From The Real, The True, and The Told: Postmodern Historical Narrative and the Ethics of Representation, by Eric L. Berlatsky, now available from The Ohio State University Press.

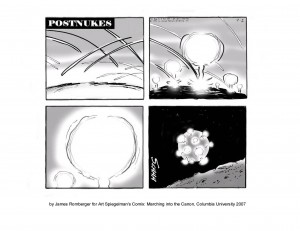

Preamble: The below is an excerpt of chapter four of the book, entitled “It’s Enough Stories”: Truth and Experience in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” The book itself has very few images from Maus (two actually), due to copyright permissions expenses and red tape. The below section had no images, but I’ve included some low resolution pics for this online excerpt. This constitutes about a third of the chapter—itself about 1/6 of the book. The “Works Cited” is a selection from the larger one in the book. It’s possible some sources were left out and that some listed are not referred to in this section. Click on the images for a larger view (in most cases).

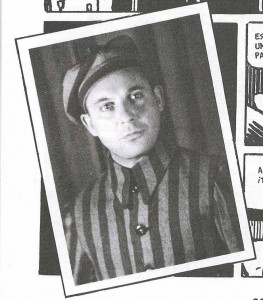

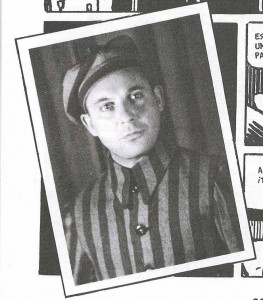

(…) Likewise, a photo of Vladek included near the close of Maus II shows him in a concentration camp uniform, but it is revealed in the course of the narrative that it is not his own, but a mock one used at a “photo place” for “souvenirs” (134). That is, the “realistic” picture of the Vladek of the camps can only be produced afterwards, staged for the purposes of memory: a simulacrum of a past that is already, thankfully, gone. Maus, then, uses photographs not simply as a means of establishing a mimetic attachment to the historical past, but also to suggest the ways in which all media are subject to staging and manipulation, distancing us from the referent they claim to reproduce.[1] While cartoon mice are quite obviously not “true” copies of their human surrogates, Maus illustrates how photographs may be no closer to their referent. As Marianne Hirsch writes, “Spiegelman lays bare the levels of mediation that underlie all visual representational forms” (11). The occasional and increasing use of drawn photographs that remain true to the animal metaphor alongside the “real” photographic reproduction of human figures only serves to blur whatever boundaries may remain between the purportedly real photograph and the definitively constructed drawing (Maus 17 and Maus II 114-115).

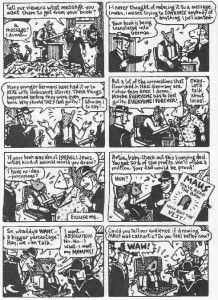

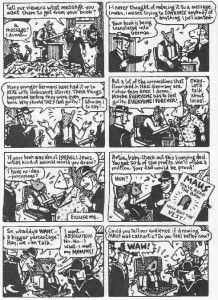

From all of this, it is clear that although Artie dramatically excoriates Vladek for distancing him from Anja’s past, Spiegelman performs a similar task for the reader, indicating to us how any representation of the past is more mediated, and therefore distant, than it may initially appear. In fact, not only are Spiegelman’s representations far from the reality they initially appear to reflect, but they continually run the risk of asserting ideological control. Like the Nazis’ depiction of Jews and Vladek’s redeployment of his Holocaust memories to justify his racism, Spiegelman is sure to implicate himself when he depicts Artie at the outset of chapter two of Maus II. Sitting at his drawing table, in front of television interviewers, Artie discusses the commercial success of the first volume of his book while sitting atop a pile of anthropomorphic mouse corpses. He is depicted not as a mouse, but as a man wearing a mouse mask, performing Jewishness for commercial gain. The simultaneously humorous and threatening depiction of the American advertiser offering a license deal for Artie vests (“Maus. You’ve read the book now buy the vest!” [42]) indicates how Artie (and Spiegelman himself) uses the past not merely to recall it in the present, but for his own profit and on the backs of the Jews his book is purportedly “remembering.” Artie displays a questionable connection to the past in order to participate in the circulation of power and profit.[2]

It is for these reasons that Artie questions his whole project when, on a visit to his therapist, he quotes Samuel Beckett in saying, “‘Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness’” (Maus II 45). Here, Artie notes how any attempt at speaking, witnessing, or portraying history runs into not only the impossibility of finding the historical real, but also into the ethical difficulties that suggest that any representation is an act of power and oppression. The therapist, Pavel, inspires Artie’s observation when he says, “…look at how many books have already been written about the Holocaust. What’s the point? People haven’t changed…Maybe they need a newer, bigger Holocaust” (Maus II 45). Here, Artie and Pavel seem to reject representation in two ways. First, Artie promotes a complete withdrawal from signification, preferring silence and nothingness. Second, while Pavel is clearly commenting on the dark side of human nature, his remark also suggests that a return of the referent (a newer, bigger Holocaust) would be preferable, since a repetition of the event itself would no longer be a representation of it, but the thing itself, independent of the ethical and epistemological dilemmas Artie raises. Elsewhere, Artie also voices a desire to have been at Auschwitz himself, “so I could really know what they lived through” (Maus II 16).[3] While Artie eventually withdraws this wish, it is indicative of the kind of paralysis that a poststructuralist view of representation can induce. Artie’s epistemological and ethical despair leads him to wish for silence or renewed genocide, neither of which seems artistically or ethically productive. Nevertheless, Maus’ representational despair is supplemented and complicated both by its commitment to traditional historical accuracy and by its capacity to convey Ankersmitian experience through the media of both memory and history. Given all of these doubts and recriminations about the possibility of historical representation, one wonders why such care is taken by Spiegelman in “getting it right,” or how it is possible that so many readers praise Maus precisely for its truthfulness.

Maus as/and Memory

Pavel’s rhetorical wish for a “new Holocaust” indicates a desire, even a desperate yearning, for the materiality of the referent that is not uncommon in contemporary theory. This possibility is not limited, however, to Pavel’s fantasies about the referent’s literal return, but is often, particularly in the context of the Holocaust, configured in terms of the opposition between history and memory. As Jonathan Boyarin observes, the postmodern attempt to delegitimate “universal history” has, at times, led to the reification of memory and the effort to understand history and memory as “fundamentally different modes of relating to the past” (93). In the previous section, I discuss Maus’ treatment of the past without making a significant distinction between these two “modes,” but given the fact that Vladek personally remembers the Holocaust while Artie comes to the same material belatedly, like a historian, collating, arranging, and fact-checking documentary evidence, it is a crucial distinction and one that bears further examination.

If traditional history presents us with unified events, “sponging […] all diversity off of them” in an effort to create “coherent comprehension” (de Certeau, Writing 78), memory, due to its individual nature, resists this unifying effort at social definition, at least according to some theorists.[4] According to proponents of memory, it can resist history’s retrospective reconstruction of the past that tells only a single story. That is, because memories are typically (if not always) conceived of as individual and unique, they are by their nature not integrated into a larger institutional or cultural narrative that defines the “self” of the culture and marginalizes or oppresses its “others.” The power of memory is likewise linked by its proponents with the capacity to make the referent of the past present, as opposed to merely creating a representation of the missing. It is for this reason that, for theorists like Pierre Nora, memory overcomes the debates over Holocaust representation. Instead, memory is often seen as something else entirely.

