A version of this article appeared on Splice Today in March.

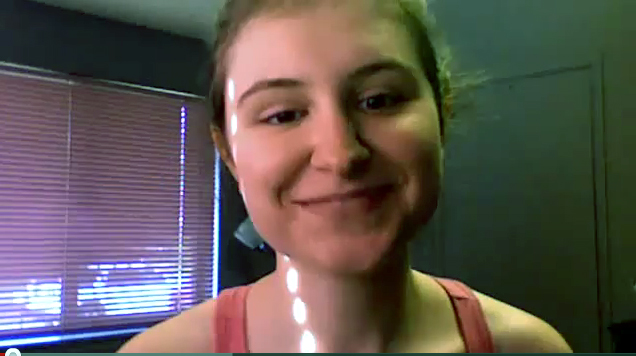

She recorded and posted the video quickly and impulsively—from concept to upload, the process took less than 20 minutes. Her eyes are gleaming and her face beams happiness and smug satisfaction. “God is such an amazing God,” she tells us, peering through the screen and into our eyes, so close to the lens that her face distorts. “On Wednesday, at the start of Lent, believers all over the world came together, and we have been praying specifically for God to open the eyes of atheists all over the world.” And, she tells us with excitement and pride, “Just a few days later, God shook the country of Japan. He literally grabbed the country by the shoulders and said, ‘Look! I’m here!’” TamTamPamela is overjoyed by the quick and emphatic response of her deity to her prayers, and encourages her audience to redouble their efforts. “Just imagine what will happen at the end of the 40 days!” she says with a beatific smile.

The video went live the morning of March 14, and began spreading almost immediately, thanks initially to a link on Ignorant and Online, a Tumblr account dedicated to “exposing the worst […] online comments, Facebook posts and internet posts. What was once anonymous is now revealed.” Started only two days before, Ignorant and Online had so far almost exclusively displayed screen caps of status updates of Facebook users linking the Japanese disaster to Pearl Harbor, or other off-color remarks related to the crisis. Perhaps it was her invocation of God, or the nature of video itself, but for whatever reason, this clip carried more weight. Within hours it was everywhere, and atheists and Christians alike seemed none too happy with the contents of the video.

That night I watched her YouTube channel with amusement, and then alarm, as thousands of comments flowed in, ranging from cries of “troll,” to threats of death, rape and pizza delivery. The alarm came when addresses, full names and phone numbers began appearing as well, first for a woman in Florida and then for another name in California. A sample of the comments:

b17ches like you makes me literally wanna start a crusade. mark my words that you’ll die a horrible horrible death.. — buyungwidhi

how about I fuck-start your face you stupid cunt.— heavysweater

Lady, if I held your head under the water for 17 minutes, I would quickly show that he either: A – Hates you B – Doesn’t exist— Notjustbonez

can anybody tell me who this girl is? name or location can help cause i can just look her up. Ill give her a religious wake up call myself and shoot this bitch.. private messg me any info on her. first person to do it ill give 1K. thanks— vietnameseJKT

you need to get raped — abaebae1

Yout such a dumbshit. fuck you get a fuckming life. i pray u fucking die u dumb bitch. i beleive that oh my god i cant begin how to think how much pain people will cause for u. your so fucking dumb. do understand anything? go die u fucking cunt. id llove to see u die. go to hell. do you not understand people are dieing. LETS ALL PRAY THAT YOU DIE! be encourage that god will crush you. Ill be overjoyed when you die — djmattzz1

Japan will come get u for this. — nova123

And then, just as suddenly as it had begun, it was over. TamTamPamela posted one last brief video, “Coming Clean,” in which she stated that she’s been “making troll videos for a while,” but that at this point she’s “kind of tired of pizza,” and so she’s calling it quits. Her account, along with all of her videos, disappeared shortly after.

Although deleting the account put out most of the fires, death threats and links to both somewhat correct and completely incorrect personal information continued to promulgate for days after the video. Surveying the wreckage, at the virulence of the reaction to her video, I tracked down the real person behind the character of TamTamPamela to find out, in her own words, what it’s like to be hated by a million people. What are the consequences of having your address and phone number, the names of your family members, even photos of your house linked to on dozens of web sites containing death threats on your life?

“Nothing,” she said over the phone, five days after having posted the most disliked video in YouTube history.

Really? Nothing?

