Ana Hatherly, The Writer (1975).

Still in shock after seeing that the comics’ subculture continues as deaf and insular in its aesthetic criteria as ten years ago (since the infamous The Comics Journal’s list) not having moved one iota, I remembered Dwight Macdonald who, in Politics Vol. 2, No. 4 (Whole No. 15), April 1945, wrote:

It would be interesting to know how many of the ten million comic books sold every month are read by adults.[…] We do know that comics are the favorite reading matter of men in the armed forces, and that movie Westerns and radio programs like “The Lone Ranger” and “Captain Midnight” are by no means only enjoyed by children. […] This merging of the child and grown-up audience means [an] infantile regression of the latter unable to cope with the complexities of modern society.

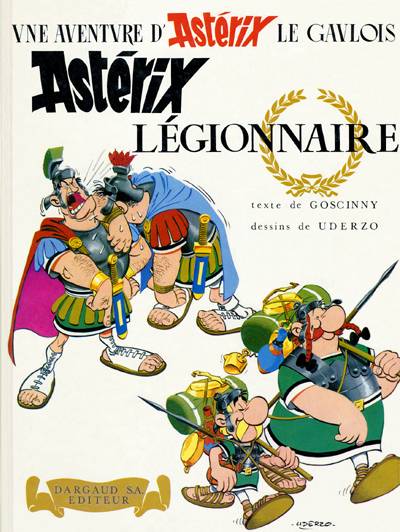

I certainly don’t agree that an infantilization of grown-ups’ cultural habits means that people can’t cope with the complexities of modern society, it may simply mean that comics readers want (for a while) to escape those complexities. Hell, I suppose that they want to escape life itself, or, at least, those parts of life that can’t be depicted by kitsch… Did you notice how death and exploitation are almost completely absent from this top ten’s list (and I don’t mean death of a Daffy Duck kind; Maus and the death of Speedy are an exception)? Have you noticed how lifeless these comics are? (And I mean “lifeless” in the sense of not related to life in any way – Dwight Macdonald also helped me to realize this when he said to Pauline Kael, when they were discussing North-American films: “How did vitality get in there? I mean, crudeness I give you, but vitality? It’s possible to be crude and not vital, you know?”)

I couldn’t agree more with David T. Bazelon, who, also writing in Politics (Vol. 1, No. 4, May 1944), wrote:

“Superman” gives vicarious satisfaction to explicit social frustrations. It cannot be tragic or displeasing, nor can it contain that essential realism which is a quality of all good art. For it has a purpose: this is art in the service of social neuroses. And that service is the meaning of most comic strips… Pearls are produced not by serving but by opposing disease.

Only now did I understand the true meaning of the phrase “comics are not just for kids anymore.” What it really means is that popular comics, even if they continue to be children’s comics, are also enjoyed by adults. With the above phrase and other similar ones people from inside the ghetto of the comics subculture want to sell a false image to the laymen and laywomen (it was now definitely proven to me that the above reading is the right one or they’re lying).

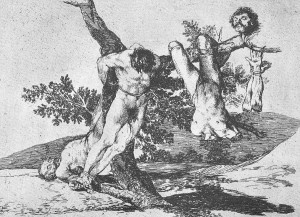

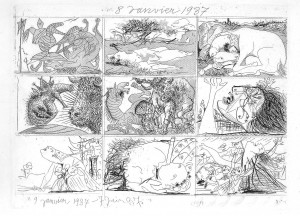

Francisco de Goya, The Disasters of War (published in 1863).

I’m not saying that The Hooded Utilitarian’s top ten list (and beyond) is completely devoid of value. As I put it last May 10 on this very blog: I have nothing against popular entertainment. I also think that a good art vs. bad art kind of black & white view of things isn’t exactly clever or productive. I enjoy a lot of pop pap (Gasoline Alley, for instance) it’s just that I don’t think that it fares well alongside Tsuge’s work or Fabrice Neaud’s work. That’s my whole point, while the pap is canonized meatier work is forgotten.