“Memory and history, far from being synonymous, appear now to be in fundamental opposition. Memory is life, borne by living societies founded in its name. It remains in permanent evolution, open to the dialectic of remembering and forgetting, unconscious of its successive deformation, vulnerable to manipulation and appropriation, susceptible to being long dormant and periodically revived. History […] is the reconstruction, always problematic and incomplete, of what is no longer. Memory is a perpetually actual phenomenon, a bond […] to the eternal present; history is a representation of the past” (8).

Similarly, Maurice Halbwachs notes that memory focuses on that which is continually present, repeated, and “essentially unaltered,” while history focuses on the rupture between the past and present (85-86). For Nora and Halbwachs, the past is not gone in an ontological sense as long as it is remembered and memory keeps alive any slivers of the past that remain in its grasp. If a historian writes an account of the Holocaust, it is merely a representation of the past, separated from its “presence,” or essential being. If a survivor, like Vladek Spiegelman, remembers the Holocaust, however, it is, in some sense, present (“eternally”) and real (“perpetually actual”). While both memory and history are, then, prone to error, manipulation, and appropriation, only one transmits the referent of the past, while the other “refers” to it with the compromised tools of signification. It is for this reason that personal memory retains some authority over the proliferation of textuality and electronic media so pervasive in contemporary society. Ankersmit’s account of Aristotelian impressions on the wax of the mind, or Freud’s “mystic writing pad” seem, in fact, to support this notion. The mind that remembers retains the impression of the past, carrying it into the present. This may help to explain the collective Jewish impulse to “witness” through memory the events of the Holocaust. Indeed, first-hand accounts are typically called “testimonies,” a name tied closely to the “legal process of establishing evidence in order to achieve justice” (Young, Writing 28). That is, the sense of “testimony” as authoritative is linked to the notion that the truth of the past is integral to the possibility of justice in the present. Such a belief is amply reflected in both the Yale Fortunoff and Survivors of the Shoah Foundation collections of videotaped survival “testimonies.”[5]

Michael Staub pinpoints the contradictions within the impulse to collect memory-work, however, indicating that the faith entrusted to these memories more accurately reveal fears about the loss of a connection to the past, than an effective means of accessing it.

“[T]hey reflect a general anxiety over the impending death of all concentration camp survivors and their living memories. When they are gone, we will have mountains of written texts, videotapes, films, recordings, and other evidence. But the actual voices will be lost forever. How, then, to approximate the authority of the oral in a world increasingly suspicious of […] written evidence?” (35).

Staub’s “authority of the oral” identifies an attempt by many to hold on to Nora’s notion of a “continuous present” carried through individual memory. History, from this perspective, can only be a second-hand, prosthetic addendum to memory’s witnessing of the past. While “writing” may be the most-cited prostheses that intercedes between the source of the past and its immanent memory, Staub notes how our contemporary age is replete with alternative prostheses, or texts: videotapes (and now DVD’s and YouTube files), audio tapes (and now CD’s and mp3’s), films, etc. Each of these, it is suggested, can only approximate the oral and the remembered, which are implied to be versions of the referent itself.[6] This division between the oral and the written is, of course, one of the earliest targets of Derridean deconstruction in “Plato’s Pharmacy,” some twenty years before Nora offers the distinction, and it is useful to consider how poststructuralism blurs the distinction between these modes of relating to the past.

In the Phaedrus, Plato privileges memory, the “real,” and the internal retention of the past over and against any prosthetic version that might be aided by writing. Derrida, however, rigorously illustrates that this distinction can only be arbitrary since “[t]he outside is already within the work of memory […] A limitless memory would in any event be not memory but infinite self-presence. Memory always […] already needs signs in order to recall the non-present with which it is necessarily in relation” (Dissemination 109; emphasis in original). That is, memory is not a pre-linguistic internal recreation of past events, but is already a process by which “signs” are used to approximate the “real” of the past, and always unsuccessfully so. Memory is writing in the sense that it is the use of signs to “represent” that which is no longer there. A “limitless self-presence” would entail a timeless subject whose past is also its present and therefore also its future. Such a subject does not exist outside of theoretical physics. Likewise, if memory did not partake of signs, a memory of the Holocaust would bring it back into being, reviving a referent better left behind, despite Artie’s occasional wishes in Maus.

Memory, then, according to poststructuralist logic, is not what Nora claims, but is what he defines as history, a “representation of the past” with no claim to a “presence” that we can know without mediation. In fact, writing and history’s prosthetic character is not its most threatening attribute, according to Derrida. Rather, it is threatening because it can breach the perceived internal self-presence of the subject. Plato voices the concern that writing will sap the internal capacity of the thinker to remember without its aid, indicating that writing is not actually irremediably external to the truth of the past, but that it can invade the inside, weaken, or destroy it. As Derrida points out, writing is then already inside, since memory is a process of signification, not a reproduction of the past. It is for this reason that the “line between memory and its supplement [writing], is more than subtle; it is hardly perceptible” (Dissemination 111). Here, the distinction between memory and history proposed by Nora and Halbwachs dissolves. While it is hopeful to conceive of memory as a “present” alternative to the re-vision that history offers, the notion of memory’s “presence” is a false one, since both are merely signifiers of a referent long gone. The only thing “present” in the mind of s/he who remembers is the “absence” characterized by signification, a “trace” of the past without its object: “a pseudo-trace, a detritus, a re-ferent, a carrying back to/from a past that is so completely decontextualized, so open to recontextualization, that it […] becomes […] an emblem of a past evacuated of history” (Crapanzano 137). From a poststructuralist perspective, memory is no different from history.

Maus as/and Narrative

At first blush, Maus performs the same deconstruction of the memory/history binary as Derrida does in “Plato’s Pharmacy.” Initially, we are given the first-hand witness and the seemingly immanent memory of Vladek in opposition to the second-hand and prosthetic history of Artie. However, while Artie and Vladek’s versions of the past are competitive, they are similar in terms of their distance from the historical referent. Read through an Ankersmitian prism, however, the similarity of memory and history does not have to mean that neither have the capacity to convey the truth and/or experience of the past. Rather, it may mean that both do. A look at Maus’ treatment of narrative and non-narrativity helps elucidate this possibility.

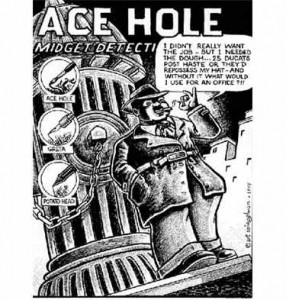

Interestingly, Spiegelman’s attitude towards, and public statements about, narrative are filled with ambivalence. In many of his early comics (“Ace Hole, Midget Detective,” “The Malpractice Suite,” “Don’t Get Around Much Any More”), Spiegelman is largely uninterested in telling a “story.” Instead, they serve more as commentary on the medium itself, pushing the boundaries of the comics’ page’s paradoxical and simultaneous presentation of multiple sequential temporal images (narrative) and a single static atemporal one (non-narrative). In a 1982 interview in The Comics Journal, Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly observe that plot is largely just a “conventional formula,” a “comfortable matrix”,” and “manipulation” (Groth, Thompson, and Cavalieri 45-47). Nevertheless, Spiegelman admits that he doesn’t “think comics can be non-narrative” (55), principally because that which separates comics from painting, still photography, and other visual art is precisely the juxtaposition of sequential images. Without sequentiality and temporality, the medium of comics does not exist. Despite this observation and his consistent admission that Maus is “narrative in every sense of the word” (Groth, Thompson, and Cavalieri 36), Maus retains an antipathy for elements of plot. While the book(s) certainly tells a story and formally embraces narrativity in ways that Spiegelman’s previous work did not, it retains a critique of narrative, and particularly its tendency to “comfort,” to make meaning out of the meaningless, and to obscure the historical truth.

