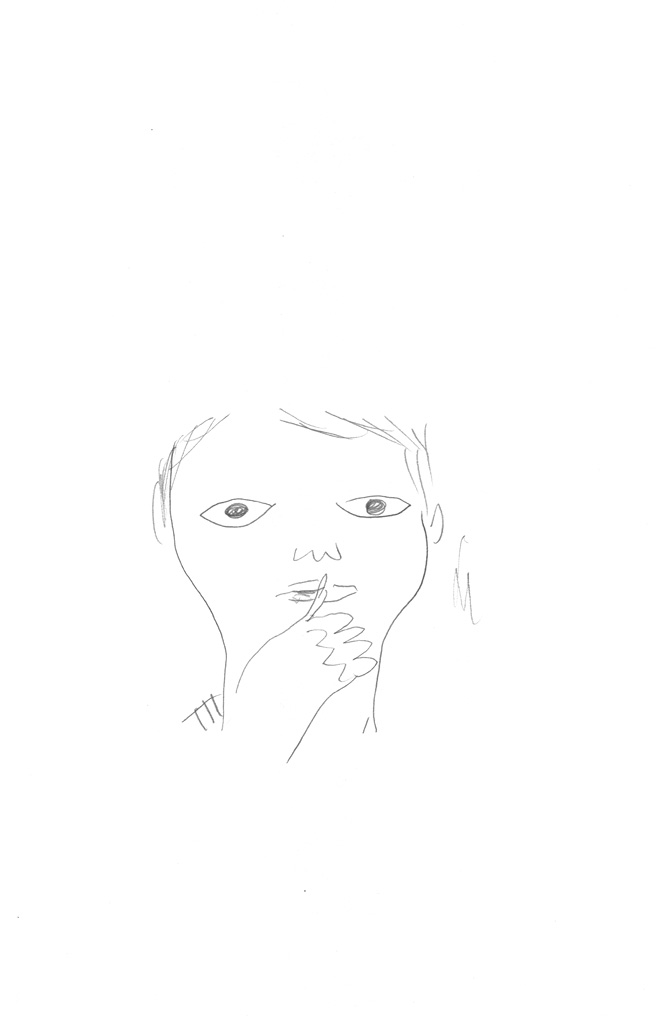

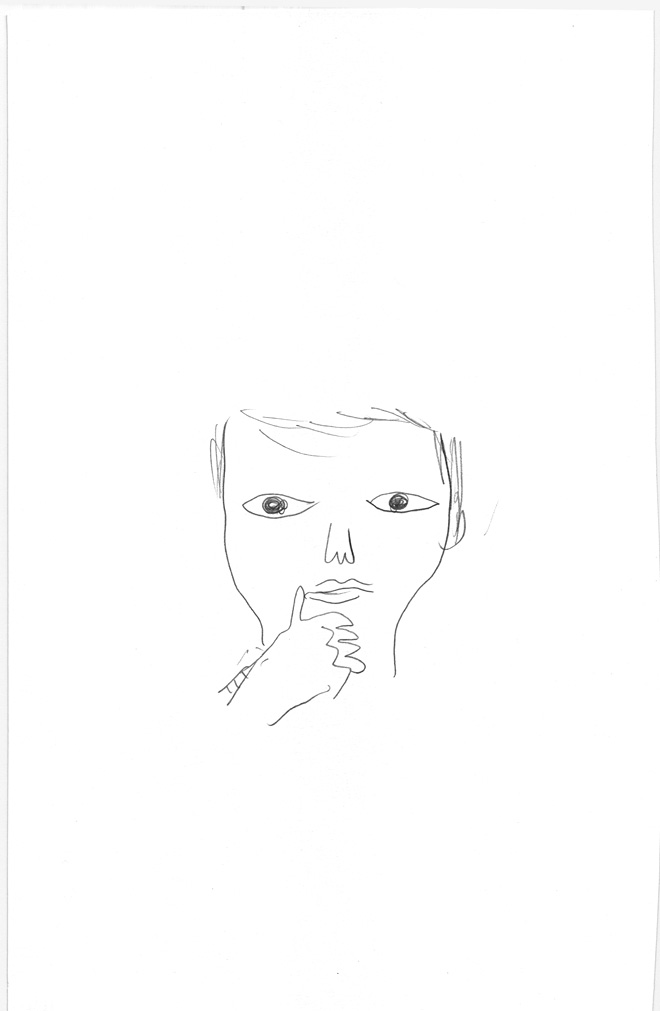

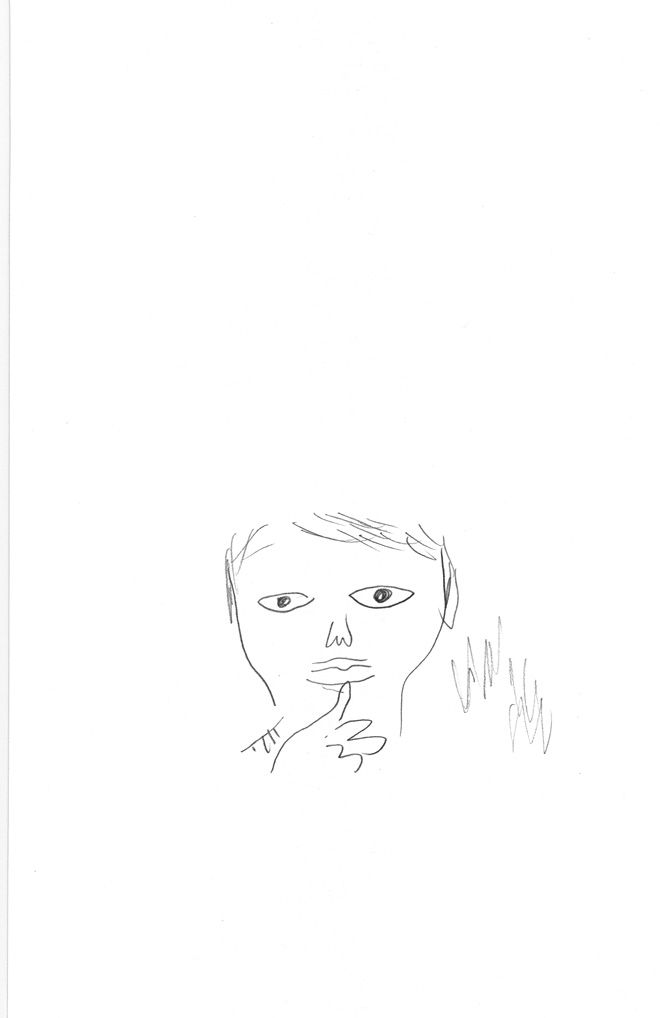