I suppose that one could say that even meatier work (if that’s possible) is also not included, but there, the infantilization of the reading public is not the only barrier. Essentialism is frontier number two (an even more powerful one this time).

Rosalind Krauss wrote an important essay about how perplexing the concept of sculpture had become at the end of the seventies: Sculpture in the Expanded Field (October, Vol. 8, Spring, 1979). I borrowed her concept of an extended field and applied it to comics.

Rosalind Krauss criticized historicism in her essay. Historicism is also a problem in comics’ expanded field’s case for two reasons: (1) because my field expansion is in great part ahistorical; (2) because some critics view comics as an unchanging art (Alan Gowans) or a posthistorical art (David Carrier).

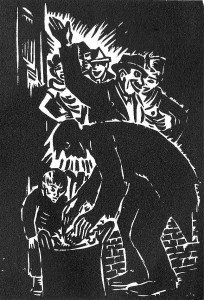

Frans Masereel, From Black to White (1939).

Arriving here I can only go on after an analysis of what I called, the origin’s myth and the problem of a comics definition.

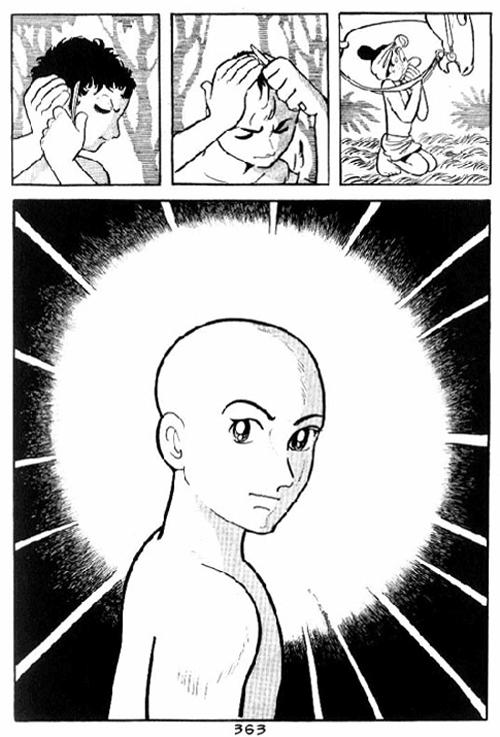

There are, at least, five cultural fields which can help to expand comics as an art form: (1) Medieval (or older art) painting and book illustration; (2) the wordless engraving cycle; (3) Modern and Post-Modern painting; (4) Concrete and Visual Poetry; (5) the cartoon. None of these fields are linked to comics on the gentiles’ heads. For a variety of reasons they all have problems to be accepted by the comics milieu as well. Let’s briefly examine some of these objections:

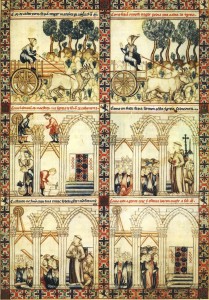

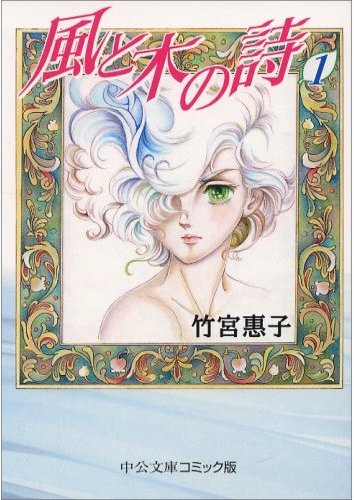

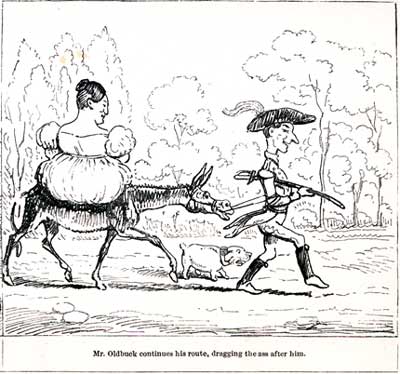

1. Medieval comics (let’s call them that way) weren’t produced for the enjoyment of the people: they weren’t reproduced, they were highly expensive items, they were owned by aristocrats. Since the beginning of fandom comics have been viewed as popular art: a child of the Industrial Revolution and modern visual mass communications (hence: comics were born in America with the publication of a Yellow Kid page in the New York Journal: “The Yellow Kid and His New Phonograph,” October 25, 1896; this is a position that American scholar Bill Blackbeard always defended). Besides this sociological criterion we must add two formal ones in this particular case: the existence of juxtaposed panels and the existence of speech balloons. Denying the latter some European scholars (Thierry Groensteen and Benoît Peeters, for instance) argued that comics started with Rodolphe Töpffer’s first “Histoires en estampes” (Histoire de M. Vieux Bois was drawn in 1827 – Histoire de M. Jabot was published in 1833; Töpfferians who are also print fundamentalists must say that Jabot was the first comic, other Töpfferians will say that Vieux Bois is the real McCoy). In his book The Early Comic Strip (1973) historian David Kunzle argued that the first comics were created shortly after the invention of the mechanical printing press by Johann Gutenberg (Hans Holbein’s Les Simulacres et historiées faces de la mort is among the first books that he cites, but his most famous example is Francis Barlow’s A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish Plot, c. 1682). David Kunzle later converted to Töpfferism (More recently he published a book titled Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe Töpffer (2007). Barlow’s two pages fulfill Bill Blackbeard’s criteria, by the way: they were printed, they have a grid, they even have speech balloons or something similar (Robert S. Petersen called them “emanata scrolls”).

Anon., Canticles of Saint Mary by Alfonso X the Sage (c. 1270).

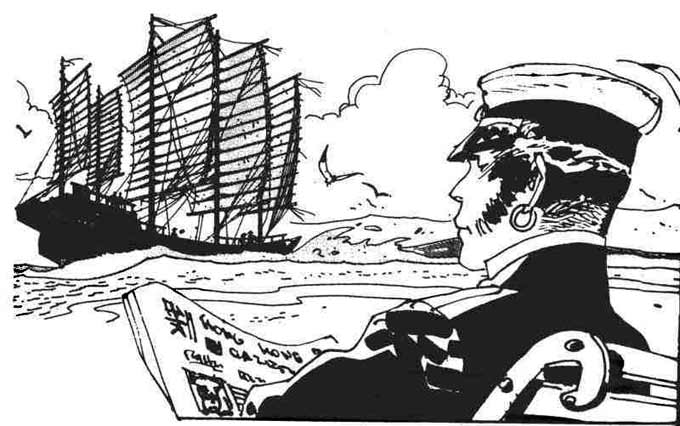

2. Engraving cycles, from Jacques Callot to Eric Drooker, aren’t as difficult to accept (in the comics corpus) by the comics milieu as Medieval illustrations. This happens because they were born from an idea that art should be more democratic: engravings are cheaper than paintings and sculptures. Even so the high / low divide may be a serious objection here. Even if Frans Masereel had a leftist sensibility and his cycles were (are) published in book form, he was a serious painter, he was in the wrong side of this sociological fence. If I defend Picasso as a comics artist the comics milieu calls me a snob and an elitist (doing their usual mind reading they say that I want to include highly regarded gallery artists in the comics canon just to elevate comics’ status). Formal features are a problem also: engraving cycles have no speech balloons or page grids.

Jacques Callot, The Miseries and Misfortunes of War (1633).