In Maus, then, Artie partakes of various textual prostheses (tapes, photographs, history books) in order to connect with the past. It soon becomes evident, however, that Vladek too is distanced from his own experience by a less concrete prosthesis of signification: narrative. While it is true that poststructuralist philosophy might focus more closely on language as that “text” that neither Vladek nor Artie can escape in their search for a referent, narrative is more clearly the problem that Maus addresses, as it is for Hayden White and postmodern historiography more generally. Ankersmit, for instance, even in his earlier, more radically relativist, period, was willing to concede that while individual statements about the past can be true, narratives present thornier problems and yield greater results since they present us not with a collection of statements about the past, but with a proposal about what those statements mean.[7] It is this meaning-making quality that White argues arises from “emplotment,” the transformation of events into a narrative. This problem is most clearly articulated in Maus in Vladek’s efforts to provide closure to his Holocaust experiences after being reunited with Anja.

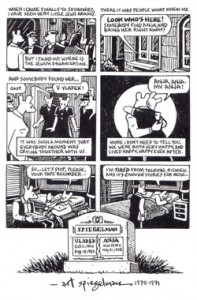

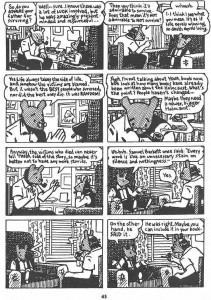

On the final pages of Maus II, Vladek recounts his return to Sosnowiec, Poland, and his reunification with Anja after their time in concentration camps. As Vladek describes the encounter, “It was such a thing that everybody around was crying together for us […] More I don’t need to tell you. We were both very happy, and lived happy. Happy ever after” (Maus II 136). While the moment is poignant, reflection on the rest of the book reminds the reader of the fallacy of Vladek’s statement. While he may well have been happy at the moment of the reunion, all readers know that they do not live “Happy ever after,” given Anja’s 1968 suicide and all that follows. The presentation of that suicide in “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” gives the reunion a different meaning when made a part of Maus.[8] Spiegelman’s explicit rejection of “fatuous attempts to give [the Holocaust] a happy ending” (Dreifus 35) must, in this context, be read as a rejection of his father’s Romance “plot,” and perhaps of “plot” generally conceived.

As Arlene Fish Wilner points out, Vladek’s oral narrative is specifically configured not only as memory, but also as “story,” subject to the perils of emplotment. The idea of the “authority of the oral” is belied by the ways in which the oral too is dependent upon narrative structures that assert meaning where none inherently exists. Vladek’s account also indicates the problematic role closure plays in narrative representation. While the reunion itself undoubtedly occurred, its placement within a narrative, and particularly at the end of a narrative, gives it a meaning that is conspicuously misleading. In Metahistory, White points out the ways in which historians not only make events into stories but into particular types of “plots,” those familiar from fictive writing: Romance, Tragedy, Comedy, and Satire (37). While it may be true that this list is too limited for more general purposes, it is clear that Vladek is making an effort to emplot his Holocaust experience as “Romance,” making it “mean” the happiness and joy of true love that overcomes all obstacles, even when the most significant of those obstacles is the Holocaust. The fact that Vladek’s narration closes here indicates an effort on his part to exert the power of narrative closure over the power of the camps.[9] For White, it is closure that makes narratives “mean,” in that they satisfy the desire (by reader, writer, teller, or listener) to put everything in its place and to fit together. As I discuss throughout this book, narratives are narratives by virtue of their closure, allowing the retrospective gaze that makes sense of all that precedes it.[10]

What makes Vladek’s closure interesting, however, is that it is neither inconclusive (a staple of twentieth-century modernism) nor tidily explanatory (a staple of nineteenth-century realism). Instead, the conclusion is resolutely incongruous. It does provide a tidy conclusion, but it is manifestly unsatisfactory in its efforts to do so. When the reader recalls Vladek’s eyewitness account of prisoners being forced to jump into piles of burning bodies, with the body fat being “scooped and poured again so everyone could burn better” (Maus II 72), his “happy ever after” not only fails to provide an explanation, but highlights its failure to do so. Likewise, earlier in the book, Vladek attempts to control the beginning of his “Romance” by excluding his messy affair with Lucia Greenberg. While Vladek does tell Artie this story, he makes him promise not to include it in Maus (Maus 23). Spiegelman’s inclusion of the episode, in order to make the book “more real—more human” (Maus 23) indicates the degree to which he resists the conventional plot into which Vladek tries to wrestle his experiences (even as it implicates Artie for betraying his father’s trust). While “happy ever after” is a conventional end to a conventional romance plot, the un-edited beginning, when combined with the traumatic middle of Vladek’s tale, and the “future” events recounted in Artie’s competing narrative, renders such a conclusion not only unsatisfactory, but also inaccurate. The fairy tale ending is obviously false.

This romance plot is not, as we have seen, Vladek’s only attempt to make narrative sense of his experiences. At times, he wants to make himself an exemplar of the post-war Jewish/ Israeli narrative of innocence and redemption, a narrative that prevents him from seeing himself in the role of racist, or oppressor, in the incident with the black hitchhiker. He also uses his Holocaust experiences as a means of returning half-eaten groceries and gaining discounts on their replacements, transforming his inexplicable trauma into a way of garnering sympathy from the store manager (Maus II 90). Traumatic and anti-narrative experiences are thus transformed into simple narratives for personal gain. While these narratives may provide momentary comfort, clarity, understanding, or explanation to Vladek, they cannot, in the end, satisfactorily account for or integrate the events of Vladek’s past. While Vladek’s Holocaust experiences are part of an emplotted romance, they also resist their role in that story.

Indeed, Vladek’s Holocaust experiences exemplify Ankersmit’s observation that we should “expect the translation of the world into language to meet with some resistance now and then[.] […] Is it not only at such occasions that we can become aware of reality itself, as possessing autonomy” (Historical 143)? It is clear, in fact, that the reader particularly feels reality’s autonomy when Vladek attempts to transform his survivor’s account into a conventional narrative. Pace White, events, and particularly the Holocaust, do not make sense and this reality shows resistance to the systems of signification applied to it, narrative foremost among them.