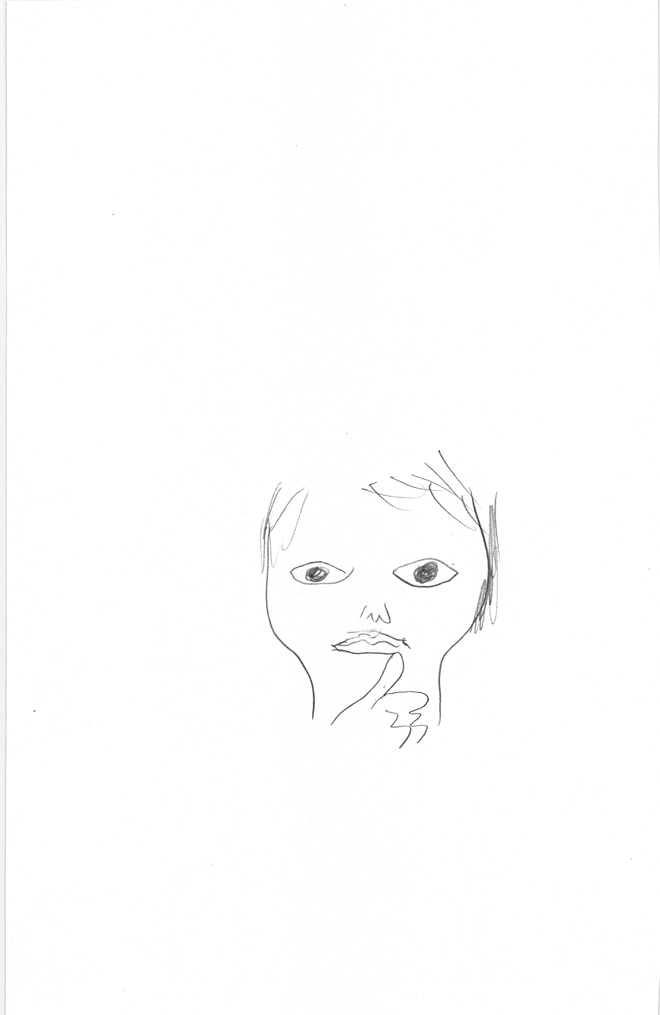

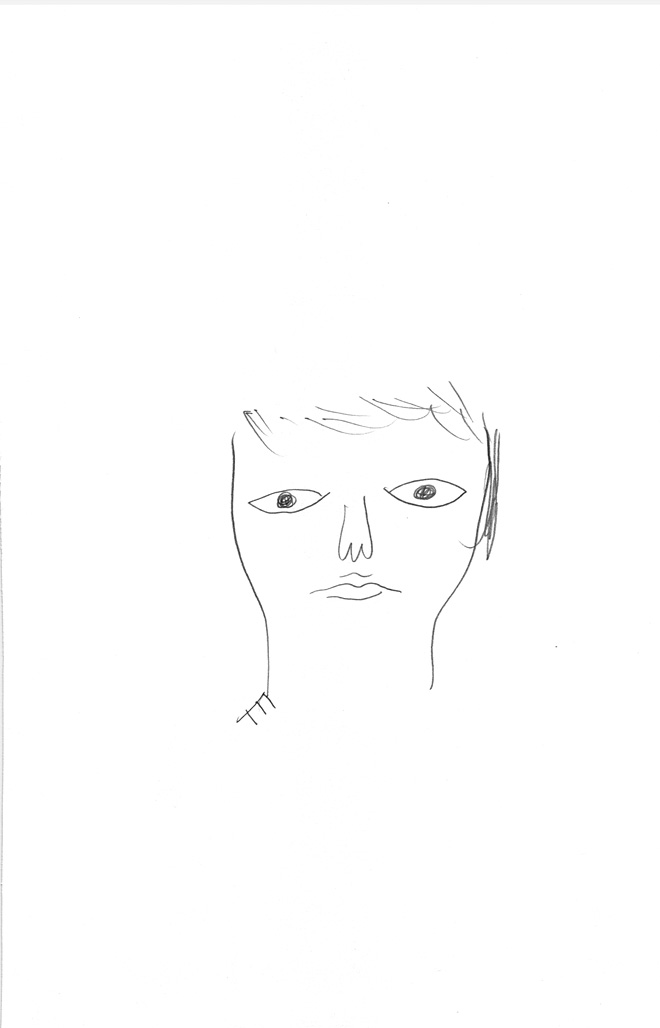

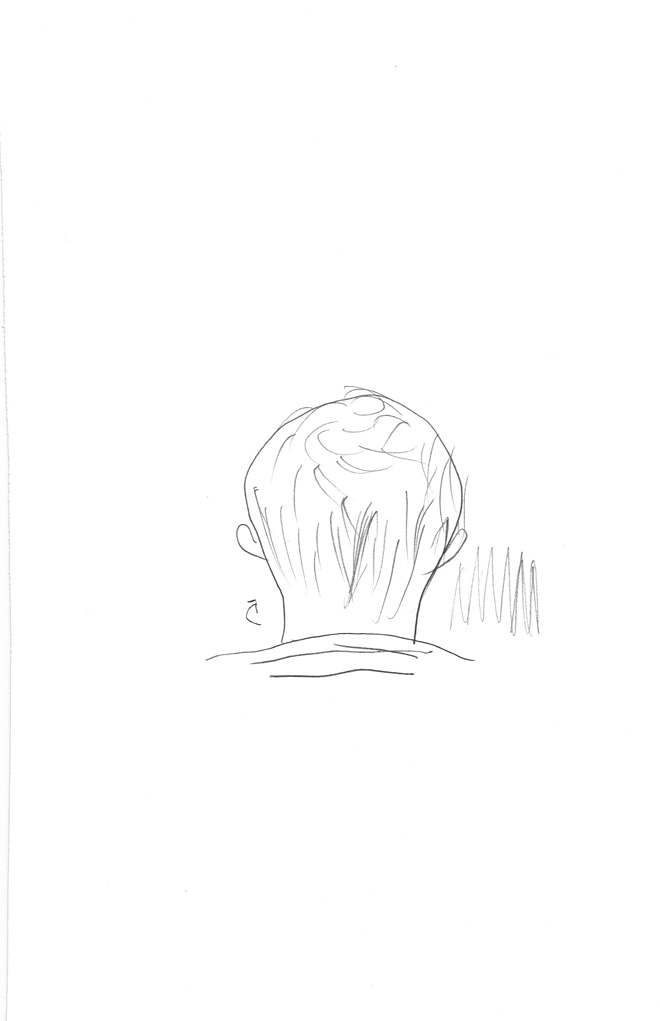