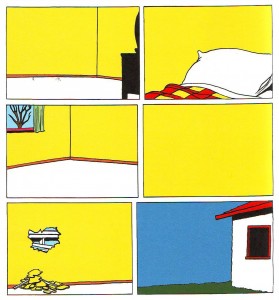

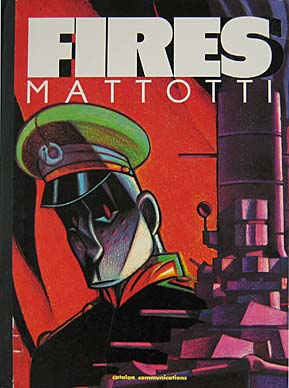

3. To the comics milieu paintings and poems (visual or otherwise) are not comics, period. Original comic art has been exposed in galleries, museums, and comics conventions (a strong tradition in Europe’s comics conventions gives original art an important role as an attraction factor), but I don’t mean that. What I mean is comic art meant to be exposed as unique objects on gallery walls. Most people would call these objects paintings inspired by comics. Don’t take my word for it though, the artists themselves call “gallery comics” to what they’re doing. Sorry to indulge in name-dropping, but I mean: Christian Hill, Mark Staff Brandl, Howie Shia. Andrei Molotiu could also be part of this list, I suppose; ditto Paper Rad: they all have strong links with the comics milieu. As for Brazilian painter Rivane Neuenschwander, American painter Laylah Ali and Swiss painter Niklaus Rüegg, I have no idea, but both Ali and Rüegg are interesting examples because, not only did they paint, their paintings were also original art (in the comics sense) for the publication of comic books (by the MOMA and Fink Editions, respectively).

Niklaus Rüegg, Spuk (2004); a Carl Barks comic without the characters.

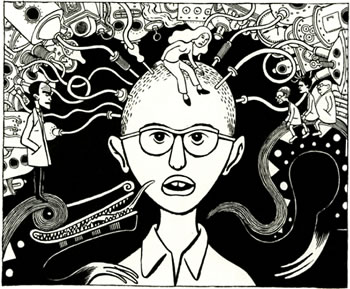

4. During the fifties Brazil was at the avant garde of poetry. Inspired by Stéphane Mallarmé’s Coup de dés, Guillaume Apollinaire’s calligrammes, Dadaism, Ezra Pound’s Imagism, Haroldo and Augusto de Campos, Decio Pignatari, Pedro Xisto and others created Concrete poetry. In a Concrete poem typography and the pages’ space is as important as words. Sounds are more important than meaning (or new meanings are born when words are reorganized on the space of the page and reinvented). Concrete and visual poetry viewed as comics may prove that comics without images may exist in the same way as comics without words.

Álvaro de Sá, Process-Poem (c. 1967).

If we consider stained glass windows as comics (something that is not as far-fetched as it seems) Medieval comics were also meant to be viewed by “the masses” even if they weren’t printed (David Kunzle opines differently though: “A mass medium is mobile; it travels to man, and does not require man to travel to it.”) As for grids and speech balloons it’s possible to find said features in Medieval comics, believe it or not. Here’s what Thierry Groensteen wrote on the Platinum List (Jan 18, 2000):

Danielle Alexandre-Bidon, a specialist of the Middle-Age, has given a lot of evidence of the fact that comics existed in the medieval manuscripts, during the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries. Hundreds, if not thousands of pages, with speed lines, word balloons, sound effects, etc. The language of comics had already been invented, but these books were not printed. After Gutenberg, text and image were not so intimately linked anymore, and one could say that the secret of comics was lost, until Töpffer rediscovered it.

This is revealing: even the most fervent defender of Töpffer as the “father of the comic strip” says here that he “rediscovered it.” This is something like saying that Columbus rediscovered America (he couldn’t discover it simply because he found people already living there when he arrived).