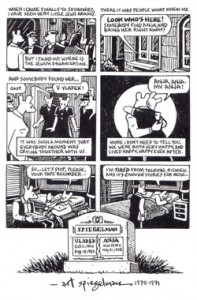

Although several critics note the implicit critique of Vladek’s narrative compulsion in Maus, it is important to see this critique not merely as an attack on Vladek’s personal failings, but on the form of narrative itself insofar as it attempts (and fails to achieve) mimesis. The “happy ever after” panel that concludes Vladek’s narrative is succeeded by several more that conclude Artie’s “present-day” account. Vladek says to Artie: “So…let’s stop, please your tape recorder…I’m tired from talking, Richieu, and it’s enough stories for now” (Maus II 136). Vladek reclines upon his bed, exhausted, and Spiegelman ends the book (outside the narrative) with the drawing of a tombstone with the names of Vladek and Anja, accompanied by their birth and death dates. Finally, Spiegelman’s signature is included, along with the dates of the composition of Maus (1978-1991). While Vladek’s narrative is closed within a version of a conventional “marriage plot,” Artie’s is concluded with another typical version of closure: death. While we do not witness Vladek’s death in the narration, we have witnessed his progressive decline, and the tombstone dates his death to 1982, four years after Spiegelman began work on Maus, but long before its 1991 completion. The deaths of Anja and Vladek are not, however, merely arbitrary endings to a story. Rather, in Maus, they are also metaphors for the end of all stories, or the idea of stories. The last words spoken, “…it’s enough stories for now,” echo Pavel’s “…maybe it’s better not to have any more stories” (Maus II 45).

While the inclusion of a work’s dates of composition is not uncommon, Spiegelman’s juxtaposition of Maus’ with those of his parents’ lives indicates that the telling of the story is itself a kind of death, perhaps of one version of Art Spiegelman, but also of Holocaust “stories” themselves. Vladek mistakenly calls Artie Richieu, the name of Spiegelman’s elder brother, killed by relatives in an attempt to save him from the Nazis (Maus 109). This cements the relationship between the two hinted at earlier, in which Artie discusses his sense of competition with Richieu. “The photo [of Richieu] never threw tantrums or got in any kind of trouble…It was an ideal kid and I was a pain in the ass. I couldn’t compete” (Maus II 15). By calling Artie by his brother’s name, Vladek unconsciously attempts to recall or revive this (idealized) portion of his past that is forever gone. At the same time, however, he declares the close of his narrative impulse, indicating that his efforts at recovering the past through narrative are over and that Artie will never, of course, be Richieu, no matter what stories Vladek (or Artie) may invent.

The inclusion of the two sets of parallel dates also invokes the familiar analogy of writing and death. Both Derrida and Foucault emphasize the “kinship between writing and death,” noting how writing is only necessary if the originator of the story is “absent” or “the writing subject endlessly disappears” (Foucault, “What” 1623). This lack of the author’s “presence” indicates not only death, in poststructuralist thought, but also the impossibility of connecting with the referent. For Derrida, the pharmakon of writing wields “power, over death but also in cahoots with it,” since it allows the author to live after death in representation, but at the same time contributes to the “forgetting” or loss of the “original” (Dissemination 104-105). In the latter sense, the completion of Maus, accompanied by the tombstone and the composition dates, may be read as merely another account of the failure to revive the referent: the Holocaust itself.

In drawing attention to the text as representation, as writing, these dates reiterate the counter-narrative that Maus has kept alive throughout. While Vladek’s account is a narrative of the Holocaust, trying to revive its events and make sense of them, Artie’s “present-day” narrative is always (and increasingly) an account of the failure to do so. If the tombstone and signature combine to be a model of narrative closure, the meaning they convey is a lack of meaning, of the impossibility of Holocaust representation and of the necessity of silence. Artie’s despair is, like Vladek’s romance plot, a narrative that makes sense of his mother’s suicide and his father’s Holocaust experiences. In this case, however, the “meaning” is, ironically, a lack of meaning.

Artie’s account of the failure of language and representation to convey the truth of the past is itself predicated on reading its events as a narrative in which time progresses in a linear fashion from the past to the present and dramatic change occurs that spurs a narrative desire for explanation. It is, after all, only through articulating a rupture that separates present from past that we can begin to say that the past is irretrievable and inaccessible. This rupture, or change, is precisely that which spurs narrative itself, according to such influential models as those of Todorov, Peter Brooks, and D. A. Miller, as discussed in previous chapters. The introduction of this change is that which separates the present telling from past events and which, paradoxically, introduces the impossibility of completely capturing those events, even as they become narratable. From this point-of-view, the present is of a fundamentally different nature from the past, and language, representation, and narrative merely (and futilely) try to bridge the gap that has engendered their necessity. That is, the typical conception of an event like the Holocaust as “impossible to represent” rests, ironically, on its narratability. Its “difference” from those events that precede it is so dramatic that it demands to be narrated. At the same time it introduces problems of representation precisely because of the dramatic rupture between it and the past and future. For Artie, the oxymoronic narrative of meaninglessness or silence becomes necessary.

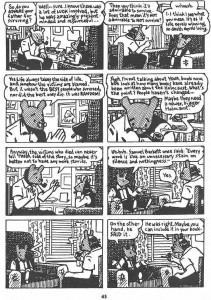

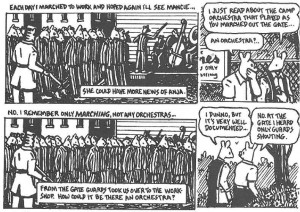

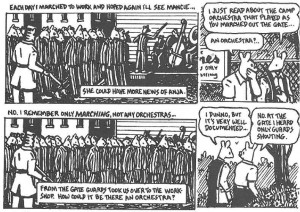

Just as Vladek’s romance plot is contradicted and invalidated by the true events of the Holocaust, however, Artie’s narrative of failure and insufficiency is contradicted by Vladek’s experiences. Even as Artie repeatedly throws up his hands at the impossibility of recapturing history, his transmission of Vladek’s account allows some of history’s truths to “bleed” through its mediation. The narrative of insufficiency is belied by Artie/Spiegelman’s intense preoccupation with rendering the past accurately. In fact, Spiegelman highlights the amount of re-construction in his father’s account not merely to indicate the inevitable distortion involved in any depiction of the past, but also to supplement Vladek’s version of events with more accurate alternatives. Nowhere is this clearer than in the depiction of Vladek’s recollection of his daily departure from the work camp. Artie’s research uncovers that an orchestra “played as [Vladek] marched out the gate,” while Vladek asserts that he remembers “only marching, not any orchestras.” Spiegelman visually depicts the musical instruments anyway (Maus II 54).

Spiegelman is willing to express Vladek’s perspective, but not at the expense of a more fully documented referentiality.[11] James Young comments on how this dual narration, Vladek’s oral and Spiegelman’s visual, allows us a view of “two stories being told simultaneously” (“Holocaust” 676), and how we might read these “two stories” as a competition between a “narrative” strain that tells the story and an “antinarrative” one that “deconstructs” the first (“Holocaust” 673). In this case, however, the deconstruction not only questions the narrative, but gestures towards a greater historical accuracy.