“Nothing in real life,” she said, except that, “Tuesday morning a pizza was delivered to my house.”

Has anyone recognized her?

“If they did, they didn’t come up to me and say anything.”

A college student named Tam is the real-life person behind TamTamPamela, her self-described “character” that she played for more than a year on YouTube and on various religious message boards, both real and satirical. She was surprised by the reaction to her video, given that up until that point her videos had hovered around 10,000 views only. She ultimately outed herself, she says, because of the inaccurate private information being spread about the woman in Florida. “It wasn’t until late Monday night that my boyfriend told me that people were posting another woman’s information all over the Internet, saying the other woman was me,” she said. “And that was when I got worried. I started thinking that people were going to take this way too far.” Once she had outed herself, she said, there would be no point to maintaining the videos—the satire would be ineffective—and so she closed the channel.

I watched the year’s worth of videos before their deletion, and seeing them chronologically, one can see the rapid development of the craft of satire. The early videos are rambling, meandering, rarely getting to their central topics right from the start but instead approaching the arguments as part of a larger fabric of personal history. As they progress Tam warms to her character, and the videos have a lot more direction, arriving at the theme early and spending the bulk of the time developing the concept. One video discusses the season of Lent, and how it is the will of the Holy Spirit for TamTamPamela and her dog, Rambo, to fast together for the entirety of the 40-day period. In another video TamTamPamela has been visited by an angel who told her that she “must pass on this message to the sinful people of Massachusetts. If you don’t vote for Scott Brown today, God will be very angry. The wrath he poured out on Haiti, the wrath he has poured out over the world in small doses—let those be an example to you. Don’t give God a reason to be angry. Vote for Scott Brown.” In a more vulnerable moment, TamTamPamela reaches out to her YouTube audience and asks them for advice about how to resolve her impasse—the Bible instructs her to obey her husband in all things, but her fiancé doesn’t want her posting any more videos. She knows the Holy Spirit has instructed her to continue her evangelization. What’s a good Christian girl to do?

But something was different about the Japan video. Part of the reaction was undoubtedly due to its proximity to the crisis itself, but some of the extremity could come from the craft and the delivery of the satire. Almost all of the previous videos have slight tells to clue their audience into the intent. “I always had the same people watching and the same people commenting,” Tam said. “There were two groups—the one group that would watch it and argue amongst themselves whether I was being serious, and there was the other group who knew my intention was to bring attention to the subject of the video.” The difficulty of determining the authenticity of statements of a religious fundamentalist nature is a well-observed phenomenon—called Poe’s Law, named after and coined by Nathan Poe: “Without a winking smiley or other blatant display of humor, it is impossible to create a parody of fundamentalism that someone won’t mistake for the real thing.”

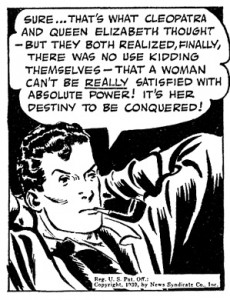

In fact, if there is a “tell” in TamTamPamela’s penultimate video, it’s that most fundamentalists aren’t as direct in general conversation about these kind of feelings, and certainly not on video. That doesn’t mean that those thoughts still aren’t there or expressed. The earthquake connection readily brings to mind Pat Robertson. In 2010, shortly after the devastating earthquake in Port Au Prince, Haiti, Robertson had this to say on his show, 700 Club:

… something happened a long time ago in Haiti—people might not want to talk about it. They were under the heel of the French, you know, Napoleon III or whatever, and they got together and swore a pact to the Devil. They said, ‘We will serve you if you free us from the Prince.’ True story! And the Devil said, ‘Okay, It’s a deal.’ And they kicked the French out, the Haitians. But ever since that they’ve been cursed by one thing after another. They’ve been desperately poor…. They need to have and we need to pray for them a great turning to God, and out of this tragedy I’m optimistic that something good may come.