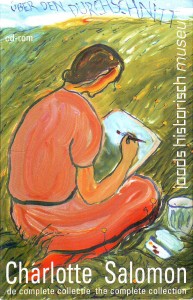

The comics origin’s myth is essentialist: it’s an arbitrary choice that’s based on an equally arbitrary definition (the latter precedes the former). (And I’m sure that I’m not the first one to say this, elsewhere or around here.) The two more common (or so it seems to me) kinds of definitions are based on social (comics must be reproduced and distributed to the masses) and formal premises (essential characteristics of comics are sequentiality, word and image relations, the word balloons, the juxtaposition of the panels, etc…). Social definitions of comics have two problems: (1) The sorites paradox applied to the concept of “masses.” If one grain of wheat doesn’t make a heap two grains of wheat do not; […] if three thousand grains of wheat don’t make a heap three thousand and one grains of wheat do not; etc… When do we stop not having a heap to finally have one? This paradox can be applied to print runs. (2) Social definitions of comics are usually used to deny that Medieval comics are comics (they aren’t reproduced). What I say is that they must have been reproduced at some point because I’ve seen them and I have never seen any original drawings. There’s a third point: how come an original comics page is not a comic, but an exact repro is? Leonardo de Sá cleverly argued this point saying: the original art is not a comic the same way as the repro of a painting is not a painting. Not bad, I would say… but… using Nelson Goodman’s theories about fakeable and not fakeable arts, painting is one-stage autographic while comics are n-stage (my theory) autographic. That’s why a repro of a painting is not a painting while the original art of a comics page is a comic. Formal definitions of comics have problems also; I’ll mention two: (1) Any formal definition arbitrarily chooses some features and forgets others. This means that, if I chose to say something like “the speech balloon is essential to comics” (oops, there goes Prince Valiant) or “word and image relations define comics” (oops there go “mute” comics out the window) no comics exist at all. Why? Because all comics have panels without speech balloons, without words, etc… A comics reading experience would be something like this: now it’s a comic, oops, now it isn’t, etc… (2) All art is based on experiment. More inventive artists are always pushing the limits of their art forms. Comics are no exception, but if we put a formal corset around them what happens is that: (1) we lose some very important artistic achievements (some who defend comics exactly because they’re mass art couldn’t care less, obviously, but I, for one, do) and (2) we seriously limit the creativity of the artists who chose to create comics. Another problem is that we can’t look back to, let’s say, Charlotte Salomon, and view her work as comics (again: some who defend comics…). It seems that all comics have sequentiality, but even this point was argued by Eddie Campbell in a discussion with yours truly many moons ago: he included one panel cartoons in the comics concept. Me?, I have no definition of comics whatsoever. I prefer to say with Saint Augustine: If no one asks me, I know what they are; If I wish to explain them to him who asks, I do not know.

Charlotte Salomon, Life? or Theater, CD-Rom (2002 [1940 – 42]).

So, denying essentialism we can look back or look around and find great comics. I have no solution for the ahistoricity of the expansion in time or social space. Picasso didn’t view himself as a comics artist (even if he liked comics) and the art world around him didn’t either. However… if older art historians say that Picasso’s Songe et mensonge de Franco (Dream and Lie of Franco) are engravings (which they are, of course) more recent ones (Juan Antonio Ramirez, for one) say that it is a comic. This means that we (even if part of this “we” doesn’t belong to the comics milieu) may look in unexpected places and notice multiple instances that can be considered comics (Frans Masereel is a no brainer by now, for instance; I’m sure that Paleolithic painters didn’t call “painting” in the modern sense to what they were doing). As for comics as an unchanging or posthistorical art it may be true (I have my doubts) if we consider it as low mass art, but aren’t we excluding heaps of alternative artists, then? I’m trying to be reasonable, but, to talk frankly, I’m tempted to say that this is utter nonsense.

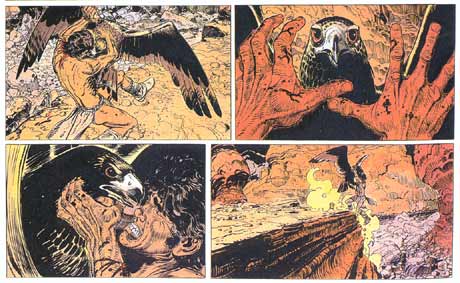

I didn’t vote for any artists and work on the expanded field (maybe Martin Vaughn-James’ The Cage counts as part of it; Robert tells me that there were indeed some votes in said field: Cy Twombly, Max Ernst, and a few others), but if I did almost all my ten choices would be in that category, I’m afraid… Who, in the comics’ restrict field can rival Callot, Goya, Hokusai, Picasso? No one, I’m sure… Not even George Herriman and Charles Schulz.

Pablo Picasso, Dream and Lie of Franco (1937).

Note: huge chunks of the above text were previously posted on my blog The Crib Sheet.