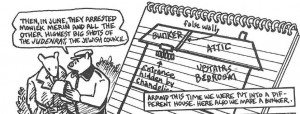

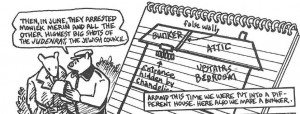

In this, there is some similarity to Rushdie’s use of disnarrated errata. A narrative is provided, but is not the limit of the information given, sacrificing coherence for accuracy in ways that invert White’s complaints about narrative historiography. In an interview, Spiegelman describes this dynamic: “Now my father’s not necessarily a reliable witness, and I never presumed that he was. So, as far as I could corroborate anything he said, I did—which meant, on occasion, talking to friends and to relatives and also doing as much reading as I could” (Brown 93). Similarly, in Maus, Artie asks Pavel, also a survivor, for corroboration of details after Vladek dies (Maus II 47) and includes representations of Vladek’s sketches to clarify oral testimony. Vladek’s sketch of his family’s “bunker” in Srodula, built to avoid capture, fulfills the purpose of Holocaust testimony according to Stern and others: to prevent the event’s repetition. Vladek wants to show Artie “exactly how was it—just in case,” implying that the drawing is not merely a “reality effect” for Artie’s book, but might be needed in case he too has to hide for his life in some nightmare future (Maus 110). While Artie may not be able to present all of the events accurately, the fragments of his account that are true may become lifesavers someday.

If Vladek tries to emplot the Holocaust as Romance, then Artie tries to emplot it with an ironic tropology “in which the author signals in advance a real or feigned disbelief in the truth of his own statements” (White, Metahistory 37). Certainly, the scenes in which Artie expresses the insufficiency of his ability to represent the Holocaust, or Françoise, fall into this category, as do the variety of scenes wherein he discusses the difficulties he is having in writing the second volume. Vladek’s accounts of the camps, however, succeed in making these events present to the reader in ways that belie the claim that the past is irretrievably passed. The mere fact that Vladek’s romance can be invalidated by the brute intractability of the events he describes indicates their autonomy and actuality despite Artie’s construction of a narrative of insufficiency.

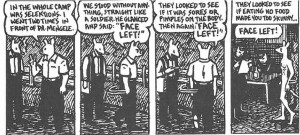

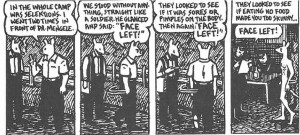

In fact, Maus insistently and visually resists the notion that the past is not present. As various critics have illustrated, Maus continually highlights not only Artie’s frustration at his distance from the past, but also the insistent presence of the past in the narrative present. Erin McGlothlin, for one, details how Vladek is commanded to “Face Left!” by Dr. Mengele in the camps and re-enacts his movements for Artie’s benefit (Maus II 58). The reader sees four panels in a horizontal “strip.” The first three show Vladek demonstrating to Artie in the present, with the fourth showing Vladek in the past being commanded by Mengele. As McGlothlin notes, “This last panel effects a visual break in the block of panels, for it suddenly transports the reader from a visual depiction of a present of verbal narration of the past to a visual depicton of the narrated moment of the past itself” (178). While at first the distinction between past and present seems clear from the visual disjunction between the third and fourth panels, in fact there is more temporal continuity between the four panels than it initially appears. McGlothlin observes that Vladek occupies the same space in the fourth panel as he does in the first three, and the place of the observer, Artie, is replaced by the Nazi, Mengele, who, like Artie, records Vladek’s movements and responses. McGlothlin argues that this establishes a “visual analogue between the original scene of victimization and trauma and the retelling of the event, insisting that the two are not distinct, mutually exclusive processes (179). Beyond this, however, it is possible to see Maus’ resistance to a narrative form that relies on some version of chronology, recounting what is past in the present. Instead, the past is present, not merely in the psychological scars born by both Vladek and Artie, but also in the material body of Vladek. This series of panels insists on our seeing that the same body in the camp “selection” process is the one recounting his story to his son, and as long as that body is present, the past is materially accessible, written upon it.

Indeed, the comics form is inherently suited to such an observation since it is the only medium in which time is both linear and spatial. One must read temporally to progress from panel to panel, but at the same time, a reader can view the pictures in several panels (or in a whole page) simultaneously, allowing her to see both narrative past and narrative present in her own present while reading.[12] Doing so indicates how a model of narrative in which time progresses forward and that separates the past that occurred from the present that explains is unsatisfactory. Here, Spiegelman subverts temporal expectations, by placing the “past” in the far right of the series of panels. In a medium wherein the reader is expected to assume that the panel to the right will take place in the “future” of the panel to its left, this inversion of expectation brings the past momentarily into the future. As Joshua Charlson writes, in Maus “[s]tory is never a smooth, self-contained progression […]; it is interrupted by the present, just as the present is continually assaulted by the past” (107). Maus consistently illustrates the continuity between past and present in this manner, often subtly sliding from Vladek as (present) narrator to Vladek as (past) character with visual cues (McGlothlin 182), allowing the reader to see both past and present simultaneously and experience the relays between them.

Even within the single panel, Spiegelman refuses a simple separation of past events as contrasted with present narration. In particular, when Vladek recounts the hanging of four young girls who were friends of Anja, they are depicted not in their “past” environment in the camps, but as hanging from the trees in the Catskills while Vladek and Artie drive by (Maus II 79). As Rick Iadonisi points out, “temporal seepage” is a crucial element of the text, in which events in past time “bleed” into the present. Most typically, critics see these moments as narratological metalepses and as evidence of the psychological impact of the camps on both Vladek and Artie. At the same time, however, these moments must be read as resisting Artie’s narrative of historical belatedness. While Artie quite frequently expresses despair at the impossibility of recapturing the past, at other times it impresses itself upon the present with such force that it can be seen and heard. Whether it is in the rotating body of Vladek or in the legs of the hanging victims, the material past is embodied in these panels and exceeds the notion of the past as a mere ghost or trace in the shadow of present signification. The poststructuralist narrative in which past experience disappears and is transfigured into non-referential representations is challenged by this version of anti-narrative, wherein the procession from past to present is replaced by a page, and a world, in which the two exist simultaneously.[13]

“A Problem of Taxonomy”

In focusing on the ways in which Vladek’s reliance on narrative ultimately de-forms or distorts the truth of his historical account, Spiegelman may be seen, like Derrida, to be deconstructing the division Nora, Hawlbachs, and others erect between memory and history. If history is a belated instrument that relies upon representation to reconfigure the past, then surely Vladek’s own engagement with the compromised tools of signification indicates how memory may be defined in precisely the same way. Derrida’s claim that the distinction between writing (absence/history) and speech (presence/memory) is “barely perceptible” is particularly apt in this case. To say that the distinction between memory and history is nonexistent is not, however, to merely say that there is no such thing as memory, and that all we have is history, signification, and belatednes. On the contrary, to say the differences between memory and history are imperceptible is to suggest that the attributes typically applied to history must be applied to memory, but also that the attributes typically applied to memory may be applied to history. While the former is the route typically taken by poststructuralist philosophy, this is largely a result of the Cartesianism that Ankersmit challenges.