It’s a spectacular bit of reasoning, tying the woes of a stricken nation to the perceived Godliness of its people. And, for a Bible literalist, it’s a perfectly reasonable position as well. If one believes that God has agency in the world, that He in fact has opinions about the conduct of the human beings he has created and rewards them and punishes them in turn, it’s natural to assume that such a devastating event is in fact the will of that deity. This assumption is made explicit throughout the Bible, as God selectively destroys individuals, cities, kingdoms, and at least once, the entire world. In fact, the Bible instructs those faithful to God to carry out the work of eliminating unbelievers for him:

If you shall hear say in one of your cities, which the LORD your God has given you to dwell there, saying, Certain men, the children of Belial, are gone out from among you, and have withdrawn the inhabitants of their city, saying, Let us go and serve other gods, which you have not known; Then shall you inquire, and make search, and ask diligently; and, behold, if it be truth, and the thing certain, that such abomination is worked among you; You shall surely smite the inhabitants of that city with the edge of the sword, destroying it utterly, and all that is therein, and the cattle thereof, with the edge of the sword. And you shall gather all the spoil of it into the middle of the street thereof, and shall burn with fire the city, and all the spoil thereof every whit, for the LORD your God: and it shall be an heap for ever; it shall not be built again.

— Deuteronomy 13:12-16, American King James version

Did Tam approach her videos from an atheistic perspective? Like much good satire, it’s hard to pin the perspective down completely, but Tam sees herself as religious. Yet, “I really don’t like calling myself a Christian, because these people who are the face of Christianity have painted Christianity in such a terrible light.” From her perspective, the satire is directed at “the Christians who really don’t care what’s going on around them, and the kind of people who are representing them. Most Christians would never blame these natural disasters on God. But these same Christians let these crazy wackos lead them and let them be the face of Christianity. I kept posting the videos because I wanted to bring to light that if we actually followed these leaders, this is what we would be saying.”

Her faith did not seem to change the digital wrath directed at her, wrath similar in tone to the wrath God has instructed his people to visit upon the unbelievers. Reading the words directed at her, it’s hard not to see the reaction as the wrath of the righteous. And yet, in this world of screens and distance, of pulsing light and little physical proximity, what does the righteous indignation of a million people mean? Thousands of threats of death and rape. Your name and address and phone number. A single pizza, turned away at the door.

Tam is guilty of poor taste—she is guilty of indiscretion, and of tremendously bad timing. But mostly, she’s guilty of not winking at the camera often enough, and not couching her character’s speech in the language of diplomacy.

Professional provocateurs, meanwhile, have the line down perfectly, and know how to use indignation and outrage to gain audience and advantage. The same day that TamTamPamela’s love letter to God spread across the Internet, Glenn Beck shared his thoughts about the crisis with his radio audience of millions.

I’m not saying God is, you know, causing earthquakes … Well, I’m not not saying that either. [Laughing.] What God does is God’s business. I have no idea. But I’ll tell you this—whether you call it Gaia or you call it Jesus, there’s a? message being sent. And that is, ‘Hey you know that stuff we’re doing? Not really working out real well. Maybe we should stop doing some of it. [More laughing.]

Negative reaction to Beck’s calculated raving was mostly of the “what type of God would kill thousands of innocent people to punish them?” variety of indignation. Well, if you are a Christian or Jew who believes in the literal truth of even a fraction of your religion’s holy scriptures, then the answer is simple—your God kills people innocent of all but not loving him. He instructs his followers to do the same. Much worse than that, he’s set up a system of eternal torment to punish the slain unbelievers and sinners of all other stripes. That kind of petulance makes Beck, or even TamTamPamela, look like the very model of grace and understanding.

Not actually existing has advantages: TamTamPamela will suffer no eternal torment. But though she’s passed, her creator lives on. “I’m still definitely going to keep doing what I’m doing. I’m not going to stop,” Tam said. “It’s in my nature to troll people, to get a reaction out of people, to say, ‘Look, you see what’s going on, why don’t you do something about it?’ ”

Isn’t she worried about reprisal? What about applying for jobs in the future—isn’t she worried that searches using her full name might turn up all of this material? She reminds me that her state of residence has a law forbidding hiring discrimination based on religious affiliation. So she might be in the position of defending her character’s viewpoints in order to get a job? She laughs. Seriously, I tell her, the stuff I’ve written has been seen by such a small fraction of the people that have seen your videos, and yet I have constant anxiety about someone out there calling me out for the asshole I am, hating me for what I’ve written. Do you just get used to the hate? Are you and I just built differently?

“Everyone always says that it’s part of my natural personality to have that ‘I really don’t care about anything’ [attitude],” she said, her normally fast cadence of speech slowing down slightly. “But I know what people are like in real life versus the way they are on the Internet.” She paused, and then spoke again, a smile in her voice. “And I think I’m the perfect example of that.”