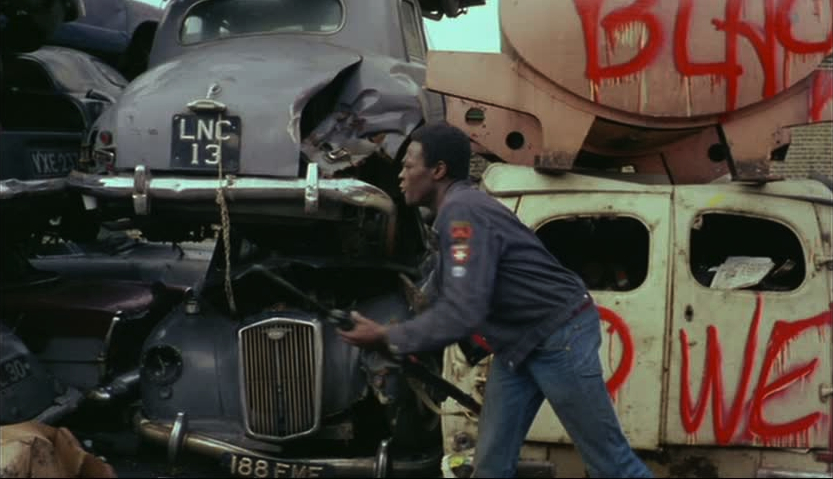

“An unintentional peek inside the process—a paste-up Mizuki head atop a photo-referenced body.”

“An unintentional peek inside the process—a paste-up Mizuki head atop a photo-referenced body.”