If, as Derrida asserts, the danger of writing, from Plato’s point-of-view, is that it threatens the interior and the immanent with infection from the outside, then the permeability of external signification with the interior world (of memory/of presence) is established. This merely shows that Plato’s effort to separate speech from writing, and memory from history, is a lost cause, because memory already partakes of the tools of signification. At the same time, if one adopts Ankersmit’s notion of experience impressing itself upon the mind, this permeability works both ways, wherein experience may not only impress itself upon mind/memory, but it may also be transferred to more prosthetic means of representation, like writing, and historical texts. That is, if representation can get in, then surely (past) experience can get out, both into the texts regarded as “documents” for historical research (or first person accounts like those of Vladek) and into the texts that arise from those texts (or third-person historical accounts, like that of Art Spiegelman). (…)

Footnotes

[1] For further discussion of photographs in Maus, see Charlson (109-111), Hirsch, Hatfield, and Elmwood. [back]

[2] The contrast of Maus to more traditional funny animals necessarily rests on the distinction between the Disney capitalist/corporate machine that exploits everything and anything for profit and Spiegelman’s text which either draws the line between profit and “art” somewhere (at Maus vests, for instance), or, at the very least, expresses some guilt about it. Vladek, portrayed as an amoral capitalist in the pre-war years, believes he is giving Artie a compliment when he compares him to the “big-shot cartoonist” Walt Disney (Maus 133), but Artie obviously feels differently. Nevertheless, Spiegelman does articulate parallels between his own mice and those of Disney in the epigraph to Maus II, which quotes a mid-1930’s German newspaper article’s condemnation of Mickey Mouse and Jews, with both linked to debased amoral capitalism. [back]

[3] Bosmajian notes how the desire to have been present at Auschwitz is not atypical for children of survivors. Bosmajian posits that this “insane wish” comes about as a result of the knowledge that the “gap between the experience of the disaster and any mimetic or symbolic construct of it is unbridgeable” (33). [back]

[4] The division of memory and history is undercut by some versions of poststructuralist theory, as discussed in this chapter, and is made even more problematic by Maurice Halbwachs’ notion of “collective memory” which asserts that no memory is individual, but can only be constructed in relationship to those communities to which the individual belongs. While Halbwachs maintains a distinction between history and memory (85-86), the notion that memory is shaped into a communal consciousness implies a distancing between the direct (individual) experience and its remembrance and, in doing so, pushes history and memory closer together. [back]

[5] In History and Memory After Auschwitz, Dominick LaCapra puts the number of Fortunoff testimonies at 3700 and the Survivors of the Shoah Foundation’s at approximately 50,000 (11). In the ten years that have passed since that book’s publication, at least several hundred more have been added to the Fortunoff testimonies and perhaps several thousand to the Survivors of the Shoah. To link either or both of these collections to a true or transparent touching of the past to the present is, as always, problematic, particularly in the case of the latter, funded by Stephen Spielberg and directed with Hollywood logic and production values (Novick, Holocaust 275-76). [back]

[6] Nancy K. Miller makes a similar claim about Maus when she notes that listening to Vladek’s recorded voice at the Maus museum exhibit gives the listener the sense that “the father performs unmediated—to the world” (55). Miller does acknowledge, however, that although the listeners may get the impression of the unmediated, this impression is problematic (59 n13). [back]

[7] Ankersmit distinguishes between the “description” of the past which aims at truthfulness and the “representation” (particularly narrative) of the past that is an argument for how a particular slice of the past is to be defined. Descriptions distinguish between a portion that is referring to reality and a portion that is a property of that referent. So, in “the cat is orange,” the “cat” refers to a real-world object and “is orange” describes one of its properties. Because of the simplicity of the statement, it can be empirically confirmed or denied and is therefore either “true” or “false.” Nevertheless, because of its simplicity, the statement tells us very little about the cat, its origins, its history, its relationships (Narrative, chapters 1-3). Ankersmit concludes that because history aims not only to tell us the factual “truth” of past events, but also to orient us towards them and to help us understand their complexities, this model has little utility. It is possible, of course, to imagine a more radical response to Ankersmit that would focus on how a single word in this description (“orange”) can only be corroborated within agreed social and linguistic boundaries, making such corroboration not a confirmation of the statement’s “objective” truth, but of social/linguistic agreement. While there is little doubt that “facts” depend on what social groups consider factual, it is also true that the discrepancies between such groups are likely to be more limited when treating such a simple declarative statement. Statements of this kind infrequently create the kinds of social and political problems so central to Foucaultian thinking, for instance. The orangeness of cats has rarely been a significant bone of social or political contention. Other, equally short, statements may be much more difficult to extract from their discursive context, however. Freud’s “a child is being beaten” or Spivak’s “white men are saving brown women from brown men” might seem initially to be the kind of factual statement Ankersmit sees as confirmable, but they are embroiled in larger cultural narratives that circulate power. Ankersmit’s broader point, however, is that these larger discourses are precisely that which we should investigate, both because they create more problems for notions of transparent representation and because they have greater educational potential (Historical 39-48). Ankersmit further argues that narratives/representations can be “true” even if some of their individual statements are false (Narrative 58-78). [back]

[8] Interestingly, as the Complete Maus CD-ROM reveals, these lines are not a direct quote from Vladek, but are edited and re-written by Spiegelman. Vladek actually said “finally I found her. The rest I don’t need to tell you, because we both were very happy” (Bosmajian 41). While the “happy ending” of the story is still palpably false, Spiegelman’s addition of “ever after” emphasizes (even provides) the fairy tale feel of Vladek’s conclusion. [back]

[9] For a discussion of the problems of providing closure in any Holocaust narrative, see Levine (70). [back]

[10] There are, interestingly, some examples of critics relying on outcomes to interpret Maus in ways similar to Vladek’s emplotment. In particular, Tabachnick (“Religious”) suggests that Vladek’s survival is somehow meant to happen by God, something proven by various fulfilled prophecies in the text. While there is an emphasis on prediction and fulfillment in these episodes, there is also an emphasis in Maus on the role chance plays in who survived the camps. Pavel asserts, “It wasn’t the best people who survived, nor did the best ones die. It was random!!” (Maus II 45; emphasis in original). Given Pavel’s “wisdom” throughout Maus, it is more likely that we are meant to see the random nature of survival than the fated triumph of Vladek. [back]

[11] For further commentary on the orchestra scene, see Ewert (both sources) and Iadonisi (51-52). [back]

[12] Nearly all comics theorists note this feature unique to the medium. Scott McCloud discusses how comics transform time into space in Understanding Comics. “[I]n comics, the past is more than just memories for the audience and the future is more than just possibilities! Both past and future are real and visible all around us! Wherever your eyes are focused, that’s now. But at the same time your eyes take in the surrounding landscape of the past and future!” (104). The surfeit of exclamation points does not invalidate the claim. [back]

[13] Of course, all of the drawings, regardless of their position on the page are “representations” of the past, not the thing itself, even if they occupy the same diegetic level as the character who purportedly creates them. The blurring of diegetic levels suggests that the past can be made present, but it does not actualize that suggestion unless we are willing to acknowledge that representations can retain some material portion of that which they represent, a possibility I explore in the next section of the chapter. [back]

Works Cited (and some consulted)

Adams, Timothy Dow. Telling Lies in Modern American Autobiography. Chapel Hill: Uof North Carolina P, 2000.

Adorno, Theodor. “Commitment.” The Essential Frankfurt School Reader. Ed. Andrew Arato and Eike Gebhart. Trans. Francis McDonagh. New York: Urizen Books, 1978. 300-18.

___. Negative Dialectics. Trans. E. B. Ashton. New York: Seabury Press, 1973.

Ankersmit, Frank R. Historical Representation. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2001.