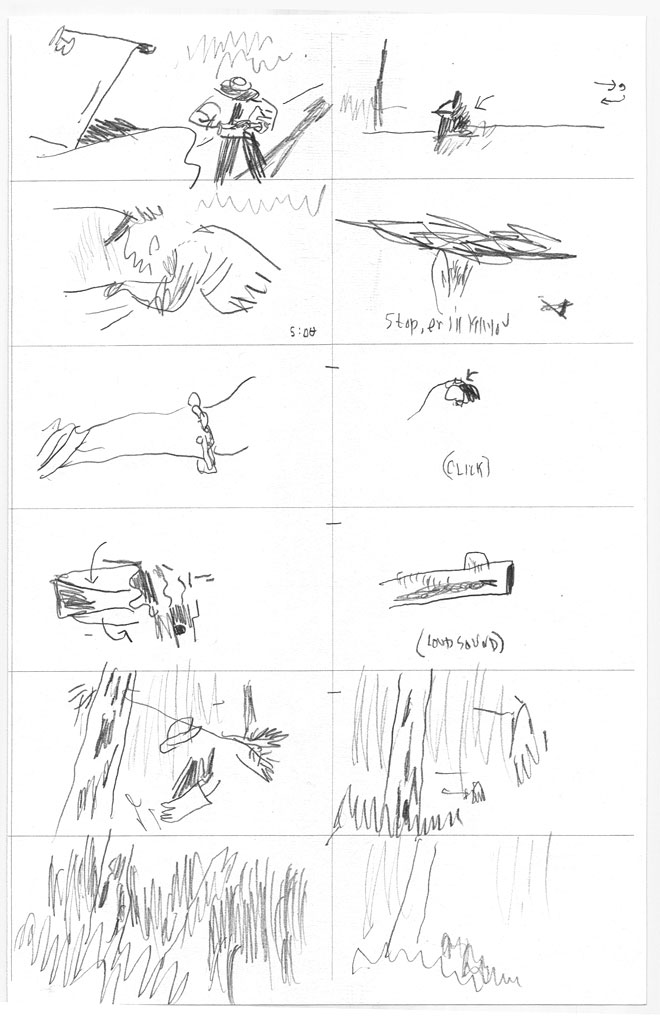

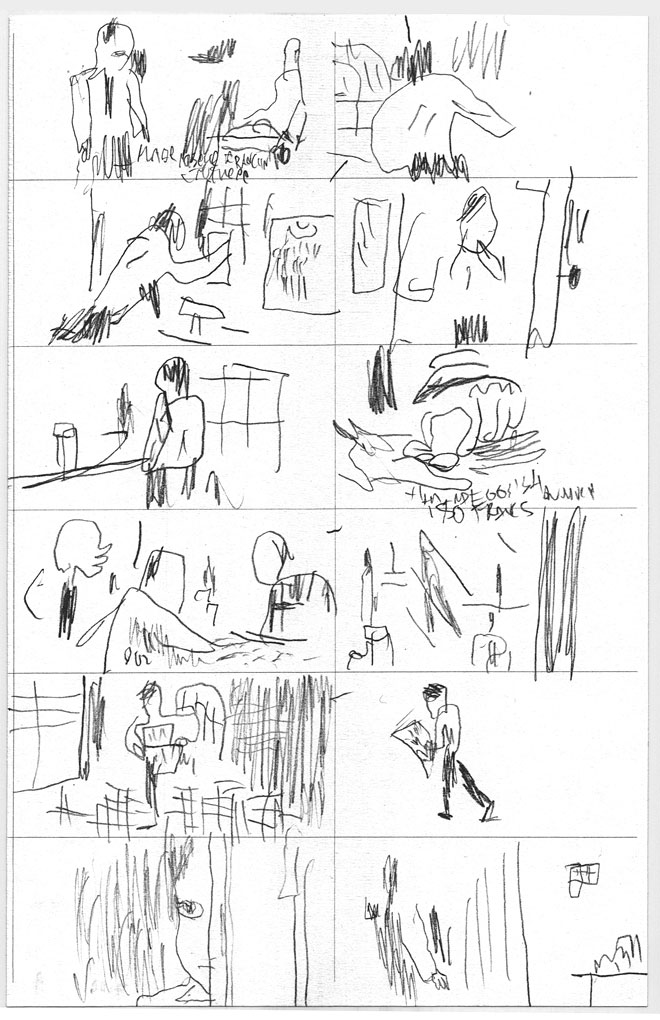

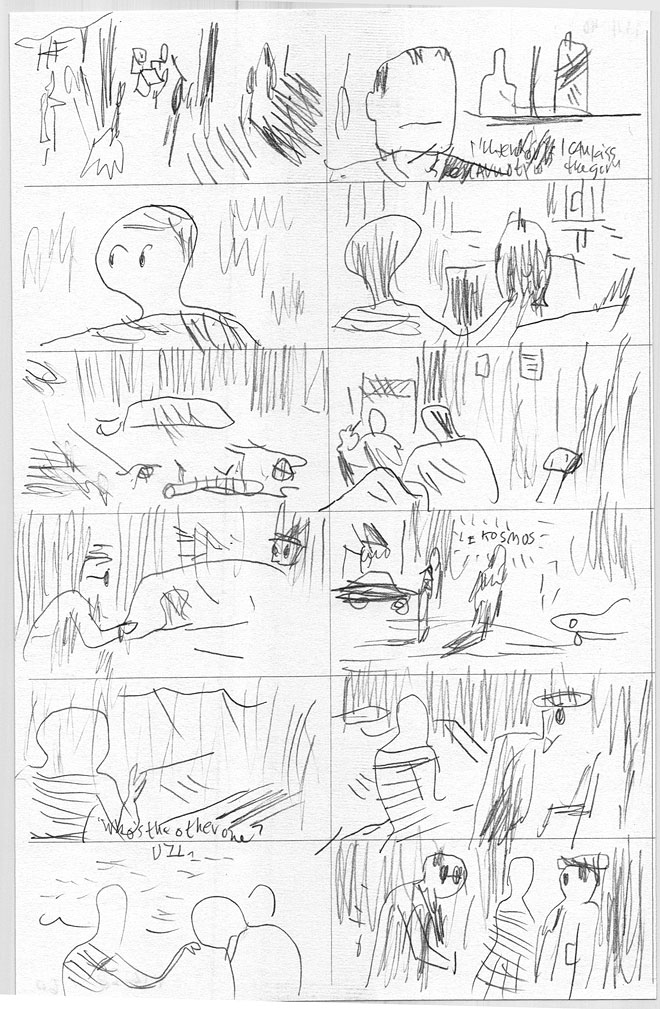

The visual style of the artwork can also be a stumbling block. The dissonance between the crude but communicative figures and the naturalistic, presumably assistant-drawn and photo-referenced backgrounds can be jarring at first, but soon works fairly well, at least for this reader. What’s problematic, though, is the hand-off—when characters suddenly leap modes, bouncy and expressive one moment, and photo-rendered and flat the next. This isn’t just a visual failing—it’s an opportunity lost. There were moments on my first read-through when I thought these translations of style would prove to be thematic—for instance, maybe the enemy would be rendered naturalistically, in the mode of the backgrounds and the hardware, personality-less, cold, and remote. But then the enemy would appear rendered in Mizuki’s style. Perhaps only the dead could have been rendered in this mode—certainly the transition into death at the end of the book is accompanied by this visual transition—but the power of this potential coherent visual statement is diluted by its use elsewhere. Ultimately I came to the conclusion that the decision to render some panels, and even only certain figures in panels, in this mode was most likely a pragmatic rather than artistic one; either assistants are rendering those figures or Mizuki himself is using photo reference. Either way, it is a major fault of a book that is otherwise very smart and deliberate in its decision-making.

Drawn and Quarterly’s adaptation has problems of its own, not the least of which is the unsympathetic and overly primitive lettering (“font design” is credited to Kevin Huizenga, but no one is credited with the lettering itself, perhaps understandably). Every sound effect in the book is