___. History and Tropology. Berkeley: U of California P, 1994.

___. Narrative Logic. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1993.

___. Sublime Historical Experience. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2005.

Berlatsky, Eric. “Memory as Forgetting: The Problem of the Postmodern in Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting and Spiegelman’s Maus.” Cultural Critique 55 (Fall 2003): 101-51.

Bosmajian, Hamida. “The Orphaned Voice in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” Considering Maus: Approaches to Art Spiegelman’s ‘Survivor’s Tale’ of the Holocaust. Ed. Deborah Geis. Tuscaloosa, AL: U of Alabama P, 2003. 26-43.

Boyarin, Jonathan. Storm from Paradise: The Politics of Jewish Memory. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1992.

Brooks, Peter. Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1984.

Brown, Joshua. “Of Mice and Memory.” Oral History Review 16.1 (Spring 1988): 91-109.

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1996.

Charlson, Joshua. “Framing the Past: Postmodernism and the Making of Reflective Memory in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” Arizona Quarterly 57.3 (Autumn 2001): 91-120.

Cohen, Arthur. The Tremendum. New York: Crossroad, 1981.

Crapanzano, Vincent. “The Postmodern Crisis: Discourse, Parody, Memory.” Bakhtin in Contexts: Across the Disciplines. Ed. Amy Mandelker. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1995. 137-50.

De Angelis, Richard. “Of Mice and Vermin: Animals as Absent Referent in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” International Journal of Comic Art 7.1 (Spring 2005): 230-49.

De Certeau, Michel. The Writing of History. Trans. Tom Conley. New York: Columbia UP, 1988.

Derrida, Jacques. Dissemination. Trans. Barbara Johnson. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1981.

Doherty. Thomas. “Art Spiegelman’s Maus: Graphic Art and the Holocaust.” American Literature 68.1 (March 1996): 69-84.

Dreifus, Claudia. “Art Spiegelman: The Progessive Interview.” Progressive (November 1989): 34-37.

Elkana, Yehuda. “A Plea for Forgetting.” Ha’aretz 2 March 1988.

Elmwood, Victoria A. “ ‘Happy, Happy Ever After’: The Transformation of Trauma Between the Generations in Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale.” Biography 27.4 (Fall 2004): 691-721.

Ewert, Jeanne C. “Art Spiegelman’s Maus and the Graphic Narrative.” Narrative Across Media: The Languages of Storytelling. Ed. Marie-Laure Ryan. Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska P, 2004. 178-193.

___. Reading Visual Narrative: Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” Narrative 8.1 (January 2000): 87-103.

Fackenheim, Emil. To Mend the World. New York: Schocken Books, 1982.

Finn, Molly. “A Comic Book That Sears Your Heart.” Commonweal 28 February 1992: 23.

Fish, Stanley. Is There A Text in This Class? Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1982.

Fletcher, M. D., ed. Reading Rushdie: Perspectives on the Fiction of Salman Rushdie. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1994.

Forster, E. M. Aspects of the Novel. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1927.

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

___. The History of Sexuality: Volume I: An Introduction. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

___. “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History.” The Foucault Reader. Ed. Paul Rabinow. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984. 76-100.

___. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. 1970. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage, 1973.

___. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings. Ed. Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon, 1980.

___. “What Is An Author?” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: WW Norton & Company, 2001. 1622-36.

Freud, Sigmund. “A Note Upon the Mystic Writing Pad.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923-1925). Trans. James Strachey. London: The Hogarth Press, 1961. 227-32.

Friedlander, Saul, ed. Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the “Final Solution.” Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992.

Gates, David. “The Light Side of Darkness.” Newsweek 22 September 1986: 79.

Geis, Deborah, ed. Considering Maus: Approaches to Art Spiegelman’s ‘Survivor’s Tale’ of the Holocaust. Tuscaloosa, AL: U of Alabama P, 2003.

Gilman, Sander. The Jew’s Body. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Glejzer, Richard. “Maus and the Epistemology of Witness.” Witnessing the Disaster: Essays on Representation and the Holocaust. Eds. Michael Bernard-Donals and Richard Glejzer. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin P, 2003. 125-37.

Gopnick, Adam. “Comics and Catastrophe; The True History of the Cartoon and the Meaning of Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” The New Republic 22 June 1987: 29-33.

Grant, Paul. Review of Maus: A Survivor’s Tale and Brought to Light: A Graphic Docudrama. Race and Class 31 (1989): 99-101.

Grossman, Robert. “Mauschwitz.” The Nation 10 January 1987: 23-24.

Groth, Gary, Kim Thompson, and Joey Cavalieri. “Slaughter on Greene Street: Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly Talk About Raw.” Art Spiegelman: Conversations. Ed. Joseph Witek. Jackson: U of Mississippi P, 2007. 35-67.

Halbwachs, Maurice. The Collective Memory. Trans. Francis J. Ditter, Jr. and Vida Yazdi Ditter. New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1980.

Halkin, Hillel. “Inhuman Comedy.” Commentary 93.2 (Feb 1992): 55-56.

Harvey, Robert C. The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History. Jackson, MS: U Press of Mississippi, 1996.

Hatfield, Charles. Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2005.

Hilberg, Raul. “I Was Not There.” Writing and the Holocaust. Ed. Berel Lang. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1988. 17-25.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory.” Discourse 15.2 (Winter 1992-93): 3-29.

Iadonisi, Rick. “Bleeding History and Owning His [Father’s] Story: Maus and Collaborative Autobiography.” The CEA Critic. 57.1 (Fall 1994): 41-56.

Jenkins, Keith. Why History?: Ethics and Postmodernity. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Jenkins, Keith, ed. The Postmodern History Reader. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Kellner, Hans. “However Imperceptibly: From the Historical to the Sublime.” PMLA 118.3 (May 2003): 591-96.

___. “Introduction: Describing Redescriptions.” A New Philosophy of History. Eds. Frank Ankersmit and Hans Kellner. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995. 1-18.

LaCapra, Dominick. History and Criticism. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1985.

___. History and Memory After Auschwitz. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1998.

___. History in Transit: Experience, Identity, Critical Theory. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 2004.

___. Representing the Holocaust: History, Theory, Trauma. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1994.

___. Writing History, Writing Trauma. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 2001.

Laga, Barry. “Maus, Holocaust, and History: Redrawing the Frame.” Arizona Quarterly 57.1 (Spring 2001): 61-90.

Lane, Christopher. “The Poverty of Context: Historicism and Non-Mimetic Fiction.” PMLA 118.3 (May 2003): 450-69.

Lang, Berel. Holocaust Representation: Art Within the Limits of History and Ethics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2000.

Lang, Berel, ed. Writing and the Holocaust. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1988.

Levine, Michael G. “Necessary Stains: Art Spiegelman’s Maus and the Bleeding of History.” Considering Maus: Approaches to Art Spiegelman’s ‘Survivor’s Tale’ of the Holocaust. Ed. Deborah Geis. Tuscaloosa, AL: U of Alabama P, 2003. 63-104.

Lipstadt, Deborah E. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory. New York: The Free Press, 1993.

Lopate, Phillip. “Resistance to the Holocaust.” Tikkun (May-June 1989): 55-65.

Lyotard, Jean-François. Le Différend. Paris: Minuit, 1983.

___. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1984. 71-82.

___. The Postmodern Explained to Children. London: Turnaround, 1992.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 1993.