rendered in the same font, which at its largest display sizes looks crude, wobbly and distractingly thick. The translation by Jocelyne Allen is readable, but has its own problems, including anachronism (the word “meh” out of the mouth of a Japanese soldier in 1943?), lack of clarity (a soldier is asked to “draw some cards” for his commanders, without any clarity as to what type of “drawing” might be indicated), and even outright error (the commander’s shifting rank). The translation is especially awkward in the area of the song lyrics that appear at numerous parts of the story.

This might seem like picking at nits, but these aren’t insignificant issues, considering this is in all likelihood the only English-language release this book will ever have. And to my mind, it is a compelling work by a major cartoonist who, like so many of his contemporaries, is woefully underrepresented in English. As for the visual inconsistencies, some would say that’s the price to be paid for volume production, the manga equivalent of television’s pragmatic cinematography, or indifferent musical scoring. Maybe it’s enough, after all, that this story is told, and perhaps it’s petty of people like me to pick at the details.

As for Mizuki himself, he’s long since moved on, his drawing time occupied primarily by manga about y?kai, for which he is widely known. But the past has a way of drawing you back. In 2003 he returned to Rabaul, where he had been held prisoner in the latter days of the war, where, after almost 60 years, he visited the islanders he had befriended during the war, the people that treated him with a humanity so strikingly absent from his commanders.

“We were […] creatures lower than a horse,” Mizuki writes in the afterword. “I wonder if surviving the suicide charge wasn’t, rather than an act of cowardice, one final act of resistance as a human being.”