McGlothlin, Erin. “No Time Like the Present: Narrative and Time in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” Narrative 11.2 (May 2003): 177-98.

McHale, Brian. Postmodernist Fiction. New York: Methuen, 1987.

Miller, D. A. Narrative and Its Discontents: Problems of Closure in the Traditional Novel. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1981.

Miller, Nancy. “Cartoons of the Self: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Murderer—Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” Considering Maus: Approaches to Art Spiegelman’s ‘Survivor’s Tale’ of the Holocaust. Ed. Deborah Geis. Tuscaloosa, AL: U of Alabama P, 2003. 44-62.

Mordden, Ethan. “Kat and Maus.” The New Yorker 6 April 1992: 90-96.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life.” Untimely Meditations. Ed. Daniel Breazeale. Trans. R. J. Hollingdale. New York: Cambridge UP, 1997. 59-123.

___. “On Truth and Lie In An Extra-Moral Sense.” The Portable Nietzsche. Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: The Viking Press, 1954.

Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 7- 25.

Novick, Peter. The Holocaust in American Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999.

___. That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988.

Orvell, Miles. “Writing Posthistorically: Krazy Kat, Maus, and the Contemporary Fiction Cartoon.” American Literary History 4.1 (Spring 1992): 110-140.

Rothberg, Michael. “‘We Were Talking Jewish’: Art Spiegelman’s Maus as ‘Holocaust’ Production.” Contemporary Literature 35.4 (Winter 1994): 661-687.

Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books, 1993.

___. Orientalism. New York: Random House, 1978.

___. “Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims.” Anatomy of Racism. Ed. David Theo Goldberg. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1990. 210-46.

Seeskin, Kenneth. “Coming to Terms With Failure: A Philosophical Dilemma.” Writing and the Holocaust. Ed. Berel Lang. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1988. 110-121.

Silverblatt, Michael. “The Cultural Relief of Art Spiegelman: A Conversation with Michael Silverblatt.” Art Spiegelman: Conversations. Ed. Joseph Witek. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2007. 126-135.

Spiegel, Gabrielle. The Past As Text: The Theory and Practice of Medieval Historiography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1997.

Spiegelman, Art. Breakdowns. 1977. New York: Pantheon Books, 2008.

___. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. My Father Bleeds History (Mid-1930s to Winter 1944). New York: Pantheon Books, 1986.

___. Maus II: A Survivor’s Tale. And Here My Troubles Began (From Mauschwitz to the Catskills and Beyond). New York: Pantheon Books, 1991.

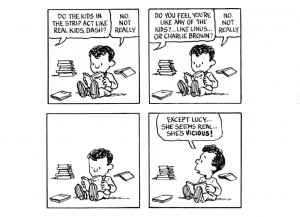

___. “A Problem of Taxonomy.” New York Times Book Review 29 Dec. 1991: 4.

Staub, Michael E. “The Shoah Goes On and On: Remembrance and Representation in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” Melus 20.3 (Fall 1995): 33-46.

Steiner, George. Language and Silence: Essays on Language, Literature, and the Inhuman. New York: Atheneum, 1967.

Stern, Kenneth S. Holocaust Denial. New York: The American Jewish Committee, 1993.

Tabachnick, Stephen E. “Of Maus and Memory: The Structure of Art Spiegelman’s Graphic Novel of the Holocaust.” Word & Image 9.2 (April-June 1993): 154-62.

___. “The Religious Meaning of Art Spiegleman’s Maus.” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 22.4 (Summer 2004): 1-13.

Terdiman, Richard. Present Past: Modernity and the Memory Crisis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1993.

Vidal-Naquet, Pierre. Assassins of Memory: Essays on the Denial of the Holocaust. Trans. Jeffrey Mehlman. New York: Columbia UP, 1992.

Warhol, Robyn. “Neonarrative; or, How to Render the Unnarratable in Realist Fiction and Contemporary Film.” A Companion to Narrative Theory. Eds. James Phelan and Peter J. Rabinowitz. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2005. 220-231.

White, Hayden. “The Abiding Relevance of Croce’s Idea of History.” Journal of Modern History 35 (1965): 102-27.

___. “The Absurdist Moment in Contemporary Literary Theory.” Tropics of Discourse. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. 261-82.

___. “The Burden of History.” Tropics of Discourse. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. 27-50.

___. The Content of the Form. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1987.

___. “The Fictions of Factual Representation.” Tropics of Discourse. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. 121-34.

___. Figural Realism: Studies in the Mimesis Effect. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1999.

___. “Historical Emplotment and the Problem of Truth.” Probing the Limits of Representation. Ed. Saul Friedlander. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992.

___. “The Historical Text as Literary Artifact.” Tropics of Discourse. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. 81-100.

___. “Interpretation in History.” Tropics of Discourse. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. 51-80.

___. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1973.

___. “The Modernist Event.” Figural Realism: Studies in the Mimesis Effect. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1999. 66-86.

___. “New Historicism: A Comment.” The New Historicism. Ed. H. Aram Veeser. New York: Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc., 1989. 293-302.

___. Tropics of Discourse. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1978.

___. “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality.” On Narrative. Ed. W. J. T. Mitchell. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1981. 1-23.

Wiesel, Elie. ‘‘The Holocaust as Literary Inspiration.” Dimensions of the Holocaust. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1977.

Wilkomirski, Benjamin. Fragments: Memoirs of A War-Time Childhood. New York: Schocken Books, 1995.

Wilner, Arlene Fish. “‘Happy, Happy Ever After’: Story and History in Art Spiegelman’s Maus.” Journal of Narrative Technique 27.2 (Spring 1997): 171-89.

Witek, Joseph. Comic Books As History: The Narrative Art of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman, and Harvey Pekar. Jackson, MS: U Press of Mississippi, 1989.

Wyschogrod, Edith. An Ethics of Remembering: History, Heterology, and the Nameless Others. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998.

Young, James. “The Holocaust as Vicarious Past: Art Spiegelman’s Maus and the Afterimages of History.” Critical Inquiry 24.3 (Spring 1998): 666-99.

___. Writing and Rewriting the Holocaust: Narrative and the Consequences of Interpretation. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 1988.

Žižek, Slavoj. “Class Struggle or Postmodernism? Yes Please!” Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left. New York: Verso, 2000.

___. Enjoy Your Symptom!: Jacques Lacan in Hollywood and Out. New York: Routledge, 1992.

___. The Sublime Object of Ideology. New York: Verso, 1989.

Eric Berlatsky is Associate Professor of English at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, Florida. He specializes in twentieth-century British and postcolonial literatures, (post)modernism, and, when he can get away with it, comic books. He has published essays in academic journals or collections on Julian Barnes’ Flaubert’s Parrot, embedded and frame narratives, Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts, Graham Swift’s Waterland, Milan Kundera’s Book of Laughter and Forgetting and Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. He has also published online essays on Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Swamp Thing. He is currently completing work on the editing of a collection of career-spanning interviews with Alan Moore (Alan Moore: Conversations), which will appear in Fall 2011 or Spring 2012 from the University of Mississippi Press. His first book, The Real, the True, and The Told: Postmodern Historical Narrative and the Ethics of Representation is now available from The Ohio State University Press. It includes a lengthy chapter on Art Spiegelman’s Maus, for the comics aficianados.